| |

|

|

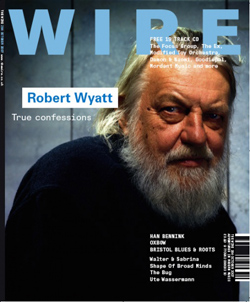

Saturday night and Sunday morning - Wire N° 284 - October 2007 Saturday night and Sunday morning - Wire N° 284 - October 2007

SATURDAY NIGHT AND SUNDAY MORNING

| |

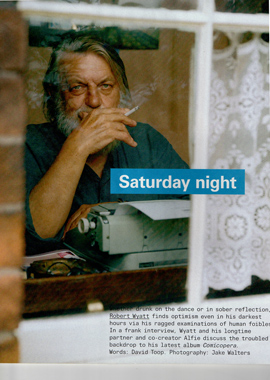

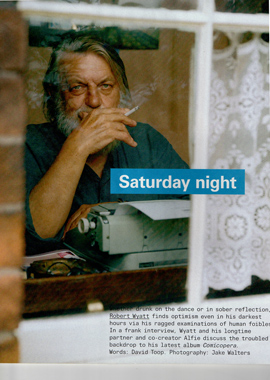

Saturday night

and

Sunday morning

|

|

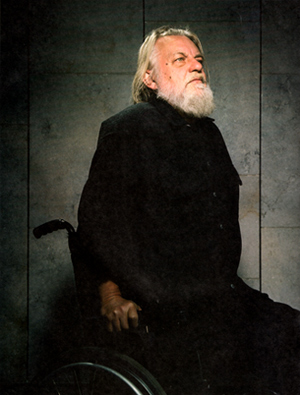

Whether drunk on the dance or in sober reflection, Robert Wyatt finds optimism even in his darkest hours via his ragged examinations of human foibles. In a frank interview, Wyatt and his longtime partner and co-creator Alfie discuss the troubled backdrop to his latest album Comicopera.

Words: David Toop. Photography: Jack Walters.

An abandoned caravan, black inside and empty as a dead tooth, lies wedged into trees on the edge of green Lincolnshire flat lands - main event; figure and ground - and I am on my way to see Old Rottenhat, ranger in the night.

Alfreda Benge, better known as Alfie, has been Robert Wyatt's partner in life, lyrics and artistic production since 1971. She collects me from the nearest railway station to their house in Louth, and during the car ride we talk about mothers haunted by waltzes and away with the fairies in their old age, so touching accidentally on subject matter relevant to songs composed by Alfie and Robert for the new album Comicopera, it's called, which is not indicative of operatic knockabout so much as the stumbling efforts of humanity to be more human. Maybe this jumps too quickly into the work; perhaps better to ask, who is this anomalous person with the convoluted history, with the unique voice, aching, plain and worldly, that can penetrate the emotions not just of greying hippies and Prog rockers but one-time punks, post-punk entryists, soul boys, folkies, improvisors, jazzers, technocrats and many other tribes of music's post-war fallout?

Thanks to bassist Hugh Hopper's Website, with its Soft Machine gig list, I can identify exactly my own first encounters with Wyatt as drummer and vocalist with one of the most enduring, still influential British groups of the late 1960s. There was Christmas On Earth at Olympia in December 1967, where I took photographs of Jimi Hendrix, Pink Floyd, The Graham Bond Organisation and Soft Machine (films long since lost with only one print surviving, a blurred shot of Kevin Ayers in black vest silhouetted against a whiteout of light show); their taped music for Peter Dockley's Spaced event at the Roundhouse; York University and London's King's Theatre, both in 1969, and then the Queen Elizabeth Hall as a quartet with Elton Dean in May 1970.

|

|

|

|

Once Robert was ousted from the group I lost interest, both in the records and the concerts, and like a lot of people, transferred my allegiance to his solo career.

The interest, after all, came from an uneasy but productive balance of contradictory elements: a sweet yearning pop sensibility informed by jazz balladry; the new electronic minimalism of Terry Riley; influences from Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock and other pioneers of extended black music; a very earthy application of the inexplicable doctrine of equivalence known as 'pataphysics. That is to say, a reading of the alphabet or a geographical placement of the BBC tea machine as meaningful as uncountable time signatures and fractured compositional structures.

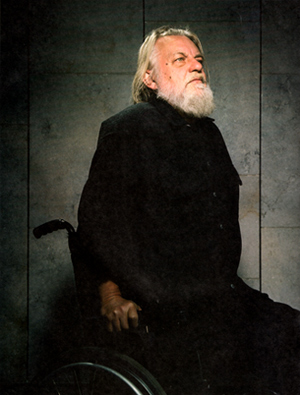

But enough of that, for the moment; I'm in the front door, turning left into Robert's place of work with the piano, the keyboard, the record collection, the antique globe, the photos of Alfie and the LP of music from Syria propped up on the record player, and Robert is looking fitter and younger than he has for many years. In public his persona is customarily gentle and self-deprecating, but at the moment he's twitching with energy, buzzing about the room, beard trimmed, impatient to get on with this ritual we've agreed to enact, and presenting a strong reminder of what an inexhaustible drummer he was before the accident that put him in a wheelchair.

I tell him a story about an academic conference on 20th century music at Sussex University. In 2005 I was invited to give the second of two keynote lectures. The first was given by musicology professor Gianmario Borio of Cremona, who spoke on "Avant-garde As A Plural Concept: Music Around 1968". This is a tricky area, a Saxondale trap for professors of a certain age, radical left politics and progressive music from their youth suddenly assuming a significance that in other circumstances would be taken for twilight nostalgia. After speaking at length about Nono, Kagel and Evangelisti, soixante-huitards and all that, Borio concluded by playing the first few tracks from Soft Machine's Volume Two: "Pataphysical Introduction - Pt 1 " "A Concise British Alphabet - Pt 1 " and a snatch of "Hibou, Anemone And Bear". They begin with this trashy music, he opined, and then abruptly toss it aside in favour of something more challenging. Neat as the metaphor appeared - a suffocating complacency in repressive European society rejected for a more progressive future - I was dubious. Had he been in the audience, would Robert have challenged this dismissal of the pop sensibility in Soft Machine?

"Well, David, to be honest I'm more of a slapper than that," he says, now that I'm asking him. "If somebody likes anything we've done enough to play it in public..."

"You're pathetically grateful?"

"... I'm pathetically grateful. The struggle people had with Gershwin - is he just a posh folk composer or is he a new...? This struggle has been going on for a long time.

"Say a fantastic meal you have, it's not rejecting fried egg sandwiches. Without the basic thing, the apple off the tree or the glass of water, there's nothing to develop. I think Charles Mingus said that if music loses its roots in song and dance it loses all importance or value. I certainly feel that. If music hasn't got song and dance in it, even with a search, it's decorative, but it's deeply trivial. I'm a Darwinist. Song and dance, they're so biologically wired in to what humans do. People have been dancing on a Saturday night for a long time. But there is a Sunday morning, when you have to listen to church music. That's why they invented Saturday and Sunday."

There's a lot of laughing to go with these words, so don't necessarily take them at face value. Robert hasn't become a Christian. He's an unashamed admirer of Richard Dawkins, despite a growing feeling abroad that Dawkins would be Witchfinder General if only the job could be reinstated. "I really envy Christians, and I envy Muslims too, it must be great to be so sure..." he sings on Comicopera's "Be Serious", a strangely cheering gospel shuffle for atheists featuring Paul Weller on guitar. "I've got no one to turn to when I'm sinking in the shit, feel so sad and lonely no one to tell me what to do."

"At the tail end of a digressive response to the Italian professor, Robert turns the argument on its head. "I love pop music to death," he says. "Most great composers rely on folk music. I rely on pop music. I'm not saying I'm a great composer or that pop music is folk music. There's a whole endless thing going on out there. You make your little pond but if your pond isn't connected to the river, which isn't connected to an ocean, it's just going to dry up. It's just a little piss pool, I've lived too long to be happy in a pond."

"This was, more or less, Barbara Ehrenreich's argument in her recent book, Dancing In The Streets: A History Of Collective Joy. "So if we are looking for a common source of depression, on the one hand and the suppression of festivities, on the other," she wrote, "it is not hard to find. Urbanisation and the rise of a competitive, market-based economy favoured a more anxious and isolated sort of person - potentially both prone to depression and distrustful of communal pleasures."

"Wyatt music, by inclination on the slow raggedy side, vulnerability voiced, leaning towards doleful in the reeds and brass, and in its frank examination a questioning of what he calls "human foibles" has more than a touch of chapel and colliery band about it, yet the effect is uplifting, as if we were hearing the more anxious and isolated sort of person transmit a gift of great generosity, optimism and fortitude.

If this makes him Sound too saintly, let's talk about Mingus. When I listen to Robert's music I'm reminded of the sombre beauty of Jazz Composers Workshop records made by Charles Mingus and John LaPorta in 1954-55, or the hushed sadness of Duke Ellington "Mood Indigo". Comicopera shares common ground with the ambitious projects of Carla Bley, Paul Haines, Mike Mantler and Charlie Haden, themselves building on the innovations of Mingus and Ellington. Orchestral suites, song suites, jazz operas, chronotransductions and sort-of-an-operas; all of these terms have been used to describe their method of bringing together distinctive voices, contemporary composition and jazz improvisation as a vehicle for powerful ideas and political commitment.

|

|

Robert sang on Mantler's Many Have No Speech, The School Of Understanding, The Hapless Child, Silence and Hide And Seek, so is steeped in this oeuvre. We begin to talk about what the idea of opera might mean and he tells me a story of being taken to the opera for one of Mozart's earliest attempts at the form. "I was just completely astonished," he says. "It was such a beautiful shock to go into a place where an attempt at archaic things are happening. So that may have interested me. My mother in law, Irena, she had a dog and she used to take this dog for walks. She used to meet other people who had dogs, the way you do. She met somebody's dog and said, 'What's his name?'

"'Amadeus'.

"She said, 'I would call a dog Sebastian; Mozart was so frivolous, Bach was serious', and she went on her way. My mother in law was a Polish refugee

- like refugees must all be burning with a sense of... 'You think I'm an ignorant person to be patronised.

I know stuff you haven't even thought about.'

"I'm not just going round the houses. I just want to establish that when I sing of tragic things, the way it comes out, which is fairly deathly, sometimes I'm not tragedy, I don't do tragedy, I'm not ready for tragedy, I don't understand tragedy. I'm still just a long-winded pop musician. This isn't false modesty. It's just how I see it. But, my songs aren't pop songs. I go on and on for longer than pop songs do. I get bored with hearing the voice so I put in noise stuff, sound stuff. So it's like the voice keeps re-occurring and has to be the main event because I'm a singer, but the songs are not the be-all and end-all of what I'm doing. l'm just trying to string bits of music together."

| |

"I don't know how to mature. I'm constantly being bombarded by images of proper grown-ups and reprimanded by the various headmasters of the world." |

Later he talks about the songs as sketches or caricatures, none of which represents a whole person or any sort of completion. Getting older adds up to an accumulation of loose ends.

Salves, illusions and utopias aside, is there such an entity as a whole person, or any such state as completion or closure? This question makes him quite agitated and defensive. "I don't know how to mature," he says. "I don't know. I'm constantly being bombarded by images of proper grown-ups and constantly being reprimanded by the various headmasters of the world. I don't know enough yet to even have an opinion about anything. I don't now how to argue with that."

Opera is a word meaning work, or labour, as in "do not operate heavy machinery", and this business of musical work is one way in which an isolated and anxious sort of person with no safety net of religion can stay out of the doldrums. Unfortunately, it can also land the same person in the doldrums, decent music being an elusive bastard to pin down.

Alfie enters the room at my request. Since she as so often been at the heart of Robert's work - the subject of one of his finest tracks, "Sea Song" on Rock Bottom, co-author of many compositions, painter of album artworks, a constant presence in photographs, companion, support and shield - I'm surprised she is so rarely asked for her opinion. She laughs, people asking Robert what a song means, what does he know, he didn't even write it.

"You're half of it," he says.

"Well, not half."

So this is the moment to confess that my understanding of words in songs is poor. In general, unless the subject is ostensibly transparent, I have a tenuous grasp, verging on stupidity, of what many singers are on about. Give me the lyrics of an average white guitar band and I'm better off with the sheer surface of a Jeremy Prynne poem. There are songs on Comicopera that seem angry, or disillusioned, perhaps deeply personal, about love or bombs, lost, loss, lossy. Is it me who's lost?

"Words are usually about a few things," Alfie says. "I don't feel satisfied if they're about what they seem to be about. There has to be another possibility. And also people find things in them, which is great. I find things which are there later, and I suddenly realise what I meant, and strange connections. For years I didn't know that "Sea Song" was for me, and Robert thought it was really obvious. I've just written some lyrics for Monica Vasconcelos and they were all about Robert. He didn't know that at all. Then this morning he said, 'You're right, it's all about me.' How music saves you from the doldrums. How it's his lifeline, basically. I thought it was so obvious."

Alfie wrote lyrics for four songs: "Just As You Are", "You You", "AWOL" and "Out Of The Blue". Three of them are grouped together early in the album. Like a mysterious rock in the hallway, they squat in their place, emotional weight, demanding engagement.

"They're all about loss of some sort," she says, "loss of trust, loss of husband, loss of memory. It's about grieving, actually. It's not anger really. We know a lot of widows at the moment. There's a lot of people like Sheila Peel, Helen Walters, Paul Haines's wife, Jo. People who've been part of a partnership, absolutely solid, and their husbands have died. It's really horrible, tragic. So there's thinking about them in "You You "and "AWOL".

"But the other one, "Just As You Are", the one that Robert sings as a duet, it's not exactly disillusionment." She laughs, sighs, looks at Robert.

"Can I say what it's about?"

"Of course," he says. "It's about bereavement during a relationship."

"It seems as if it might be about some kind of unfaithfulness but it's not about that all. It's about one of you..."

"Let's say, for the sake of argument," he says, "the bloke..."

"... deciding it might be rather fun to become an alcoholic, and the other one, who has quite a lot in their life to deal with - a mum whose mind is drifting, lives in a place not surrounded by friends, relies very, very hard on the one thing she married her husband for, which is intelligent conversation, and finds that the only time they ever meet, early evening when they've all done their work, he's downed another little bottle of vodka and says he hasn't. She can tell out of the corner in a microsecond whether he's had a drink or not. Then he becomes totally and utterly boring all evening and then she thinks, God, life is so fucking lonely. You've tricked me. I thought for the last 30 years you would provide me with the one thing that I need in my life - an intelligent pal, and look what you're doing now, you arsehole. There's a lot of anger there. But there may come a day when he's weak and he's stupid no longer and that day seems to have almost come, because he's now for five months..."

"Sober," he says.

"All my anger and rampaging and complaining seems to have worked," she says, "and I've got my old Bertie back."

Rather unfairly, I suggest to Robert that his remark of 20 minutes past, that he is unable to mature as an artist, has just been disproved by this painful revelation of very adult themes: bereavement, alcoholism, loneliness, deception, abandonment and acceptance.

"It's not abstract art," he says, "Abstract art would just be endlessly working out ideas. I'm trying to live through what I do. You do grow older and you do learn stuff, and if you let it, it will get into your music."

One of the advantages of getting older, I venture.

"Yes," he says, "there are several and that's probably the main one. Going back to that Italian bloke you were talking about, it's a useful though and it's exactly the same as my dad's thought, that pop culture is just not enough. Without knowing why, as a youth, I was always looking for an extension, what happens next, where does this go? The explosive moment of excitement, then what? Anticipating adulthood, in that sense. I know it sounds impossibly pretentious but it's just a fact. Being taken to lots of very grown-up concerts as a child, I didn't know why they were going on and on and now I do, because life does."

In the current era of all-ages concerts, pre-18s festivals and pensioner crèches at Glastonbury, the notion of popular music as a teenage moment has become hopelessly muddled.

|

|

"If you want to see youth still wet from the womb in its sylph-like prancingness," he says, "you have to go to ballet or a classical music concert. It's all upside down. I feel, clumsily, just trying to take on the extra equipment I find I need when what started out as a sprint turns into a marathon. So these great weights my parents put on me, of museums and operas, after a few more decades I'm really glad they said to me, 'You must take a woolly and a handkerchief and a change of underwear.' I now know why they did that and I'm grateful. A sprint won't get you through."

That was how I remember you playing the drums, I say, 100 metres dash, stripped to the waist, voice, arms and legs, words and 13/8 or whatever time, simultaneous and full tilt.

"For about two fucking hours," he says, "soaking wet with sweat. Like a lot of jazz it was a combination of aesthetics and athletics. For ten years, more or less every night, I did it like a sprint."

Later, in a moment when Robert has left the room, Alfie joins me, sits down, makes her decision to be absolutely clear.

"I can't do unconditional love," she says. "Robert can." How to accept human frailty when the sprint is over and done? That's the question.

"Some hours later, driving me back to the spot where I pick up my transport to London, she explains in more detail about Robert's drinking, how it came to a head during the making of the album because of his fear that the spirit of the music could only emerge through the spirit of the bottle. The song, "Just As You Are", came about during a session at which the engineer, Jamie Johnson, had come down with a stomach bug. Brian Eno had dropped by, and this is his genius, pushed them both to use time otherwise lost. Write a Country song, he said; play some piano Robert, write a line Alfie. Desperate in the headwind of this oblique strategy, they wrote a song that blew the cover of their central problem. Since then, Robert has been going to Alcoholics Anonymous, and perhaps as a consequence of his new sobriety, looks about as fit and strong as I have ever seen him.

But the subject troubles me, generates feelings of disloyalty, is the gist of what I say.

To speak about such secrets in public, making hidden addictions common property, can transform them into tangible, negotiable conditions, is the gist of what she says.

Certain relationships are described in terms of records, I notice. When Robert and Alfie met, at the beginning of the 1970s, he was impressed by her record collection: John Coltrane, Sly And The Family Stone, alto saxophonist John Handy's Recorded Live At The Monterey Jazz Festival. Later, he talks about his current listening habits, which have moved back into the 1940s, to Ellington, Glenn Miller even, and Eddie Haywood, the pianist who accompanied Billie Holiday.

"I seem to be going back to the 40s in tandem with Alfie," he says, "who has become terrifically interested in finding photographs of her middle European ancestors. She's got extraordinary roots in Slovenia, Roland, Trieste, Austria. She spent the first seven years being carted around Europe by her mother before being brought to England in 1947. I've been doing a strange parallel thing.

"I was born at the end of the war. My dad had Vera Lynn records - they were some of the few pop records that he allowed that had an importance that transcended what he considered their merit, as a trained musician that he aspired to having been. Professionally he was a psychologist, but as a young man in the 1930s he'd been a pianist and had in fact made a few 78s accompanying some Italian tenor, playing a few arias. He played Debussy and Ravel, though only on record by the time I knew him. I didn't meet him until I was six and within two or three years he developed multiple sclerosis and couldn't read music any more, hadn't learnt any and couldn't improvise. He was with his first family until I was about six and he didn't join my mother until I was about six. He left his first family behind and joined his second one. I have no idea what that was about, really. He was married to somebody else when I was born. By the time I knew him the only things he could play by memory were folk tunes and Christmas songs, so he'd play "Little Brown Jug Don't I Love Thee" and "Away In A Manger" and at Christmas I would sing those with him. That's what I remember."

There's an uncomfortable parallel here: two men, father and son, prevented by disability from pursuing their music, except for the fact that Robert has taken that initial loss as a form of liberation, rebuilding it into music that is deeply personal yet speaks to listeners of all generations, all proclivities, all allegiances. Just run through a partial list of collaborators: Jimi Hendrix, members of Pink Floyd, Scritti Politti, Mongezi Feza, Ivor Cutler, Elvis Costello, Paul Weller, The Raincoats, Evan Parker, Ultramarine, Mike Mantler, Björk, Anja Garbarek, Brian Eno. Just his minimal piano part on Brian Eno's Music For Airports has launched a thousand Ambient, post-Ambient, television and movie soundtracks.

"I never thought I'd be a musician when I was a teenager," he says. "I tried to learn a couple of instruments when I was younger - violin and trumpet - but couldn't read music and left school in disgrace when I was 16."

What did you hope to be?

"A painter, an artist," he says. "I thought it'd be great if you had a tube of toothpaste the size of a lamppost all bent on a lawn with stuff like squeezed toothpaste coming down the side. Eventually pop artists did that so I thought, there you go, I'll be a conceptual artist. René Magritte had a composer brother who never bothered to compose anything at all and I thought that was so fucking Zen. So this was my idea of being a truly conceptual artist. I think it may be why I got on so well with Brian Eno later on. We'd Just sit around thinking of things that could be done. I'm not a great believer in individualism. I think things are around to be done and if one person doesn't do it another will."

You like your songs to sound unfinished, I say, a bit rough round the edges, a bit abrasive in the mix, like everybody is in the room, air stiff with fags, the playing is in the moment, and what is left suspended after the event can take its Darwinian chances out in the world.

"I got that a lot from painting," he says. "From the late 19th century, painters stopped finishing things off. Before photographs, the ideal painter finished. I Just grew up with post-Cezanne artwork where the brushstrokes are fairly scruffy. As long as you got the structure right."

You like a thick sound, I say, a kind of wheezing, wall to wall, portative organ meets harmonium earth to sky privet hedge seething with bees.

"That's Cezanne as well," he says. "A lot of it comes from painters. In Cezanne you don't have many clear horizons or skies. It's texture to all four edges. It's like looking at a text, or something; you're not going to get a landscape or even a person out of it. You've just got this dense, arbitrarily hacked-out oblong of texture. It's taken to its extremes on Comicopera - the semi-instrumental - "Anachronist" - it's floor to ceiling stuff. I like Cezanne, I like Vuillard. That's what I like.

"It's difficult if you're a singer because singers make very clear landscapes, the backing, the ground and the sky, then the voice is a person in it and maybe the other instruments are the trees in this landscape. I always feel that an awful lot of music has done that - you've got the bedrock and then you've got these people standing up in it - the voice and the soloist. I just got used to the idea of an almost underwater thing, of great swirling mixtures without a horizon, without a top or a bottom, just a great churning mix of stuff. I would do that a lot more than I actually do, but being a singer I feel obliged to identify the singer and say yeah, hands up, I'm the singer. Otherwise how could I put 'Robert Wyatt' on front of the record? Otherwise ideally I'd just disappear in with the mesh."

He moves into the hallway, by the front door, where a reproduction of Samuel Palmer's astonishing brown ink and sepia drawing, Early Morning, is fixed to the wall. Teeming with life, picked out with microscopic details, full to the edges with mystic intensity, it portrays a woodland as seen by a travelling knight, "When that misty vapour was agone and cleare and faire was the morning". In the foreground quivers a rabbit, fixed as the fallen log, and at a central point to which the eye is drawn, almost hidden in the shade of a mushrooming oak tree, sits a group of four people, perhaps praying.

"In a painting," Robert says, back to me and looking into the image, "if there is a person in it you scan it in a much more detailed way. There's this drawing out here, Samuel Palmer. It's extraordinary for the era, 1825, way before the impressionists. There's a little huddle in the middle. There's no question that for a human being looking at the painting that huddle becomes the main event. Next is the rabbit. There is no objective animal that can look at that. Presumably if you were a member of the tree race, the thing you would notice is that log down there and think, that's awful, like a dismembered arm.

"The equivalent of that is hearing a voice on a record. You cannot help but pick it out and to the extent you get into the record what that voice is doing and to the extent that you can recognise it as a fellow human and what it's asking of you. There's no avoiding that. On this record most of the time I've stuck the voice fairly up front. I listened to a lot of Johnny Cash, thinking, yeah, better or worse, that is how people communicate with the voice. You are not Mozart after all, old son."

This leads to a conversation about Palmer and William Blake (and I'd add writer John Cowper Powys), in which Robert talks about the romantic local sensibility of Britain. "You don't have to go to Italy for romance," he says. "It was here all along. I feel really in tune with that." The subject of folk music has emerged at various points during the day, with Robert and I both admitting our struggles and changing attitudes regarding English folk. In the 1960s, like me, he rejected most of it, James Brown's brand new bag being far more immediate. James Brown is still up there, but for the rest of it, now he's not so sure. I ask if he and Alfie had heard Rachel Unthank & The Winterset's new album, The Bairns, with its deeply moving version of Robert's "Sea Song"? The room explodes for a moment, yes and yes, Robert in wonderment that she has captured the core of his song so completely.

The ghost of James Brown having entered the room, I mention a concert I watched on television earlier this year, one of Brown's last performances before his death. I was puzzled by his frequent mentions of Wes Montgomery, who probably meant nothing to the audience. "I'm so glad about that" Robert says, "because Wes Montgomery is someone I'd been listening to on my own. That's when you know you really like music, when you don't expect anybody else to be interested." We listen to a track from one of Robert's recent acquisitions, Montgomery playing "Twisted Blues", live in Belgium, 1965, the drive and economy of the solo making both of us realise why this guitarist who looked like a middleweight boxer meant so much to James Brown. A little bit later we listen to a record of alto saxophonist Charles McPherson, with strings. I'd like to hear you record an album with string, I say, like Ray Charles, "Lucky Old Sun", Chet Baker, "Grey December", Charlie Parker, "Just Friends". He laughs, tells me certain people ask him why he can't just make easy music.

We've been talking for quite a few hours. Are you tired of this, bored, fed up?

"No, I'm all right," he says. "I've just run out of fags."

Comicopera is released this month on Domino. Robert Wyatt will appear in conversation at London Purcell Rooms on 15 October: see Out There.

|