| |

|

|

The

freewheelin' Robert Wyatt - Uncut N° 125 - October 2007 The

freewheelin' Robert Wyatt - Uncut N° 125 - October 2007

|

|

INTERVIEW by JOHN MULVEY

PHOTOGRAPHS by DEAN CHALKLEY |

Robert

Wyatt's home is in the centre of Louth,

a quiet town in

the Lincolnshire, hinterlands. A swift, wheelchair ride

down the road from his house, there's the Co-Op where Robert

was shopping when the first of the summer's floods arrived.

Nearer still, there's the market square where he goes for

sausage sandwiches a few lunchtimes a week. "Tea 40p.

Not bad, is it?" he notes approvingly.

It's a strange place to find a man like Robert Wyatt. He

has, after all, followed an idiosyncratic and cosmopolitan

musical path for over 40 years, with Soft Machine, Matching

Mole and on his own rare and lovely solo records. He has

consorted with musical legends - from Hendrix, Moon and

Syd to Weller, Eno and Phil Manzanera. He has been steadfastly

radical in his politics, and global in his outlook. By the

end of his new album Comicopera, in fact, Wyatt is so disgusted

with the behaviour of the British and American governments,

he abandons his mother tongue and sings in Italian and Spanish

instead.

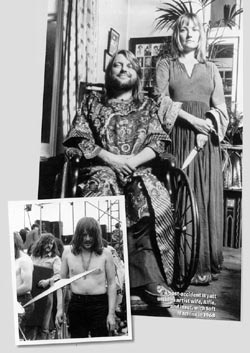

For such a committed internationalist, you'd imagine Lincolnshire

would be a little too parochial and conservative. But Wyatt

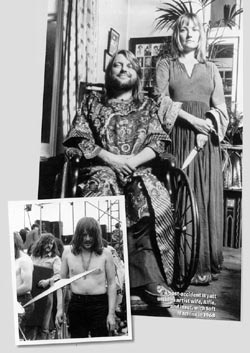

and his wife, Alfie Benge, have lived in Louth for some

two decades. This is where Alfie, an artist, found a house

that they could afford and which was big enough to accommodate

her husband - wheelchair-bound since he fell out of a window

in 1973- on the ground floor.

Robert's lair is the front room, just past the step with

" R A A"

drawn into the cement and the door decorated with a photograph

of Picasso. Here, he plays Gil Evans albums, makes tea,

smokes endlessly and records his impressionistic, entrancing

songs. Here, too, he welcomes us for a leisurely amble through

an extraordinary career.

"I have no agenda, as they say on Big Brother,"he says, arranging cigarettes, two pouches of tobacco, papers,

matches and lighter on the table in front of him. "Gameplan?

Me? No, I'm just here for the crack, man."

Do you watch Big Brother, then?

Alfie watches it, I see it. I can't believe how rude people

are to each other. Andy Warhol would absolutely love it.

Did you ever meet Warhol?

No, although I met Warhol's associates in 1967 when we [ Soft

Machine] were playing in the south of France, adjacent

to a German beer festival, basically living on the beach...

Grey, actually. People always think beaches are pinky orange,

but this was grey with dirt. Or was it pine needles? I don't

remember. Rubbish for sex, actually.

Anyway, yeah, we were doing music for a play: written by

Picasso, I think. And among the people involved were Factory

stars and starlets. They were very nice, very funny.

There were few people you didn't meet...

Well, I haven't gone out of my way to meet people. It's

because I've been at it a long time now. I'm in my sixties

and my first paid job as a drummer was in 1963, so it's

been getting on for 35 years, hasn't it?

Forty-four.

Is it really? For the first 10 years I was going round drumming,

and it's a social activity. Drumming is like being the engine

of a car. Somebody else has to be the car.

Your parents seemed to be quite bohemian, being friends

with the poet Robert Graves and all. What was your childhood

like?

My dad was an industrial psychologist, my mum was a journalist,

and it was a fairly straight upbringing. We just had a lot

of nice artbooks around the house. I struggled through grammar

school, which I absolutely hated. I got caned a lot when

I was at school. I think that's what put me off.

Why were you caned?

We lived near Canterbury Cathedral, we used to sing there

and once, in a casual moment of hubris, I wrote "Jesus

Christ" in a visitor's book. I was caned for that.

Then, when we got to the fifth form, the headmaster gave

us boaters, because he fancied we were a public school.

I steamed mine up into a sort of cowboy hat, and I was caned

for letting the school image down. Blimey, my bum was sore

by the end of all that.

|

|

All the way through Soft Machine

you seem to have been a bit of a troublemaker, as well.

I was always getting into trouble, but I'm not sure that's

the same thing. I was never a born rebel. I think there's

something utterly meaningless about that, it's totally posey.

I liked my parents, I tried to fit in. Half my recording

is an attempt to make normal records, seriously, but what

I do just doesn't come out normal. That's not deliberate

troublemaking.

When I joined the Communist Party, someone said, "Don't

you mind being told what to do?" and I said,"No,

not at all."

I thought that the band [Soft Machine] was being

taken in a direction to compete with American jazz rock

and I couldn't or didn't want to do that. I remember the

organist [Mike Ratledge] once said to me, "Why

don't you learn to read music?" and I answered, "So

that you can't tell me what to play." That was probably

the nail in my coffin as far as that band was concerned.

What about the drinking? Weren't you on a slightly different

social path to the other Softs?

Well we all know that young drunken men are a terrible pain,

and the others didn't really drink. They weren't always

kind, but they were well-behaved, and I wasn't.

Didn't you end up spending time in Laurel Canyon with

Hendrix at the end of the second Hendrix/Soft Machine American

tour?

That's true. The whole of'68, we were there with the Experience,

and at the end of it, our group broke up, basically. I hung

on because Noel and Mitch and Hendrix said, "We've

got this place and there's a spare room if you want to stay."

I'd hung out more with them than with the members of the

band I was in, as they were all drinkers like me.

Listening to Hendrix play every night, he was absolutely

wonderful, and I knew it then.

What he did was just eyewateringly magical. He would transform

hotel rooms into magic little rooms, turn them into some

curious little temple of a hitherto unknown sect. He was

very shy and polite; courteous to a Victorian extreme.

Did you do drugs with him?

I didn't take drugs, no, I just drank. Since you can get

completely out of your brain on legal drugs, why bring the

law into it?

More proof that you're not a rebel, I guess.

I don't like breaking the law; it embarrasses me. The idea

of hanging round policemen is dull.

So you never took acid?

I don't think so. I think I took some substitute - was it

TCP? No, that's what you cure cuts with. Knowing me, I probably

did take TCP! I didn't like it at all. I associate certain

conversations with rooms full of drugs, like [adopts

whiney American voice], "What sign are you?"

and "Do you like The Doors?" And the record would

be The Grateful Dead, always. Was it always the same record?

Who could tell? I got claustrophobia in that atmosphere.

The thing I didn't understand about white American rock

was that they were loud folk bands, whereas the English

scene was much blacker. Even before rock'n'roll, the tradjazz

musicians had this fantasy New Orleans they took around

in their heads. The modernists had an imaginary Harlem -

which I still have.

You recorded with Syd Barrett...

Well he asked us. We were two bands [Soft Machine and

The Pink Floyd] that played in the same places and who

weren't playing "In The Midnight Hour" because

neither of us could play it very well, probably. I liked

working with people from the Floyd, because they were so

different from us. We would play 100 notes, as many as possible,

and they would play as few as possible. I was fascinated

by that, and I was very pleased to go and do [Barrett's

first solo LP] The Madcap Laughs. It's a lovely record.

What was he like at the time?

I didn't know he was meant to be mad or disturbed or anything.

He just seemed very well brought-up and polite. Jolly good

songs, that's all I knew.

Did you play the UFO Club a lot with the Floyd?

We did. I remember the dressing room at UFO was very small,

with benches either side. The Pink Floyd had incredibly

long legs, so their legs would come across and cross each

other in the middle, like the giant scissors they did in

The Wall. They were very kind to us. We had crap

equipment that tended to blow up, they had good equipment

- they were never poor - and they would let us use their

gear - actually quite unusual in those days.

What about Keith Moon? You drank with him?

He took me down the blissful road to hell, several steps

at once. Hendrix and I used to go down to the Scene Club

in New York, and there would be Keith at the bar. His arm

would go around your neck and say,"What are you drinking?

Look, try this Southern Comfort." I'd go,"It's

a bit sweet." He'd say,"Yes it is, so what you

need now is a tequila." We'd do it with the salt and

lemon. I'd say,"Oh, that's a bit salty. "He'd

say, "Yes it is, so what you now need is another shot

of Southern Comfort." He taught me how to get completely

blasted very quickly, so within 40 minutes you were on another

planet. Thanks, Keith, I enjoyed it, but it probably wasn't

good for me in the long run, and it certainly wasn't good

for you, old son.

Was that what you were drinking the night of your accident

in l973?

What I remember is mostly punch - what on earth is that'?

- but Kevin [Ayers], I think, brought out a bottle

of scotch whisky, and then I felt like I was flying out

of the window. Turned out I was [laughs]. That's

all I remember.

Did that stop you drinking?

No. The first time I got out of hospital, Alfie wheeled

me off to the pub. We were really broke - we had about £15,

and then the Pink Floyd did a benefit for us for a few thousand.

We'd just heard about it and it was fantastic for us. So

we went out and got drunk, and when we got back in,

Alfie was reprimanded for being drunk in charge of a wheelchair.

No, it didn't stop me at all. We both used to drink a lot,

me and Alfie.

|

|

When did you calm down?

About two months ago. I finished this record and then I

stopped. I've had about six relapses, which sounds like

a lot, but it's fantastic for me. I tried to write a tune

the other day, and I can't remember writing a tune sober

ever before. I couldn't imagine normally even sitting down

at a keyboard Without the bottle of wine on the left hand

side and the packet of fags on the right hand side.

Did you have a drink problem all that time?

It seems like I had, yeah. Answering the questionnaire for

alcoholics, it turns out I'm one of the unlucky ones who's

an alcoholic, so I can't drink

moderately or anything. We'll see how it goes.

It's incredible that, looking through 40 years of photos,

you're smoking in nearly all of them.

People ask how many I smoke and I say, "As many as

possible." If there was a mile-long cigarette that

I could have suspended in front of my mouth, it would go

straight into my mouth in the morning and come out at night

before I go to sleep.

It's interesting that Rock Bottom [Wyatt's second,

greatest solo LP, from'74] was partially written before

the accident, because it's so often stereotyped as your

post-traumatic record.

It's a funny thing, I always feel embarrassed to say this,

but I don't mind being in a wheelchair. There are aspects

of it that I find quite novel and entertaining. I didn't

see it as a record about a tragic trauma. It's actually

quite euphoric, to me it's more like the phoenix out of

the ashes. Having the nerve to play my own keyboards, having

played with all those brilliant keyboards players - trying

to get away with it was exciting.

I think Rock Bottom is about the possibilities of love:

what someone who loves you will do, and the gratitude that

comes in response.

That's much more I like it. I'd been with Alfie a couple

of years, and I'd been quite rotten to her while I was in

hospital. Me and Alfie had already been married before,

we'd had about three decades each of bipedal life. I say

it was all right for me, but a lot of people come out of

hospital and it's not all right at all. I had Alfie, and

Alfie with her friends really helped. I felt like life was

making more sense afterwards than it had done before. I

was actually very unhappy through the'60s. Being thrown

out of Soft Machine, the damage it did to my confidence

was far greater than the physical damage of breaking my

back. It was like being washed up on a really nice desert

island from a ship that had come from a port in a grubby

cold northern town. It's terrible but it's not that terrible

[Laughs]. Alfie has suggested that I'm much sadder

and more traumatised than I allow myself to think. I don't

know. How can I know if I'm kidding myself?

You seem to flourish as a collaborator with friends,

but not as a bandmember.

That's exactly right. The trouble with a band is I can't

take orders and I can't give orders. The people I choose

vary enormously because it's not for the instrument they

play or their style but what kind of company they are. With

the final record I believe in a sort of benign dictatorship.

I will edit ruthlessly'til every thing sounds good to me,

simple as that, 'cos my name's on the cover.

With the last three records [Shleep, Cuckooland and Comicopera]

I found my imaginary band. It's a lovely band because it's

not any band that could exist in real life on the road or

any thing like that. It's a basic team; there's Annie Whitehead

[trombone], Yaron Stavi on bass, Gilad [Atzmon,

saxophone], that's the core. Then people like Phil Manzanera,

Eno and Paul Weller do cameo roles. It's like a little musical

family.

There's something incredibly English about your music,

even when you sing in Italian or Spanish...

I am totally English. I love the lyrics of Noel Coward,

I even like Gilbert & Sullivan. But the point I would

make, to the BNP and people who go on about their culture

being threatened by alien things, is that no one has allowed

and welcomed non-English cultures so wholeheartedly into

their lives and into their brains and into their food more

than I have. Yet I don't feel the slightest bit compromised

or diluted as a human being. I'm as English as my Staffordshire

great-grandparents. As my Lancashire dad would say, what

the fuck are you all scared of? What kind of wimps are you

that if the man standing behind you in the checkout queue

is wearing a turban, how does that threaten your identity,

you twats? Get over it, for fuck's sake.

On Comicopera, there's a song

called "Something Unbelievable" where you voice

the anger of a bombed Palestinian. The last lyric is,

"You have planted an everlasting hatred in my heart,"

and after that you refuse to sing in English for the rest

of the album. Why is that?

Susan Sontag said that people can moralise in politics,

but in the end morals in politics are about empathising

with the other. Instinctively, that's what I've always

done. It's to do with a craving - it's not so much a principled

stance, it's much more primitive than that - for cultural

biodiversity, and a fear of cultural incest.

During my

lifetime, the English-speaking people have bombed about

25 countries. It seemed to me legitimate that anyone who

had been bombed like that might be feeling that they're

going to hate the bombers for the rest of their lives.

The children and the families of your victims will rise

up, and they won't like you. I wanted to disassociate

myself from the English-speaking trajectory abroad.

The middle chunk of this record is England, and it's not

all bad. There's nice tunes, a good laugh, scepticism

and grumbling. But at the end I think, 'Oh fuck, I'm off',

and the last chunk is all about different ways of getting

away from the mainstream, whether it's the avant garde

or singing in a foreign language or singing surrealist

songs.

It seems very odd that you should end up in a county

as conservative as Lincolnshire.

Henry VIII called it this "brute and beastly shire",

hanged a few recalcitrant Catholics and went back home.

He's not entirely wrong, but he's not entirely right.

There's a village up the road where they're saying,"We

don't need any Kosovans here," and I'm looking at

the women thinking, "Yes, you do!"

I miss London life, the cosmopolitan thing, and we do

go back there several times a year. It's a local joke

that life is cheap in Lincolnshire, and we can have a

house here for the price of a flat in the south. I can

make all the racket I like and no one's going to bother

about it. I can get everything I want just around the

corner, it's like the imaginary community in a child's train set.

Everyone here seems to know you.

Well, I like buzzing about town, it takes me away from

the prison of the keyboard. I'm just one of the local

derelicts.

Comicopera is released on October 8 on Domino

|