| |

|

|

Lost

and Found - Plan B N°26 - October 2007 Lost

and Found - Plan B N°26 - October 2007

LOST AND FOUND

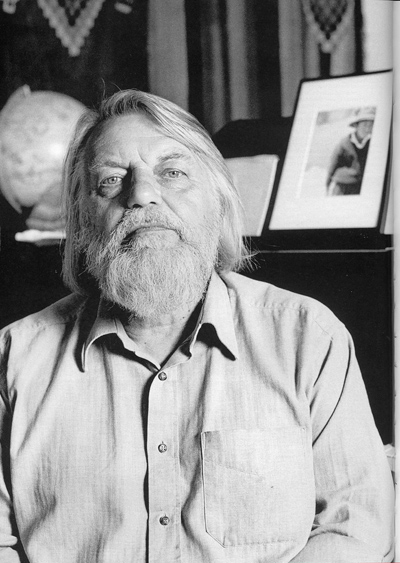

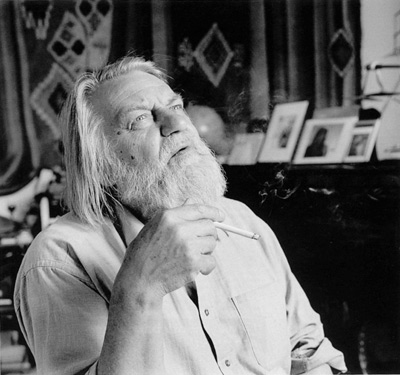

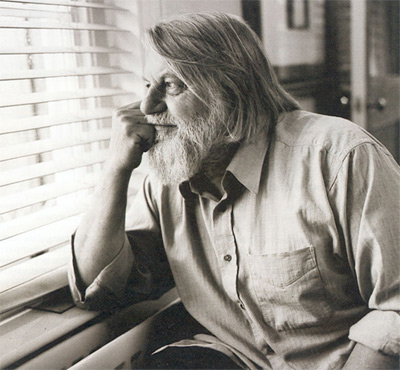

Words Frances Morgan

Photography Simon Fernandez

" For better or for worse, when you put on one of

my records, you're getting me, " says Robert Wyatt.

Plan B was only too happy to spend an afternoon

in the company of the reluctantly iconic songwriter -

and his bewilderingly beautiful new album, Comicopera

|

|

"About 10 minutes ago I said,

you've probably got some questions," says Robert Wyatt.

"And then I kept talking. Look, go through your questions.

Eat. Eat and drink and smoke, "he urges, proffering

a light and some cake. "Otherwise, life, you know,

just dries up..."

I'm fine with the latter three. Cup of tea,

Drum Mild, a Danish pastry with custard in it. I'm fine

sitting in a light front room full of stuff - instruments,

records, pictures - and talking about Cecil Taylor and William

Parker. Maybe we could just do that. I could do that all

day, probably. It's what I do a lot anyway. Talk, smoke,

listen, talk some more; the outside world driving around

doing whatever it is it does on the other side of the curtains.

But the room I'm in belongs to Robert Wyatt, and I'm here

to talk to him about his new album, Comicopera. I've

travelled to Louth, in Lincolnshire, by train and replacement

bus and a drive through big-skied cloud-blown countryside

with Wyatt's wife, artist and writer Alfreda Benge, who

says right away she's glad that photographer Simon Fernandez

and I are smokers. This is a relief to me too because, throughout

the journey, I've veered between making conscientious, illegible

notes, gazing camera-eyed at an unfamiliar part of England,

and getting nervous to the point of missing I'd wished the

train this morning, and I could do with a fag. I don't think

the weight of expectation has ever sat upon my head with

quite such ominous heft as it has today.

Of course, the expectation budges as soon as I'm welcomed

into Wyatt's room, greeted with an enormous smile and the

offer of a cuppa from an instantly recognisable voice -

a voice that, when singing, seems full of quiet concern

for or knowledge of its listeners.

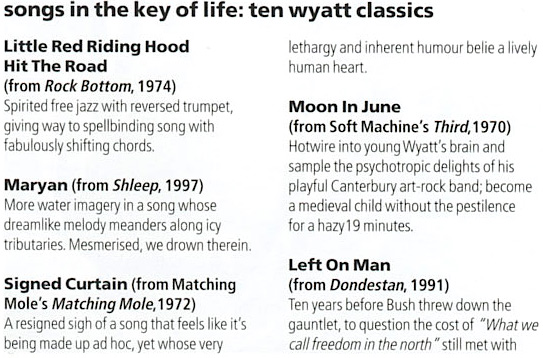

To be honest, that weight of expectation dissipates whenever

I actually hear Wyatt's music, which is why I'm here in

the first place. From the playful art rock of his early

bands Soft Machine and Matching Mole, through 1974's revelatory,

harrowing solo album Rock Bottom and the early Eighties

singles that further defined his sweet, weird, drifting,

impressionistic, committed and heartfelt free-pop, to the

meditative and eclectic Shleep of 1997, and beyond,

Robert's Wyatt's music asks a lot of the listener, but does

not demand. Rather, it suggests, via dreamlike timbres,

open chords, gentle percussion and an almost unbearable

emotional honesty, nothing less than the map of a human

spirit, sketched out in sound. But what that means is, it's

music that means so much to so many people, in a quiet private

way that they hold close to themselves. I'm one of those

people, too, so I don't want to let us down.

So I gesture at my notes.

Yeah, I wrote some questions. I find asking them quite difficult.

"Just give it a go. I'm on your side, do you know what

I mean ? It's your gig now. I've done my gig, I've made my

fucking record."

All right, we'll talk about the record to start with.

Tell me some stuff.

"Playing it back I realised that I do play very loud

cymbals all the time..." Wyatt reflects, referring

to the ripply, brittle scatters of cymbal that have punctuated

his percussion since his early days as a jazz drummer "I

won't abandon what I do just to be fashionable, so I keep

going 'Tssh! Tssh ! Tssh !'. I feel a bit embarrassed sometimes

that I'm drowning out all these wonderful musicians with

my splashy cymbal noises."

That wasn't the first thing I would have noticed about

the album.

"Thank you. But I just listen to it and get so embarrassed.

It's like old people who get hairs growing out of their

faces in weird places and you're having a conversation with

them and thinking, 'Fucking hell, he's got a black hair

growing out of his nose'... But no, it's just weird stuff," he laughs, describing the record's mood, or possibly

his own on listening to it: "'I'm lost, I'm somewhere.

But wherever that is, that's here'. The first track does

it on this record. Thank you, Anja Garbarek, for writing

it."

Comicopera's opener, 'Stay Tuned', is a slowburning,

beautifully simple tilt between uncertainty and surety.

The questioning verses - "In between, lost in noise,

somewhere, somewhere, somewhere" - settle into

encouragement and resolution, steady bass bolstered by trombone

and trumpet: "Don't start searching, I'll get back

to you."

You mean that state of not really being sure where you

are, but being OK with that?

"Yeah, thank you for saying that. You've pinned it

down exactly."

That sense of drift in your music is one of the things

I like most about it.

"My physical response to what I'm doing is... Once

I start making noise it's a bit like jumping into water

and sometimes I'm in a pond, which I would call a pop song,

and sometimes I think, 'Oh fucking hell, this isn't a pond,

this is the ocean'. I'm somewhere bigger than a pond, and

it gets a bit more scary."

Is that something that you can't really plan?

"You cannot plan it. If you do, you're being a cynical

media bastard and it will always show up."

SIGNPOSTS TO SOMEWHERE

In a roundabout way, this is how we talk about Comicopera,

an album that's both immediate and a bit unfathomable, like

all Wyatt's records. It is an album in three discrete parts,

'acts', but I'd argue you could listen to it without knowing

that. You would, however, notice how it deepens and changes:

locationally, from domestic/internal to a confusing but

familiar outside, to - suddenly and devastatingly - a world

beset by conflict and chaos and thence back inside again

into a rich, almost desperate imagination. Sonically, you'll

hear the familiar washes of plangent chord and lilting,

patchworked songwriting pick up speed into quirky, rhythmic

energy, into an electronically charged, almost apocalyptic

peak with the devastating, Enoenhanced 'Out Of The Blue'.

The album's final section knits together songs in Italian

and Spanish with loose, multicoloured arrangements of free

jazz vibraphone, minimalist synth, distant trumpet, and

all around a spaciousness that recalls, if anything, bands

of the Brazilian Tropicalia movement, whose psychedelic

bossa nova whimsy masked deeper metaphysical concerns and

a wry, committed criticism of the status quo.

But at every signpost, there's a derailment or a surprise:

with Wyatt, consistent as his vocal presence remains, the

unexpected is, you feel, central to every song'Just As You

Are', at first listen a soft love song, taps into the compromises,

co-dependency and insecurity present in every relationship.

The loping, lush 'Beautiful War', turns around and strangles

you when the subject matter comes clear: its airiness is

the methodical efficiency of a bomber destroying an anonymous

settlement far below, safe in his cloudless sky. The stately,

waltz-like 'Cancon de Julieta' fragments into the call-and-answer

swoops of Chucho Merchan's bass violin and a weird noise

undertow that befits its setting of Garcia Lorca's words.

Wyatts previous album, 2003's Cuckooland, navigated

a similar journey between familiar and alien; internal and

political-like Comicopera, songs gently whisked you

from wry ontological questioning to cinematic evocations

of 'Old Europe', from drifting, legato laments to jazzy

scuttle. Comicopera is wider in frame, somehow; delirious

with ideas, but with a settled assuredness of vision. How

did it all come together? Did the structure come before

or after the songs?

"It came out of the process. Things separate into chunks

of preoccupation. I'm sort of floating about all the time,

and it's quite disparate and quite chaotic. And then when

I've got an hour and a half's worth I gather it together,

then I sort it out in terms of what state of mind I was

in when I wrote this song or that song, or nicked somebody

else's song, or stopped singing altogether and let someone

else play their instrument. Because I get bored, you know,

of my voice sometimes. Anyway, then you sort it all out,

and in this case it fell into three sort of categories,

really.

"I'm on an animal level, using instinct most of the

time, which is what I like most. But let's sort it out,

help the listener here a bit. Cut it up a bit. This is one

train of thought, that's another. It turned out it took

three trains of thought".

It's a weird listen. You start off feeling quite safe

but then as it goes on it starts to become a much darker

record. It's quite disorientating.

"It's just that, having got past 60, I've done all

the business of trying to tailor things to what people can

digest. You get quite selfish at this age. You just think,

'I've got one last go, possibly, so I'm just going to throw

it out the way it happens'.

"What I do remember is that youth always anticipates

death as quite a dramatic, black and white thing. They romanticise

it, and simplify it and cut it down. But it's a weirder

and stranger journey. You start off, and you know roughly

what's going on. Even if it's strange for you it's marked

out. You become a teenager and think, 'OK, there's sex'.

Then you get a job, and you think, that's adulthood and

you've got there, to a sort of plateau. But then

you could have another 20, 30, 40, 50 years of 'what then

?' Then you're in danger and in the wilderness, much more

than teenagers ever understand about wilderness - they fantasise

about 'weird', but they have no idea what weird really is.

Weird is really fucking weird.

"When you're 50, life is just as unknown to you and

unliveable, difficult and strange, as it is for a 12 year

old. But then, I say all that stuff which sounds really

pretentious, but all I've tried to do is make a really nice

record. I've tried to string nice notes together. And if

somebody's got any patience they will hear them. I don't

put the beats in to help, I just say 'Look, the notes are

there, believe me. Trust me, I've got a beard. How can you

not trust me?'"

I don't know if I trust beards...

"No, well, I would never play a record with a person

with a beard on the front, other than myself. This is why

Alfie never, ever does album covers with me on the front,

because it would put everybody right off."

Ever since I first heard it, I've found your music very

comforting, even when it sounds unsure or sad or critical.

But with this new album I feel more than ever this sense

of you looking at the awfulness of things.

"If it's a bit distressing where I go, hang on in there

because it's quite friendly in the end. I've just tried

not to avoid the nastiness, but say that although the nastiness

is unbelievable, it's not unbearable. That's what I hope.

I would hope that in the end it would be some kind of comfort

because god, there's just so much pain. But you've got to

dig a bit deeper, not to come on all serious, but just to

provide any comfort at all. Beyond the immediate comforts

of orgasm and getting pissed and loud music and stuff. Life

lasts longer than all those three events, which are crucial,

but there's got to be a deep fun going on as well that survives

all the tragedy."

In some ways I'm looking forward to getting older, getting

past a lot of that stuff.

"I'll tell you, it's a lot to look forward to. It's

really nice. It's kind of like climbing up the slippery

bits out of an ocean and getting up to dry bits, and looking

down into the valley you just crawled from of teeming activity

and agony and sleepless nights and all the awful, well,

wonderful things. Both. It's really nice. You think, wow,

I've been allowed to live long enough to have a look at

what's been going on in my lifetime. It's a great privilege."

I didn't mean to bring up the comfort thing so soon in the

interview. It felt a little creepy somehow;

a little too familial. But what the hell: many of my generation

are at odds with the idea of family, at odds with the media

and government's current idealised view of love and domestic

life, but also unsure about the countercultural values our

own parents might or might not have tried to live up to,

all at sea as to how and when and where we'll find our real

homes and real connections. It is easier to look for the

idea of 'family', of closeness, outside our own, and some

of us find it in music, of course.

If we feel rootless, songs like Robert Wyatts (all at once

steadfast and sharp, yet fragile and ambiguous) give us

some tentative roots. While I am sure he'd laugh, embarrassed,

at such a notion, there are people my age to whom his tremulous,

conversational croon has an oddly mentor-like quality, a

cipher for their own feelings about vulnerability, independence,

where to put themselves in this world.

But let's not get too sentimental here.

This is music we're talking about, and much of the reassuring

quality of Wyatts music derives, paradoxically, from his

removal of himself from the songwriting process and his

ability to set the listener afloat in sound. Even when his

lyrics are heavy on the polemic, there's something sonically

selfless about the way he approaches the idea of

the song, which often emerges from shifting sands of resolved

and unresolved melody as if you've unearthed it yourself.

And this fluidity, this oceanic quality that's reflected

in the timbres he works with, reassures by its assurance

that some things are bigger than you and all you can do

is cast yourself adrift in them.

DOTS AND LOOPS

Really, there's only one thing I came here to ask, and that's

how Robert Wyatt makes such music.

So I do. And he scoots around the room, energised, demonstrating,

sounding out notes on piano, trumpet and voice. "It's

very, very simple how I work. I've got a room here; four

walls like anybody else's and a door going through to where

I make tea. Facing me is a CD player and a cassette recorder.

On the left of the mixer is an eight-track recording machine.

Right in front of me I can look out onto the car park and

watch people driving into town and people driving out. On

my right, I've got a baby grand piano. On the right of that

there's a disused fireplace, and then I'll take you back

to where we started; about a thousand vinyl LPs and some

photos of my wife, including one of her smacking her previous

husband in the face, just as a kind of warning to me. Look

at that! That's actually from a film, two stills. Tha'ts

Alfie when she was a little girl. And that's her now.

"This is where I work I just had to cut music down

to very simple things. There are beats in my stuff, it's

just that they're buried. There's a grid, in other words.

I'm very old-fashioned. I want a beat and a tune. There

are two kinds of music really, there's music to dance to

and music to sing. You can have singing music, which has

no beat. You can have dance music which has no tune. The

intriguing exercise which I've embarked on for the last

50 years is to try and combine the two. I think, if I've

made mistakes, I've erred on the side of tune, and let the

beat be buried a bit; like the skeleton of a fish. It's

there, but it doesn't look like a great bony animal.

"Then I work out the piano. About there I can

hit it with my voice" He strikes a key. "Now,

20 years ago I could get up to there, but I can't anymore,

so I have to do all that stuff on something else; trumpet,

or something like that. So, that's notes. Then, I've got

this metronome, which is fantastic;

it's Victorian, I think. Now then, that metronome is

a wonderful thing. It doesn't even rock steady, and there's

a track on the new album where this is the only rhythm section,

the one about 'Hattie in the at tic' [AWOL]. That's all

I used. That's the drumkit.

So, I've got a beat, and the notes, and the trumpet, and

then I've got heaps and heaps of bits of paper with words

on... and I just try and stick them all together, my dear;

that's all I do."

Do you do it every day?

"I play trumpet every day."

Do you write words every day?

"There I hit the buffers, because words and music don't

always fit. The bit where you think about words is a whole

different bit of your brain. It's that lovely transition

zone between words and music that's got some sort of biological

roots in humans. I don't know enough about human biology

to know what the link is".

Is it about finding a balance between what you want to

say and the musical words that will say it?

"Well, I actually think that way round, and I write

more than I sing, because mostly what I write, I write.

That's the form it takes. With music, I don't start with

words; I start with noise, with sound. If it turns into

words then I've struck lucky. You can't force it, though.

"I only make one LP about every five years because

of that. It's not that I only have that many ideas. You've

got to be so lucky. It's like panning for gold: every day

you stick your thing in the water and drag up a bit of mud

and leaf through it. Occasionally you pick something out

and you think, 'Oh, that's really nice. There's a bit of

mineral

there'. You put it in your bag to take home, and music's

like that. Fishing about among all the notes and occasionally

one will turn into a word or a phrase, and then you'll take

it home.

"Singing and talking aren't the same thing. They absolutely

are not. I remember a dreadful moment at a friend's house

about five years ago. A bloke pulled out his guitar and

Alfie rushed into the kitchen saying, 'Oh no, he's going

to sing a song, it's going to kill the conversation dead!

We're going to have to sit and listen to him now.'

He started singing some ballad and you could see everyone's

metabolism slowing down. It's an awfully cruel thing to

say, but people when they're singing gentle ballads think

they're being gentle, but they're being quite interventionist,

actually."

They're forcing you to enter their world.

"It's that kind of ersatz church mode. I much prefer

making records to live gigs now, for that reason, because

I don't want anyone to listen to me when they don't have

to, or don't want to."

So you don't like the idea of reverence...

"I think it's appalling."

Do you still improvise with people?

"Yeah, I do a lot. In fact, even on my records I do.

Most people start with the notes, and the beats, and fix

which ones are going to work and expand on it. I tend to

work backwards in a way. My brain is sort of a cross between

Oxford Circus and a Cecil Taylor concert. Then I just keep

cutting stuff out until I'm left with a followable thread

- reduce it right down to a few words or a few notes. To

me, songwriting is incidental to making music. What I'm

trying to do is make records and I want them to be

complete meals; vitamins, proteins, trace elements, the

lot. "But I always work backwards from chaos into order.

That's really the only thing I do that's totally not jazz

and it's totally... well, I haven't learnt that from anybody.

That's just the way I work."

It's probably an accumulation of all the music you've

listened to.

"Yes, there's just an overwhelming amount of stuff

that you can't deny or chuck in the bin, and it's irreconcilable

so you just have to let it ferment in your brain, and then

your brain will inevitably because you're only one little

pathetic person - will reduce it down to the things that

work for you and keep pushing everything else away and you're

left with the utter simplicity of a Buddy Holly song - or

you're left back with actually being a kind of folk musician

representing an unknown tribe, of which there may be no

other members! Just your own little one-person tribe."

You know, you've probably summed up there one of the

best reasons I can think of to make music.

SIGNIFICANT OTHERS

The most obvious, and pleasurable, evidence of Wyatt's eschewal

of singer-songwriter egotism is the long-standing relationship

he has with collaborating musicians - from rock notables

like Paul Weller and Brian Eno, to jazz musicians such as

trombonist Annie Whitehead, vocalist Karen Mantler, percussionist

Orphy Robinson and loads more. It's not unusual that an

admired musician should be able to cherry-pick others to

work with them, but Wyatt's collaborative recordings stand

out through giving the impression, always, of real musical

dialogues, necessary and organic. Comicopera marshals

a large cast that feels particularly able to draw Wyatt's

compositions in odd, exuberant and atmospheric directions.

"I've given up working with people I don't like,"

he says. "I used to, because I thought they were really

brilliant or clever, but I can't be bothered with that anymore.

Because in the end, musically it's better - people open

out. There's this illusion that confrontation brings out

stuff that's exciting, like on Big Brother-no it doesn't.

It's sort of all right, but you get further and deeper with

empathy."

When Wyatt asked singer Seaming To, who provides the soprano

vocal on Comicopera's 'Stay Tuned', to add clarinet, "She

said, 'I haven't played the clarinet for a while', and I

said, 'Look, it's not fucking Mozart, it's just a few notes'.

I thought she did lovely on it. I know I could look through

the Musicians' Union phonebook and get brilliant clarinetists,

but I wanted someone I could connect with as a human being."

I get the impression you're open to people having their

own take on your songs.

" Absolutely. I don't tell them what to play. The buck

stops with me when I'm editing. They know that. So it's

not in that sense a free-for-all. I will take responsibility

for the end result, which is arrogant but also I don't want

them to get the blame for the wrong notes. It's got to stop

somewhere, because when you listen to a record it's partly

for sound, but also for company. You want some kind of coherent

sense of another person in the room when you play a record.

So for better or for worse when you put on one of my records

you're getting me. I get all the help I can to make it sound

good."

Do you feel like you learn a lot

from your collaborators?

"I couldn't do without them. I left school at 16 and

I can't really read music. I rely on people like [saxophonist]

Gilad Atzom and [bassist] Yaron Stavi and Annie Whitehead,

who are fantastically well-schooled musicians, to hear what

I'm doing and make coherent sense of it. I'm not really

an individualist."

Wyatt's most significant collaborator, though, must be his

wife, Alfie. As well as writing a great many of the lyrics

to his songs, her paintings and collages have been the visual

representation of Wyatt's music over the past few decades,

and are almost inseparable from its sound.

Like Wyatt's songs, her designs are deceptively simple,

their bright colours and irregular shapes belying a complex

fluidity. What I regret most about this day spent with both

of them is that I didn't record the conversation Alfie and

I had on our drive back, an exchange about writing, feminism,

war and families - and probably most of all, how lyrics

and music work together. I remember it, though. It was great.

Do you tell her what you want her to do with the artwork?

"I wouldn't say a word. I let her get on with it. She

knows what the songs are about because she wrote half of

them. I know from doing stuff myself I don't need someone

looking over my shoulder. I can get there myself, otherwise

it's not a journey. I don't always know what's going in

Alfie's head."

Do you ever disagree?

"I never disagree with Alfie."

Some of Benge's most moving lyrics on Comicopera

are those of 'Out Of The Blue', which was provoked by the

Israeli bombing of Lebanon last year. Focusing in on the

domestic, it tries to express the sheer sudden horror of

a house - a simple, safe place - destroyed by an anonymous

enemy. Wyatt's turning to other languages for the remainder

of the album after this is no coincidence.

"It's after the line, 'You have planted everlasting

hatred in my heart'. It follows a woman whose house

has been bombed to bits by some clever dick in an aeroplane

- 'You've come to my door but you've blown it apart, so

you might as well come in through the roof or the ceiling.

You've fucked up my house - fuck you. There's nothing I

can do, I haven't got a bombing aeroplane myself.' What

do you do? What Palestinian women do is they do encourage

their sons to and fight back, but of course that leads to

more tragedy. But at the same time you can't just wipe people

out by bombing them.

"Alfie was reflecting on the cycle of violence, where

you may not intrinsically feel violent, but if great violence

is done to you then one of the responses is to be violent

back, and it's the point at which all these philosophies

about trying to be nice just collapse in the face of that

excessive rape of a soul. And I'm just not clever enough

to know what to do next, so I just sang in foreign languages

and did a bit of free jazz..."

|

Did you feel like there was nothing you could say?

"I just felt completely ill-equipped to come up with

an appropriate response. So then I do what artists do, which

is drift off into some kind of fairyland. The whole last

section of the record is about trying on different alien

guises: foreign language or a revolutionary rhetoric or

a bit of free jazz, Orphy Robinson on vibes going bonkers,

or surrealist dream-world stuff. I just turn back to my

original craft, which is to try and make a nice sequence

of notes that don't ignore reality. It sounds so pathetic.

I'm not a wise old man. I can think, I can think, I can

think, and then I just get stuck.

"I can't compete intellectually in words with where

I've got to musically. I do feel like I've got much further...

when I try and catch up with words it's sort of a bit clumsy...

He picks up a weathered-looking brass instrument.

"Annie Whitehead, who plays trombone on the record,

on the fourth track of the album ['AWOL] she plays this.

Alfie got it in a car boot sale. It's got the wrong mouthpiece

on it. It's called a baritone horn. I tried to play it,

but I can't fix the notes! The reason I mention that is

because I said to Annie, 'I'm having trouble with Concert

B - how do you hit that?' And she said, 'Robert, there's

no short cut." Annie's been practising hours a day

for 40 years, and she was politely telling me there were

some things you just can't get to straight away. "

He laughs. There's no short cut to a low Concert B."

FREE WILL AND TESTAMENT

Do people still ask you a lot about your politics?

"It still comes up a lot. The moment I joined the Communist

Party I knew it was something I'd have to deal with for

the rest of my life and it would be a real obstacle for

some people, a point of interest for others or a point of

contempt for others."

How do you feel about it now?

"I'm always nervous about sounding like Cliff Richard

talking about his Christianity, but it's just that I personally

have found a way of understanding the world that makes sense

to me and I get more sheer intelligence - applicable ways

of looking at the world -than I do from Marxists than I

do from religion as the world is commonly used. I do see

the power shifts and politics in the world in terms of military

and economic power. Not in terms of an answer, but just

an understanding of the process as we're living through

it. That's all I'd say about it."

Would you say all your music is political?

"I would go further than that. I would say I'm more

consistently a political animal than I am a musical one.

In other words, who I am and the privileges I have come

from political reality. And the fact that I've chosen to

be a musician out of the various occupations I could do

is sort of secondary, actually, to me. I love music. But

I did anyway, long before I was a musician. As a teenager,

music saved my life. But as a teenager I thought I'd be

a painter.

" Thank god for rock music for one thing: that it went

back to basics. Rock music is about a return to folk music.

You don't have to know anything. You just have to get an

instrument in your hand that plays a note, and sing, and

anyone can do it.

"I started out from there. I was really grateful, because

in the Fifties when I was listening to jazz or Stravinsky

or something, it didn't occur to me that I'd ever be able

to play it. There's no short cut to that stuff. But with

rock'n'roll there is a short cut - you just sort

of... do it. So that's what I latched onto. First of all,

it wasn't very philosophical, it was more like, how do you

get to dances, and one way was being the drummer. So that

sort of thing - very simple."

Is it still very simple?

"It has to be. Any information I get, I try to take

it all on, but in terms of processing it, I have to reduce

everything back to all those teenage things - is there a

beat somewhere, is there a tune somewhere? That sort of

thing."

He pauses.

"Are you hungry? You must be hungry."

|