| |

|

|

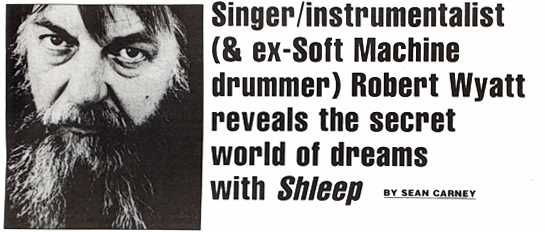

Singer/instrumentalist (& ex-Soft Machine drummer) Robert Wyatt reveals the secretworld of dreams with Shleep - USR U.S. Rocker Magazine - Number 6 - June'98 Singer/instrumentalist (& ex-Soft Machine drummer) Robert Wyatt reveals the secretworld of dreams with Shleep - USR U.S. Rocker Magazine - Number 6 - June'98

Robert Wyatt? Who the hell is Robert Wyatt!? Well, unless you buy a lot of out-of-print vinyl, you might not have heard of the man before. But now with a new record, Shleep, available domestically from Thirsty Ear and a reissue of his entire back catalog planned for summer release, it's time to catch up.

Robert Wyatt was a founding member of the '60s art rock band Soft Machine from Canterbury UK. Although Soft Machine debuted in the middle of the decade-long British rock explosion, the band was quite different from its contemporaries. First off, Soft Machine - in its classic configuration - had no guitarist. Instead, the musical focus was on the hyperactive interplay between Hugh Hopper's fuzz bass, Mike Ratledge's even fuzzier organ, and the drumming and singing of Robert Wyatt. The band careened recklessly from cabaret-sounding jazz to completely frazzed-out rock, bypassing the flaky psychedelic

idiosyncratic approach and took Soft Machine along on the Experience's first U.S. tour in 1968.

Wyatt's percussion style was unusual in its fluidity and ratty energy - a mid-point between Keith Moon's manic approach and the precision, "pro" sound of Bill Bruford. Even more remarkable than his drumming was Wyatt's unbroken, high-pitched voice that sounded more like it belonged to a teenage boy than a man. His phrasing on the first three Soft Machine albums is amazing. He breaks the words at unusual points and often indulges in "wordless vocal guitar solos," scatting along in an eerie register, tripping and trilling along with the melody. His words were exceptional, too, and had nothing in common with the insipid "let's boogie" come-ons of other English bands of the time. He employed whimsical surrealist imagery that was also wise and subtly political. "Virgins are boring," Wyatt sang on "Pig" (from Soft Machine II). "They should be grateful for the things they're ignoring."

Wyatt left Soft Machine after three albums to form Matching Mole, an even more spontaneous and jazzy ensemble. Then, in 1973, Wyatt fell from a window at a party and was paralyzed from the waist down. Although this ended his career as a kit drummer, Wyatt was soon back at work, singing, arranging and playing a variety of instruments on classic albums by luminaries like Brian Eno (Wyatt contributed to Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy and Music for Airports — some pretty cool credentials). Wyatt also began what is now a twenty-five year long solo career that de-emphasized rhythm for vocal and harmonic exploration. On albums such as 1974's Rock Bottom and 1975's Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard, Wyatt plumbed his emotional depths, extracting some of the most heart-rending personal music of all time. His newest record, Shleep, is a bit more light-hearted than his '80s work (which saw him delve into Marxist politics) and features guest musicians like Eno, Phil Manzanera (from Roxy Music), Paul Weller (from the Jam), and avant garde saxophonist Evan Parker.

USR was lucky enough to have the opportunity to spend some time chatting with Robert Wyatt on the phone early in May. He doesn't do many interviews, but he spoke candidly with us about what it means to live as an artist in the late 20th century, and his joyful lust to create infected us all month long.

It's been a few years since you've released any material. How did you decide it was time for a new record?

Well, I spend months on end working on piano ideas and cymbal ideas and trumpet ideas at my home, I'm always writing bits and pieces of songs but only at certain times do they come together into a coherent piece. I can't force it - I can't turn the tap on and POOF! a song comes out. Things have to come together naturally, organically. And when they do, I get into the studio as quick as I can.

Do you have other collaborators in mind when you're crafting the song ideas?

Ever since the early '70s, I've found that the safest way to record is to take responsibility for everything. It's as if you were the captain of a ship: it's a good idea to be able to do everything you're gonna ask everyone else to do in case they get washed overboard. I really try to be prepared to play every instrument myself and only when I need another voice do I invite someone who I think is appropriate to join me. That way, I'm not dependent on them but they can enhance what I do - sometimes beyond recognition. When I'm mixing, I take that into account and change what I already planned.

So the contributions sometimes surprise you?

Yes, though over the years I've learned a bit better who is most happy in each particular context. I don't always get it right but I really try. I attempt to take into account each musician's harmonic palette and the pace they like to work at beforehand so I don't throw them into an uncomfortable situation. If I'm working on something that is rhythmically or harmonically obscure, there are certain jazz musicians that would be more comfortable with that than rock musicians. Rock musicians possess other important qualities, having mostly to do with dynamics. They can really bear down on a tune if they're harmonically comfortable.

I was very lucky this time because there was a such a helpful and friendly bunch of people that came by the studio. I got more and more happy because I realized I wasn't going to have to rely on myself for everything.

Do you think that's a strength of jazz and rock music - the collaborative spirit?

Yes, that's an advantage those musics have. When I was young, my initial tendencies were towards "purist" artforms like painting and poetry because a person does it entirely themselves, straight from their imagination onto the paper. The trouble is "pure forms" don't reflect what real life is: a constant process of interaction and adjustment to the things going on around you. And I've really understood that listening to jazz. I'm so grateful to jazz because it established the idea of an inter-relationship between the composers and the performers, constantly flowing, constantly shifting. Despite the fact that we're not playing what anyone would think of as jazz, those of us working in the more improvised and extended areas of rock should be thankful for everyone from Louis Amstrong to John Coltrane for having opened up the whole range of collaborative creativity.

Miles Davis used to arrange music simply by choosing the players and then letting their personalities shape the sound.

That's right, yeah. I was just listening to Miles Ahead and on one track Miles Davis makes a humorous reference to "When the Saints Go Marching In." To do that, Miles is depending on the other musicians to know what reference he's making - they don't automatically lock into "When the Saints," but they accommodate him for a few bars. They all faintly echo the '20s record he's referring to and then they zip back into the '50s, which was when Miles Ahead was recorded. To accomplish that depends entirely on knowing who you're with and that you can trust them.

I suppose it's like what some socialite might say about how you invite people for a party: a good party depends on who you've got sitting next to whom. But it doesn't mean you can control what they say! If you've chosen well you can't go wrong, however.

It's been suggested that the ultimate anarchist art grouping is a party.

Oh, that's a very good idea! Of course, there's always someone who throws the party and there's always someone who has to say "Fuck off, I want to go to bed!"

And someone who has to do the dishes the next day...

That's absolutely right. As Noam Chomsky said, "Anarchy is not a state that can be achieved but it's a useful tendency that should be applied at all times."

As far as the lyrical imagery of Shleep is concerned were you going for an overall concept or unity?

My initial collaboration for the record was with Alfie, to whom I'm married. I turned to her words, the notes she made, and her poems because, although I had a lot of musical ideas, I had very few lyrics in mind. Her words seemed to be based around the imagery of birds: birds in flight and birds not able to fly, etc. This coincided very well with the almost permanent dream state I've been in the last few years, a narcotic state without narcotics - which is an ideal slate to be in if you can manage it! Hahaha! It's what you'd call state of grace or luck. Real life doesn't let you live that way too often, but I aim for it and Alfie's lyrics aim for that as well.

I also think that as you get older and heavier, the lightness of birds becomes more and more romantic. At least it seems romantic lo me — I always eat too much. So I combined Alfie's vicarious bird fantasies with my yearning to recapture the wonderful world of dreams. I know that sounds like a cliche, but I just love dreams. The more I look back on my life I'm just so glad for those dreaming moments. Everything is good about dreams. Even the worst nightmares are great - you wake up thinking. Wow, thank God that wasn't true! But if it's a good dream then all the better, and that's the theme of the album.

Do you have waking dreams?

Yes, crepuscular dreams - dawn/dusk dreams. They're dreams that emerge right as you wake up and creep in on you as you start to go to sleep. There are other dreams that happen while you're fully asleep, but they're hard to recall and pin down. Crepuscular dreams - those moments between being asleep and being awake - are the maddest. The closest parallel we all know, even if we can't remember our dreams, is when we get drunk or stoned. And maybe that's why we get drunk and stoned -to recapture that magical half-world. It can be a nightmare or it can be magical. And there's no one, even people who are really boring and dull, who doesn't have those moments where the most amazing, fantastical thoughts go through their head. We all have them - it's just a question of harnessing them, which is one of the jobs an artist takes on.

Have you always dreamt so vividly or have you used special techniques to enhance the experience ?

I absolutely have. I've always been involved in listening to music and looking at paintings and I realized fairly early on that what made art so extraordinary was that it took me back into the world of dreams. That's what I liked about art long before I ever made my own.

What kind of paintings do you like to look at?

Well, basically those from the first hall of the 20th century in Europe when people got together around Paris. Not necessarily just French painters - although I love Matisse and Bonnard. But also the ones who arrived in France, like Chagall from Russia or Picasso from Spain. That whole period is superb, right up to the American abstract expressionists in the middle of the century like Jackson Pollock. Those paintings are still my reference points, even more than anything that has happened since in any other artform.

In the '80s, you became deeply involved with the communist cause and your art took on a more political slant. How did that happen?

When things are on my mind, that's what comes out. In the '80s, for example, I was deeply troubled by the nasty end of the cold war. It wasn't that I was trying to be political or that I lived in fear of atomic bombs, it's just that the times were so disturbing they got deep inside. It was an intellectual horror at the banalization of ideas by our Prime Minister at the time, with her moronic cliches and the fact that she was going down so well in the world. It seemed nightmarish to me. I have some pride in English people and I was happier when we were represented in the world's eye by John Lennon, quite frankly!

Have you left that state now?

No, I would say that state has left me. We now have governments that have mastered the art of not representing anything in particular. It's turned into a kind of ideological soup. They don't say anything that could offend anyone. Intellectually, I still feel a certain distance but how can you fight soup? I mean there's nothing there - it's all too cloudy and nebulous. It's impossible to tell what you're up against. So to that extent, my revulsion seems kind of diffused.

All I can do is stick to what I know is right and defend it at such moments when it's clear to me. And, God help me, keep quiet when I don't know what I'm talking about.

Don't you think that just making art is a political statement?

Don't you think that now more than ever, people are looking for things that are imaginative?

Ugh, I have no idea what people are looking for. I'm certainly looking for the imaginative but I'm not sure what use it is. There's a danger in thinking that great works of art and imagination can really profoundly alter anything for the better. For example, my father was a very idealistic man, a Christian socialist of a very English type. He believed what he was fighting for - he was a soldier in WWII - and he really loved classical music. But the people who had created the most majestic classical music in the world at that time were from Germany and Austria and were themselves the seedbed of the most cruel and heartless phenomenon the world has ever known: Nazism and Fascism. It left my father totally confused... and me, too.

I don't know what people want or what they're gonna do with it, and that's the truth. All I know is that an artist should always try to be authentic and be true to himself and hope that that's good enough. If that doesn't work, then there are forces at work too powerful for anyone - let alone me - to know what to do about. It's not a soundbite, I'm sorry. After years of thinking about it, it's gotten harder and harder to work those things out.

One of the things that makes Shleep sound so unusual is the way you extend the melody lines over many bars of the music. Do you sing along with the riffs as you're creating them?

Yeah. I was talking about my dad - he was a big influence on me in terms of music. He got me interested in classical music. I remember when he played me my first LP, a piece called "Antarctica" by an English composer named Vaughn Williams. It went on and on - I had never heard anything quite like it. I was very impressed because up until then I had only heard 78s and just the very existence of LPs meant that ideas could flow like oceans, not just go round and round and disappear down the plug-hole like water in a sink.

As much as I love pop music, which I absolutely do, it seems to me that the length of the early 78s still govern pop. Everything is forced into a two or three minute soundbite song, and I've always felt constricted by those restraints. I love pop, and God bless the people who do it well, but it gives me claustrophobia. I like the idea of things flowing and twisting and turning and going where they will.

It's funny how mechanical considerations have often determined artistic standards in music.

That's right - the three minute single is a result of technical considerations. It's very useful in a way. On those old jazz records they kept those solos short and sweet and didn't ramble on too much. It was a good discipline. But in the end, there's just so much more to be done than that.

Sure - those same players were really cutting it up live.

That's why it's so wonderful to hear live concerts by people like Charlie Parker, extending chorus alter chorus, unravelling the whole song. And we would never have known this if we'd only heard 78s.

Yep, live is where it's at. What about you, do you still perform out?

No, I figured if Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly can get away with not doing any live gigs, so can I.

That's not the same thing at all, Robert!

I suppose it's not. Playing live is difficult because of the way I make my records. I put all the layers on myself in the studio. It would be hard to re-create that live. Also, I've found that I've got stage fright. I've lost my nerve. Being in a wheelchair has sort of removed me from access to the world of getting on and off airplanes and cars and buses. The everyday world of the touring musician seemed to recede into the distance after a year or two of being in a wheelchair. I get invited to do gigs, but if I said yes to one, they'd be offended if I turned down other ones. Plus, when I'm singing a song my technique is very often shit and it takes me four goes to get it in tune whereas live, the first go is all you get. I'm not Aretha Franklin, I can't hit it on the note every time! I'm much more competent as a drummer than I am as a singer.

But you used to sing and play drums at the same time...

Yeah, but the fewer takes anybody has of that period, the better, as far as I'm concerned.

Would you ever have imagined as a child creating music as you are creating now?

No, I assumed that music was completely outside my reach. I was interested in painting and Dadaist art at the time. I had no idea what I was going to do when I got older. I imagined I would be a comic or a comedy writer because I've always enjoyed word games. It would never have never occurred to me that I would be a musician or a singer, it just sort of happened in the '60s. I was crap at school and I couldn't handle any of the careers I was being trained for. So, like a lot of people of my generation, I went into something where you need no qualifications whatsoever — rock music.

It's interesting that you bring up Dada and comedy. My friend Peter has always said that while Dada destroyed modern art, it was a boon for comics.

Absolutely! Comedy is such an underestimated art-form. The ability

to be funny is as great as the ability to play violin. The best comedians are as good as the best artists in any other idiom. Maybe it's because of my early introduction to Dada that I feel so confident in saying that.

A lot of your lyrics -and even your melodic ideas - tend to be whimsical and comedic. But I'm impressed by the deeper sense of feeling that's also there. And I think that's what was so great about the Dadaists, too. A lot of people who came along after them in the artworld missed the humanity of it.

Well, I usually have to have two reasons for doing

something. I do things that are amusing to me because I try to avoid boring myself.

That's number one. But secondly, "interesting to me" isn't enough because I know from having a record collection that albums that are just novel or interesting only get played while they're new and then, after I get used to them, I don't want to play them anymore because I've gotten the point. I've found what I really like about the music and art that I love the most is that even when I know it by heart, I still want to hear it again. And that seems to me to be a whole other level beyond being surprising or witty. So I try to think about records I like and what keeps me going back to them twenty or thirty years later. It's very hard to me to say what that is, it's beyond words really. When I really think about things like that, I'm in the land of music.

Ah, but that's the great thing about music, which is a totally abstract artform. Like with classical music, the person off the street can appreciate it for the pretty melodies but there are far deeper complexities to ponder, too.

Absolutely right. Words fail me when I try to describe how important music is to me. I have fanciful ideas about that. Perhaps because our animal ancestors were originally underseas animals, we need the viscous connection that music provides - we want to re-create a swimming environment now that we're on dry land. Music connects us ear to mouth, mouth to ear in an invisible physical link through the air. We all know about that. When a baby is born the first thing it does is cry to its mother. Only when it gets a tit in its mouth does it shut up. The noise is for a reason. There's something pretty serious going on the whole business of making a noise at all. Our lives have depended on it since the moment we were born.

Sean Carney

Robert Watt's new album, Shleep, is available from Thirsty Ear (274 Madison Ave. #804, NYC 10016).

|