| |

|

|

Who

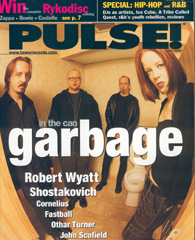

is ROBERT and WYATT matters - Pulse! N° 170 - May 1998 Who

is ROBERT and WYATT matters - Pulse! N° 170 - May 1998

WHO IS ROBERT AND WYATT MATTERS

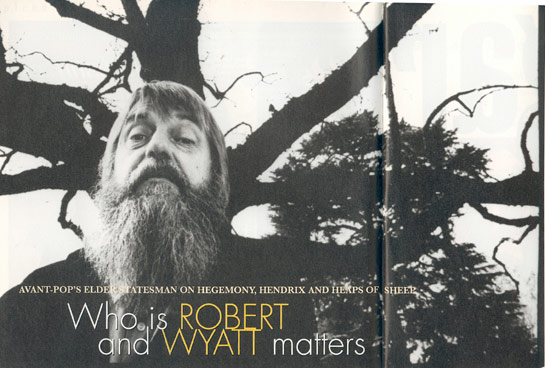

AVANT-POP'S

ELDER STATESMAN ON HEGEMONY, HENDRIX AND HEAPS OF SHEEP

BY BILL FORMAN

PHOTOGRAPH BY GUIDO HARARI

Given free will, Robert

Wyatt would prefer to live his life as part of a dance

rather than as if there were some great weight on his

shoulders. "Most people think they ought to stop

being trivial and get serious, but I'm trying to get light

from heavy," says Wyatt in the wake of Shleep

(Thirsty Bar), the Soft Machine founder's most congenial

and collaborative album in many years, featuring contributions

from Brian Eno, Paul Weller and other friends, old and

new. "When you let it, life can be so heavy, gravity

becomes too great, and you can hardly function. And I

think the thing is to somehow become some kind of gas

and float above it."

Wyatt has surely had his run-ins with gravity: Both his

touring and drumming career came to an abrupt end in 1973,

when a fall from a third-story window left Wyatt paralyzed

from the waist down. By that point, he had already quit

his band Soft Machine and started another called Matching

Mole (pidgin French for Soft Machine). Forced to abandon

the custom Maplewood kit that Jimi Hendrix Experience

drummer Mitch Mitchell had given him after Hendrix and

the Softs toured America together, Wyatt switched to keyboards

and set about reconstructing himself as a solo artist.

Wyatt's voice, a plaintive countertenor he once likened

to "Jimmy Sommerville on valium," has always

been unconventional yet oddly accessible. His sad choirboy

vocals float serenely through an ambient soundscape of

understated keyboard and percussion, colored by the subdued

improvisations of his avant-jazz friends. If the most

blatant jazz-rock fusion acts combined an excess of technique

with a paucity of ideas, Wyatt's approach was more fission,

a contemplative yet compelling mix of free jazz, naive

pop and English eccentricity.

A year after the accident, Wyatt recorded an altogether

unlikely cover of the Neil Diamond-penned Monkees single

"I'm a Believer," which became a hit and landed

him on the BBC's Top of the Pops. Accompanied that

evening by Pink Floyd's Nick Mason, Henry Cow's Fred Frith

and future Police-man Andy Summers, Wyatt lipsynched his

way through clenched teeth after a BBC producer insisted

that his wheelchair was unsuitable for prime-time televiewing.

Meanwhile, back in the real world, Wyatt's music grew

simpler, more direct, and-with the 1975 death of his friend

Mongezi Feza - intensely political. "When Mongezi

died, I suddenly realized that apartheid was killing my

closest friends, and that's when politics right across

the world becomes just as personal as anything can be,"

says Wyatt of the exiled South African trumpeter featured

on Wyatt's Rock Bottom and Ruth Is Stranger

Than Richard (two of the six Wyatt albums Thirsty

Ear plans to reissue this year). "You can be theoretically

anti-racist or anti-apartheid and say, "I don't think

people should be allowed to have a kind of internaI slave

population servicing their businesses" - which is

what South Africa was, a kind of internaI colonization

- and you can know that abstractly. But when you actually

have South Africans who come here just so they can play

music together and when, in their early thirties, they

start dying because you find out they've been living on

no food and too much gin from the gin palaces since they

were about 9 years old, and even after coming to England,

they would be so terrified every time they saw a policeman

that they would nearly have a heart attack. Mongezi Feza

died a quite unnecessary death of double pneumonia whilst

he was in a psychiatric hospital, and he was really only

in a psychiatric hospital because he just couldn't handle

whether he was allowed to deal with white people or not.

He was so confused about what the relationship now was.

So then he died. I had actually planned to make a lot

of records with him. I had thought I' d found my ideal

partner."

Wyatt's songwriting reached its political apex with 1985's

Old Rottenhat, a starkly beautiful album whose

musings on the anti-imperialist theories of Noam Chomsky

and the troubles in East Timor earned a mixed critical

response. "WeIl, I'm really glad you heard [the album'

s minimalist aesthetic] as clarity, because some people

heard it as not much going on, which is missing what was

going on, I think," says Wyatt. "I mean, there

are some people who just don't like my politics, and I

understand that, but sometimes they sidestep that by saying

they don't like my style. I don't mind. You can't tell

people what to listen to. You have to be grateful if they

listen to anything you do, really."

It was also during the mid-'80s that Wyatt released a

series of 7-inch cover singles on Rough Trade, including

the Billie Holiday classic "Strange Fruit,"

an anthemic remake of Chic' s " At Last I Am Free,"

and the anti-war ballad "Shipbuilding," which

Elvis Costello wrote for Wyatt so that he could hear it

sung by the saddest voice in the world. "I think

part of the job of a-can I use the word artist? - is not

just to make objects, but to find the beauty in objects

that already exist and to represent it. It's not that

something has to be new or indeed perhaps that

anything ever can be new, but somehow you must

make it new. And that's really what I wanted to

do with those songs."

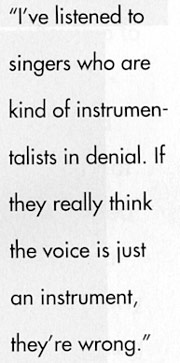

As a vocal interpreter, Wyatt prefers the understated

style of, say, Chet Baker over the melismatic maneuvers

that have become de rigueur for contemporary jazz vocalists.

"I've listened to singers who are kind of instrumentalists

in denial," laughs Wyatt without naming names. "If

they really think the voice is just an instrument, they're

wrong. The fact is if somebody is going 'Oooda-da-deeda-dee-da,'

you know it's a person doing it and there's no

way it's like listening to a trumpet or a saxophone.

We all tend to listen to voices quite differently, which

perhaps goes back to childhood when we listened out for

our mother's voice. So the human voice carries with it

something that no other instrument does, and you just

have to remember that when you're singing."

Wyatt says he someday hopes to record an album's worth

of Gershwin-era covers: "You know, the Nazis' definition

of degenerate music was mournful Jewish tunes sung by

Negroes to sexual rhythms, or something like that. Now

if I were an American, that's something I'd be really

proud of. So I really would like to do some more of those

mournful Jewish melodies. But if I'm getting ideas for

my own tunes, they take precedence. Not because I think

they're more important, but because if I don't do those,

nobody else will."

Which brings us back to the long overdue Shleep,

Wyatt's first full album in seven years. This time out,

politics seems to have taken a backseat to semiotics,

with Wyatt's crafty wordplay evoking the more enigmatic

lyrical terrain of his early work. "I'm not by nature

into either confessional personal songs, particularly,

or polemics in songs, particularly ," says Wyatt.

"Even when I was writing a lot of songs with overt

political references, an awful lot of things I was thinking

about didn't get into the songs. Songs aren't just sentences

set to music. They have to come through [in] that hallucinatory

form. They come from somewhere else.

"Actually, a number of Shleep's songs came

from Wyatt's wife Alfrede Benge, whose poetry he is forever

finding around their old wooden dacha deep in the English

countryside. Thus the title cut, recorded over Alfie's

mild objections, with its image of an insomniac's sheep-counting

gone wrong:

| |

Each sheep,

where it landed

refusing to exit, remained.

(Creating a vast writhing

heap growing fast on the left). |

"I couldn 't waste that,

could I?" laughs Wyatt. "She thought it was

a bit trivial, but it just made me laugh, and it made

Brian Eno laugh, too. So we did it anyway. You know, she

writes these things and then I find them and then that's

what happens. When you're in the same house with somebody,

you can't hide everything."

Wyatt has paid tribute to his wife on past recordings,

most notably on the surreal " Alifib" and poignant

"P.L.A. (Poor Little Alfie)." On Shleep,

that tradition continues with "The Duchess,"

a loopy number in which Wyatt vows:

| |

"My wife

is old and young,

so sweet with her poison

tongue,

on her evenings off she

blackmails toffs, but her

secret's safe with me." |

"We actually wrote 'The Duchess'

together, but I got writing credit because she didn't

want to be associated with such silliness," he says

of his partner, who might have known better after so many

years. "That's right," says Wyatt with a laugh,

"it' s a bit late now, isn 't it?"

|

|

Alfie isn 't the only old friend who

turns up on Shleep. Roxy Music vets Eno and Phil

Manzanera (who lent Wyatt the use of his Gallery Studio)

also help shape the sound, as does jazzman Evan Parker and

trombonist Annie Whitehead. Citing the "courage of

old age," Wyatt even dusted off the trumpet he hasn

't played on record since Soft Machine days. "My excuse

is this," says Wyatt, sounding only slightly apologetic.

"The particular people who make the exact sound I want

to hear on trumpet - Mongezi Feza, Don Cherry, Miles Davis

and Chet Baker - have now all died. I really love the great

jazz trumpet tradition, you know, people like Clark Terry

and Maynard Ferguson and the Marsalis School and now Roy

Hargrove, but I'm not trying to do any of that. I'm just

trying to extend the range of the song when I'm playing."

With one foot in the folksong tradition, Wyatt has always

been more tolerant of simplicity than his jazz friends:

"Given that I'd been brought up on the sort of harmonic

preoccupations of Bartok and Thelonious Monk, how could

I possibly be interested in people who use basic chords

and rhythms? And the point is that there is something else

going on which transcends the obvious analysis of whether

or not this is a complicated or interesting chord. There's

something way beyond that with a good singer, someone like

Bob Dylan, who just has one of those magic voices."

Wyatt, in fact, pays tribute to Sir Bob on the "Subterranean

Homesick Blues" - inspired "Blues in Bob Minor,"

which culminates, by the way, in a caution not to let the

"gringos grind you down." ("So anybody who

says there's no politics on this, just point them to that

last line," Wyatt says with a laugh.) It's also one

of the tracks that features Paul Weller, who was recording

down the hall and volunteered his guitar services, just

as Jimi Hendrix once stopped by a Wyatt session decades

ago and asked if he could try adding a bassline ("You

wouldn 't have to use it," whispered Hendrix) . "Funny

enough, Paul Weller is the first person I've met who had

that same intensity of presence when you're in the room

with him, but is equally gentlemanly and modest about what

he can do. Hendrix was always worried that his singing wasn't

good enough, or his guitar solos were too long or he couldn't

write songs as interesting as Bob Dylan. ln that sense,

he was almost the opposite of most other guitar legends

that l've met, who were very full of themselves indeed.

Hendrix was just a considerate person, really; can you imagine

that in the '60s!?"

Shleep also boasts a kind of reunion with former

Soft Machine mate Hugh Hopper, who provided the melody for

"Was a Friend." "He occasionally writes a

song that's too simple for the jazz treatments he'll use

for his own groups, so he'll send them to me and ask if

I would like to use them," says Wyatt. "But we

haven't actually met for a long time." Still, Wyatt's

lyrics for "Was a Friend" convey a sense of bittersweet

reconciliation, a sentiment that resonates throughout much

of the new album:

| |

"Old wounds

are healing.

Faded scars are painless -

just an itch.

We are forgiven. It's been a

long time." |

"There are some songs that you couldn 't even write

in your twenties, because you don't know that yet, and I

think this is probably one of them," says Wyatt. "That's

one of the advantages of surviving, you get time to find

these things out."

|