| |

|

|

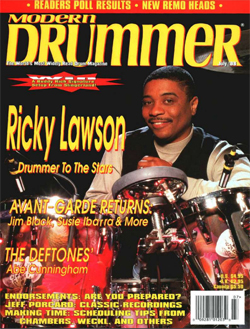

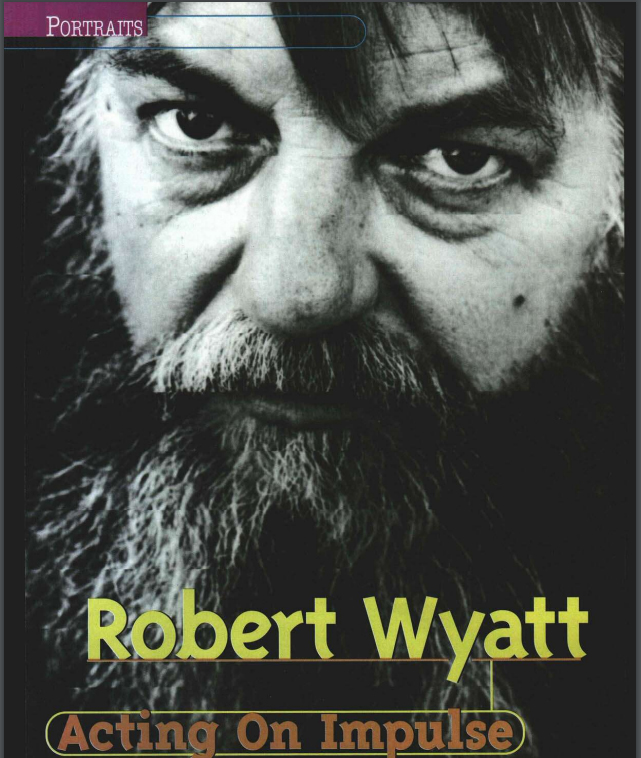

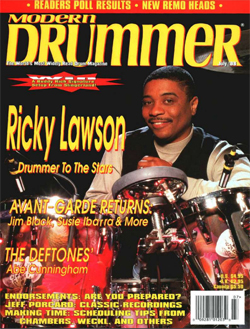

Robert Wyatt - Acting On Impulse - Modern Drummer - July 1998

Robert Wyatt - Acting On Impulse - Modern Drummer - July 1998

|

|

Few musical careers parallel Robert Wyatt's. As the drummer and singer with England's Soft Machine, Wyatt literally

helped birth the genre of jazz-rock in the mid '60s. After

four albums and mounting tensions, Wyatt split, took a

stylistic about-face, and released a handful of amazing—if

esoteric—solo albums. He never looked back at the potentials of stardom, though, and in fact seems to relish the

artistic freedom available outside the mainstream. When

the topic of Sheila E's mass exposure via a 7-UP commercial

is brought up, Robert, tongue firmly in cheek, quickly

responds, "Well, there's been no 7-UP commercials this way—though it has a busy year." |

| |

by Adam Budofsky

|

|

|

child prodigy born to British intellectual

"bohemian" parents, and mostly self-taught on drums, Wyatt's taste for

modern jazz and twentieth-century classical music helped make Soft

Machine one of the most critically

acclaimed bands of the '60s. Along with keyboardist

Mike Ratledge, guitarist Daevid Allen (who left early

on to form the inimitable Gong), and Kevin Ayers (bass,

soon to go solo), the group baffled audiences with their

music, which clearly had more to do with amping-up

Coltrane than weirding-up the Stones.

Despite most people's inability to comprehend the

odd band from Canterbury, Jimi Hendrix invited them

to open up his 1968 American tour, and forward-thinking musicians in attendance began to dig their unique

sound. Of particular note was Wyatt's unbridled kit

work, which was oddly accompanied by his fragile yet

emotive vocals.

Directly after leaving the band, Robert formed the

group Matching Mole, participated in a number of side

projects, and released his first solo album, The End Of

An Ear. A fall from a window in 1973 left him paralyzed

from the waist down, after which his albums took a

fascinating turn. Without the option of heavy kit

excursions, Wyatt's music became rhythmically simpler—but more detailed. The treatment of every element

now took on much greater importance: The subtle

adjustment of a ride pattern signaled a change in

scenery, the turning off of snares beat a new path

through the woods. "Despite all this highfalutin education," he says today, "my songs are very simple. They are nursery rhymes half the time."

Wyatt also collaborated with an astounding diversity

of artists, including jazz pianist Carla Bley, intellectual dance-poppers Scritti Politti, electronic/soundtrack

legend Ryuichi Sakamoto, and Namibian consciousness-raising group the Swapo Singers. This last project

in particular highlights his passion for political

activism, which continues to be a constant source of

inspiration.

Today Robert Wyatt holds demigod status among a

small but fanatic group of followers. Among them is

Elvis Costello, who co-wrote the magnificent surprise

hit "Shipbuilding" specifically for him, as well as

Brian Eno and Paul Weller, both of whom made important contributions to his first long-player in seven

years, Shleep. Modern Drummer caught up with Wyatt

upon the release of the album.

AB: What have you been doing since your last album,

Dondestan?

RW: I've done some singing for other people. A friend of

mine, John Greaves, did a record called Songs, and I sang

three tunes. More recently I sang a bit for Austrian composer Mike Mantler.

AB: You've worked with Mike in the past.

RW: Yeah, I have. One of the most exciting things I've

ever sung against was the rhythm section that he and Carla

Bley provided with Jack DeJohnette on drums on The

Hapless Child.

AB: Your new album seems to be more about collaborations than past records. You recorded at [Roxy Music guitarist]

Phil Manzanera's studio, and you played with Brian Eno again,

and Paul Weller—for the first time?

RW: Yes, although we've been involved in some of the same sort

of political pressure groups, but never as musicians. People have

been telling me that I should really work with some other people

occasionally, [laughs]

AB: You have done your share of collaborations, though.

RW: I have played with a lot of people, but I do like working on

my own. It's a paraplegic thing: We like to do what we can whenever we can, given that in a lot of the world we can't do as much

as other people. So even on this album, I've done as much as I

could myself. I try and be my own sort of mini-group. But I wanted the company. I get lonely out here, [laughs]

AB: Are you way out in the country?

RW: Yeah, I'm in a little country town. But I just thought it

would be nice to see some of those musicians I used to know in

London, and because Phil Manzanera's studio is very near

London, I felt free to ask people on a quite casual basis to come

'round for an afternoon or two.

AB: A couple of people actually got pretty involved.

RW: Paul and Brian—neither of whom charged me anything,

incidentally—actually mixed some of the tracks that they played

on. I thought, well, they've made their contributions, and they

worked very hard. I was really grateful, and I also didn't want to

misuse their contributions. But they both seemed most concerned

with getting my voice right in the mix, which was very kind. And

I have to thank Phil Manzanera for providing an atmosphere

where I felt I could take time on things.

AB: One thing that is consistent throughout your career is a willingness to let the ride cymbal provide almost the entire driving

pulse in a song. From the new album, "Was A Friend" and "Blues

In Bob Minor" come to mind.

RW: It's a generation thing I think. I'm just about a year older

than people who were brought up on the closed hi-hat concept of

timekeeping. I come from the Kenny Clarke ride cymbal era. It's

not that I'm a jazz player, but to me that seems to be the natural

feel for the kit, and I'm a very top-of-the-kit person. I don't really

play "rock 'n' roll"—I don't play "rock" anyway. I like to roll

around my tunes rather than rock.

I also particularly like the jazz 4/4, which is of course a 12/8. It

just seems to me you can sort of imply the triplets with the ride

cymbal in a very organic way, and with a very light touch. One of

my favorite rhythm sections was Dannie Richmond with Charles

Mingus. I was very impressed with the way they would sort of

tug against each other. I don't always use that feel, but on

"September The Ninth" on this album the bass and drums are sort

of pushing and pulling against each other.

AB: You also seem to enjoy playing with the snares off.

RW: Oh, yeah. I did a whole LP with the snares off, which was

the second Matching Mole one, Little Red Record. There are

ways of getting a cutting edge without the snares on. I really like

that slightly hollow sound. There are drummers I used to like, like

Ed Blackwell, all of whose drums sounded like toms. And even

now, on this record, I have the snare kind of floppy and rattly,

like Max Roach. In R&B and other styles, an extremely tight

snare is perfect. But not for me. I like an organic, grubby sort of sound.

AB: A long time ago in an interview you made mention of "submerging yourself in the work of learning to play three or four

drums." You have always had a relatively small kit, even with

Soft Machine...

RW: It's even smaller now! [laughs] All I'm really using now is

a snare and two cymbals, with a few little toy ones for the odd

"psh."

I like the gradations of sounds you can get on one drum rather

than always having sudden steps from drum to drum. It just

seems to be more organic than the rock thing. I really departed

from the rock thing, where you have this: [sings descending

notes]. I just like the sounds to merge into each other more. My

favorite drummer was Elvin Jones, and the thing about him that

really impressed me was that nearly every drum was almost tuned

the same.

It's the same with cymbals. I'd rather play a different part of a

good cymbal than have like eight cymbals up and only hit the same

place on each one. It's not intimate enough for me. To me, each

cymbal and drum is a complex instrument in its own right. And of

course it's a physical thing now. I can't reach out all over the

place; I'm quite liable to fall over, [laughs] So I like my kit close to

my body and tight and everything within very easy reach. That also

concentrates the mind.

AB: Do you think there is some connection to your lyrics and your

drumming style? You've made mention in the past of a conscious

decision to make the lyrics simpler and more conversational. Your

drumming has taken on a similar kind of evolution.

RW: Actually, I've never really thought of that comparison before.

I'll have to think about that; you may be right. I should point out,

though, that when I'm talking about music, everything seems more

deliberate than it actually is. When you are actually playing, you

are acting on instinct. You do a lot of calculating before you play,

and maybe after you play, but not while you are doing it. I don't

always know what I've done till I sit and think about it. Actually,

more and more, I've discarded every theory that I ever had about

what things ought to be like—even the thought that they've got to

be different. I'll use a common device just as happily as an unusual

one. All I think now is, "Does it feel alive; does it feel right?"

It's like when drummers are worried about their personality

coming through their playing. I don't think you have to think about

that. Being deliberately eccentric is as silly as being deliberately

conformist. If you just get comfortable, then your natural characteristics will come through. We are all unique without trying, as

anyone who has studied fingerprints or voiceprints will tell you.

AB: If you can call it this, one happy result of your not being able

to play a traditional trap set is a sort of elimination of the sound of

a drumset on your albums. When most drummers sit behind a kit,

they seem obliged to have to make noise with every limb.

RW: People do like to wiggle all four limbs at least once every

four seconds; I've noticed that. Actually, I don't think like a drummer really, or a singer, or any of these things. I'm thinking like a

composer. That may sound a bit pompous, but that's the best word

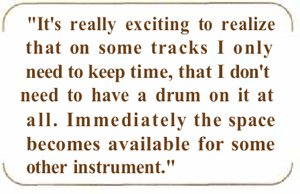

for it. I'm just trying to think about what the music needs. It's really exciting to realize that on some tracks I only need to keep time,

that I don't need to have a drum on it at all. It's amazing what you

can leave out, because immediately the space becomes available

for some other instrument. Everybody is in the rhythm section in

the end—not just the drummer. You won't fall down a great vacuum cavity if you stop using a limb temporarily.

AB: If you try that in rehearsal, you're liable to have the rest of the

band look at you like, "Well, why aren't you playing the whole

kit?"

RW: Right. Very often the difference between an amateur and a

professional musician is that the amateur is playing and the professional is listening. That's really the job. That's another reason I like

the translucence of the cymbal sound, because you can hear right

through it. It's important for me to be able to do that. The real problem I had after my accident was not losing the bass drum, because

as I get older my tastes get more old-fashioned, and I really don't

need that bass drum thing very often. But I did have trouble not

having a hi-hat. Listening to Billy Higgins playing and realizing

that he was squeezing the hi-hat with such a light touch led me to

think, I'll just go one step further and fantasize about playing the hi-

hat, and my body will kind of move with that.

AB: I'd like to go back in time a bit. You were lucky enough to

grow up in a home where you were encouraged to listen to music

that a lot of your peers probably never even knew existed.

RW: I was very lucky. For one thing, a lodger came to stay at our

house once whose name is George Niedorf. I think he had taught at

Valley Drum City in California and had run clinics with Joe

Morello. But his favorite was Philly Joe Jones, and he used to teach

me to listen—not to drummers, but to rhythm sections. That was

very, very useful to me. So I used to listen to a lot of things, like

Jimmy Cobb with Miles Davis. My older brother had a terrific

record collection, so that was perhaps why my tastes were a bit

more old-fashioned than some of my contemporaries'. I mean, at

school most of my friends were listening to the Everly Brothers. I just liked my brother's records more than theirs—it's as simple as

that.

AB: So by the time Daevid Allan [sic] came along, also as a lodger at

your parents' house, you two were listening to the same sorts of

things.

RW: He had a lot of the same records as my brother. Even before

then, though, my father had listened to twentieth-century classical

music a great deal—not extremely avant-garde, but certainly

Prokofiev and Benjamin Britten and so on. So I got used to kind of

dense, twentieth-century harmonic ideas. I never had any problem

with what people called "discord." There's no such thing; it's just

conditioning as far as I can see.

It was only later that I discovered pop music. I didn't understand

it at all at first. When I heard the Beatles I thought Ringo Starr was

just so banal. Now I can see what a perfect drummer he was. But it

took me years. The people that are called "avant-garde," I hear it

straight away. [laughs]

AB: In the mid '60s, audiences were becoming open to more out

stuff. The timing seemed pretty good for Soft Machine.

RW: I think we would have been better off a couple of years later.

We had some pretty rough rides with audiences, I can tell you. I

think I had this need to kind of lose the beat and find it again.

People found that very unnerving—including a lot of musicians I

played with! But sometimes I just like to stop playing. Dannie

Richmond used to do that quite a lot with Charles Mingus. There

would be whole sections where he would just, BANG, stop, the

band would carry on, and he'd come back in a chorus later. But that

was because Mingus told him to. Nobody told me to.

AB: You've said that touring with the Jimi Hendrix Experience was

positive for the group, musically at least.

RW: First of all, they were encouraging personally. They didn't

pull rank, which headliner groups can do. Second, Hendrix very

deliberately allowed Mitch Mitchell a lot of space to create drum

parts and to improvise. And they were doing it, not in front of tiny

jazz club audiences or avant-garde elite, but stadiums full of rock

fans—and they were getting away with it! And I realized that if you

do something with authority, as if you mean it, people will go with

that.

AB: Soft Machine and Pink Floyd have some common history.

Nick Mason, the drummer in Floyd, almost seems like your stylistic

opposite, yet you've worked together a few times.

RW: The Floyds were always very helpful to us. When I was working on Rock Bottom I was taking the responsibility for more than I

had taken on before. I just thought it would be great to have the ear

of someone else who wasn't in the middle of it, who really had a lot

of experience working in studios and making things sound right.

Nick drummed in order to make the piece of music sound right, not

in order to show off. He would just gently increase or decrease the

pressure throughout the song where appropriate. I felt that sense of

space and structure could help me in the studio, and I was right. He

was extremely helpful.

AB: The drummer on Rock Bottom is Laurie Allan, who American

audiences might not be familiar with.

RW: When it came time to do my first record where I couldn't really play the kit, Laurie was the first person I thought of. He was part

of the London scene and worked quite a lot with some show bands

and various free-jazz groups, but he understood rock music as well.

I felt in tune with him because of that. I also really liked his sound

and felt a real kinship with him, and that makes a difference.

Without friendship and companionship it's just a cold exercise.

Cleverness is not enough.

AB: You and the other members of Soft Machine worked on [Pink

Floyd founder] Syd Barren's first solo album. That must have been

quite a task, since his behavior had become quite erratic by that

point.

RW: I was actually very touched that he asked us. People say, "Are

you upset you weren't given credit on the record?" But I think he

left our names off out of kindness, [laughs] We went into the studio

and he was virtually mute. He just played us the songs that he had

recorded, and they were quite difficult in the sense that there was

hardly any sort of steady, regular time going through them. They

were structured around the words, which were not in any kind of

regular meter.

We rehearsed the songs a little and then were ready to record

them, at which time he said, "Right, that's it. Thank you very

much." So those initial takes became a few tracks of The Madcap

Laughs. But I think it was a wonderful record, and today I can see

exactly why he wanted to leave it as this clumsy searching sound.

He didn't want a smooth thing. I enjoyed the experience very much,

and I liked him. All the Floyd were very nice people.

AB: It sounds like his ideas were more intentional than people

assume.

RW: If you look at other art forms—like the paintings of Max

Ernst or the dadaists or early surrealists—you see that there's nothing unusually eccentric about people like Syd Barrett. I myself was

brought up as much with painters as musicians. Syd didn't strike me

as particularly eccentric; he struck me as a perfectly normal and

sensible songwriter—which maybe says something about me that I

don't want to know!

But I do think that we are not here to please the structures in

music, or in life. The structures are there where and when we need

them to help us out of the chaos if we are lost. But they shouldn't be

our masters. I think when any idiom sort of petrifies, it is precisely

because the structures have taken over from the impulses that have

set them up.

AB: You've mentioned being influenced by visual artists, but are

there any particular musicians you've been into lately?

RW: Some of the things I've been listening to include a Japanese

group called Ground Zero, who do remixes and sampling and

things, but not as dance music. I also listen to a lot of the great

American standards—Gershwin, Cole Porter. And I've been listening to an old singer named Jimmy Scott a lot, as well as a record

that Linda Ronstadt did with Nelson Riddle, which was done with a

lot of respect.

People sometimes listen to my lyrics and think, "Oh, he must be

really anti-American," but that's not the case at all. It's just that I

find all imperialist governments a pain in the bum. But it's not the

people's fault; don't blame the culture. The fact is that something

extraordinary happened in American culture in the last hundred

years or so: Diverse immigrant groups came together and reinvented their identities alongside each other in ways that have just been

fantastic. When you think of Miles Davis and Gil Evans doing

Porgy And Bess, and you think of the history of the ideas on a

record like that—from black Americans to Jewish Americans to

goodness knows who else...that's really the area that interests me

most at the moment.

I don't feel any obligation to keep up to date. I agree with Byron,

who said, "Every time somebody tells me about a wonderful new

book, I go out and buy an old one."

AB: There does always seem to be old stuff to discover.

RW: That's right. In fact, I didn't really appreciate Bob Dylan so

much at the time, although Hendrix used to say how great he was.

But since then I've liked him more and more, which is why I've got

that little Bob Dylan tribute on the record, "Blues In Bob Minor."

AB: I guess you haven't heard from him on it yet.

RW: No. I just hope that he will realize that I'm "Bob Minor" and

he's "Bob Major"!

Thanks to John Godlewski from Absolute Vinyl in Montclair, New

Jersey for invaluable research help on this article.

|