| |

|

|

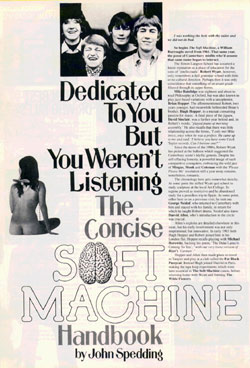

Dedicated

To You But You Weren't Listening - The Concise SOFT MACHINE

Handbook - Strange Things - Volume 1 * Number 6 - Summer

1989 Dedicated

To You But You Weren't Listening - The Concise SOFT MACHINE

Handbook - Strange Things - Volume 1 * Number 6 - Summer

1989

THE CONCISE SOFT

MACHINE HANDBOOK

by John Speeding

I was working the hole

with the sailor and we did not do bad.

So begins The Soft Machine, a William Burroughs

novel from 1961. That same year, the posse of Canterbury

misfits who'd assume that same name began to interact.

The Simon Langton School has assumed a latent reputation

as a place of education for the sons of 'intellectuals'.

Robert Wyatt, however, only remembers a dull grammar

school with little or no cultural direction. Perhaps then

it was only coincidence that something of an avant-grade

filtered through its upper forms.

Mike Ratelidge was eighteen and about to read Philosophy

at Oxford, but was also known to play jazz-based variations

with a saxophonist, Brian Hopper. The afforementioned

Robert, two years younger, had meanwhile befriended Brian's

brother, Hugh Hopper, in a mutual consuming passion

for music. A final piece of the jigsaw, David Sinclair,

was a further year behind and, in Robert's words, "played

piano at morning assembly." He also recalls that

there was little relationship across the forms, "I

only met Mike twice, once when he was a prefect. He came

up to me and said, 'I believe you have some Cecil Taylor

records. Can I borrow one?'"

Since the dawn of the 1980s, Robert Wyatt has picked at

the balloon which suggested the Canterbury scene's idyllic

genesis. Despite his self-effacing honesty, a powerful image

of such comparitive youngsters, embracing the wild jazz

of Mingus, Monk and Coleman with the

'Please Please Me' revelation still a year away remains,

nonetheless, romantic.

The chronology here gets somewhat sketchy. At some point

the stilled Wyatt quit school to study sculpture at the

local Art College. Its regime proved as restrictive and

he abandoned study for a penniless trip to Spain. At some

point, either here or on a

previous visit, he met one George Neidof, who returned

to Canterbury with him and stayed with his family, in return

for which he taught Robert drums. Neidof also knew Daevid

Allen, who's introduction to the circle was crucial.

Allen's exploits are detailed elsewhere in this issue, but

his early involvement was not only inspirational, but innovative.

In early 1963 both Hugh Hopper and Robert joined him in

his London flat. Hopper recalls playing with Michael

Horowitz, backing his poem, 'The Dalai Lama Is Coming

To Tea', "with our very loose version of Bizet's

'Carmen'."

Hopper and Allen then made plans to travel to Tangier and

play at a club called the Fat Black Pussycat. Instead

Hugh joined Daevid in Paris, making the tape loop experiments

which were later essential to The Soft Machine canon,

before returning home with Wyatt and forming The Wilde

Flowers.

Here they were joined by the elder Hopper, Brian, Richard

Sinclair and Kevin Ayers. Mutual fashion rather than a common

education had brought Kevin into the group, who's debut

gig was at Whitstable's Bear and Key Hotel. "They

try for an Indian

influence," noted the 'Canterbury Gazette',

"but their Rolling Stones haircuts make the

fans go crazy." The Wilde Flowers set was British

R&B, some Beatles and some originals, a flavour of which

was caught on a brief 1965 demo. recorded at the unlikely

Wout Steenhuis studio. The groups leafs its way through

two covers. Chuck Berry's 'Almost Grown and

Mose Allison's reading of 'Parchman Farm',

alongside two originals, Hugh Hopper's reflective 'Memories'

and Kevin's rumbustuous 'She's Gone'.

In common with their future aggregations, The Wilde Flowers

were notoriously unstable. Ayers left, a new guitarist,

Graham Flight, appeared and vanished and Richard

Sinclair traded rhythm guitar for college. Robert stopped

drumming in favour of permanent vocals. Richard Coughlan

replaced him at the kit. and one Pye Hastings latterly

joined on lead. By 1966 The Wilde Flowers were altogether

smoother: they entered competitions both for Melody Maker

and Radio Caroline, winning the latter with a heady

mix of 'Sunny', 'Papa's Got A Brand New Bag'

and 'You Put A Spell On Me'. This line-up, however,

crumbled around October 1966 with the departure of Robert

Wyatt. (Hugh Hopper quit some five months later, the rest

then added David Sinclair and became Caravan.)

Wyatt, Ayers and Daevid Allen had reestablished contact

and a frustrated Mike Ratelidge had left university. The

new group flirted with several names, another William Burrough's

title, Nova Express, was considered, but Soft

Machine was finally selected with Alien telephoning

the author for permission and a blessing.

Following a disastrous opening at London's Zebra Club.

Daevid's connections with the fledgling London Underground;

John Hopkins and the Indica gang, provided

the Softs with their spot at the party to launch

'International Times' and subsequent residency at

the hallowed UFO. On these early dates the group

was supplemented by Larry Nolan, an American guitarist

who vanished as mysteriously as he appeared, and by Mark

Boyle's evocative light show, which formed the perfect

counterpoint to a collective increasing it's weirdo quotient.

Pete Frame recalls their appearance at The 14

Hour Technicolor Dream in April 1967.

"Robert Wyatt huffing and puffing and singing from

his drum stool, Kevin Ayers with rouge on his cheeks and

u black cowboy hat surrounded by a huge pair of glider's

wings and Daevid Alien with a miner's helmet (light switched

on) and a fixed maniac stare."

|

|

In the meantime Kevin had tried to

place some of his songs with The (New) Animals, an

effort which brought the Softs into contact with

Mike Jeffries and Chas Chandler. The former

became their manager, the latter their early producer, responsible

for the topside of the group's first single. 'Love makes

Sweet Music'.

Written by Kevin at his commercial best, it moved with an

effortless, magical ease, both confident and irresistible.

Its coupling. 'Feelin Reelin' Squeelin", was

produced by the itinerant Kim Fowley and reflected The

Soft Machine's wilder conceptions with Ayers' maniacal

growl and Allen's liquid guitar.

Despite soaring to the dizzy heights of No.28 on the Radio

London chart, 'Love Makes Sweet Music' made little

impression and Polydor dropped any option. A series

of demos were subsequently cut at De Lane Lea studios,

with Giorgio Gomelsky producing. These tapes have

cropped up in various guises, most recently as Jet

Propelled Photographs. Although certainly rough

and ramshackle, they mix missed notes with a raw ambition

and are

genuinely engaging.

The songs are split between Robert, Kevin and Hugh Hopper,

now on the fringe of the group as their roadie. Both 'She's

Gone' and 'Memories' are resurrected from The

Wilde Flowers tape. The latter is as haunting as the

group from this era could be, while

other highlights appear in the splendid 'I Should've

Known' (freak-out via the 'Shotgun riff) and

Robert's melancholic 'That's How Much I Needed To Know',

the melody of which would, alongside that of 'You Don't

Remember', reappear, shorn of its adolesent lyric, on

Third's 'Moon In June'. Indeed much of the

collection would surface elsewhere; Kevin's 'Jet Propelled

Photograph' became 'Shooting At The Moon', while

'Save Yourself" and 'I Should Have Know'

were recut for the first official album,the former relatively

intact, its counterpart, however, was somewhat remodelled

and became 'Why Am I So Short'.

The boys then recorded a third 'She's Gone', this

time with Joe Boyd producing. Scheduled as a single,

and featuring Bill Burroughs on "barely

audible aphorism", it was never released as such,

although it was subsequently aired on Triple Echo,

a 1977

retrospective. 'She's Gone' also marked the end

of Daevid Allen's involvement, his de facto deportation

reduced the line-up to a trio and increased the "jungle

warfare" (Allen) simmering within the group.

1967 ended with the Christmas

On Earth concert, 1968 began with a marathon American

tour, supporting Eire Apparent and the Jimi Hendrix

Experience. Each was a part of the Jeffries stable,

indeed Hendrix had some rhythm guitar to an early, rejected

'Love Makes Sweet Music' while Ayers, Wyatt and Alien

sang at the back of a similarly canned 'Stone Free'.

At least that's the legend. And while we're weaving webs,

don't forget Hendrix makes a splintering, but brief, appearance

on Eire Apparent's only album. (UK pressings only!) The

U.S. tour lasted six months, and was gruelling. In an effort

to diffuse the instrumental strain, guitarist Andy Summers

was briefly drafted in, but he switched instead to The

New Animals. "Nightmare-ish" was how

Wyatt described one particular date at Madison Square

Gardens, where the touring party was supplemented by

Albert King, The Chambers Brothers and Big

Brother and the Holding Company. The marathon closed

at the Hollywood Bowl and an exhausted group was

flown back to New York to cut their debut album.

Ostensibly produced by Tom Wilson, ("We'd

do a take," remembers Wyatt, "go hack into

the control room, and he'd he on the 'phone to some girl.").

the set is a triumph of imagination over adversity, and

captures many of The Soft's most thrilling moments.

In 'So Boot If At All' the group capture the essence

of Underground improvisation, and match the cascading genius

of 'Interstellar Overdrive'. Another Hugh Hopper

revival. 'Hope For Happiness', provides an ideal,

stylistic introduction, while the rest of the record matches

Kevin's angular eccentricity, the studied seriousness of

Ratelidge, and Robert's heartfelt passion.

On completion, The Soft Machine disintegrated. Wyatt

stayed behind in New York, completing 'Moon In June'

from his diary cum scrapbook, Ayers made for Ibiza and Mike

flew back to London to compose. By winter Robert was in

L.A., writing and recording

enough for two demo albums, one featuring the full 'Moon

In June', the other fragments of older Hugh Hopper material,

rearranged and given new lyrics, much of which appeared

on their next album.

In the meantime Probe had released The Soft Machine.

It became a cult success, and a demand grew for some kind

of group to tour behind it. Wyatt and Ratelidge were, somewhat

guardedly, reunited, but Kevin Ayers, who's quirky compositions

were at odds with the studious keyboard wizard, was now

uninterested and had sold his bass to Mitch Mitchell.

Hugh Hopper provided the natural replacement and a reconstituted

Soft Machine began rehearsing almost immediately.

They openned with a blow at The Roundhouse with Andy

Summers and Zoot Money, before appearing, properly, in public

at The Albert Hall alongside Hendrix and the Traffic

substitute, Mason, Wood, Capaldi and Frog. A second

album, Volume Two, was recorded over February and

March 1969, and although another wonderful work, the divisions

within the group seemed wider than ever. A scan of the titles

reflects the gap: "Thank You Pierrot Lunaire'.

'Have You Ever Been Green'' (the surreal Wyatt),

against the formal eccentricity of 'Fire Engine Passing

With Bells Clanging' and 'A Door Opens And Closes',

two of Mike Ratelidge's moments. Although inevitably distanced

from The Soft Machine's paisley patterns, the new

collection boasted a real maturity, and a sound refined

to suit a studio environment.

|

|

Brian Hopper had re-emerged

on the album to add both soprano and tenor sax, an indication

of the group's future development. Between October and the

end of 1969, the trio was augmented by a radical horn section;

Lyn Dobson (flute & soprano sax), Elton Dean (alto sax & saxello), Nick Evans (trombone) and

Marc Charig (cornet). Their collective pedigree included

Manfred Mann, Keith Tippet and Bluesology,

but the experiment proved too expensive and was dropped.

Although the septet would not offically record as such,

a session was cut for Peel's 'Top Gear' that

November. 'Esther's Nosejob' and 'the 'Mousetrap' /'

Noisette' /' Backwards' / Mousetrap Reprise' workout

thus gave a glimpse into a somewhat unrealised potential,

hut also showed the eclipse of the drummer's own ideosyncratic

direction. The session was also revived on Triple Echo,

along with two corresponding pieces. The first featured

the basic trio on an inspired reading of Robert's 'Moon

In June', the lyric of which was specially written for

the occasion to include references to the programme, BBC

tea, Caravan and Pink Floyd. It was, and is,

quite simply, a masterpiece.

The remaining session was from May 1970, and contained three

Ratelidge compositions, 'Slightly All The Time',

'Out Bloody Rageous' and 'Eamonn Andrews',

the first two of which appeared (in different forms) on

Third, the Soft Machine's next album.

Although it featured several extra musicians, including

Dobson and Evans, Elton Dean remained the only permanent

addition to the Wyatt/Hopper/Ratelidge triumvurate. A double

set spread over four basic pieces, the estrangement between

Robert and the rest was near complete. They hated 'Moon

In June' and initially refused to play on it. Wyatt

added his own bass and keyboards and although both Hugh

and Mike would latterly play a minor role, it is, obstensibly,

a solo effort. The ultimate irony, perhaps, was that Robert

admired what the rest were attempting, especially Hopper.

"(Hugh) was the most creative. Excellent though

Mike's things were. they could have been written by Herbie

Hancock or Wayne Shorter. It was putting us on the fringes

of other people's worlds rather than at the centre of our

own. To he to, say. Tony Williams, what The Stones were

to Muddy Waters, was not really my ambition."

The last act of defiance by what was recognisably the 'old'

Soft Machine came in August and their performance

at the Albert Hall's Pop Promenade. Sandwiched between the

respectability of an archaic music establishment was a somewhat

rough-hewn set, evenby the group's own standards, but one

now captured on a new-ish release, Live At The Proms

1970. Whatever the contemporary controversy, the invitation

to appear cemented the ascendant seriousness, as the more

formal programme suggested.

Now somewhat alone, Wyatt embarked on a solo album, the

punning End Of An Ear. Those expecting a further

stream-of-consciousness were caught somewhat surprised,

this was a sometimes impenetrable mix, but one which allowed

an important breathing space. It was, in many ways, the

instrumental interludes of the early Soft Machine,

but without the songs or hooks to 'bookend' them together.

Mark Charig and EIton Dean provided the woodwind, David

Sinclair the organ, while Robert drummed (naturally), sang

a little and began his experimentation with keyboards. If

The End Of An Ear was autobiographical, it was in

the titles; 'To Saintly Bridget' (Bridget St.John),

'To Caravan And Brother Jim', 'To 0z Alien Daevid

And Gilli', although the sometimes furious stew

which spilled out in places doubtlessly reflected the confusion

of the times.

|

|

Wyatt indeed took a sabbatical and

toured with Kevin Ayers and the Whole World before

returning to The Soft Machine's fold for Fourth,

a dour, paired-down version of its predecessors. His percussion

aside, Robert's contribution is minimal, and a suggestion,

to manager Scan Murphy, that he might like to try something

else, was eagerly seized upon by Hopper and Ratelidge. Wyatt

was fired in September 1971, and with him went the heart,

soul and humour of a group, once excellent, now doomed to

a future of cold mathematics.

Heartfelt thanks are due to Ian McDonald, Pete

Frame and John Platt for providing the original

detective work and several of the above quotes. Kevin

Ayers' subsequent erratic, but more often than not,

inspired career can he found elsewhere in this issue, while

What happened to Robert Wyatt will he divulged in a forthcoming

volume of this magazine.

|