| |

|

|

There's

a Wyatt going on - The Wire Issue 91 - September 1991 There's

a Wyatt going on - The Wire Issue 91 - September 1991

|

|

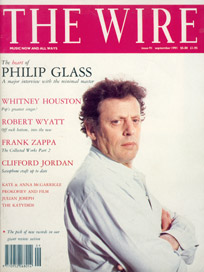

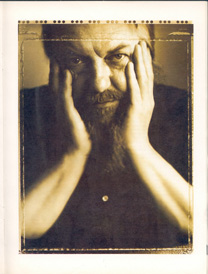

THERE'S A WYATT

GOING ON

Robert Wyatt, that is. The art-rock artisan

of Soft Machine and Rock Bottom is back with

a brand-new record. Ben Watson meets the unmatched

mole of subversive pop. Photo by Michael Heffernan.

Robert Wyatt 's muse is back on-line. His new release, Dondestan,

is a telling and sensual as anything he has produced over

the last three decades. After a series of politically-oriented-projects

- the SWAPO benefit with Jerry Dammers, "Winds Of Change",

Elvis Costello's "Shipbuilding" - he has returned

to the music he "hears in his head", a strange

but effective mix of multitracked vocals and electric keyboards.

Drummer in The Soft Machine (the band, that, along with

Pink Floyd, epitomised late-60s underground rock in London),

Wyatt's second band Matching Mole was scuppered in 1973

by a fall that broke his back. Paraplegic and wheelchair

bound, he had to do a musical rethink: jazz and rock drummers

require legs. He found his voice could be an instrument.

In 1974 he released Rock Bottom, a masterpiece which

many interpreted as a commentary on his condition. Such

biographical interpretations are limiting. Being unable

to stir up bass drum and hi-hat bombast may explain its

calm, but the music was also an excellent critique of the

techno-pomp that progressive rock had become. Its domestic

quietism showed up commercialized virtuosity (Yes, ELP,

Genesis, Chick Corea) as effectively as the garage virtues

of punk did three years later. It had the haunting stillness

of Claude Debussy or Marvin Gaye: power through poignancy.

Dondestan does it again. How come?

"I got more into Dondestan than anything since

Rock Bottom. The organ I used on Rock Bottom

is called a Riviera. Alfie got it for us, it cost about

ten bob in an Italian toy shop. It's a three or four-octave

toy organ and I broke it in the late-70s and I thought,

that's it - it's symbolic. But since coming here to Lincolnshire,

Alfie said, Why don't you get it mended, and I've got it

mended. It's one of the reasons I was able to pick up from

Rock Bottom. You will hear the same sounds - it's

exactly the same organ and they don't make it anymore.

It was not just the Riviera. Wyatt has a healthy horror

of "setting texts", aware of the proper gel between

word and note that characterizes authentic song. A Kip Hanrahan

project on Paul Haines (lyricist for Escalator Over The

Hill) led to a track he was pleased with. The project

remains unreleased - unfortunate, because the other contributions

(by, among others, Roswell Rudd, Evan Parker and Derek Bailey)

sound intriguing too - but Wyatt learned that other people's

texts could be a stimulus.

Robert Wyatt's partner, Alfreda Benge, had written a book

of poems called Out Of Season when they were both

wintering in Catalonia in the mid-80s.

"When you become very familiar with something, it becomes

songlike in the head. I can't make a rule, but that's how

it happened. The poems were not written to be sung and therefore

they hadn't got the structures I fall into."

"The Sight Of The Wind" conveys what Wyatt calls

"a sense of the unfixableness of things". Robert

used a characteristically eccentric device.

"I used heavy breathing as a rhythm track which I haven't

done since Rock Bottom, because you just get a dip

and a rise rather than a punched-out beat. It was in seven,

so it wouldn't settle."

Wyatt is quick to dissociate himself from the fusion groups

who play in 7/4 in order to be "more complex".

"I'm not one for fancy time signatures - if you get

too clever with time signatures it sounds like the Newsnight theme - but sometimes you do want an unbalanced shift. You

can do anything in 4/4, look at Monk. 4/4 isn't just 4/4

anyway, it's 12/8. All any complex time signature really

is, is binary, either twos or ones in various combinations

- so no complex time signature is any more complex than

a simple one."

There is a wonderful section in "Left On Man"

where Wyatt choruses "oversimplify, reduce, oversimplify".

This guying of the conventional refutation of Marxism sounds

for all the world like Marvin Gaye singing "dance with

me baby" on I Want You.

"Marvin Gaye is very close to my heart.

There's something translucent about his textures, it's like

a sea with various layers and undertones. But actually that

comes off Groupa Irakere. They have this Cuban thing where

a couple of blokes put down their instruments and do a chorus

thing [sings and taps a clave rhythm]. I thought, it's so

nice when they do that, why aren't I a group, why can't

I put down my trumpets and trombones and do that as well?"

"Lisp Service" is a reply to Billy Joel's apology

for US foreign policy, whose video appeased (supposedly)

longforgotten wars by combining every famous image of American

military atrocity - Hiroshima, napalm fire, summary execution

- with a chorus that blithely claimed "We didn't

start the fire/It's been burning since the world began".

"'We Didn't Start The Fire' worried me, I thought,

Oh you smug git - yes you fucking did! If you're talking

about 'we' I can talk about 'you'. I don't often listen

to words, but he was saying, Listen to me, I've got something

serious to say, and I thought - you'd better have!"

Hugh Hopper's rousing melody gives "Lisp Service"

an eruptive force after the dreamy chant that precedes it.

Wyatt's own tunes have startling intervals and pungent harmonies

lacking in most pop music. Born in 1945, you might expect

him to be a blues boomer. Actually it has always been jazz

that fired him, ever since his father led him onto Fats

Waller. He hears differently.

"My father used to play Shostakovitch, Hindemith, Bartok,

and my mother played Monteverdi. I didn't hear much rock'n'roll

and I never liked it. My dad introduced me to jazz, I think

he'd seen Stormy Weather as a younger man. I thought

it was so wonderful that it took over my ears completely.

My dad got quite alarmed because I stopped playing the Bartok.

That was it really, I was in love and I've remained so."

Just now, as Natalie Cole's revival of "Unforgettable"

is bringing a startling shot of harmonic surprise to the

charts - King Cole's piano intro suddenly unleashing chords

synthipop producers have all forgotten - it is interesting

to hear Wyatt point out a different direction to blues,

rock and the pop norms of the 90s.

"I think maybe, being brought up on Hindemith and so

on, I just wanted that bit extra out of the chords, the

harmonies. When I did like singers it would be where there

would be harmonic stuff going on which you don't get on

a blues record - Ray Charles is so sophisticated harmonically.

That I could really deal with - it was the keyboard end

rather the guitar end."

Robert listens hard to music as music: his observations

have a spark lacking in either academic received wisdom

or self-serving biztalk. The disinterest in guitar, for

example, did not preclude appreciation of Jimi Hendrix,

whom the Soft Machine supported for a year: "so beautiful

every bloody time".

Wyatt is remarkably successful in using "world-music"

aspects - Kurdish lilts and Ouspecki rhythms litter Dondestan,

but he feels that any jazz enthusiast is already well prepared.

"It's like clothes - they have to fit. I don't have

a sense of the exotic. If you are a jazz fan you're used

to having people whose ancestors were African in your room,

so the whole concept of 'world music' doesn't mean that

much to you anyway."

His new enthusiasm is rap (a musical development that has

turned people ten years his junior into nostalgia freaks).

"When you speak words it's atonal music and drumming

is mostly atonal. Rap is very liberating, just getting the

rhythms and rhymes - that's where the music is, not in the

notes. It means that apart from the bass line, which can

be quite conventional, the stuff they can do - the little

textures and fiddly bits around the edge and the noises

they are making - where is that coming from? How did they

get that in there? How did they get so much in there?

How do they get so much in there clearly between

those two beats? Stunning stuff!"

New enthusiasms aside, he keeps returning to bebop.

"It's like cubism - obstinately unyielding and compressed,

not what they call user-friendly. Or like pemmican,

concentrated food Arctic explorers are. A taste of that

and anything else is flaccid. I can see, outside it, the

architecture isn't inviting, the space doesn't seem to be

there to sit down and make yourself comfortable - but once

you learn your way around in there it's utterly addictive."

When he talks about his upbringing, Wyatt's voice grows

quiet, and it is important to remember the battles of his

generation, a period when all black music was dismissed

as trivial entertainment, to be patronised by those who

knew classical music. His manner is so disarmingly unpretentious,

that it was only when transcribing his words that I realized

quite how angry they were.

"If you sing in a choir at school... we did Schubert,

so I remember a bit about him. We were told how to sing

vowels. We were told that the trouble with English was these

short vowels - we can't sing them, you can't hold a note

on them, so for the following vowels this is how to sing

them, you've got to break them down: 'ow' goes 'aa-ooo'

and you have to decide when to go from 'aa' to 'ooo'; 'i'

goes 'aa-eee'; and if you think how posh singers sing, they

sing 'through the naa-eet [night]' because they never sing

'i'. Which means that you get this really churchy mannerism

that only has one connotation. If I'd been stuck in legitimate

singing... I'm really grateful to all the musics we've been

discussing for not being bound by rules like that."

| |

selected discography

The Soft Machine - The Soft Machine (Probe)

1968

The Soft Machine - Volume Two (Probe SPB1002)

1969

The Soft Machine - Third (CBS66246) 1970

The Soft Machine - 4 (CBS 64280) 1970

The Soft Machine - Triple Echo (Harvest SHTW800)

triple 1967-76

Robert Wyatt - End Of An Ear (CBS) 1971

Robert Wyatt - Matching Mole (CBS)

Robert Wyatt - Little Red Record (CBS 65260)

1972

Robert Wyatt - I'm a Believer (Virgin VS114)

7" 1974

Robert Wyatt - Rock Bottom (Virgin V2017)

1974

Robert Wyatt - Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard

(Virgin V2034)

Jan Steele/John Cage - Voices And Instruments

(Island/Obscure 5) 1976

Robert Wyatt - Animal Film Soundtrack (Rough

Trade ROUGH40) 1981

Robert Wyatt - Nothing Can Stop Us (Rough

Trade ROUGH35) 1980-2

Robert Wyatt - Shipbuilding (Rough Trade

RTT115) 12" 1982

Robert Wyatt - Work In Progress (Rough Trade

RTT149) EP 1984

Robert Wyatt - The Age Of Self (TUC) 7"

1985

Robert Wyatt/SWAPO Singers - The Wind Of Change

(Rough Trade RTT168) 12" 1985

Robert Wyatt - Old Rotten Hat (Rough Trade

ROUGH69) 1985

Robert Wyatt - Dondestan (Rough Trade) 1991

|

|

|