| |

|

|

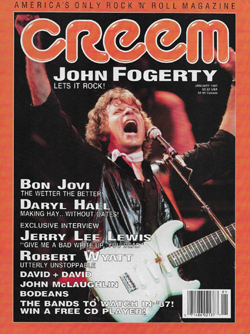

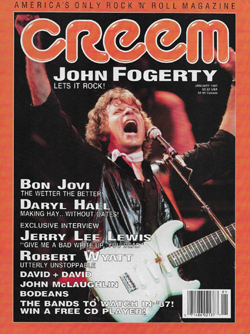

Things you should know about Robert Wyatt - Creem - January 1987 Things you should know about Robert Wyatt - Creem - January 1987

|

|

It's difficult to call it more than coincidence.

The driver hired to take me south of London, to the home of the person I'm to interview, spends an extraordinary amount of time telling me how apartheid is inherently good—how the black people "down there" can't quite take care of themselves yet, that they're extremely violent themselves, what are they complaining about? — and much more of that talk, talk I'm not used to hearing in England. I guess there's a lot of it.

The driver has no idea where we're going. In fact, he tells me, he's glad I speak English — "I thought you were an Italian bloke," says he. We get very close to the neighborhood we're seeking, find the proper street, and search the small row of townhouses for the address he's been given.

Robert Wyatt's house stands out among the rest on his block; it's the one with the large END APARTHEID! poster tacked onto the front door.

The driver pulls out a book he'd planned to read in the car while I was doing my interview. It's by Jackie Collins.

Inside the house are many more books. These books are by Marx, Engels, Lenin and others; they're about Latin America and Africa, about political and economic systems; other cultures. Robert Wyatt's wife, Alfie, tells me Robert will be ready for the interview in a few short moments. Would I like some coffee or tea? Oh, and there's no point in the driver waiting outside in his car; invite him to come in as well.

A man in a wheelchair enters the room. The interview takes place.

Later, the driver and I get back in the car. His first words, spoken in amazement: "That woman was a bleedin' communist, mate."

He's diplomatic when it comes to his reasons for leaving that pioneering band, though the back of his first solo album, 1970's The End Of An Ear, bears this intriguing self-description; "Out of work Pop Singer (Currently on drums with Soft Machine)." Wyatt wouldn't be hanging around with the band much longer after releasing it.

"It was sort of a 40-minute burst of frustration, in a way," says he.

Frustration with what?

"Well, I think a lot of drummers are neurotics. That's the sort of thing you used to get in jazz. Because the thing in jazz is, ‘This band's got four musicians and a drummer,' that sort of thing." He laughs again. "And there was always that feeling. I was, and have remained, virtually musically illiterate. And you sort of feel — I mean, they used to say to me, 'Why don't you learn to read music?' And I would say, my excuse was, 'So you can't write own what I've got to play.’

|

|

"But it was sort of feeble. I always felt on the defensive, you know? So from The End Of An Ear onwards, I started to go on the attack."

What does he remember most about the band?

"What I remember was, a very experimental era in the early '60s, when we were mucking about with tapes, and where there were no holds barred and stuff like that. And the early group live was an extremely open format, I think.

"And gradually, it stalled to narrow down, and became what you'd call a jazz-rock group. And I felt like the options were closing, that the possibilities were being cut off. Although also during that period, we all got to play much better. So it was odd, we got freer in terms of technique, but it seemed to hamper and predetermine what we actually did with it. We were much braver before we had any technique."

Does he think the band should've changed its name after he left?

"Oh, I don't know—in retrospect, they're welcome to it, you know? But I think we should all give it back to Bill Burroughs and forget the whole thing."

Wyatt next turned up in his own band, Matching Mole, in 1972. People that know tell me "Matching Mole" means "Soft Machine" in French, at least phonetically. In the band were friends, like David Sinclair, Phil Miller, Bill MacCormick and Dave McRae. The records were excellent, and much more experimental than the fifth and sixth Soft Machine albums, both wordless and Wyatt-less.

"It was really a necessity," remembers Wyatt. "I had to put something together. Because it's very difficult to find bands to work in. I mean, very often if you're a drummer or a singer, there's some opportunity to join this band or that band. But the particular way in which / like to operate—which is, you know, I might want to do songs, but I might want at least as much instrumental, and I might want to have a few very accessible pieces, and a few pieces where we try everything we can think of on them—there wasn't any band to join where you could do that in.

"So the only way was just to find some sympathetic friends and carry on. But people who, even if they didn't like you singing, didn't have the power to stop you."

Wyatt smiles at his exaggeration.

A second Matching Mole album would soon follow, Matching Mole's Little Red Record. It was stranger than the first. Robert Fripp produced it, and former Roxy Music pop star Brian Eno even played synthesizer on it. The band was beginning to develop its own very

charming personality.

And then Robert Wyatt's accident happened. A fall from building is what did it; he's been confined to a wheelchair ever since. For a drummer who favored using his bass drum and hi-hat, it couldn't be much worse. Yet after months in the hospital, Wyatt would emerge with what still stands as his masterpiece, 1974's Rock Bottom. From its very unusual cover, an illustration by Wyatt's wife Alfreda Benge, to its opening track "Sea Song" (which fans Tears For Fears recorded last year as a B-side), and its finale, "Little Red Robin Hood Hit The Road," Rock Bottom is one of the finest albums of the '70s.

"In a way," says Wyatt, "that was the easiest record I've ever had to make. It was the first record where you didn't have to spend half the time trying to carry the drum kit around all over the place." Again, he laughs. "Somebody else was the drummer - this was very liberating.

So there was less to think about. Because before, I'd been trying to get about drumming and the kit, and writing and arranging and organizing gigs, and singing and writing songs. So cutting it down to those last two, just concentrating on the bits I could handle, and leaving more to other people, was quite liberating.

"It was just because I wasn't in a group, and I wasn't having to organize that, and I wasn't having to worry about what four people were gonna eat that week, you know? I could concentrate on the music. Like I hadn't really been able to before. So it was...that was easy.

"And the thing is, there was a piano in the hospital as well, in their visitors' room—and there weren't many visitors. At least there weren't after / got near the piano. They stopped coming. And so when I got out of the hospital, I was really ready. Because I had to spend about seven months in the hospital, and the last two months I was already in the chair, just learning to get around."

Many fans of Wyatt's assume the bulk of Rock Bottom was written in the hospital while he recuperated; in fact, prior to the accident he'd been preparing for a third Matching Mole album. "People think it must've been written all afterwards, but in fact no, [the unrecorded Matching Mole LP] would've been something like that anyway."

After that came an actual hit single for Wyatt - a cover of "I'm A Believer," ironically — a non-hit follow-up, "Yesterday Man," and the Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard album. The latter was much more a collaborative effort that anything Wyatt had recorded previously; it's interesting and it's humorous, but it lacks the emotional bite of its predecessor. It was also the last Robert Wyatt album for several years.

The collaborations continued. He'd already done things on albums by Hatfield And The North and Henry Cow; soon his name appeared on works by Brian Eno, Phil Manzanera and many others. Most notable were the series of albums he recorded with Carla Bley and Mike Mantler; the best of the bunch is The Hapless Child, though Mantler's adaptation of the Harold Pinter play, Silence, featured the great Kevin Coyne and also deserves serious attention. Wyatt also popped up on a solo LP by Pink Floyd's Nick Mason (who'd produced Rock Bottom) called Fictitious Sports, which not incidentally consisted entirely of material written by Carla Bley.

But it took a very long time for Robert Wyatt to release his own records again.

After a long period of silence, you finally started issuing some singles. How did you decide on that material?

"Well, during the '70s, something happened to my feeling, being in the rock world. There seemed to be this consensus, which was that it was a new and semi-legitimate art form, and it was a sort of natural vehicle for new and rebellious ideas. And during the '70s, it became quite clear to me that what we were, as rock musicians, were in fact members of the establishment. That it was an establishment, and perhaps it always had been, ever since Elvis joined the Gl's. We thought we were kidding.

"But nevertheless, it became part of the big Western propaganda culture, all this stuff. And so really, I became interested in retrieving the idea of a sort of, if you like, disobedient music, where rebel poses had become so...sort of established, it's part of the whole rock 'n' roll circus.

|

|

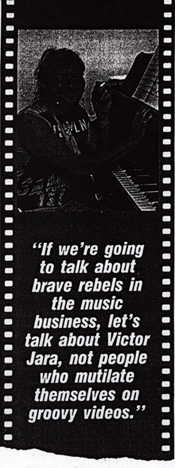

"You were getting to funny stages, where people who deliberately maimed themselves onstage were selling themselves as brave and courageous, whereas you had someone like Victor Jara in Chile, who because he sang for democracy in Chile, was tortured to death. If we're going to talk about brave rebels in the music business, let's talk about Victor Jara, not people who mutilate themselves on groovy videos.

"And I just wanted to—I started to see more and more of the world that was truly alienated by our establishment, that wasn't included in rock 'n' roll, really."

How did you see this? From reading? Films?

"I don't know, in any one particular way. I was very, very hit by the death of Mongezi Feza, the South African trumpet player who was the same age as me, and died at about 31 in the early '70s. And really, he died of old age and a broken heart at 31, as a South African exile who thought he'd escape to England and found that you don't escape racism that easily. He'd come to the country that invented apartheid to get away—and exported it—but that hadn't occurred to him.

"His death hit me very hard. Quite selfishly, I was very angry to have been deprived of a musician I really enjoyed working with. I started to think. You know, we're told in rock 'n' roll that this is the democratic art form, this is the art form where the inarticulate are allowed to speak. You know? All that stuff—this is where black and white and working class, this is how we...

"But in fact, because it was so proud of being that, all the people who were alienated from this whole cozy consensus, you can see them in stark relief around you. People who weren't included in this happy rebel party of rock 'n' roll. So in different ways, I wouldn't say there was one line going through everything I did—but I would say that was the kind of thought that was going through my mind when I chose songs."

The string of singles Wyatt released in the early '80s was stunning in variety, conception, and performance. If you'd like to hear them, you can; most are collected on Nothing Can Stop Us, issued here in September on Gramavision Records.

Listen to these songs. Notice that they all have one thing in common: they are songs of freedom. Thus from Chic's "At Last I Am Free" and Billie Holiday's "Strange Fruit" to songs by Violetta Para, Victor Jara and Pablo Milanos, Wyatt has put together as aural collage that, however unusual the sources, holds together better thematically than anything he'd recorded in his life.

Listen to Wyatt's version of "At Last I Am Free."

"I think it's a mistake in thinking the only music of rebellious significance, of revolutionary significance, is in music which is consciously so," says Wyatt. "In any piece of music, if you say, 'We exist and we're proud of existing, we wish to do well and flourish, like everyone else'—in certain societies, it has political connotations.

"At that time, people like Chic, were being dismissed. I mean, I know that Chic, when they were young, had been attracted by the Black Power movement like a lot of people, but decided that the best thing to do was just to try and 'make it.' But the way they did it at that time had no legitimacy within rock currency, because they were smart, cleanly dressed, and everybody was, you know, smart-dressed, and you did really smart things at the discos. And although that was making money, it had no status.

"And somehow, there's always been this time-lag, it seems to me, with black American music, whereby you do something and it's enjoyed, but has no status, and then white people take it up and the genre gets status. So that 10 years later, it's really groovy to dress up smart and do good disco tunes. But it wasn't then, you know? So, I'm not trying to impose my views on Chic—but just simply from my perspective, the existence of them and what they were doing, was politically very interesting."

It was a good song, too.

"That's right—I mean, apart from that. It was a very nice song. I had the feeling about this song, that they had written this chorus and then backed off the implications when they came to the verse. And did what everybody in rock 'n' roll does— which is play safe and pretend that the whole thing was about personal relationships."

Wyatt laughs uproariously.

I have to admit, I tell him, just those lines, "At last I am free/I can hardly see in front of me"...

"It's a great couplet. I mean, I think that's great poetry, just those two lines."

Wyatt's version of "Shipbuilding," written by Elvis Costello and Clive Langer and also included on Nothing Can Stop Us—was he pleased with it?

"Well, I mean, really, all I was doing there was exactly what Costello and Langer asked me to do, as well as possible. Strictly speaking on those things, they're sometimes called collaborations, but they're not. I was working for them, definitely, and I just saw my job as trying to sort of live up to what it is they expect me to do."

A hit, in fact, the single was Wyatt's closest brush with "rock stardom" in many years. He's not very fond of the scene.

"The rock establishment in England reminds me totally of the Royal Family and so on, in a way that not even Miles Davis does in jazz. Not even in terms of their attitude to themselves, but in terms of their role in the mass media, the newspapers and so on. And that may all be fine — there's nothing necessarily wrong with that kind of acceptance except that...I dunno, one thing and another, I didn't feel that I was part of something that really meant anything to me. So I was really looking elsewhere to act. But I couldn't find anything else, it was sort of too late. This is all I can do. And so I've come back to making records."

Wyatt's most recently recorded album, Old Rottenhat, came out last year in England, this year in the States. It's a remarkable record, filled with brand new Wyatt compositions, his first in many years. Political references abound: there are mentions of linguist Noam Chomsky, Indonesia, East Timor, songs like "The United States Of Amnesia" and "The Age Of Self." All of this, mind you, miles and miles away from the genuinely hilarious Soft Machine lyrics Wyatt penned almost 20 years ago—but certainly much more incisive.

Wyatt's earlier comment about Chic doing "what everybody in rock 'n' roll does" ("play safe and pretend that the whole thing was about personal relationships") is most telling.

Nowadays, Robert Wyatt says he is "more likely to go to a political meeting without any music in it, than a musical meeting without any politics in it." He claims to not be in touch with the London jazz scene as he once was because, "like Duke Ellington said, I don't get around much anymore." He recently went in the studio with British saxophonist Evan Parker for a short bit on Kip Hanrahan's next record, a collection of poems by Paul Haines. He's got no idea what he'll be recording next.

He's one of the most inspiring individuals I've ever encountered.

"I don't think I choose to make a certain kind of record," he told me about Old Rottenhat. "When I remember making records, I make the only kind I can. My ambitions are very simple.

"I try to make records that I would like to

listen to. It's as simple as that."

Dave DiMartino

|