| |

|

|

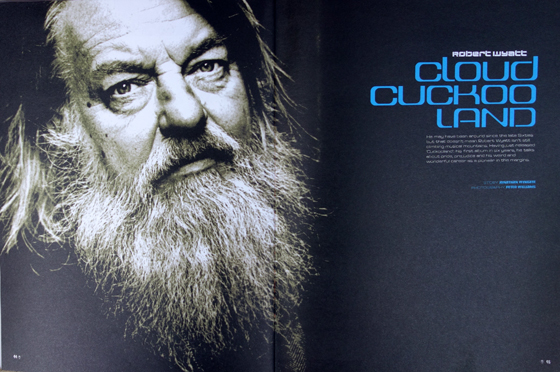

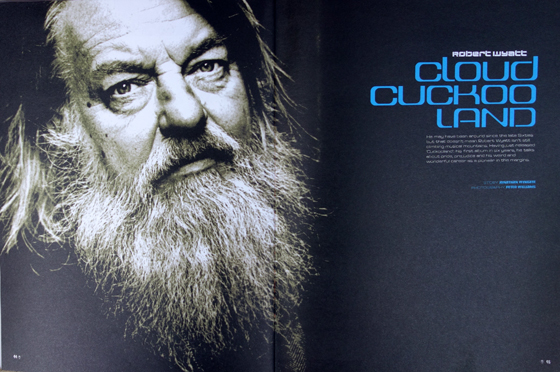

Robert Wyatt Cloud Cuckooland

- Straight No Chaser - Winter 2003 Robert Wyatt Cloud Cuckooland

- Straight No Chaser - Winter 2003

|

" I like being interviewed, but: I'm quite nervous beforehand,"

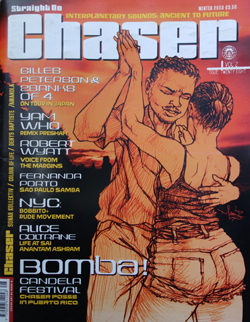

he says, maneuvering his wheelchair next to one of the gleaming chrome tables that line the balconies on the South Bank on a boiling hot August afternoon. He removes his black gloves and offers a firm handshake and a warm but ever so slightly wary smile. "Making music isn't an intellectual activity for me. It's an animal activity, like eating or sleeping. The moment you talk about it, it's inevitably pretentious. It's such a physical activity that anything you say about it has a vague whiff of bullshit about it."

We are here to talk about the release of 'Cuckooland', his first LP since 1997, yet by the time we say our goodbyes, our interview has lasted closer to three hours than the scheduled sixty minutes, and we have covered a plethora of subjects ranging from Coltrane to Communism, via Hendrix, humiliation...and archery.

'Cuckooland' is probably his most cohesive and accessible album so far, but it is still just as on the money and edgy as anything he's recorded since 1974's startling Rock Bottom. Ryuichi Sakamoto once said that Robert Wyatt has "the saddest voice in the world," although today Wyatt (incorrectly) describes how "my ever decreasing vocal range is now more or less reduced to a wino's mutter.

"Actually, I am incredibly happy with 'Cuckooland'," he says, when pressed, two hours into the interview. "I wanted to see if I could get the whole length of the CD and try and not be boring for a minute. I've never even attempted it before. It's like somebody who's only ever written short stories trying to write a novel. I feel like I've climbed a mountain, and I feel really at ease and light-headed now that we've got there.

"But nobody could call it a solo album. There are some great people on it like Gilad Atzmon, Annie Whitehead and Jennifer Maidman, who used to be Ian Maidman. She's much happier now as Jennifer than he ever was as Ian."

You could never accuse him of doing the hard sell. What Wyatt doesn't mention is that his guest list of pedigree chums also includes Paul Weller, David Gilmour and Brian Eno, whom Wyatt has worked with on numerous occasions since he sang on Eno's Taking Tiger Mountain. What does Brian Peter George St. John le Baptiste de la Salle Eno - the ultimate mystery man - actually bring to the making of an album?

"Well, it's very hard to say," he smirks. "I couldn't really define the contribution made by Brian Eno, who darts in and out of things in an entirely unpredictable way, leaving a trail of discreet magic in his wake. He played some synthesiser, he sang on Forest, and he put some extraordinary little guitar effects on the last song. He's just around, really. He gave Alfie a fantastic massage when her back was hurting, he brought a fantastic piece of fruit from abroad that we ate...and it made us all sort of better. He's just a magician...like a magic fairy."

|

|

Robert Wyatt's mother Honor, worked as a producer for BBC programmes like Woman's Hour, while his father, George Wyatt, was on industrial psychologist until he was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis. "My dad played piano, but I didn't meet him until I was six. Shortly after he joined us, he contracted MS, so he couldn't play piano or work by the time I remember him. So as a teenager, my parents were living off lodgers. My big brother, Mark had an alto saxophone, and he used to bring home jazz records, so there was always music in the house."

What music were you hearing when you were growing up? "The first things I heard were my dad's records - 20th Century classical music like Stravinsky, Bartok, Debussy and Stockhausen. My brother brought things home like Ellington and Mingus, although it still didn't occur to me that I could play jazz because it seemed so bloody difficult. I started to hear people like Ray Charles and Nina Simone, and I knew I wanted to do this. Then I looked in the mirror, and I thought: You don't look a lot like Ray Charles, son," he laughs. "That was the start of it, really.

"I've got the same record collection now as I had as a late teenager," he continues. "I used to like the records because they were new, and I now I like them because they're old. Mingus, late 50s Miles Davis, Coltrane...right back to Louis Armstrong. I never thought I could play this stuff. It was just music that I used to listen to. Jazz certainly seemed like another world. My dad loved the whole thing of bohemian Europe in the 30s. The avant-garde movements in the arts, surrealism, Dada and all those things were steaming away in my dad's mind, and therefore, in our house. I'm still working on what my parents gave me in terms of culture. I don't think it would have mattered if everybody had stopped making records in 1962. I'd still have plenty to listen to."

Robert Wyatt was born in Bristol in 1945. As the drummer and sometime singer with the legendary Soft Machine, the group he formed in Canterbury in 1968, he established a unique style that mixed melancholy music with his strange brew of English eccentricity and avant-garde jazz-rock.

"I spent all of '68 on tour with Hendrix," he recalls. "It was all just a bit of a blur. The Paradox is that it was because he'd done such disciplined homework on his music that he was able to be so free with it. If he went off on a solo, he could go anywhere and get back to base because he was so well drilled in the first place. He'd worked with The Isley Brothers and Little Richard - those bands were run like army units.

"It was soldiers coming, lock up your daughters stuff," he says. "Rock musicians tended to be like little princes with their retinue of servants. Hendrix was very courteous...an absolute gent. My eyes still actually water at the memory of him as a person, I can tell you. Compared with the boorish lumpiness that one associates with rock, Hendrix was a very feline person among a lot of very lupine characters."

After three groundbreaking LPs, Wyatt found himself having less and less say in the creative direction Soft Machine were taking, and by the time they came to record their next two albums, he had already made his first solo effort, 1970's patchy End Of An Ear. "I recorded End Of An Ear while I was with Soft Machine in exasperation. I just wanted to open the Windows and shout my head off a bit, which is what I did. But it was useful preparation."

Wyatt was soon fired from the Softs without warning for reasons he still doesn't understand over 30 years later. "I don't know why they kicked me out," he says sadly. "You'd have to ask them. I just got a phone call saying 'we've got another drummer'. I respected them so much that I thought they must be right and I deserved it. I thought Soft Machine was my family. I've thought of a million reasons why they asked me to leave - all perfectly justified - and that didn't leave me feeling any better.

"I think what really hurts is humiliation," he continues, staring out blankly over the Thames. "When people try and analyse the unrest in the world, they always think in terms of the haves and have-nots, but I think humiliation plays a big part in unrest, politically. Oscar Wilde was right - nothing is worse than physical pain, but in terms of debilitating battles of the mind, anyone who's been rejected will know that it's such a bombshell that it's unbelievable how it can wreck you."

Wyatt now looks upon the 60s as "a bit of a waste of a decade, at least as far as me getting anywhere was concerned. I think I'm probably a late developer. It wasn't until the 70s that I started really working on how to write tunes and put things together. I'm nearly 60 now, and from my point of view, I preferred all the other decades I've lived in. A lot of things came to the surface via popular culture in the 60s, but they were mostly things that had already been steaming away in various underground circles, whether it was Rhythm & Blues or the whole psychedelic scene. It was all put through the rock 'n' roll sausage machine and made accessible. But I was quite happy when it was just underground myself," he laughs. "I like this secret Society thing. When these secret society's persisted, like the Mod thing and the Northern Soul thing, I really admired that, because you didn't have to read the fashion magazines to find out about it.

"I thought The Beatles were alright," he says, "but not transcendental. The Beatles was cosy, whereas people like Coltrane take you to Planet Z and then drop you back gently on earth. If I'd got into The Beatles before jazz, maybe it would have moved me more."

He soon got another group together called Matching Mole, who made two albums before disbanding. "It was such a chaotic time. I suppose I started to drink for the same reason as anybody else does - because I've got a low boredom threshold. We were all drunk, and the only thing I salvaged out of it was that somewhere in there I married Alfie and had two kids."

In the summer of 1973, Robert Wyatt got drunk at a party, fell out of a fourth floor window and broke his back, leaving him confined to a wheelchair for the rest of his life.

"I was barely conscious when I fell, and I wasn't conscious at all when I landed," he says. "It's like it happened to somebody else. I remember lying there for a second and hearing this amazing scream echoing across the courtyard that I'd fallen into. Later, somebody told me that that was me."

Did the accident change your attitude to life? "No," he replies, stubbing out a cigarette. "It was like falling off a bicycle. I just fell off and got back on from another angle. It was a bizarre diversion...a bit like a long dream. When you wake up, you're disorientated and you can't quite remember the story. I was unconscious for six weeks, although I was in hospital for nearly a year. When I came out of hospital, I got stuck straight into the music. I'd actually written a lot of 'Rock Bottom' just before the accident.

"I found an unused room in the hospital with an upright piano in it. The alternative to hiding in that room was being taken off to do archery or wholesome exercises. The archery teacher was a funny bloke," he continues with a grin. "He'd come up to you and say: 'I used to work for the LA Police, you know. I don't have to be doing this.' I'd say: 'Right. OK.' So, archery didn't really take off with me."

'Rock Bottom' was followed a year later by 'Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard', another astonishing box of tricks that included the first of Wyatt's two hits, a cover of The Monkees' I'm A Believer' as well as the song, 'Sonia', composed by South African trumpeter, Mongezi Feza, who died from double pneumonia in an English hospital. Wyatt believes that if Feza had been born white, he would have survived. He also believes it was this incident that acted as the catalyst to kick-start his lifelong fascination with politics. He spent many years as a member of the Communist Party, although he is not a member of any political organisation these days.

"When he died, I was so angry that I think that was a sudden jolt into much more immediate politicization," he recalls. "I suddenly realised that politics wasn't such an abstract thing...it wasn't just conceptual or a theoretical thing. Why is it that he'd come all the way here and bring us such fun with his music and then die like a dog in an institution? I just thought: Fuck this, you know? So I really started to find out what apartheid was all about, because I was such a fan of black music. I just couldn't square the circle of these wonderful people and their music and how life seemed to be so unfair.

'Then I started reading up about it, and the only people who ever really explained things in a way that made sense tended to be anarchists and Marxists. I started to get interested in how the world was run and who ran it on whose behalf. Mongezi's death definitely kick-started politics into the frontline of my consciousness. I got more and more involved in politics, and in looking for musical connections in politics."

How would you define Communism? "I have a very simple motto - an old trade union motto: Nothing is too good for the workers. If there's one spare penny going out of any enterprise, then it seems to me that the people who should get that spare penny are the people who did the work, not the people who own it."

Wyatt became increasingly involved in politics and enjoying a normal life. "I got involved in Communist Party activities, but I was also enjoying having a life with Alfie. I wanted to have a life and just get by, you know? But you can't. You've got to earn a living. Me on about the workers - there was no point in just watching them."

He was introduced to Rough Trader Geoff Travis, who persuaded him to get back into the studio and start making music again after a five-year hiatus. "I released a few albums with Rough Trade. I try and make records that I don't think anybody else is gonna make. There's no point in thinking: I'd really like to be able to play alto saxophone like Ornette Coleman.

"I shift through all the various noises in my head until I hear something that I can't imagine anybody else making," he explains. "When I actually write, I pick up a certain harmonic idea and it will float about like a virus for years in my brain. It's a very slow process. I wrote a lot of 'Cuckooland' within a year, but I was also using bits and pieces I'd had knocking about for 10 years. Some of the songs are older than the stuff on 'Shleep' - they just hadn't found a home. I find it quite hard to come up with more than about one song a year, so I sometimes find other peoples' tunes to do to complete my CDs."

His other chart entry is his breathtakingly beautiful take on 'Shipbuilding', Elvis Costello's anti-Falklands War lament from 1983. "I didn't really understand the song," he says. "They're amazing lyrics. I was very honoured that someone as on the ball as Elvis Costello had written to me and asked me to do it."

Wyatt's career has brought him precious little commercial success, although today he is undoubtedly one of the most influential avant-garde artists of all time, and albums such as 'Rock Bottom', 'Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard', 'Old Rottenhat', 'Dondestan' and 'Shleep' are considered to be timeless classics by those lucky few in the know.

"I have no idea what influence I've had, because, like I said, my record collection stopped around 1962," he grins. "I mean, you talk about the effects of paraplegia... I suppose I can't easily get around in a practical way, but it seems to me that I have probably compensated for that by becoming fantastically emotionally and mentally connected with lots of the rest of the world through my music."

How did you feel when you were asked to curate the Meltdown Festival a couple of years back? "I looked at my record collection and thought: There's nobody in it who's still alive," he chuckles. "Then the bloke who organises it sort of nudged me into realising that there was life beyond Miles Davis."

Wyatt hasn't stepped foot on a public stage for over 20 years now, and says that he will never do so again at any price. "I can't cope with a room full of people staring at me," he says. "I get so nervous. I tried doing it a couple of times, and I'd drink, and then I'd forget the words. I last sang on stage in 1983 with The Raincoats. For a lot of people, their main source of income is from touring. It would make me absolutely sick with fear. You know when you turn the water on with those rusty taps, for the first five minutes it's just brown water until it's cleared? Well, my music is a bit like that."

Robert and Alfreda Benge aka Alfie, who has contributed poetry and cover art for many of Wyatt's albums ever since they got married almost 30 years ago, tend to spend most of their time at home in a big old house in Louth, Lincolnshire. Wyatt sits at his piano downstairs and plays his records constantly, while Alfie is often to be found sitting upstairs painting her pictures: "I do karaoke at home...I put on records and join in. I listen to music incessantly...day in, day out. Alfie's art room is upstairs, and I can't go up there because of the wheelchair. She could stand at the top of the stairs and throw buns at me and say: "Fuck off," Robert Wyatt laughs. "But she doesn't. She's too polite."

Robert Wyatt's 'Cuckooland' is out on Rycodisc

|