| |

|

|

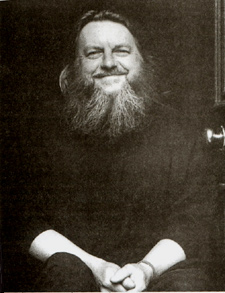

Robert

Wyatt & Alfreda Benge - Dream Magazine #5 - Spring 2005 Robert

Wyatt & Alfreda Benge - Dream Magazine #5 - Spring 2005

ROBERT WYATT & ALFREDA BENGE

|

|

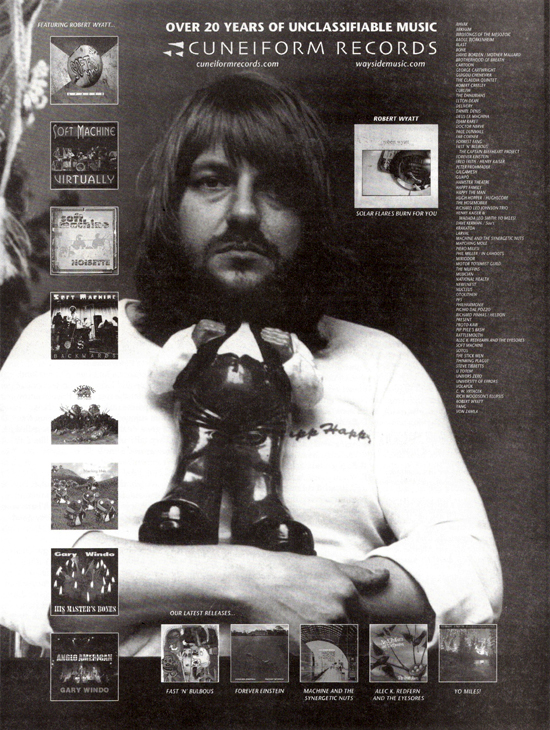

It was a rare treat to speak to

Robert Wyatt by phone for this interview, I'd like to gratefully

acknowledge Joyce at Cuneiform Records for kindly setting

this up. When I first dreamt of doing Dream Magazine, Robert

Wyatt's name was near the top of the list of folks I wanted

to talk to. I've been tuned into his stuff since the first

Soft Machine album, though he had recorded as early as 1962

as a member of The Wilde Flowers, and as a solo artist,

continues to this day as one of the most artistically vital

avant pop composer/singers of his, or any generation since.

His angelic lighter than air voice is one of the most unique

and lovely ever recorded, his continuing creative flow reveals

some of the finest work in a forty-plus year career. His

open armed embrace of jazz, folk, pop, socialist politics,

intelligence, wit, minimalism, progressive rock, compassion,

psychedelia, several different international musical forms,

and his own distinctive vision is a singular contribution

to the history of recorded music. He's worked with folks

that range from Jimi Hendrix, Syd Barrett, and Brian Eno,

to newer artists like Björk, and Hood. It was also

great to get to talk to Alfreda Benge, who is: illustrator,

instigator, inspiration, coconspirator, often lyricist,

and painter wife of Robert Wyatt, (also the subject of many

of his songs). Robert and Alfreda deserve a book, not just

this truncated chat; though we talked for over an hour,

I felt like we were only scratching the surface.

G.P.: Hello Robert.

R.W.: Can you hear me OK?

G.P.: Yeah.

R.W.: This is a different phone. Maybe it's because

a blizzard is coming, or maybe it's just weather stuff going

on.

G.P.: Could be. I'm hoping we can also talk to

your wife and frequent collaborator Alfreda later on, if

that's possible.

R.W.: A good idea. She's upstairs right now, but

will be down later. I'll ask her if she's up for it when

she comes down.

G.P.: You've worked repeatedly with certain folks;

you worked with Michael Mantler, and Carla Bley, and now

their daughter Karen.

R.W.: Right. (laughter)

G.P.: She contributed quite a bit to Cuckooland.

What is it about those folks that you found such an affinity

with?

R.W.: Well they're a great family. I think each of

them is really unique; you can't really describe the genre

of music they're into. It's really fascinating; the parents

are very disciplined for jazz players, and it's interesting

to see Karen coming out of that background. Although I'm

of the same musical generation as her parents; the fact

that Karen makes her music out of recognizable notes, and

songs and like that; makes her music much more like mine,

than her parent's is. But, she brings that kind of careful

and astute knowledge of music to it.

G.P.: Her pieces work really well on Cuckooland.

R.W.: Well I'm glad you think so. The other thing

is she's so... I mean Karen went through a punk period,

kind of as a teenager. But the fact is she's learned a lot

of discipline compared to me; and I was sort of interested

in playing the role of kind of wicked uncle; and kind of

messing it all up a bit. (laughter) Getting some of that

dirty noise in there.

G.P.: It also feels like you're sort of a member

of the extended Pink Floyd family.

R.W.: Well, I don't know. It's actually rather distant,

the thing about Pink Floyd is that it's actually another

planet really; the planet "rich" for a start.

Not the undeserving rich, they're rich because other people

buy their records.

G.P.: You have worked with most of those people

though. Can you tell me a bit of what Syd Barrett was like

as a person?

R.W.: Well, he was very nice.

G.P.: Not a loon huh?

R.W.: In those days how could you possibly tell?

(laughter) I mean what would have been unusual about that?

G.P.: (laughter) That's true. What did you work

on together?

R.W.: I played drums on a few tracks of A Madcap

Laughs.

G.P.: I really enjoyed the album Songs

by John Greaves, it featured you on three tracks. How did

that collaboration come about?

R.W.: I've known John a long time, and Peter Blegvad

is one of the great wordsmiths of our time.

G.P.: Oh yeah.

R.W.: Anyway they just asked me if I would sing a

few things. [Lengthy response that is inaudible].

G.P.: Who or what are some of your conscious songwriting

influences?

R.W.: You know I have no idea, I can tell you what

I enjoy. American writer Ogden Nash for one, the best songwriter

that I can think of is Randy Newman.

G.P.: Ah, he's incredible.

R.W.: There are a lot of people that kind of get

to me and John Lennon was one of them, but for the rest

I don't really know. I can't separate influences from things

that I've enjoyed. I forget to mention this but a great

deal of what used to be called , the "hep talk"

of the 40s and 50s, like Cab Calloway and Slim & Slam,

maybe you don't remember that.

G.P.: Sure I do.

R.W.: Alright then, you'll know what I'm talking

about. Like the mad lyrics that Dizzy Gillespie used to

do like "sh'bam, a gloog a mop" which I think

is a very good line.

G.P.: (laughter)

R.W.: (laughing) I think that's as good as anything

Little Richard came up with.

G.P.: I really enjoyed your contributions to the

Winged Migration film; how did your participation

happen on that project?

R.W.: They pretty much just asked. Composer Bruno

Coulais does music direction for that filmmaker's (Jacques

Perrin) various subjects. This time they wanted to do the

thing you're not meant to do; which is to anthropomorphize

the subjects. So in other words it's not a straight nature

film. The original title in French is "Migrating

People".

G.P.: Oh really?

R.W.: And I think that's a good title really. And

uh, so anyway they wanted some singing on it and they asked.

And I said "I don't normally do things like this."

They said: "It would really only be your voice and

our lyrics". And when I heard it they had me.

G.P.: Well, they really sound like pieces that

you might have written.

R.W.: Yeah, well that's what he was trying to do.

It was part of his way of getting me to do it.

G.P.: What did you think of the finished film?

R.W.: Oh, it was very nice. The words were originally

written in French, and had to be translated into English

in a singable way; so Alfie; as is often the case; uncredited,

but she's really shy about getting credit. But on the other

hand she does all this stuff. She actually rewrote the whole

thing to make it singable for me. I couldn't have done it.

In fact when I first got the lyrics, I said "I can't

sing this." But she reworked is so that could. So she's

the hidden ingredient there; the catalyst that made that

work.

G.P.: You have long been a supporter of animal

rights, what would you say to someone to raise their awareness

regarding animals and their treatment?

R.W.: Well, not to proselytize; but as far as I'm

concerned we're all animals. And anything that's got a beating

heart, it's just trying to live like you are. So if you're

going to eat it or use it, go ahead. But just sort of think

about that for a moment. Try to be nice to it while it's

alive at least.

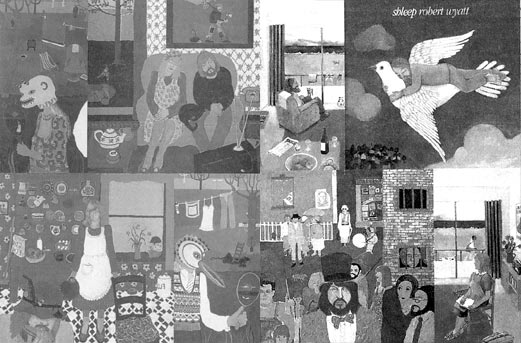

G.P.: Tell me about your album Cuckooland

and how it came into being?

R.W.: Well more than anything, as you may know about

the last couple albums; were sort of kick-started by taking

some of Alfie's lyrics and putting them to music, or occasionally;

as is the case with Alien, from my previous album

Shleep, where she actually wrote words to my music.

But in this case I don't think the record would have interested

me without Alfie's words. I just haven't got enough coherent

material, I had sort of scraps of tunes knocking about for

years literally. And Alfie said we had to just get on with

it, and do it. It's how we earn our living for a start;

I get a pension, but this a large part of our income.

G.P.: Well it's interesting how it feels so coherent;

it doesn't seem put together it feels like a piece.

R.W.: Well I think that's why it takes me so long

to get things together. Everything has to be sort of re-tailored

and remade so that it feels natural and organic. But I think

in this case; the musical ideas I had, reduced the lyrics

to sort of mantras and things, and I really was getting

nowhere. And Alfie just went through stuff of mine. I dug

out some tapes; pre-digital stuff that I'd done. And she

wrote words to things, and came up with words for Old

Europe, and Forest, and Lullaby for Hamza.

And then she had some poems that she was working on that

became songs. Alfie's here at the moment; she's been upstairs,

she's been working on all kinds of stuff, but just came

down for a bowl of soup. So if you did want to speak to

her, this would be a good moment.

G.P.: Yeah, I would like to.

R.W.: OK, I'll hand you over to Alfie.

A.B.: Hello.

G.P.: Hello, well I kind of wanted to talk to

you about your part of the musical thing and your paintings

too. Who were some of your influences as a painter, or do

you have them?

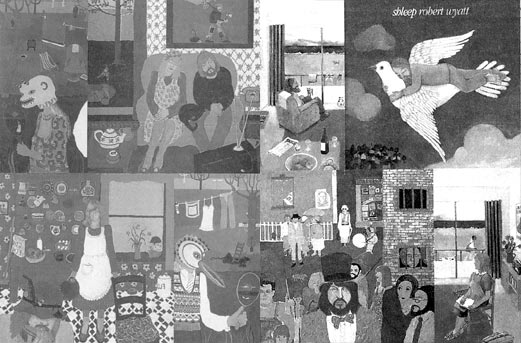

A.B.: Well I wouldn't call most of what I do for

Robert paintings really; they're sort of illustrations.

Ever since I've done paintings and drawings, I draw from

life and I paint out of my head. So all these images are

out of my head really. They're kind of narrative, most often,

sometimes they're more graphic, because I was into graphic

design. So I sort of apply various bits of my training,

according to what I think or feel the subject is. So, in

that sense they're illustrations.

G.P.: There seems to be a sort of surrealist sensibility

to some of them.

A.B.: Well, I don't know. They're not surrealist;

they're more jokey. They're almost paintings of cartoons

really.

G.P.: Uh huh.

A.B.: My favorite painters don't paint like me at

all.

G.P.: Well, who are they?

A.B.: (laughing) Well, I like Bonnard. I like the

use of paint by Matisse and Bonnard; all the old, boring

old masters of the 2Oth century really. I like Kurt Schwitters.

I like painters that use paint to paint what they see. I

like painters that use space nicely.

G.P.: Lately I've been obsessed with Charles Burchfield.

A.B.: I don't know him.

G.P.: Oh, try to find something by him. He did

some wonderful watercolors, he's unlike anybody else.

A.B.: Alright.

G.P.: When you work on lyrics for Robert; is it

a poem set to music, or do you hear the music first?

A.B.: Well they vary. On Dondestan they all

already existed and Robert just set them to music. They

were from a sort of diary, and he thought they had music

in them. And the same with the stuff on Shleep; except

for Alien which is the first one actually where he

got stuck for lyrics. For Alien he actually gave

me the music, and I sat about and listened to it for a few

days. I shut my eyes and tried to think what the story of

the music was. So bits of words would come in with the music.

With the music I think where am I in this picture, and sometimes

a series of notes will suggest a word, like Lullaby for

Hamza; I just heard 'lullaby'.

G.P.: Have you ever thought about doing an album

of your own ?

A.B.: (laughter) Well, I'd love to do that, yeah.

I'm a musical ninny; I could get the odd tune, the lyrical

tune, but I think, no. I have actually just been asked by

a French producer to write some lyrics for him, so I'm branching

out. I'm becoming the Grandma Moses of lyrics.

G.P.: (laughter)

A.B.: (laughter) I find it extreme fun, I've never

found anything more enjoyable actually. Because it's not

like dealing with a piece of blank paper. With a painting

you've got this big white space and have to put something

on it. But to be given a piece of music and to try to find

the words in that is real fun!

G.P.: It's like somebody's done half of the work

for you sort of.

A.B.: Yeah, yeah. They've done all the work really,

so the rest is just absolute fun. It's like if you do a

painting and get half the way through, and you know you've

got it, from then on it's plain sailing; it's that kind

of fun.

G.P.: Yeah, but you've gotta go in there and find

that thing.

A.B.: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, that's horrible.

G.P.: Yeah it is; that's scary.

A.B.: Also with poetics it's that blank page, but

it has some music to it too, and they all suggest visual

things to me anyway. They suggest places. I mean like Forest;

there was a forest, a river, some trees. Which is not to

say that it's always easy; because when you get down to

the details; the vowels that go to the right notes, and

Robert's ability to sing them. So it's not always easy,

but it's always fun.

G.P.: Have you had any shows of your paintings?

A.B.: Yeah, well when I was actually doing painting.

I don't really paint anymore; I mean I do stuff for Robert,

I do stuff when there's something to do it for. Yeah, I

had a show about 20 years ago. But I've never actually joined

the art world in that sense. A bit like Robert never actually

having joined the music industry. (laughter)

G.P.: (laughter)

A.B.: We just do what we do.

G.P.: Yeah.

A.B.: But in fact it's lovely to do it for records

because so many more people will see it than would if it

were at a gallery.

G.P.: Yeah it's a great portable gallery.

A.B.: Yeah, yeah. The same with poetry as well; with

Dondestan and Shleep it actually reached around

60 or 70 thousand people, and you don't get poetry selling

like that do you?

G.P.: No.

A.B.: So it's nice when it happens, but it's not

too connected to the real world.

G.P.: (laughter) Not directly anyway.

A.B.: No, not directly. Only as being a kind of leech

on Robert.

G.P.: (laughing) Oh God!

A.B.: (laughter)

G.P.: How parallel are your political views?

A.B.: Oh absolutely; except, I was born an anarchist,

so I would tend not to join things. Robert's more of a conformist;

he like the idea of belonging to something. But in terms

of worldview, and how things happen, and why they happen;

I mean we both it read between the lines in exactly the

same way.

G.P.: Right.

A.B.: We both scream in horror at exactly the same

lies, and I think we're pretty similar.

G.P.: How do you feel about the current US presidency,

and their foreign policies?

A.B.: (silence)

G.P.: You don't have to answer this.

A.B.: Yeah, no I'm just thinking what to say

really. Shocking, appalling, extraordinary, just horrible.

G.P.: Yeah, me too.

A.B.: Yeah, but you know in a way really I'm

more shocked by ours.

G.P.: Oh really? The Tony Blair complicity?

A.B.: Yeah, well because he's supposed to be

on the our side. I'm not surprised when people on the right

behave according to their beliefs, I can understand them.

But he was supposed to make things better for us. He's been

shocking here as far as being sort of power crazy, and proud

of the fact of being Bushy's best friend.

G.P.: Oh yeah.

A.B.: It's just so horrible.

G.P.: Yeah, it's nightmarish.

A.B.: Well do you want me to give you back to

Robert?

G.P.: Yeah I guess. It's been great to get

to talk to you.

A.B.: Okay, bye.

R.W.: That was a good idea.

G.P.: For a sense of perspective. You

said something about her sort of being the dark side of

the moon to your work.

R.W.: Yeah exactly, which is funny in a way because

she gets embarrassed as far as anyone drawing attention

to themselves, including me. If I get noticed at any kind

of social event she just dies on the spot of embarrassment.

But this is how I earn a living, somebody's got to get up

there and show their face occasionally, that's how it is.

G.P.: Well some people are not extroverted

in that way.

R.W.: Well I'm not very either. I mean the bit

about music I like is the solitary activity of making it.

Anyway; it's just that she is very shy. She speaks so well

you know, because she didn't start learning English until

she was seven. (laughing)

G.P.: Oh yeah, where's she from?

R.W.: Poland, her mother's Polish, well she's

a mixture of all kinds of things really. She's from the

land, and the forest, and about. I think that's why the

Forest song came up really. She has ancestral; or

at least childhood memories all mingled up with the forest,

but also the whole world being a sort of a bombsight; as

it was when she was a child.

G.P.: That's a great song!

R.W.: Yeah, well it's pretty heartfelt I think. The

stuff about Alfie that comes out, probably paradoxically

enough, the truth is true of what she does.

G.P.: And it's always nice to hear Brian Eno singing.

R.W.: Isn't it eh?

G.P.: I wish he'd do that more!

R.W.: Oh I know, l know! I tell you he's been working

on some stuff, and we've been seeing quite a lot of it during

the last year; and his studio is quite near Phil Manzanera's.

He's been making such interesting stuff; but he has the

same problem I have, of finishing things. But he's the very

opposite to me, in the sense that he's very very high tech,

and digital. I mean he's got hundreds of things carefully

filed and stored, and making more every day. And he buys

every new Japanese toy there is.

G.P.: (laughing)

R.W.: He's here one day, there the next. It's on

and on; he's out there. It's Barcelona on thursday. He gets

around and sees things, and he's always so on top of that

kind of stuff. But maybe that's part of his thing, but he

we're all able to talk about Brian Eno's thinking; his ideas

and so on. I mean just as a pop musician; I think he's terrific,

you know. Songwriter, singer...

G.P.: Oh yeah! And he's got such a lovely distinctive

voice.

R.W.: He has, he has, and funnily enough for all

his high tech, he's very old fashioned about it. He stands

there full sway like an opera singer, and delivers, and

it's really strong. (laughs) He's terrific, a terrific singer.

The stuff he did was sort of backing vocals and you will

have gathered, we sort of managed to take away the top layer,

to reveal what he was doing underneath it, you know. And

then David Gilmore, he provides the magic fairy dust on

Forest for me.

|

G.P.: Yeah, it's a beautiful piece of work.

R.W.: Because he obviously contributes his guitar

solo, but also his pedal guitar all the way though it is

just terrific you know. He did a lot of work on it, you

know. And I hadn't asked him. We met a few times again after

20, 30 years or so, and he and I get along well, and I like

his band members. But I get along better with the blokes

than the gang. You know groups have a thing that way. Four

young men in a box, you know.

G.P.: Did we cover the making of Cuckooland;

what inspired it?

R.W.: I knew we had enough stuff; the key to it came

when Alfie came up with the words to Lullaby for Hamza.

And the rest is just getting into gear and getting on with

it. And Phil Manzanera who produced the opportunity to work;

the way he did it was; he just had a budget for the making

of the record, and he just said; "However long it takes."

And it won't bring the price up, which is an amazing thing.

G.P.: That's sensational!

R.W.: Well it was incredible. I mean he's always

had money troubles; but he's just like that. He said "I

don't do something by a written company's name, because

I don't want to put up with that." In the past so much

he'd been part of ended up owned by some alien reptilian...

G.P.: Corporations.

R.W.: That's right. Luckily some people from that

era, have rescued that era. Lovely folks like Steve Feigenbaum

of Hannibal Records, or the folks at Hux Records in England;

but on a whole it's as easy to get buggered about by people

of that era. There are some nice people to work with; the

Ryko lot leading the way in America. They're conscientious,

and hard working. These things aren't terribly romantic,

but they are absolutely vital. Because apart from everything

else this is a job, this is what we do for a living. It's

really hard; it does take a bit of time and attention. It

just doesn't get the kind of massive sales that like commercial

releases get, so they can't really be indulgent in the way

that musicians might tend to want them to be. As for myself,

I haven't paid anybody like Brian, David, or Paul Weller;

because I couldn't afford them. But I pay the regular professional

musicians; like Annie Whitehead.

G.P.: You've chosen some interesting songs to

cover over the years: the Neil Diamond/Monkees song I'm

a Believer, Chic's At Last I am Free, and recently

the Bordeleaux/Felice Bryant song Raining in My Heart;

what is the criterion for choosing covers for you?

R.W.: Well really I always want to remind myself

and anybody who's interested, that I do have a great love

and respect for pop music and what it can be beyond just

being music for teenagers. And I wish to disassociate myself

from those elements of the avant garde, and experimental

music scene that have openly expressed their distaste for

pop music.

G.P.: Well that snobbery seems kind of foolish

to me.

R.W.: Well it's particularly distasteful coming from

a culture that's meant to be a kind of alternative to an

antique established establishment. You don't want to see

a kind of conservative, elitist, snobbishness reemerging

in the avant garde. It just doesn't belong there

G.P.: You sang with Brian Wilson on a Ryuichi

Sakamoto cover of the Rolling Stones 'We Love You',

did you actually meet during that recording?

R.W.: No, no I didn't know he was on it. Ryuichi

just wanted me to sing it; and yes the reason that I did

it was because Ryuichi asked me to. The Japanese have such

a nice way of asking; I thought, this is such a nice letter,

I really ought to do this for him.

G.P.: It's really a nice version of that song.

R.W.: Well it is; but the idea that I would ever

sing a lyric by that songwriter. I don't know; I wouldn't,

myself have chosen that song. But that said; I don't really

feel at home in rock culture. But it wasn't because of the

song; it was because of Ryuichi has such an amazing, sensitive

expressive musical ear. He has a fantastic musical knowledge.

G.P.: Ah, he's a wonderful musician.

R.W.: Well he's actually a great musician in the

sense of a being a classically trained musician. That kind

of refinement of technique; he has it. I didn't know Brian

Wilson was on it till I heard it. And you can't fault that.

G.P.: (I turn over the tape. As I do I tell Robert

that I hope it's all recording; part of his reply gets recorded)

R.W.: Well then you might have to do it back from

memory. Like a dream, which seems fitting. (laughter)

G.P.: Well I can try! (laughter) Do you think

it's surprising that you might be doing some of your best

work at your age?

R.W.: Well I'm very relieved to hear you say that

because one of the things I felt uncomfortable about was

the relentless emphasis... It's a bit like the aesthetic

today is that it's only a youth thing. You know it's a wonderful

stage to go through; but it's really amazing if you have

any luck, how much of your life, isn't youth. It's decades

and decades of watching and learning, and finding things

out. And you're quite lucky if you survive long enough to

really have time to have thought about things, and worked

through your ideas. So really it should be the case that,

that when you come up in age, you should benefit from that.

G.P.: Well I think part of the problem is working

from the template of a pop artist is erroneous; when looking

at artists in other fields their later years are often their

most fruitful.

R.W.: Well that's sort of acknowledged in many arts,

but for some reason it's kind of doesn't sit comfortably

with the way pop music is promoted; which is fine. I think

the kind of central thing of rock, and of pop music is it's

a celebration of youth. It's wonderful and I think every

generation should happily have it's own sort of coded language,

and it's own haircuts, and it's own group sounds, and it's

nobody else's business. On the whole pop culture is a wonderful

thing and it is about youth. And the fact is that it comes from a much wider and older tradition,

which is sort of folk music really. And if you look for

the origins of rock & roll and pop, it's sort of

Irish and American country music, and then the Black equivalent,

and the Italian equivalent, and so on, and so on. And that's

the roots of it; and that's a much bigger river. A bigger

broader river.

G.P.: And connected to a lot of other rivers.

R.W.: Yeah. And there's a lot of music that isn't

pop music at all. Still I think the life's blood is singable

songs and dancible rhythms. I think Charles Mingus said

that.

G.P.: So are you a jazz artist or a pop artist?

R.W.: I can't place myself in music at all really. The kind

of people that I relate to, if anybody; I'm not comparing

myself with the quality of the work of these people, just

that I identify with as people who are working their way

through their lives; over decades and years. The painters

that I like; from the early part of the 20th century. Some

of the ones that Alfie mentioned; and Van Gogh or "Van

Go" as they probably say in America.

G.P.: No we can pronounce it right here sometimes.

R.W.: (laughing) Well it's (correct pronunciation)

in Dutch.

G.P.: Yeah it's got that (throat sound) it's hard

to do.

R.W.: It's like Flemish; it's unsayable.

G.P.: You know Jonathan Richman wrote that song

about Vincent Van Gogh; you may not have heard it.

R.W.: I like Jonathan Richman.

G.P.: He said he was really lucky that he didn't

know how to pronounce it when he wrote it. Because Van "Go"

rhymes with a lot more stuff

R.W.: (laughing) Yeah, right. Very good. Anyway,

you know who I'm talking about. And Marc Chagall, who's

original name was Moishe Shagal.

G.P.: Oh yeah? He's wonderful, very magical.

R.W.: Great great, and part of the wonderful part

of the great Russian Jewish tradition that has given us

stuff in every field. I can't imagine what the world of

music, or ideas, or science, would be without their contribution.

And yeah, I don't know; sorta Joan Miro. Yeah I was very

interested in Joan Miro of Catalan, and how those people,

grew old interested me. Late Picasso, late Miro; where all

of the apparent elements of craft are just gradually discarded,

and we just get this sort of like hieroglyphic, childlike

scrawl that they would have started out with. And I find

that quite a moving process. So those are the sort of people

I feel on the same planet as; let's put it like that.

G.P.: Could you tell me a bit about the BBC documentary,

Free Will And Testament?

R.W.: Well that was suggested to me by a man called

Jez Nelson, who does a jazz program on radio BBC 3, and

had the opportunity through the participation of BBC 4.

And I was surprised that he'd ask me, because his main work

is in new jazz; but he does other stuff as well. Anyway

he asked Mark Kidel, who is a very good filmmaker, a very

good director who works in England. And he'd approached

us a few years ago anyway about making a film, but hadn't

gotten anyone to back it; so then Jez Nelson gave him that.

So they went to me; well "What do you do?" Well

I got so embarrassed that I don't do anything that I said

well; "I could sing some of the songs that Annie Whitehead's

band does, and I can sing them with Annie." And it

ended up getting done on film.

G.P.: Well I hope that it gets shown over here.

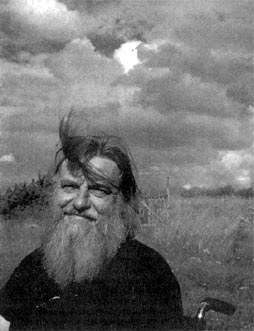

R.W.: Well Mark, I think he put it together very

well. I think it's difficult work to do, because I just

sort of sit here like a cactus in the desert really.

G.P.: (laughter)

R.W.: Like some kind of Andy Warhol film really,

like the Empire State Building. (laughing) But he made it;

he sort of condensed things so that it seemed like lots

had happened. I remember they were making a TV film about

Quentin Crisp here in England; and John Hurt was playing

him. He was talking to Crisp and said "I hope we can

get an accurate picture of your life." And Quentin

replied "Oh I hope your film is far more exciting than

that." (laughter)

G:P.: (laughing) That's great!

R.W.: (laughing) Yeah, I hadn't realized till I saw

Mark's film how uninteresting I am.

G.P.: What are some of your thoughts regarding

, the current US president and his foreign policies?

R.W.: I don't know, you see. There are so many great

Americans that I get very upset when people say that people

like me are being anti-American. I say "No I'm not

anti-Michael Moore, I'm not anti-Noam Chomsky." I probably

more immersed in great American culture, than most of those

people who claim to be representing it. You know what I

mean? I could talk to any of those people in his cabinet

about Mingus and Charles Ives, and they couldn't catch me

out on a detail. So don't talk to me about being anti-American.

I can't imagine my life without the American cultural influence;

which I attribute to the fact that it's a country of mass

immigration from all around the world reconfigured. That's

the magic of America to me; and a great gift to the world.

I mean looking at American history which is rooted in part

in English history, which is why the language that were

speaking is called English. And people think that it's something

fake, or sort of wishful thinking that the point of America

is that it's the land of the free. ln fact the freedom that

the British settlers, as I understand it; were looking for.

Was the freedom to form these very tight strict religious

sects, away from the kind of liberalizing influences that

were spreading through Europe. So although it was a freedom;

there was embedded in it a freedom to be more conservative

than their European ancestors. Rather like the Afrikaners

who left Holland precisely it was becoming free and easy.

They wanted to stay strict to the Calvinist type rigidity;

you know tribal rigidity. So it's always been kind of ambiguous

in that sense. My message to America is "Look we love

you already, so leave us alone!" (laughing) You know

what I mean, you don't have to keep knocking at the door

saying "Love me more, love me more." You know

I think it's an embarrassment for the Americans I know;

what's going on right now. Who just sort of sit back and

watch this stuff. Well you know, Noam Chomsky was asked

"What would you put in its place?", and he said

"It's very simple; to start out. Stop doing bad things."

(laughter) "Start there."

G.P.: (laughing)

|

|

|

R.W.: That's a pretty good one isn't it?

G.P.: It pares it down to something pretty simple

and understandable.

R.W.: I think he's great, I love Chomsky.

G.P.: Oh he's great; and it's nice to hear you

mention Michael Moore; he's actually got relatives here

and has visited a few times.

R.W.: Oh really? Well we were lucky enough to see

Michael Moore in action on stage in London where he got

a full house every night. As great as the films and the

books are; the stage performance was uh... I felt "I'd

witnessed someone in the great tradition of Lenny Bruce

and Mort Sahl; you know what I mean?

G.P.: Yeah, he's brilliant.

R.W.: That's the dark side of the moon that we hope

gets spun 'round to the front one day.

G.P.: How inspirational was your early meeting

with Daevid Allen?

R.W.: Well the main thing about Daevid was he was

older, and hadn't been through the stuff; that me as a schoolboy

had been told that I was gonna have to do. You know, passing

exams and all that. Well I was rubbish at passing exams,

I was rubbish at school. (laughs) Daevid showed me that

you are allowed to fail exams really. He was already in

his twenties when we were schoolboys.

G.P.: A sage old fellow.

R.W.: And he was already out there doing stuff. He

already had contacts in Paris and London with some people

in the avant garde scene. So that was the influence there

really.

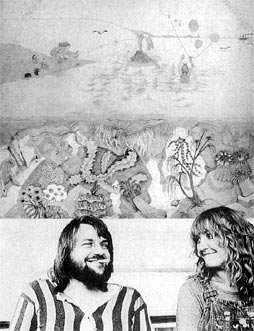

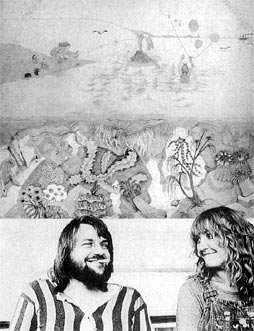

G.P.: How did you and Alfreda meet?

R.W.: Well we met sort of before we knew we met.

She had actually worked at the bar at Ronny Scott's club

in London; for starts I must have seen her quite a lot there.

I think actually I noticed Alfie at the Roundhouse, which

is one of the venues that groups

played in those days. In fact it's the same venue where

we saw Michael Moore. In fact when we went to see Michael

Moore, we went up to the pillar on which she was leaning

when I went and spoke to her that first time. (laughter)

G.P.: (laughter)

R.W.: I just saw her; as it were for the first time.

And she was so different from the kind of charming sort

of stoned wilting flowers around the place. She had a kind

of upright dignity; and kind of like a... I don't know,

she just looked really good to me

and that was it. And the fact that when I did visit her

flat she had the hippest record collection you can imagine!

And it was all right there; Sly Stone, Coltrane...

G.P.: And that tells you a lot right there.

R.W.: Well you know right there I thought "What's

this?"

G.P.: Yeah, you know it's a good sign. That record

collection tells you a lot.

R.W.: Well it's a start; and then she had these art

books of the German expressionists. But mainly she just

looked fantastic. She looked sort of like Jean Seberg the

great actress.

G.P.: Oh, I loved Jean Seberg!

R.W.: Well Alfie was sort of in that mould. I guess

I was the lucky one there.

G.P.: I guess!

R.W.: It's timing they say.

G.P.: Well Robert I've gotta tie it up.

R.W.: Okay. (laughing) Thanks for your interest;

and I think your magazine is extraordinary.

G.P.: I just talked to Terry Riley for the next issue.

R.W.: Oh he's a great man. Please include somewhere

in this my great gratitude to Terry Riley. He was very much

an important part of Paris; and while we're talking about

Daevid Allen. It was though Daevid Allen that I discovered

Terry Riley; and he's been a benign and discreet source

throughout our lives. Say hello to him through this interview.

A lovely man.

G.P.: Okay Robert, well thank you for your time.

R.W.: Okay, it's a pleasure, and thanks for your

interest in me.

| |

Selected solo Robert Wyatt Discography

The End of an Ear (1970 CBS LP)

Rock Bottom (Virgin 26/7/74 LP)

I'm A Believer/Memories (Virgin 6/9/74 single)

The Peel Sessions (Strange Fruit 1974 EP)

Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard (Virgin 30/5/75

LP)

At Last I Am Free/Strange Fruit (Rough Trade

11/80)

Arauco/Caimenera (Rough Trade 3/1980 single)

Stalin Wasn't Stalin' / Stalingrad (Rough

Trade '81 single)

Shipbuilding/Memories Of You (Rough Trade

8/1982)

Nothing Can Stop Us (Rough Trade 3/1982 LP)

With Ben Watt - Summer Into Winter (Cherry

Red 4/82 EP)

The Animals Film (Rough Trade 5/1982 LP)

Work In Progress (Rough Trade 8/1984 EP)

4 Tracks EP (Virgin 1984)

The Wind Of Change/Naimibia (Rough Trade

10/1985 single)

Old Rottenhat (Rough Trade 11/1985 LP)

Dondestan (Rough Trade 27/8/1991 LP/CD).

A completely remixed and revised version of Dondestan

was released in 1998 by Thirsty Ear /Hannibal

A Short Break (Voiceprint 19/9/1992 CD)

Mid-Eighties (Rough Trade 1993 CD)

With John Greaves and others - Songs (Resurgence

1995 CD)

Shleep (Hannibal 9/1997 CD)

Free Will And Testament/The Sight Of The Wind

(Island 1997)

Solar Flares Burn For You (Cuneiform, 2003)

Cuckooland (Hannibal 2003)

|

|