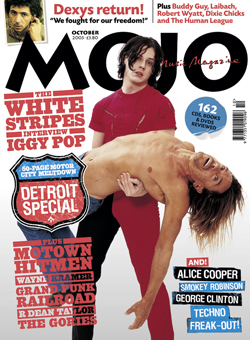

| |

|

Wyatt's first album for six years features guest appearances by Annie Whitehead, Brian Eno, Phil Manzanera, David Gilmour and Paul Weller.

|

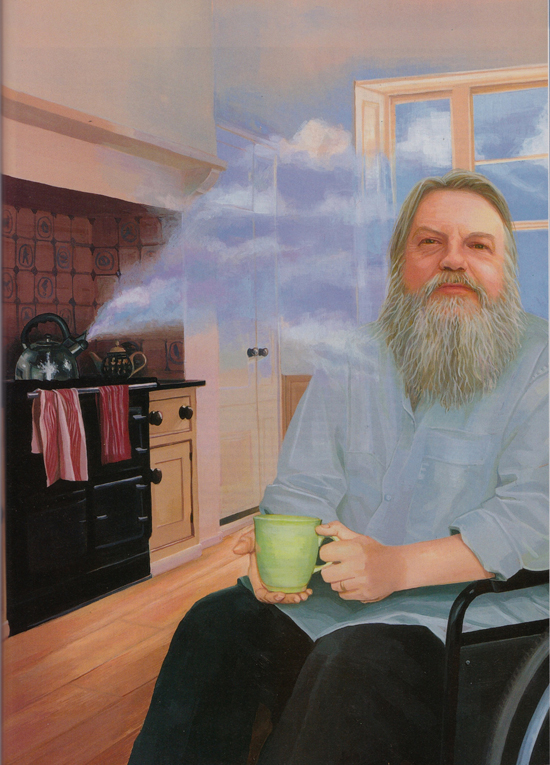

FEW OF the Class of '68 - the year Robert Wyatt made his recorded debut with The Soft Machine — are doing much more than oldies shows these days. Even fewer are actually making new music which stands comparison with that of their heyday — all of which makes Wyatt's achievements with Cuckooland even more remarkable. Winding back 30 years, his tenure as one of Britain's most imaginative and energetic drummers ended abruptly when he broke his back in an accident. This forced him to concentrate his energies into his singing and songwriting — areas in which, fortunately, he was also exceptionally talented. A slow worker but one who has never released a poor record, he has inched forward over hard-won ground to the point where, at the ripe old age of 58, he has made an album which ranks alongside his strongest work. Wyatt's voice, a uniquely affecting instrument which Ryuichi Sakamoto claimed to be "the saddest in the world", still sounds in good nick. Perhaps, as he claims, he has lost a few notes off the top of his range, but his manchild tones ring out sweet and true.

Maybe we should start putting up the bunting and proclaiming Wyatt a 'National Treasure', but somehow you can't imagine that title fitting him too comfortably. True, his work has always been imbued with a generosity of spirit and a chummy, often surreal, humour, but on Cuckooland other equally typical characteristics re-emerge: in particular a profound melancholy and a sympathy with the plight of

those at the wrong end of geopolitical powermongering. Imprisoned Israeli scientist

Mordechai Vanunu, former Iranian leader

Mohammad Mossadegh, the dead of Hiroshima

and Nagasaki and the persecuted gypsies of the

Czech Republic are among those who move through these songs.

|

|

Cuckooland weighs in at 75 minutes, but for those with a limited attention span Wyatt demanded half-a-minute's silence in the middle to allow the listener to "go put the kettle on" or maybe to start with the second half first. Its predecessor, Shleep, came after a similarly long wait, but whereas that album was suffused with a light and warmth, Cuckooland is grainier and grittier, albeit punctuated by joyous eruptions. One of these is Old Europe, a vivid evocation of the Paris jazz scene of the '40s and '50s, including Miles Davis's romance with Juliette Greco, set to a springheeled bop rhythm. Here Wyatt plays drums, trumpet and keyboards, with saxes and clarinet provided by Israeli reedsman Gilad Atzmon.

Back in die '80s Wyatt chose to stop agonising about his limited songwriting output, pointing out that it had never held back Sinatra or Elvis. Cover versions assumed a greater role in his music and, latterly, collaborations with his partner Alfreda Benge have also become increasingly important. Here he tackles a number of songs by vocalist Karen Mantler, daughter of Mike Manlier and Carla Bley. Thee ominous Beware is one of their many vocal duets on the album, with her New York twang providing a satisfying contrast to his Home Counties enunciation. On Cuckoo Madame, Wyatt makes helium-high samples of Mantler's voice flit around his own as he sings Benge's creepy narrative, and the two trade more orthodox vocal lines on a languid cover of Antonio Carlos Jobim's bossa nova classic, Insensatez.

Wyatt has assembled a cast of exceptional musicians here and directs them with a mercurial touch. Although his heavy friends make some telling contributions, the lesser known Atzmon and his compatriot Yaron Stavi on double bass are particularly impressive, playing with strength and sensitivity. But Annie Whitehead is the crucial presence here. Her clear, singing trombone style is a perfect foil for Wyatt's dolorous tones, particularly on Lullaby For Hamza, a song addressed to a boy born just as the bombing of Iraq commenced. Given Wyatt's leftward political leanings one can hazard a guess what he felt about the attack, but this is a wonderful vocal performance. Over a gently bustling rhythm he sings "The world is wrong again, I need your lullaby/Night is long and sleep's just a dream," transmuting any residual anger into a healing song of tenderness and quiet defiance.

Jim Irving

Robert Wyatt talks to Mike Barnes.

Cuckooland seems quite dark in places.

'There have been some worrying events and we do live under what is the most unpleasant government in living memory, and I find that puts a dark grey cloud over the sunniest day, to be honest. Even if I'm not singing about politics it affects my general sense of alienation. I'm disappointed with the way English governments completely cave in to Washington all the time, it just makes me ill. I'm not against real Americans, they don't vote for these bastards any more than we do. So that's where the gloom comes from. Alfie came up with Lullaloop, about an old git trying to get to sleep and thank God she did, 'cos it does lighten it up a bit. But I feel as happy with the album as anything I've ever done in terms of getting stuff out of my head onto tape - it's just a great sense of relief."

Your drumming on this album sounds more flamboyant than it has done for a long time.

"Yeah, for years I was traumatised by the thought that I don't want people saying, 'Not bad for a cripple', so I would just do percussion or no drums at all, or get in a drummer. But more recently I've had the room to leave the top of the kit out and actually you can do quite a lot with a couple of cymbals and a snare, and go into the studio and add a bit of bass drum. I thought: Well, what's stopping me?"

Do you agree with commentators who say that contemporary rock music lacks any political bite?

"I wouldn't think it was fair to single out musicians to have a duty to respond or not respond to things. I don't have a theory about it - if I'm writing stuff, whatever I'm thinking about comes out. Music is music and all I'm really trying to do is make nice sounding records. As Charlie Parker once said, I'm trying to get the prettiest notes in the right order."

Given the success of the Soupsongs tour of 2000 - where your music was played without your direct involvement - is there any chance we might actually see you on-stage in the future?

"Tell, the nearest I got was on the telly thing for BBC 4 -I did a few tunes with Annie's band on that but there was no audience. I like to be a back room person, a cook in a kitchen. I lose my nerve if I have to go out and meet the customers (laughs). Put it on a plate and let someone else take it out. But hearing someone else do something with my tunes is my favourite thing - it's fantastic."

You've described your voice as having being reduced to a "wino's mutter", which alarmed me until I realised it wasn't true.

(Laughs) "Well thank you, that's a relief! I'd rather it was that way round than me saying, Yeah, I'm still singing like a songbird, and then someone says, 'Sounds like a dozy old git to me.' There was a programme on Radio 2 the other day on Nina Simone and I thought, Blimey, this is the real thing. I feel like a molehill looking up at a mountain when I listen to that kind of voice. Luckily, the standards in rock music are so incredibly low that people like me can earn a living."

|

|