| |

|

|

Comrade

Softy - Q N°61 - October 1991 Comrade

Softy - Q N°61 - October 1991

COMRADE SOFTY

|

|

One-time drummer with

The Soft Machine, full-time member of the Communist Party,

Robert Wyatt's life was changed forever by the accident

that crippled him in 1973. But he kept on making music

- just about. "If anything," he tells Martin

Aston, "it helped me with the music, because the

hospital left me free to dream."

"I'M A MUSICIAN when I remember to be,"

Robert Wyatt confesses with an earnest tug at his straggly,

greying beard. "In fact, I don't even think about

it very often. l'm still mainly a jazz fan. If you could

get a job as one, l'd apply for it. 'I want you to listen

to the entire works of John Coltrane'. 'OK boss, sure..."'

Over the years, Wyatt has become accustomed to defending

his periodic absences from the music business. No two

or even three-year between albums hibernation here; give

or take the odd single or collaboration, since 1975's

Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard, it's taken him five years

to release a brace of singles and a film soundtrack, another

four to release a selfpenned album and a further six years

before the new LP, Dondestan, was ready to go.

"Basically, since the mid-'70s, you could say my preoccupations

have been, uh, political," Wyatt sighs, visibly uncomfortable

with the limited connotation of his words. "I've done

things like write articles for the Morning Star on topics

like Bulgarian folk music or foreign radio stations, or,

in the case of my last piece, Courtney Pine. I also write

letters to anyone who'll print them, and a lot who won't.

It doesn't sound like a lot, does it? l've probably turned

into the left equivalent of those anachronistic, retired

generals who dash off furious letters to the DaiIy Express

- except I write to the BBC..."

Wyatt's career would undoubtedly have taken a different

turn had he not, in 1973 , drunkenly fallen out of a fourth-floor

window at a party and broken his back. He'd left his Canterbury

school in 1960 without any qualifications but with an

overwhelming love of jazz - "I used to live precariously

in a kind of reconstructed ' 40s Harlem in my head and

only come out to eat and sleep" - which led him to the

drums and his first group, The Wilde Flowers. They soon

split in half, Pye Hastings and David Sinclair forming

Caravan while Wyatt teamed up with Mike Ratledge, Daevid

Allen and Kevin Ayers in Soft Machine.

|

> Zoom

|

| |

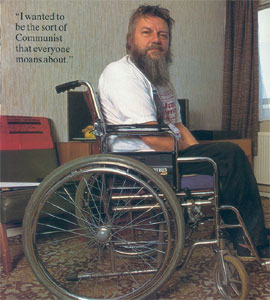

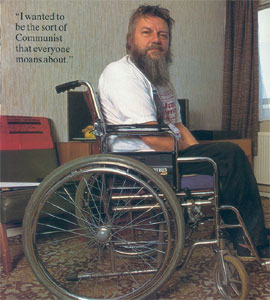

Robert Wyatt

in North London, Summer 1991.

Disabled by an accident in 1973, the one-time

Soft Machine drummer turned his attentions

to singing, to solo records like Shipbuilding,

and to politics. |

|

The Softies, as Wyatt calls them, joined Pink Floyd at

the forefront of Britain's new wave of psychedelic art-rockers,

quickly turning to free- form jazz-rock fusion. But there

were constant tribulations - "The history of the group,"

Wyatt says, "was throwing each other out of it" - and

Wyatt himself finally departed after the fourth album,

to record the largely instrumental solo album, The End

Of An Ear, after which he formed the equally experimental

Matching Mole, a group of "people I could talk to" and

who gave him the chance to sing in that characteristically

affecting, melancholic voice. (When asked now whether

he likes his voice, he dodges the question by self-deprecatingly

referring to one critic who likened it to " Jimmy Somerville

on valium.")

Matching Mole were already exploring Wyatt's melancholy

fusions when his accident occurred, committing him to

hospital for a year and depriving him of the bottom half

of his drum kit when he got out. Unable to maintain a

group from a wheelchair, Wyatt slowIy transformed the

music that was to become the group's third album, ending

up at Rock Bottom, a brave, deeply ironic title for a

work whose vivid, painful introspection and dreamy, musical

landscapes have been compared to those of Van Morrison's

Astral Weeks. "I was just relieved that I could do something

from a wheelchair," Wyatt confesses. "If anything, being

a paraplegic helped me with the music because being in

hospital left me free to dream, and to really think through

the music."

AT VIRGIN Records' suggestion - "because they had

this English idea, that to exist, you had to have a single"

- Wyatt recorded The Monkees' l'm A Believer and found

himself on Top Of The Pops when it scraped into the Top

30. But the follow-up, a cover of Chris Andrews's Yesterday

Man, was never officially released, because Virgin mogul

Richard Branson thought it "a bit too gloomy". Wyatt grins

at the memory.

1975's Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard was a jazzier, eclectic

affair, "more a case of roping in mates in and using their

stuff." The mates included exiled South African trumpeter

Mongezi Feza, guitarist Fred Frith and oblique strategist

Brian Eno, "with his toy machines, desperately hating

jazz," Wyatt fondIy recalls. And then silence. "Remember,

I started out as a drummer and became a singer, because

that was the only thing I could do properly once I found

myself in a wheelchair. l've never been a songwriter in

the sense of doing it all the time. When I have enough

ideas, I start working on them. There has to be a reason

for each record I make."

The reason behind his re-emergence in 1980 with four double-sided

cover-version singles was two-fold. Being chairbound knocked

the idea of the musician's life of travelling on the head,

but paradoxically opened up a broader worldview via books,

television and, in particular, radio, as Wyatt voraciously

tuned in to local, jazz and black music radio and further

afield to stations over the globe. Inspired by his wife

Alfie, depressed and angry about the continuing existence

of apartheid and what he perceived to be the NATO powers'

colonial attitude toward the Third World, Wyatt became

increasingly politicised, which culminated in his joining

the Communist Party.

|

Wyatt drumming with Soft Machine.

"It's

taken me this long to get over not being a

proper kit drummer. Now I enjoy the top half

of the kit."

|

"I wanted to be the kind of Communist that everyone moans

about. I wanted to stick to the party line and see what

I got out of it. I wanted to work more as a party member

who happened to sing than a musician who was dragging

politics into music. At the same time, I came to the conclusion

that rock, as an alternative culture and threat to the

old order, was becoming increasingly hard to take seriously."

Wyatt's covers were a fascinating selection from diverse

cultural contexts but unified by a folk/ethnic base and

spirit of resistance. Caimanera (or Guantanamera, as it

is better known in the West), virtually Cuba's national

anthem, and The Red Flag rubbed shoulders with an American

a cappella tribute to wartime Russia, Stalin Wasn't Stallin',

and a chilling version of Billie Holiday's Strange Fruit.

Compiled to make 1982's Nothing Can Stop Us, and free

of ego, fashion, patronage and sloganeering, the album

is arguably the best political record yet made.

By this point, Wyatt had recorded the Animals Film soundtrack

and relocated to the Catalan region of Spain, primarily

because the light was better for Alfie's painting, but

also as a necessary retreat from Blighty. Not that Wyatt

could keep his distance. In 1983, he was back on Top Of

The Pops with Shipbuilding, with its emotive, Falklands-inspired

Elvis Costello Iyrics.

Complete with a smoky, jazz-trio arrangement, Shipbuilding

was tailor-made for Wyatt's plaintive croon: "They sent

me a cassette through the post because they thought l'd

like a go, which I did. lt was brilliant of them to think

it sounded like a Robert Wyatt song, and not to have met

me and got it so right. I was very moved."

WYATT has always enjoyed collaboration. Working

Week and Ben Watt and Michael Mantler were among his cohorts

through the' 80s, plus Jerry Dammers and the SWAPO singers,

with whom he sang 1985's Wind Of Change single, to spotlight

the South African occupation of Namibia. The following

month, Wyatt returned with Old Rottenhat, 10 of his own

songs which exposed a multitude of sins, two being the

SDP/Liberal Alliance and the US-aided repression of the

Pacific island East Timor. But can political pop stars

make a difference?

"Well, yes. For example, I think the Nelson Mandela concert

contributed something to his release, though it didn't

get rid of apartheid, which is still intact in economic

and political terms. One of the reasons why I got involved

in politics was that I didn't think art, or culture, was

a hammer. I think artists take a much more modest role

as witness. l'm just trying to make a much better news

programme that the ones that keep buggering up my radio!"

Which brings us to Dondestan, recorded

at the start of 1991 near his Lincolnshire home, he and

Alfie having come back to England for medical reasons -

"the Spanish don't know much about aging paraplegics

and l'd rather be near those who are finding out!"

Wyatt still manages to chuckle. And the reason for this

burst of activity?

"Well, it's taken me this long to get comfortable

with being a group by myself, and to get over not being

a proper kit drummer. Now I enjoy the top half of the

kit, and working out bass lines and a way to play them

myself, to make the songs all a piece and in character.

My trouble was that the word part of writing songs hadn't

been oiled for a while, because writing letters or chatting

is quite different to writing Iyrics, which have to be

repeatedly heard. But it occurred to me that Alfie had

written a bunch of poems when we were in Spain, about

the reality of living in a holiday resort out of season,

and the flotsam and jetsam of things in a disorientated

place. So l've sung half a dozen of her poems and tacked

on my usual right-on stuff at the end."

Dondestan is Spanish for "Where are they?".

The title track namechecks Palestine and Kurdistan, while

Lisp Service and Left-On Man both tackle colonialism.

Wyatt starts grimacing for a change. "It's colonialism

a-go-go. All political talk has been about East-West but

l've always felt it was a North-South split, which is the

exploitation of the underdeveloped countries by the developed.

And I got incredibly depressed by the bombing of the Basra

Road during the Gulf War, when everyone was retreating,

and all the euphoria surrounding it. I would like to be

happier, to see news on TV liked, but I can't. I have

to swallow it and then exorcise it."

What Wyatt can, and does, enjoy is his beloved jazz. And

yet he doesn't make jazz music himself.

"No, l'm a gawping tourist of jazz, not a participant,"

he wistfully concludes. "Songs aren't really jazz.

Jazz was my education, but the only thing that sounded

convincing to me was what I do. l'm not a black American

in Harlem, l'm an English bloke born in 1945, so if that's

what I am and what I sound like, then that's what I should

be doing. It's been a long process, finding my own voice."

|