| |

|

|

The Hugh Hopper interview - Canterbury Nachrichten - N° 15 - Winter 1991 The Hugh Hopper interview - Canterbury Nachrichten - N° 15 - Winter 1991

|

|

THE HUGH HOPPER INTERVIEW

"Keep on Caring", that is what Hugh Hopper did earlier that day for his daughter. But before he left, we made this 25-minutes interview: |

F.: Hugh, what was Canterbury like 25 years ago?

H.H.: 25 years ago it was a very quiet place, it was just a small market town, nothing really happening at all. A very strange place to have a center of anything, because apart from the cathedral nothing happened there at all. Then about 25 years ago they started building the university, so things started. More influences came in from outside. And more and more tourism. It's still not a lot of music happening here but it's more an open place than it used to be. It used to be a very small market and country town.

F.: So what differed the Canterbury music scene at that time from the scenes at other towns like London?

H.H.: Well actually I think at the time it wasn't really a much difference. People like Richard, Richard Sinclair and Robert Wyatt and I were interested in different sorts of music, it wasn't just one sort of music we were in, just Rock'n'Roll or so... I mean Robert had listened to a lot of jazz, he introduced me into jazz. But his parents were interested in modern classical music, Stravinski and Varese and all this. I think what it was is that we were open to different influences from outside. Evenings of indian music and ethnic music, so it wasn't just... I think that most other bands that were still playing, were actually playing then in Canterbury were just doing one sort of music. They were playing Rock or Pop or Country and Western or something like that, whereas we were interested in lots of different things.

F.: How did you manage to get this all together?

H. H.: (laughs) That was a great difficulty, yes, it wasn't easy. We didn't play very much to be honest. I mean the Wilde Flowers, which was the first band we started about the end of 1964, and probably in the first year we only played maybe, I don't know, ten, twelve concerts the whole year. I mean, it wasn't a great festival of music. It was quite hard to find enough places to play.

F.: So at that time the Wilde Flowers were just a local band with no international or national meaning, wasn't it?

H.H.: Yeah that's right. We just played around the area, in Kent. I think we played one concert in Essex which is the other side of the river from London, that was it. It was really a local band, some of us had jobs as well and it wasn't professional, wasn't really fulltime professional.

F.: How did the kick come? Now, twentyfive years later, where do you see the point of break now?

H.H: I think probably the break really was in about '66, '67 when the music in England was open to different possibilities. So that when Robert left Wilde Flowers he started up Soft Machine with Daevid Allen. Because at that time there were lots of possibilities of different music, you didn't just have to be a soul band or a jazz band or country and western band. People were actually trying new things, it was the time of Hendrix and all the English bands, different bands, they were trying different things.

It still wasn't easy, it was not suddenly easy to be an avantgarde musican or whatever you want to call that, or experimental. Most people still wanted to listen to the music that had been before.

But in London there were possibilities, the clubs, to play different things. Which was all part of the kind of flower power and whatever hippy-stuff, it was going on at that time, you know.

F.: At that time you were a musician, but for Soft Machine first you worked as a Roadie?

H.H.: It was kind of mixed. It wasn't a clear distinction because for a long time I went to school with Robert Wyatt and we listened to music together and we tried different things, I was playing with Robert and Daevid Allen in London and in Paris just a very few things. We were trying out different things. And then towards the end of '64, '65 I started writing songs. Things like The Beatles were happening and it was suddenly like: O.K. you didn't have to be a jazz musician, you could be a songwriter as well, so I started writing songs.

In fact when Robert broke away from Wilde Flowers they still did some of my songs in Soft Machine, some of the older stuff which is on the first album. So I still connected really. And then there was one point where they needed a road manager and so they asked me if I wanted to do it. So I said yeah, why not. In fact soon after that went on the Hendrix Tour with Soft Machine in the States.

When they were recording the first album it was still Kevin Ayers on bass. But I did some things in the studio, I played a bit of bass here and there. And they were still doing music of mine. And then gradually towards the end of '68 when Kevin had had enough cause it was such a lot of work in America, it was like being at war. You're away from home for years and years and years and he didn't like it, so he left. So the others, Mike Ratledge and Robert, they asked me to join on bass, from then on I was full-time bassplayer.

F.: You just mentioned the connection to Jimi Hendrix. Where there more connections, is it true that Jimi Hendrix played guitar on the first Soft Machine single?

H.H.: I don't know if he played guitar. In fact he and Robert were quite friendly and there are some demos which Robert did after the first Hendrix tour. Robert was actually staying with Hendrix in California and Hendrix actually played some bass on demos of Robert's. Yeah, there was a lot of mixing, things like Robert used to sing, he did some backing vocals on "Stone free", which is on the other side of "Hey Joe", the backing vocal of Robert and there as well as other people. It was a mixture because Hendrix and Soft Machine were in the same Management Company, so they were all friends and if Hendrix was recording then Robert was to go along to the sessions and Mitch would come along to the sessions we were doing.

F.: It was a very high time of Soft Machine with you, Robert Wyatt and Mike Ratledge. But then it flew away somehow. What did happen?

H.H.: The thing is that when it first started, Soft Machine with Kevin, it was a very different band. It was songs and it was kind of part of the whole sixties, late sixties atmosphere, with Daevid Allen. I mean when Daevid left Mike Ratledge became more dominant and he was more interested in composing and jazz and classical music. So it became more structured and more technical. I think that was the change. Robert gradually became less and less of an influence in the band. So the things like songs went out completely, it became more of a sort of a jazz-rock band. So it changed. But I mean it's like all bands, it changes all the time, it doesn't stay the same.

Kevin was only in the band for about two years. I think I was in the band for about four years. And they carried on after I left for about another five years with completely different musicians. There are two ways you can think about it. Either you should change the name completely as soon as the first person leaves, so it is no longer Soft Machine, it's something else. Or you can say it's like a changing group with people leaving, coming, going. I mean it did change, it became more jazzy, more technique really I think.

F.: What happened to you after you left the Soft Machine?

H.H.: The first thing I did I joined Stomu Yamashita who is a Japanese percussionist, played with him, did some records. Then I joined a hand called Isotope with Gary Boyle. Did some things with Carla Bley. Lots of different things really, I play with people in the jazz and jazz-rock area mostly. Made a couple of solo records and then recently, the last four or five years I've been working mostly with dutch and french musicians.

A very good guitarist called Patrice Meyer with whom I work with, he's one of my favourite musicians.

In fact I feel happier playing music now than I was in Soft Machine days because at that time firstly I was younger and when you're younger you are always trying to find a way and it's very hard actually to find what you're really searching for. Also in Soft Machine, when you're in a band which has a certain amount of success then the problem is that you're really there it's like being in a job. It became very much like a job. You know that in six months time you'll he playing in Duisburg or you'll be playing in Paris. And it's really not like when you first start playing music which is: you want to play because you just want to play the instrument or you want to hear the sounds because you love music. But when you become part of a big band then it becomes a business really: You are going to play because you are being booked to play six months before. You may not feel like playing that night.

It's not always had, obviously, but looking back on it now I see that I'm actually happier now than I was then. Because I'm playing when I want to play and with the people I want to play with.

F.: So how did you survive all the time?

H.H.: Good question. I still get some money from things like Soft Machine records. They're all being re-released now on CD which is good. Money from writing music. I mean, I'm not a rich person, I don't have a big car and I don't have a big house so I don't need a lot of money. But I survived.

F.: I heard you worked as a taxi driver?

H.H.: Yeah, for two years I worked in Canterbury as a taxi driver. I havn't done it now for about two or three years. I was so because I was writing a lot. I wanted to be a writer as well as a musician. There are two ways you can do it: You can either look for music work which is not interesting but a lot of money like work in a restaurant, playing music you're not really interested in, which I don't want to do. You just as well might work as a taxi driver because it doesn't interest me to play notes. In fact it's better not to because otherwise you start hating music because you start not even thinking about music, it's just notes. Notes equal money, it's not for me, you know. I'd rather do just a few gigs a year and be interested in the music than do seven nights a week and not being interested in music.

F.: During time your approach towards music seems to have changed. With Soft Machine it was more the jazzy rock-thing, and now you are playing more the rocky jazz-thing.

H.H.: Well, it comes and goes. It's never one thing or the other. There are times when I'm really interested in writing music, there have been periods when I've written a lot. When I work with Richard Sinclair there was a period about eight years ago when I was writing all the songs, the piano writing things a lot of course. I don't do that now, it comes and goes. I'm glad it does, I hate to be sort of the musician who just does one thing, it doesn't interest me. Although it might make more money.

F.: What do you think of today's music scene?

H.H.: There are good things. I mean lot of it doesn't interest me at all. In every sort of music there are like... Most of the musicians and the music is boring it's just copies what's gone before. There is just a very small percentage of people who are creative. And I don't think that has changed even now. It's easy to say it's all rubbish, it's all machine music. But even within machine music there are good things and bad things in the same percentage. It's the same in jazz. There is a loadful of very very boring jazz. Always has been, because people think: Oh, I like jazz, I play jazz but they don't necessarily have the genius to actually doing it different.

That's the same in all sorts of music. Whenever I listen to the radio, if I listen to a pop station there'll probably be one song in about ten that has got something interesting. So I don't think it has really changed. What has changed is you got a lot of technical advances now which we didn't have. When I first started playing most of the instruments playing with you just had to sit down and play. That was actually a physical thing you had to play with. But now you've got the possibilities of writing computer music and sequencers and things like that. So that has changed. But I think it still depends on being an interesting person doing the computer. It hasn't really basically changed.

F.: What do you think of your place in music business today?

H.H.: My place?

F.: You once wrote a song which was quite popular: "Memories", even sung by Whitney Houston on a Material record. You were a kind of pop star for a certain generation when you played in the Soft Machine. What do you think of your place now in music?

H.H.: I think that was almost an accident. I don't think I was ever a pop star anyway. Soft Machine when they were popular it was a lucky period because there was possibilities then to do something that was called progressive music. But for the great majority of people they weren't really interested in Soft Machine. They were still interested in Rolling Stones, Rod Stewart. And I don't think that changed. So I never really fell that I was a pop star. It was no question that we were. We were just a successful jazz-rock band. So in a sense I don't think my position has really changed, I still feel myself to be a very small part of music. It is not really my desire to be famous. It is more important to me just sort of write a good tune or to play a good concert with people.

Of course everyone likes to get paid money and it's nice to have more money than you've had before. But I never really tried to be famous, it's hard to tell though. When you're young you probably think, yeah, I want to be famous. I never felt myself to be in the mainstream of music anyway. It has never really interested me. I think if we were popular it's an accident more than a grant desire. I think that was the answer.

F.: What happened to the other members of Soft Machine, what are they doing now?

H.H.: I still play sometimes with Elton Dean, he's still active, mostly in Jazz, he's playing sax. He has his own band and he plays with Phil Millers Band. Mike Ratledge, the keyboard player, he is very very rich. He's doing music for television commercials and films. But he doesn't play music, he just runs a studio. He is very very successful. He does all the famous TV commercials in England: Renault cars and things like this.

Robert Wyatt is living up in Lincolnshire in the North of England. And in fact he is just being recording a record now which is good because he hasn't been working much. Robert is very... keeps very to himself and doesn't... he's not interested in just being a singer because he's known as a singer. And he wants to sing when he's got something to sing about or write about. So for a long time, I think it's for five years or something he hasn't brought out a new record. He's just been recording recently. That's good. I suppose Elton and I are the ones that are playing most still. Elton is an actual jazz musician and he will always be playing. When he has got a saxophone he will play it.

There have been times when I haven't played at all for a year cause I've been interested in writing and haven't been interested in music for a year. I don't consider myself just as a musician. I can do certain things in music but I'm not a great musician, not only a musician. I'm interested in writing and other things as well.

F.: You just got a new CD out, a live recording with a dutch band, very good jazz music. What are your plans for the future? Making that kind of music with a dutch band?

H.H.: Yes, I think so because I enjoyed playing with them. When that band started, that was another accident really because there was a friend of mine in Holland. I stopped playing for about a year and when I wanted to start again I contacted people to try and get some ideas for places to play. And so a friend of mine in Holland said, well I know this dutch guys who are very good, come and do a weeks work.

And so I did that and it could have been terrible but in fact it worked out well and the band has gradually changed. When it started it was two saxophone players and keyboards, guitar, bass and drums. And now it's just one sax player and a guitarist so it's more jazz-rock than jazz.

That's the band with Patrice Meyer, the french guitarist has settled into that formation and people I like working with. And a keyboard player Dionys Breukers I like working with cause he's not just a jazz musician, he will play sort of samples of different things, voices and sitars. Sometimes he wouldn't play at all in a number, he would just lend aside and let us going which is great because it doesn't mean you always gonna sound the same, sound different. I'm working with that. Also with Lindsay Cooper. Last three years we've been doing the whole Moscow project. In fact it's almost finished and we only did two gigs last year. But we might be playing in Moscow itself in September.

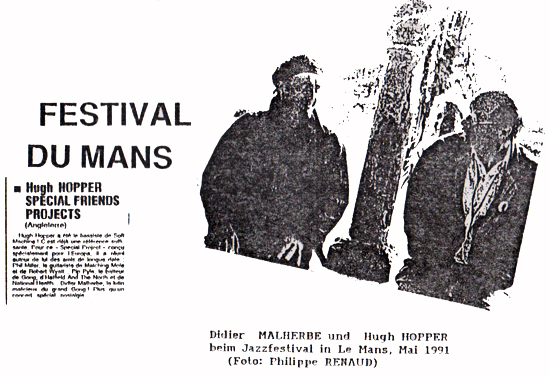

I've also been playing with Didier Malherbe from France. Whoever phones. Whenever someone phones and it sounds interesting I'll play. Always doing things with Richard Sinclair, he's doing a recording project at the moment. He and I have done things in the past, writing songs together and playing together. So whatever happens, whatever the phone rings.

F.: Whenever the phone rings, that's the way musicians usually work if they're not only in it for the money. But what has this all got to do with Canterbury? Is there still a Canterbury scene, is there still a Canterbury music?

H.H.: I think it's a journalistic label... it's a useful thing... I mean I don't mind it but people like Robert, he in fact hates the idea if someone says: Oh, you're a Canterbury musician. He says: No, I was born in somewhere else. He just happened to go to school here. It's true that in the time when the Wilde Flowers started we hardly ever worked in Canterbury. It wasn't till Robert and Daevid went to London to start Soft Machine that anything happened at all. They weren't really a Canterbury band. So it's a usefull label that people have put on it to group together people like Caravan and... The only two bands really that were Canterbury musicians were Soft Machine, but they didn't actually start in Canterbury, it's really Wilde Flowers and Caravan. But it's a useful connection. Even when I play with Lindsay, I never played with Lindsay until three years ago, she was with Henry Cow and things like that. So people think of Henry Cow as being a Canterbury band, but they got no Connection with Canterbury at all. No one of them came from here at all, they came from Cambridge or something like

that. It doesn't worry me, I use it if it helps people understand or listen to more music then it is fine.

I think it's a rather artificial label. Canterbury has never been a really good place to play. I played one gig last Friday and it was the first gig I played here for about two years. It's not virtually a musical place. There are lots of people who've come from it. There are few pubs here, but it's not really a musical hot bet at all.

F.: Is it true to say that Canterbury is a state of mind?

H. H.: Yes, I think that's right. It's a confused state of mind. Canterbury, what does it mean? I was born in Canterbury and I lived here until I was about nineteen and then I lived in other places in France and London, other places in Kent. Gradually came back this way. It wasn't really a plan, I don't know, it just happened this way. Richard is the same. Richard was born in Canterbury, he went to school here and he's lived in other places too, but he's back here. And Pye Hastings from Caravan, he's lived here, but he wasn't born here, he's from Scotland. It's a nice idea because it's a nice little town, it's got a cathedral and in the summer it looks good, it's a nice idea. It's not really much happening here. If you say to me: Well, where is it happening, I got to think: well, let's see, maybe one gig every two weeks.

F.: When will we see you back in Germany again?

H.H.: I hope to be playing in October when we're working again with Patrice and the dutch guys. I don't know how many days yet, we're starting in Holland in October and suppose we'll be connecting with German gigs as well. Also I have friends in Germany which is good, in Frankfurt and the famous Manfred Bress in Duisburg, he's got this fanzine. He's been responsible for a lot of things really because he knows things about me I don't know about myself. He connects that with lots of other people which is good.

It's always been much easier to play in Germany, Holland and France and Belgium than in England and it always was. Even when Soft Machine were at the peak of success. It's much more interest in those countries. In England it has always been very kind of closed. You're either interested in one sort of music or another sort of music.

There are not many people in this country here who are open to different things. I get the impression in Germany and France and Holland particularly that a lot of people will listen to jazz and listen to other things as well. They'll think: I may not have heard this but at least I'll give it a try. But in England the general impression is: I haven't heard it, therefore I don't want to hear it. If I've heard it already I'll like it maybe. People in England are very conservative musically. This is why I hardly ever play here. I used to play in Holland and Germany.

F.: Have you got any contacts in Germany?

H.H.: There's a guy in Essen called Markus Figgen, he works for a production company called Hinkelstein. They are the people who are trying lo get me somewhere in Germany. I think we will be starting working with him in the Ruhr area cause that's where he is, round Essen and other places as well. We did a couple of gigs in Germany this spring. In Frankfurt we played once and right down in the south in Immenstadt, very small club.

I like Germany. I haven't always because I didn't speak German at all until quite recently. I actually started learning german because I felt so stupid not speaking any german at all. Once you can speak a little bit of a language it makes life a lot easier when you feel you're not completely lost. Because in England you usually learn French in schools and you only learn German when you want to. So I actually started doing lessons myself. Deutschländer.

F.: Would you like to say something to the Germans?

H. H.: It is difficult now. Das ist schwer. Dankeschön für... I can't remember it in german, it's stupid, isn't it? Ich habe alle mein deutsch vergessen. Wiederhören, wiedersehen and also bis nächste...

Frank Müller

|