| |

|

|

Not

just different dialects... but different languages - Popwatch

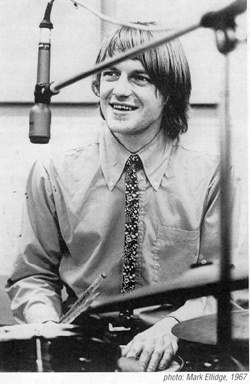

N°10 - Winter-Spring 1999 / An interview with Robert

Wyatt by Dave Cross Not

just different dialects... but different languages - Popwatch

N°10 - Winter-Spring 1999 / An interview with Robert

Wyatt by Dave Cross

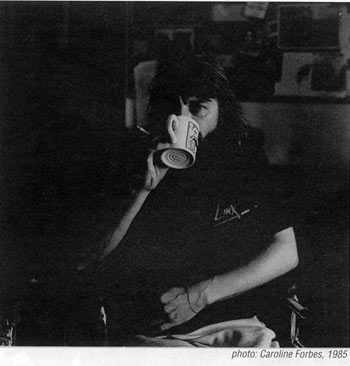

NOT JUST DIFFERENT DIALECTS... BUT DIFFERENT LANGUAGES

|

|

An

interview with Robert Wyatt by Dave Cross

The way he sees

it, there are two different Robert Wyatt.

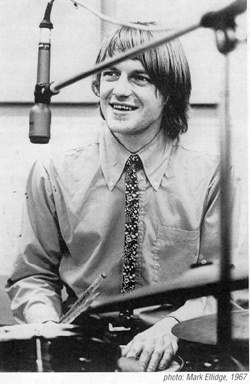

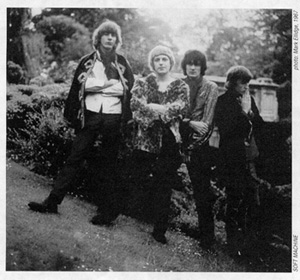

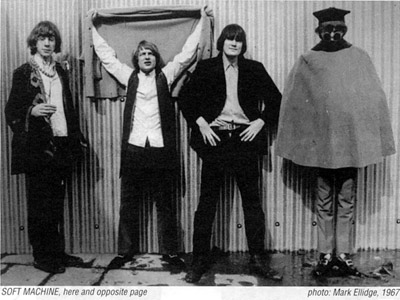

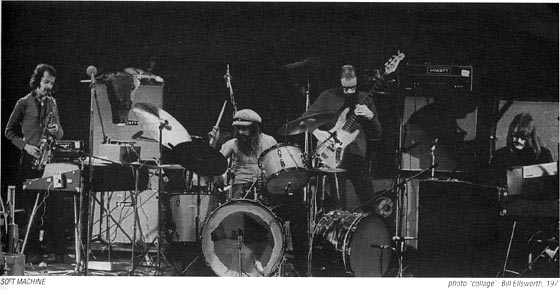

The first was Robert Wyatt the bi-ped. As late-60s guideposts

of British avant garde freak culture, the Soft Machine

had few peers and certainly no rivals. A necessary ingredient

to all great rock bands is tension and infighting, without

which you wind up with a rather bland end product. There

was an overabundance of tension in Soft Machine (whose

great name certainly outlived the effectiveness of the

band itself) and most of those involved can't look back

at their tenure with fondness. Few members of the Softs

ever transcended being a "former Soft Machine member".

Luckily, Wyatt was first and foremost in distancing himself

from his former band - a move that would allow him to

go from flower-child freak to far-left political advocate

with credibility intact.

After being booted his band (still a source of much bitterness

for him), Wyatt formed Matching Mole. At that point, perhaps

not distanced far enough from his former unit (indeed,

the name Matching Mole was a pun drawn from the French

translation of Soft Machine), the Mole was not the greatest

financial or critical success. Wyatt folded the first

version and was in the process of reforming a more compatible

Matching Mole when he fell out a window, breaking his

back, and permanently winding up in a wheelchair.

The second Robert Wyatt emerged in 1974 with the release

of his fully realized lyrical, political, and musical

vision. Although Rock Bottom was actually his second solo

record, by all accounts it was the perfect debut of the

fully mature Robert Wyatt. Intense, harrowing, and introspective,

the record was a critical success, and soon Robert found

himself on the English charts with a couple of successfully,

designed and executed singles. As Robert would later say,

"I'm a girl who likes to say yes".

Soon after, punk rock would rear its ugly head. Rather

than take the reactionary view of many of his former colleagues,

Wyatt embraced the post-punk culture and worked with some

of the leading lights of post-punk U.K. Although it was

never meant to last as a permanent document, Wyatt's work

of the early 1980s is both politically vitriolic ans musically

superb. No thinly veiled political art rock hinting at

Communist orientation, Robert's work for Rough Trade is

direct and personal. It's as if he's singing those songs

just for you; perhaps his most endearing and long-lasting

trait.

There are always long gaps in the recorded history of

Robert Wyatt. It's as if he realizes no one will ever

forget about him, or else he'll reinvent himself to a

brand new audience whenever he decided to return. Whatever

the reason, the 90s have only seen two new Wyatt releases

so far (there were two compilations as well). His latest,

Shleep, is a superb romp through many of Robert's old

musical playgrounds with cutting-edge jazzbos bumping

heads with pop superstar understatement. But don't think

for a second that all the high-profile guest stars or

superbly glossed production can overshadow. Mr. Wyatt

himself. He's the little wizard waving his wand over this

whole alchemic brew; at point it comes off like a digital

retelling of his classic Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard,

other times there are elements of most of his other works.

1998 has been a very busy year for Robert Wyatt. The U.K.

release of Shleep finally landed in the U.S., thanks to

Thirsty Ear. Additionally, Hannibal/Ryko in the U.K. are

readying most of the Wyatt back catalog for reissue on

CD (likewise to follow shortly thereafter in the U.S..,

again on Thirsty Ear).

|

THIS INTERVIEW WAS CONDUCTED ON JANUARY 6,1998.

Popwatch - You play trumpet on your new record, Shleep.

Robert - Yeah.

Have you played trumpet on any of your prior records?

I don't think I ever did, although I seem to remember

playing a trumpet mouthpiece solo, an imitation Roy Eldridge

trumpet mouthpiece solo, on an ancient thing of Daevid

Allen's about being an Australian, called "Fred The

Fish," in about 1966. I always played mouthpiece

at home and I studied it a bit at school, but I didn't

like the music I was being taught and I couldn't really

read the little dots. So I dropped the lessons and, in

fact, left school when I was about 16 altogether. Long

before I was even singing, the ultimate sound in my head

that a human could make was Miles Davis with a mute. That's

always been my favorite sound in the world. And now all

my heroes on the trumpet are dead... I just wanted to

remind myself of some of the sounds of the trumpet. That

was all really.

Does this make you approach composition of melody a

little differently?

I think possibly because that was what I was listening

to that that's what comes out a bit. I'm not a singer

that is obviously influenced by singers. I don't even

think about the art of singing, really, when I'm singing.

I'm thinking about the notes. And when I think about notes

I think about the musicians I like rather than any particular

singers. Although I've got to enjoy some singers more

recently.

It definitely sounds like your took your time on this

new record and really worked it quite a bit, using editing

techniques and other studio features that really aren't

on a lot of your other records.

That's right. It's just that the circumstances were there,

basically. It was just a nice atmosphere being in a studio

run by a musician, who's an old friend as well you know...

and he helped. We were just able to go back and rework

things.

How long did it take you to record this album?

Well, the actual recording time... I work pretty fast,

but it was spread out. I would do a couple of days recording

and then take the tapes home for sometimes a week or two

or more. It was over a year ago... for maybe a couple

of months. About a year ago (1/97-ed.) I was right in

the middle of it I suppose

How was it working with Brian Eno in 1997?

Just the same! He hasn't changed at all. He's just so

fast in the studio. All the particular things that I'm

illiterate about... which is like what the little buttons

on the machine do and so on... he's quick and fast and

very imaginative.

Perhaps he's even quicker and faster now. He gets so quickly

to what he wants to do. He doesn't spend hours thinking,

"Maybe we can do this." He sort of hears something

and calculates an appropriate response, such as the kind

of dripping water sound on track two; he got that in minutes

really, from hearing the track, and it just goes so well

with the cymbal. He just seems to be able to make the

machine do it. Whereas other people can do these things

but they take hours to find the place on the machine.

It's an interesting combination, putting Brian Eno

and Evan Parker together.

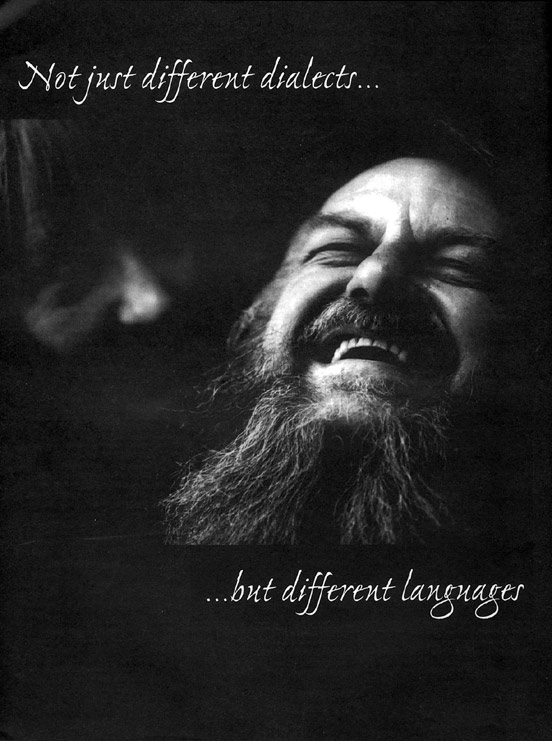

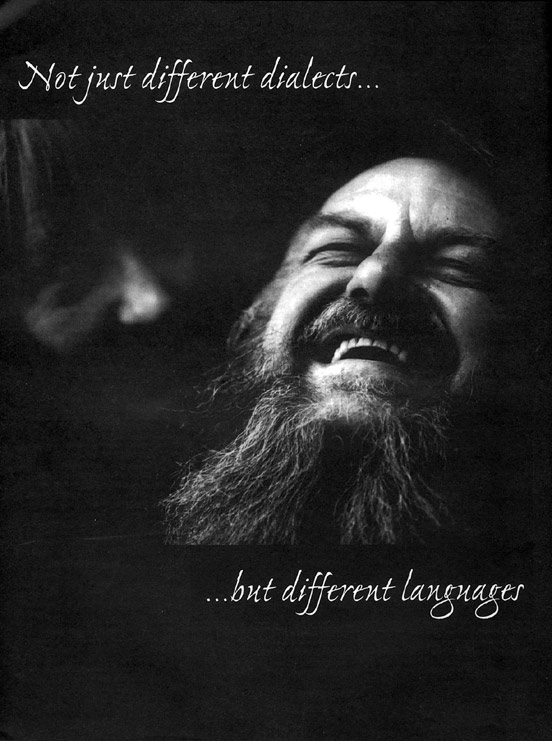

Well they're from completely different disciplines. Not

just different dialects but different languages almost.

But they're both very interested in the idea of not relying

on musical clichés or at least making their own

language.

|

|

|

|

Evan Parker being a huge, huge

European sax giant.

He is indeed. I think he is one of the few non-American

musicians from the jazz tradition who's made a distinct

contribution that you could say is not just participating

in the American tradition.

There are a few, like Django Reinhart, and I think he is

one of those in my opinion.

You work with Paul Weller on the new record as well.

He was recording anyway, on and off, in Phil's studio, and

I left him a little note saying hello really. He said if

I needed any strumming on any songs that he'd be happy to

give it a try.

There were a couple of tunes, particularly the one by Mark

Kramer which I'd altered a bit, "Free Will and Testament,"

and then the sort of Bob Dylan blues thing at the end, which

is really just a blues with slightly altered changes. He

just seemed to feel very comfortable with those. He really

worked hard. I was very grateful because he was right in

the middle of doing his own trio LP, Heavy Soul. It would've

been perfectly acceptable had he said, "I can't think

about anything else right now," but he loves to play

as long as it's serious. He doesn't like fucking about,

he likes to get on with it. I was very honored that he spent

the time for me.

You play with some other old friends on Shleep. Phil

Manzanera makes an appearance.

Yeah, he does. He was sort of hovering about discreetly...

because he knows the studio so well. He also knows my music

better than I do. We have a mutual friend in Bill MacCormick,

the bass player I used to work with. I think they were school

friends, they had a group together before I knew either

of them. So he knows what I do and he knows what his studio

does. He didn't intrude in any way, but he was discreetly

extremely helpful and just made things easier. And he played,

of course, on the only track that I really wrote with Alfie...

that Alfie was part of the actual writing of the song in

the first place, which was " Alien." He played

on that. Alfie is very happy with that solo, which is good

because that was a very important track for us. It's something

of an innovation in the sense that it was a real collaboration.

I mean, the word collaboration is used a lot, but that was

a real one.

Was Alfie in the studio when you recorded that?

Yeah. She actually sort of wrote what the voices ought to

be like. She wanted that effect of accumulating strands,

not in terms of just a choir effect but of loose, accumulating

strands getting slightly denser towards the end. She mixed

the vocals and got the sound on each one... sometimes she

would have a bit of treatment on one word and take it off

the next word. It was very much her project as well as mine

and then Phil just put the icing on the cake.

You work quite a bit with

Alfie on this record.

Yeah, that's right. Well this, in common with the last recording,

she wrote about half the lyrics as well as ideas on the

musical side of how to do things.

You play with another old friend, trombonist Annie Whitehead.

It's funny, because when people think about the musicians

I work with they tend to think about the people in the groups

I was in when I was a drummer.

But in fact, a lot of the people I know best are musicians

that I've known, really, since that period. Since the 7Os

in particular... from being around the little jazz clubs

in London. Annie, like Evan Parker, spent a lot of time

with the African musicians I knew - Dudu Paquan and so on

- and that's really how we became friends. We did actually

record together once, on Jerry Dammers' recording, but I

just really like her. The thing is that she's also a composer

and arranger and I really wanted somebody who could think

a bit Mingus and not just play a solo.

Is writing lyrics something you've had difficulty with

on the past couple records?

Funny... none of the things I am, like being a singer or

a songwriter, I never really planned to be any of these

things. I'm still surprised that that's what I seem to be

and I'm amazed that I still do it. It really surprises me

when I write any songs at all - not that I don't write more.

I'm really grateful to Alfie though. She doesn't write lyrics

as lyrics, apart from "Alien"; she actually writes

them as autonomous little pieces and I tend to just steal

things from her poetry notebooks and sketchbooks and so

on. And that's very useful to me. I have difficulty very

often, working from words to music... that way around...

but in the case of Alfie's things, I've been through a lot

of what she writes about with her. Apart from "Pa in

Madrid" which was, of course, a trip she took with

her own father to Madrid. So I find I can empathize very

closely with what she writes. I mean, I was with her when

the swallows disappeared into the sky. I've watched swifts

with her. I've seen the same little sparrow underneath the

postbox. So it's easy for me to write tunes for that.

|

|

There are a couple of thematic strings

running through Shleep, one being sleep and another being

migratory birds.

Yeah. That's right.

Is it a concept album?

No, absolutely not. A concept album suggests a predetermined

plan, and if anything I think less and less about what I'm

doing as I get older. I'm working more on a kind of infantile

instinct level... just doing what feels right and alive.

I used to be much more theoretical than I am now. I've done

my, sort of, theoretical homework and I know what I think,

and I don't even think about what I think about anymore.

And so it's other people's guess, really, as to how these

images resonate. Their guess is as good as mine.

Are you thinking in terms of recording another album

anytime soon?

Well, I've got bits of more material. It's a question of

not recording more than I can deal with at any one moment

because I like to tackle each song in its own right. Each

song might require quite a different treatment so I don't

want to get into sort of a factory process thing. I've noticed

that with even some musicians that I really like, especially

on the CDs, they just go on and on and on and you feel like

after about a half an hour that that whole way of doing

things is sort of starting to repeat itself too much and

I don't want to do that. So I keep material back. But I've

been asked to do a couple of things for other people which

I'll get out of the way first... before I get back on

to the next thing.

It seems like you're an ideal artist for 7" records.

It's too bad they've gone away.

What do you mean, like singles and things?

Exactly. Like the series of singles you made for Rough

Trade.

Well it's funny that you should say that. Rough Trade has

a singles club, which is a just a subscription-only thing,

where they issue one single a month on vinyl with a proper

packet. A couple of months ago they... although I'm not

on Rough Trade anymore... Geoff Travis at Rough Trade asked

me and Hannibal Records if they could use a couple of tracks

of mine for one of their singles. They used "Free Will

and Testament" and on the other side they put an earlier

piece, one of Alfie's things, "Sight of the Wind"

from Dondestan. And it was just as a single just for their

club, so it was nice to see that. It was very nostalgic.

In the 50s, when I was a lad, you got jazz on singles. There

were Thelonious Monk singles let alone more obviously commercial

things like Art Blakey and Cannonball Adderly and Joe Zawinful

and that kind of thing - you know before Weather Report

he was working with Cannonball - and that merged into some

kind of Nina Simone and Ray Charles stuff and the soul records.

And the best jukeboxes in London... I just loved them for

that and I do miss that.

Do you have any other thoughts on the album?

Only that there are things that I would now do differently.

Brian, for example, sang on the first track, and now listening

to it I would have his voice equal up with mine when he

comes in. And I regret the fact that I don't think my voice

is quite good enough on its own in the verses. That's the

thought I have on that! It's a very simple point but there's

a couple of little bits like that, and I'm also a bit worried

about my drumming as I get older. Having heard some of my

drumming 20 years ago I'm not sure how long that I can get

away with it.

I think you can get away with it for a little while longer.

(Laughs) Thank you.

Has drumming affected your health at all? I hear Rashid

Ali has quite bad tendonitis.

Oh, goodness me. I know Jerry Dammers has that. That's a

terrible curse for musicians. I've heard there are some

ways of dealing with it, but... that would be a nightmare.

No, I don't have any problem with that. I think that what

the real problem is - it's an obvious thing about being

a paraplegic really, or maybe it's not so obvious - even

if you're just keeping time with your right hand there's

something about squeezing the hi-hat with your left foot

which keeps your whole body at one. You know, working as

a single (piece of) athletic machinery. Whereas when you're

just working with your hands, even like playing bass drum

by hand on overdubs of the song, it's harder to get that

organic unity in the playing. It's as simple as that really.

You seem to regret a lot of the decisions you've made.

Well, some people are very good at the actual craft of living.

I seem to spend a lot of time at the wrong place at the

wrong time. Or trying to be harmless and actually fucking

people up a bit, like Alfie's career for example.

Oh no.

No, really, I feel very uneasy and I think it's because

I just can't work it out. There are moments, especially

when I sing on other people's records, say, Hapless Child,

or more recently for John Greaves (a bass player here in

Europe), that if I just did one thing then I could really

get around that. But when I'm working on things then I try

to think like a drummer or a keyboard player or a composer

or a word writer and then I'm just not sure what I'm meant

to be. And I've got an awful feeling that just 5 minutes

before the end I'll suddenly realize which one I should

be (laughs). How I should have approached it all. I wish

we could have a test run - it's an old cliché, I

know. I just feel like we're all in a play on a stage but

nobody's given us a script and there are about eight directors

going around shouting out different instructions. And nobody

knows who's supposed to be on the stage and who is supposed

to be off it, and that's life (laughs).

If we could, I'd like to discuss some of your early band

history. Did the Daevid Allen Trio actually participate

in a multimedia event with Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs

in 1963?

I can't remember that! The thing is there was a lot of interest

around jazz and poetry, that is, poetry, music and effects

and other general things in the early 60s when I was in

school. We got involved with various multimedia events but

I don't ever remember doing anything with Burroughs, certainly.

Daevid himself may very well have done so... he got around

a lot more. I was just having left school and kind of not

knowing what to do then. Daevid himself may have gotten

in much more. I mean he was always moving around a lot.

Going back and forth from Paris and Australia and all kinds

of things. But, no. I consider that period just as an apprenticeship,

in terms of what we were doing, more of a learning period

really. It was like going to a school. Instead of going

to university, because I couldn't afford a proper university

with proper things, I went to a kind of culture university

with people like Daevid.

The next band, The Wilde Flowers, seems to take a step

back. They were more rhythm and blues based.

The Hopper Brothers were very locally based, in a way that

I had never ever been in my head. You know, they were born

and went to school and lived in one town. And they had a

group that played in that town and they used to play, you

know, material of the day that was on the charts that was

do-able, and quite a lot of soul stuff as well. There again

I was surprised, really, because I didn't used to live around

there that often. When I had left them Brian had being trying

to learn some Cannonball Adderly kind of thing on the saxophone

and Hugh had been learning Charlie Haden things on bass...

I came back and they were playing Chuck Berry tunes and

I was as surprised as anybody! It was good fun drumming,

and also socially it was a way of getting out of just playing

in people's front rooms and sitting out in the hall. To

get to play in public was a most incredible youthful discipline,

and to play for dances, even more so.

Your next band was the Soft Machine. Obviously there's

bad blood there.

I'm not going to go on about that, don't worry. I'd just

like to say for the record that when things wind up badly

it's difficult to recapture the hope and excitement that

came before that, because it gets tainted.

How many times did Soft Machine tour America?

I don't know. We spent most of 1968 in America, following

Hendrix around. ln the middle we did a few gigs on our

own and Andy Summers came out and joined us for a little

bit.

What was his role in the Soft Machine?

He just joined us on guitar about halfway through for

a few weeks. I think he was on his way to the west coast,

basically, because he had some friends in the Animals.

Andy himself had been in a band called Zoot Money Big

Roll Band - more or less a kind of a big band soul outfit.

And, if fact, he had been the first person to be generous

towards us in an interview in the press in England. He

was interested in trying different things, away from just

being a rhythm guitarist, so he joined us for a bit but

he stayed, of course, out on the west coast.

There was another guitarist for the Soft Machine for

a while, Larry Nolan.

He was an American lad. He was a very nice bloke... used

to write words for songs. Yeah, I think it was sometime

in the mid-60s, but he went back to America. In the end,

with the guitar business... we never found a way with

guitars. The main thing people seemed to have around that

time seemed to be built around the guitar, whereas the

music we were making and arranging didn't seem to be comfortable

for guitarists. Which is why in the end we didn't have

any.

How did the work on Picasso's play come about?

I can't really remember that. It could have been one of

Daevid's Paris connections. It's simply where artistic

Paris spends its summer and they would all organize various

things, though it wasn't all French people down there.

There were a lot of Americans there who I didn't know

very much about. In fact, Taylor Mead and other people

around the New York Andy Warhol circuit seemed to be down

there as well. I loved Taylor Mead, he was a great man,

very funny... and some other people. It was just that

they needed music. We had already done music at the Fringe

Edinburgh festival for "Ubu Roi," an Alfred

Jarry play, and they wanted musicians that were comfortable

outside the regular song format.

Did Soft Machine compose new material for that?

Yes. Yes, we did.

Did that ever get recorded?

I shouldn't think so. Mostly we played on a beach, in

a big dome - a temporary structure that was built. A geodesic

dome built by Keith Alban, right next to a German beer

festival, I remember. That was a bizarre pairing. We had

no money, we were just sleeping around on the beach, I

think, half the time. Which you can just about do in summer

at the south of France.

Could you put the Soft Machine into perspective for

someone who's never heard them?

Ah. (Pause)

No?

The thing is... I wouldn't use the word "rock"

really. I would say that as a basis we used actual pop

song type music. When you think of rock you think of a

blues-based guitar, sort of getting heavier and heavier,

based in rhythm and blues, and I don't think we were really

anything to do with that. I think we were people who like

improvising endlessly on fragments of pop songs. That's

really what it was, that's the odd combination.

And huge volume.

Oh, it got very loud, yeah. Did you ever hear Lifetime,

Tony Williams's band with Larry Young?

I sure have.

It seems like that was the kind of thing that happened

around that period. In 1968 our rather steep learning

curve - if I can use that very modern cliché - came

from having to open for Jimi Hendrix every night. If you're

playing in front of an audience of thousands of people

who are restlessly waiting for perhaps the greatest rock

performer of all time (laughs), they really get impatient

unless you come up with something. It knocks the whimsy

out of you and you really have to get tough and strong

and get on with it. And so, after a year with Hendrix,

certainly, that tended to be our approach.

Let's talk about Matching Mole.

Certainly there's some similar ideas to the Soft Machine,

but movement in a different direction.

That's right. Yeah, certainly from my point of view. I wanted

to carry on playing drums and I was always looking for friends

to play with. In the end, to be honest, I don't think I

ever found somebody to play with. It may be my fault as

a drummer, maybe I'm not playable with. Maybe I was never

meant to be a drummer. As I'd said, at the end of my life

I'll suddenly say "I wasn't meant to be a drummer"

and the whole thing will make sense, but anyway... What

I was pleased about was that we managed to record a couple

LPs on which we got a lot of ideas that I had, and which

the others had - Dave McRae, Dave Sinclair, and Bill (MacCormick).

It was very democratic in a sense, but with the LPs in particular,

the first Matching Mole record, I was able to anticipate

what I was going to have to do later on my own on keyboards

by doing so much Mellotron on the thing because it was in

the studio. It gave me a better grasp on some of the harmonic

implications of some of the tunes I was trying to write.

This was aIso the first appearance of your politicaI

orientation.

Well I suppose so... in joke form anyway. Although funny

enough, I think there's a couple Soft Machine songs where

I refer to... I don't know what I was trying to say... "If

I were black and I lived here I would want to be (a big

man) in the CIA or the FBI." I don't know what that

was about. I've always thought about these things.

The politicalization actually coincided with getting to

know Alfie. And when I got to know Alfie, there were things

around her flat which I had never seen before. Newspapers

called the Workers Press and so on (laughs). Alfie's father

had been a professor of Libriarianship and had set up Libraries

in Trinidad and Nigeria. Between them, they were able to

show me the other side. To me black culture had always been

another aesthetic phenomena, like Picasso and his sculpture.

I was just very grateful for what I consider the main ingredient

to make the 20th century culture distinctive, which was

the black contribution. In terms of all the music I'd heard

- be it Bartok or Buddy Holly - the music that really struck

me as having both the emotional and intellectual weight

that I wanted was, in the end, Coltrane. So I'd always had

this feeling of great gratitude to black culture and more

and more, particularly in England... England really invented

Apartheid, we distance ourselves from it superficially.

Apartheid was a very European phenomenon, funny enough,

and there were a lot of Africans who made us aware of that.

Somehow you couldn't reconcile the enormous debt to black

culture with the general way that black people were being

treated politically and economically. You couldn't tally

it. You couldn't reconcile it. It was via politics that

I opted to try and make sense of that.

Do you continue to do that?

Yes, I do. I would say of all the illuminations of the way

I think, the most consistently bright light in the dusty

little attic of my brain is based on a few Marxist insights

into the nature of power and economics - of who wields it

and why. I'm not talking about a failed attempt to do anything

about it. I'm simply talking about an analysis of how the

world runs. The political analysis helps to sweep away some

of the mystification which tends to be used by some of the

conservatives to disguise what they are doing in the name

of the church and patriotism and the family and all this

sort of thing.

Let's jump ahead a couple years to Robert Wyatt the Rough

Trade artist and your fierce political agenda of that time.

Right.

To me it is very interesting how the politics of the

80s finally played out.

Well, that would be true of any period. It would also be

true of the 60s for me how that played out. Things have

their life span. As I say, it's one thing that's really

stayed with me. But it's just as you don't have to be a

gospel singer if you're a Christian but you might make a

few gospel records when you become involved in the first

place, then it might just imbue the rest of your life. And

I think this has happened with me with my political stuff.

People always think reactionary means right wing reactionary;

but I think I would call myself a left wing reactionary,

that is to say, as harsh as the climate seems to be in terms

of right wing ideas being sold around and being considered

culturally accept able. I feel the need, not as a missionary

or indeed to communicate at all, but just for my own mental

well being, to kind of correct the balance in my own work.

So during the harshest period of Reaganomics and Cold War

banalities, I felt the need to verify my own separateness

from the actions of my own government at the time. As long

as there was some form of alternative going on in the world,

I would look hopefully at any of these developments. Of

course, in the meantime, NATO and the World Bank Organization

have won the Cold War. There is no one posing a serious

challenge to the western victory in the Cold War. I'm not

a revolutionary in the sense of starting something on my

own. I can support people who are trying - and in there

are people still resisting, I'm always very sympathetic.

But the reality at the moment is the Cold War is over and

our side lost.

I'm going to give you the names of some people you've

worked with. If you could, give me a word or two about them.

There's a lot, so if you get bored tell me to stop.

(Laughs)

Jimi Hendrix.

A gentleman.

(Note from the ed. - OK, so the two-word

answer wasn't such a great idea. It took Robert one name

before he expanded his answers to a length that would give

these folks some justice.)

Mongezi Feza.

This is not one word stuff you know. I feel like - and this

is presumptuous - he feels like an alter ego to me. Someone

I might have been. He was exactly the same age as me and

he was 32 when he died. I almost feel like what I've read

that twins feel when a twin dies. Not that I was that close

to him but that's the feeling I had musically.

Syd Barrett.

Well I thought he was an extremely good songwriter and singer

and I was very happy playing on Madcap Laughs, although

he left the credits off because we were only practicing

in the studio when he recorded it and he didn't want to

embarrass us by putting our names on such a shambles, but

I thought it was very witty. People think, "Was he

mad?" "Was he crazy?" - and I didn't think

that at all. A lot of people were crazy, but not Syd.

Dave McCrae.

He's the only session musician I can think of offhand who

kept his soul.

Laurie Allen.

Laurie Allen's a great friend. There again - Alfie knew

him before I did. And he used to play with the South African

musicians with Chris MacGregor quite a lot. And he was the

first person I thought of when I couldn't play drums. He

would play what I would have wanted to play.

Kevin Ayers.

Kevin Ayers wrote perfectly formed songs right from the

beginning. He didn't seem to have to learn how to do it.

But I think he puts himself down too much. I've heard him

say "The group got too clever/ jazzy/intellectual for

me." He was very much one of the main minds behind

the innovations and fresh ideas for new things that we were

doing in the late 60s. I think one of the reasons he never

became a pop star was he just had too many other ideas to

obtain in the pop format.

Nick Evans.

Oh, Nick Evans... I think he's a math teacher now. He might

even have been then. He's just a totally friendly jovial

Welshman - and being slightly Welsh myself I'm quite happy

about that - and a lovely trombonist. His big hero was Roswell

Rudd, which is fairly appropriate.

Lol Coxhill.

Lol Coxhill is a wonderful musician. I've heard him, I'm

sure, playing tenor. I asked him about that and he says

"Oh no, no I don't do that." He's a very lyrical

player and there again - he's a very good friend. When people

are friends it's hard to say an objective thing like a critic

might want or you as a writer might want. I mean, it was

in his home that Alfie stayed when I was in hospital in

1973 because he lived in the same town as the hospital.

He was so poor then. It's incredible - this man bringing

up his two children on his own. You know that there's an

old saying, "Those who have least give most,"

and in terms of material possessions Lol definitely qualifies

for that remark.

Jerry Dammers.

Well, Jerry Dammers is someone I really miss. He's one of

the people who was actually in the rock star industry who

really did it consciously and did the right thing but kept

it stylish, like Paul Weller. There is a way of doing that.

You don't have to become a pranny. I think he put so much...

he took his stuff so seriously that every penny he made

went into things like Nelson Mandela's birthday party thing

that he organized here - a massive concert with Harry Belafonte

and so on. He really meant all that stuff and he got kind

of lost in it.

I would like him to reemerge and play some more, because

I'd hate to think... He's too young to die, you know? In

fact Carla Bley said to me... when I was feeling old...

she says, "Oh you've got to keep playing. Who do you

think you are a fucking rock star?" (Laughs). I'm talking

about Jerry, you know. He's too good to stop.

John Cage.

Oh, John Cage... the two interesting things about him that

I recall... One was his interest in mushrooms, and I've

since acquired a great interest in the biology of mushrooms

as a kind of missing link between animals and plants in

the sense that they can 't live directly off the earth.

That might seem irrelevant to you. The other interest, I

believe, was chess. In both cases they're studies which

require meticulous indexing. A sort of scientific rigor

in studying them - the very same characteristics he led

the way in throwing aside in music. I think it's funny that

he should still have this love of discipline and indexing

but he stripped it away from music.

You have to be very disciplined with mushrooms.

(Laughs) Exactly, you can't be vague with a mushroom. You

have to know what you've got there. (Laughs)

Gary Windo.

Well Gary was just a lovely tenor player really. I think

he was quite unlike the musicians who were around in England,

he was much more like the Americans and, I suppose, the

African musicians in England. Although he was English, the

fact that he had spent a long time in the States... for

example, he played with Wayne Shorter's brother, a trumpet

player in various jazz things, and was very much part of

the post-Albert Ayler generation. Really, that wasn't happening

in England at that time. The jazz musicians in England were

more, I don't know, just not that anyway... much more academic.

As a consequence of that I've really got on very good with

English jazz musicians, and indeed I can't think of many

who would work with me anyway because I would be considered

too primitive. But not by Gary, and I'm grateful to him

for that.

Mitch Mitchell.

You know, I think he's in some kind of hospital thing in

America right now. He's been very ill recently, so I have

thought about him in the last few years. He's a great drummer,

very important. Hendrix benefited a great deal from having

Mitch. I remember Mitch and I used to listen to a drummer

who was actually a couple of years younger than both of

us but we felt of as a kind of a mentor nonetheless - Tony

Williams. The stuff he was doing when Miles was making the

transition from the earlier forms of jazz to the later ones

that he did. The fact that Mitch had that stuff in his mind

and knew about it, as well as the more John Bonham heavy

rock thing that the English drummers were doing around that

time, made him really perfect for Hendrix. That also gave

me confidence to move around the kit a bit in a way that

I subsequently didn't.

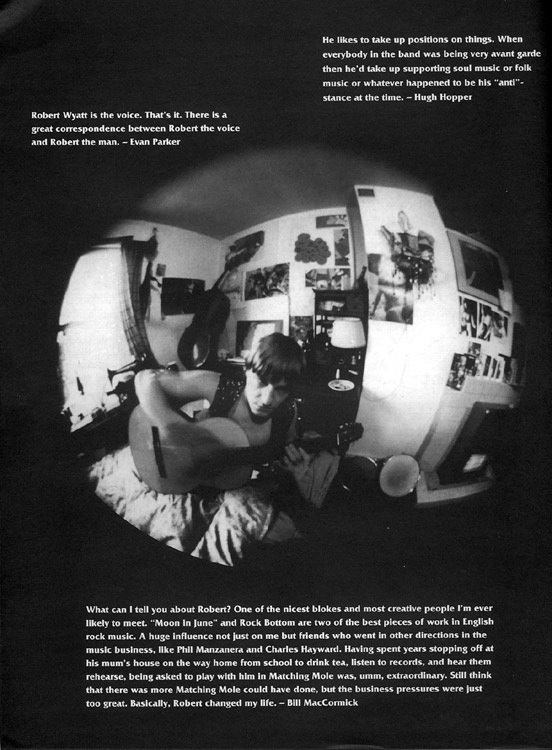

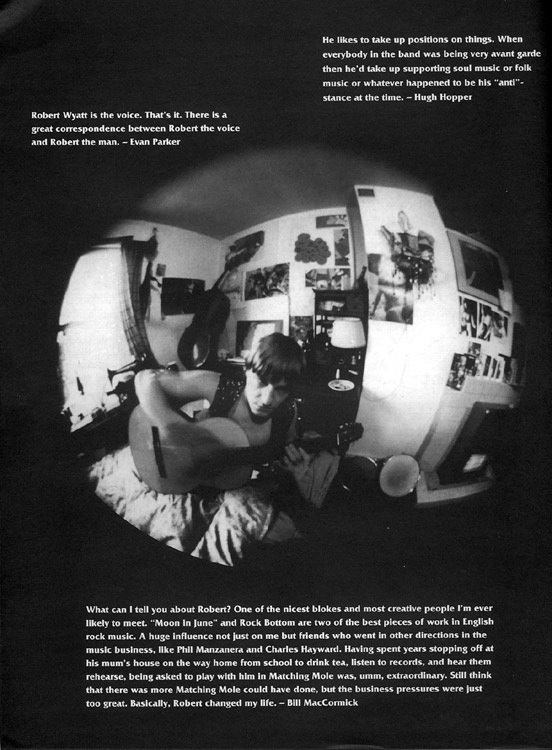

Bill MacCormick.

Well, Bill... yeah. He was a very good bass player. He didn't

play like a bass player, really. He didn't seem to play

the sort of things bass guitarists are likely to play. He

didn't really have a normal bass guitar sound at the time,

but I found his playing very bright and imaginative. He

was always trying to get the most out of things. He was

very good company to have around at the time when we were

very, well, destitute really, and things weren't working

out. Things never worked out with Matching Mole, but he

was always good fun and cheerful and that kept us going.

Richard Sinclair.

He's just an extremely good organ player. It seemed very

difficult at the time for players, especially people playing

the Hammond, to find a way of playing that wasn't simply

based on the Jimmy Smith or Booker T way of playing it.

I think that some of them who did play that way were wonderful,

and in England there were Georgie Fame and Zoot Money who

did so and very well indeed. But he found another way...

much more pastoral, a much more European sound and harmonic

sensibility which fitted the tunes I was working on at the

time perfectly, and I'm very grateful for that.

Daevid Allen.

Daevid. Ah, yeah. Now that's a difficult one. That's really

a long way back. My father didn't approve of him, really,

when he stayed at our house when I was a teenager. I think

the main thing was that he provided an escape route for

me from school, of which I was a total failure. He was a

lot older than us, certainly a lot older than me. And in

the early 60s, maybe even the late 50s, he got a houseboat

in Paris and I went and stayed with him there and got a

taste of what was then the underground focused around Paris

and the jazz musicians there. Various pre-psychedelic people

like Brion Gysin and so on. He opened some doors. The official

doors of schooling had been a total failure in my life,

so Daevid did show me there are whole other worlds out there

to make. You don't have to worry about being a failure in

school.

Daevid is going to be 60 this year.

I think he always was, wasn't he? He always seemed like

he had that guru thing.

Phil Miller.

I think the real thing about Phil was that he really liked

to work on a harmonic thing and chords and so on on his

guitar, and I think that really the most appropriate things

done with Phil was when he had actually wrote the pieces

for which I was able to write songs. It was one of those

periods when I was torn between being a drummer and a singer

in that sense... in the Mole... and I could do it both on

record. Things like the tune "God Song," which

enabled me to write a song that really meant a lot to me

to write, and I couldn't have done it without his music

suggesting the phrasing. I would have liked to have pursued

that side of it more rather than the live things we were

trying to do.

Hugh Hopper.

He was a school friend from the age of 10 or 11, I suppose.

I've always enjoyed singing his tunes, he himself doesn't

sing. He has a harmonic slant on things that I've always

found very compatible with the way I sing. And of course

I'm still singing some of his songs. On Dondestan I sang

a tune of his, I think it's "Left on Man"; and

there again on this LP, "Was A Friend" is a Hugh

Hopper tune. That must be the longest-running musical association

I've ever had, as sparse as it is these days.

Carla Bley.

Oh, Carla's great! This morning I was just listening to

a record, actually by her daughter, her and Mike Mantler's

daughter, Karen Mantler. I love that record. I've got an

LP and a CD by Karen and one of the things is that Karen

has learned so much from her mother - the throwaway irony

of the lyrics, and the meticulously interesting harmonic

developments - she hates a boring harmonic progression and

always puts a little angle in there with a kind of dry wit.

It's a family trait, I think. Carla was very, very funny

to work with. She said, "You have to be tough, if you

run a band in New York you've got to be tough." And

indeed she was extremely tough, and you could see why. She

was very , very witty and had extremely sensible ears. Her

father apparently was a piano teacher. She was Swedish -

her name was Carla Borg before she married Paul Bley. I

had to sing a John Cage song once and it was she who taught

me what the notes were.

Mike Ratledge.

Ah, yes. Well, I can't think of very much there. Too much

blood has flown under the bridge.

Elvis Costello.

A wonderful bloke. He kept his enthusiasm going all the

time when I met him. There again, like Jerry Dammers, he

didn't become a blasé supercilious rock star. I've

never known anybody with such wide-ranging tastes that he

actually did something about. He would work with the Brodsky

String Quartet, he would get Chet Baker into the studio,

he tried his hand at country music. He was just awestruck

by the whole business of music and being allowed to participate

in it.

A very, very nice man.

Lindsay Cooper.

I spoke to her about 2 days ago. Of course I've sung a couple

of her tunes written with Chris Cutler. I liked all of those

musicians very much from the Henry Cow setup, and she was

always very inventive in that genre of playing, and a good

bassoon player. But you know she's very ill now. I don't

know if you knew that.

No.

Yeah. She has multiple sclerosis and, in fact, she's

had it for apparently 10 years. She just didn't want to

face it herself. And then she decided to sort of say it

because she was having such difficulty doing anything. So

she's now, as it were, come out with it and has let it be

known, so it's alright for me to tell you. I'm very pissed

off about that because she can't really function as she

did at all.

Fred Frith.

There's a side of Fred that I would have really brought

out more. I would have really liked to worked with Fred

in a group. I think that if I had found him earlier we could

have been in a late 60s group together somehow. Some sort

of Henry Machine or Soft Cow or something.

Soft Cow.

(Laughs) Because there's something wistful about meeting

someone I felt so compatible with, almost at the end of

my career as a drummer or as a group musician. But still,

I enjoyed singing with their band, and now particularly

I'm having to listen through lots of stuff of mine because

it's being reissued by Ryko, and some of it's lasted better

than others. At the moment some of the stuff I most enjoy

is the duet with him on piano doing his tune "Muddy

Mouse/Muddy Mouth" on an LP I did called Ruth is Stranger

Than Richard in the mid-70s. It's just wonderful how lyrical

it is. He could easily have any kind of career apart from

the, kind of, post-Derek Bailey career he has chosen.

Pye Hastings.

Blimey, I haven't heard that name for a long time. There's

the brothers of course, him and Jimmy Hastings, the saxophone

player. He was a fine musician. He was never amateurish

in the way he played guitar. He didn't seem to go through

that period like the rest of us went through, I think, perhaps

having an older brother who was a superbly schooled musician.

Actually, there's a session musician who never lost his

soul - another one to add to the short list - his older

brother. But I haven't heard from Pye or had any contact

with him for decades.

Brian Eno.

Oh! Brian Eno... well, yeah. just a good friend - really

helpful. What can I say? He's helped me out of some difficult

things. Like a couple of years ago all the microphones I'd

had for 20 years, they all started to pack up, and it was

Brian who sent me a permanent loan of really good new ones

for me to work at home on. Things like that. So he's not

just knowledgeable, he's sort of generous like that. He

likes to help things happen.

Elton Dean.

Elton. Well, the thing is... I remember hearing him with

Keith Tippett's band and asked if I could borrow their front

line for the group in 1968 or 1969. But it was, in fact,

him that got me kicked out of the Soft Machine because he

didn't like the singing, I don't think, and he didn't like

the more heavy side of my drumming. He wanted that sort

of free jazz thing. Well, I had been listening to free jazz

in the late 50s and early 60s and I didn't want to do that

again. But he got the others to out-vote me and to get rid

of me. So there again, it's a bit similar to the previous

question about the organist.

Nick Mason.

Yeah, well, drummers often become friends with drummers

of different groups... and there's no exception there. The

Pink Floyd did a benefit concert for us when I had my accident,

and sort of to return the favor - I mean, I couldn't return

the favor - but I invited Nick to sort of produce Rock Bottom

and we became good friends at that time, him and his wife,

Lindy. We used to go see them and we developed some mutual

friends like Carla Bley and Mike Mantler, who we also did

things with later, and in fact when they did a record together,

called Fictious Sports, they asked me to sing the tunes,

and I really enjoyed doing that. It was very nice to be

on their record and to just sing something without having

the responsibility for the rest of the band.

Michael Mantler.

Well, Mike got us to sing... I think Carla sent him a copy

of Rock Bottom and said "Here's a singer we can use."

I don't really know how it happened, but that gave me the

opportunity to sing with the most transcendental rhythm

section I could have imagined which was Jack Dejohnette

on drums, Steve Swallow on bass, and Carla Bley on piano.

I doubt if I'll ever work with a better group than that.

Evan Parker.

Evan Parker is one of the few European musicians who've

taken an extended line of late Coltrane and turned it into

a whole new thing... both on tenor and soprano saxophone.

Although with his music he sticks very firmly to a serious

line of approach. He himself is a very eclectic listener.

Which is why I didn't feel too nervous about asking him

to play on my record.

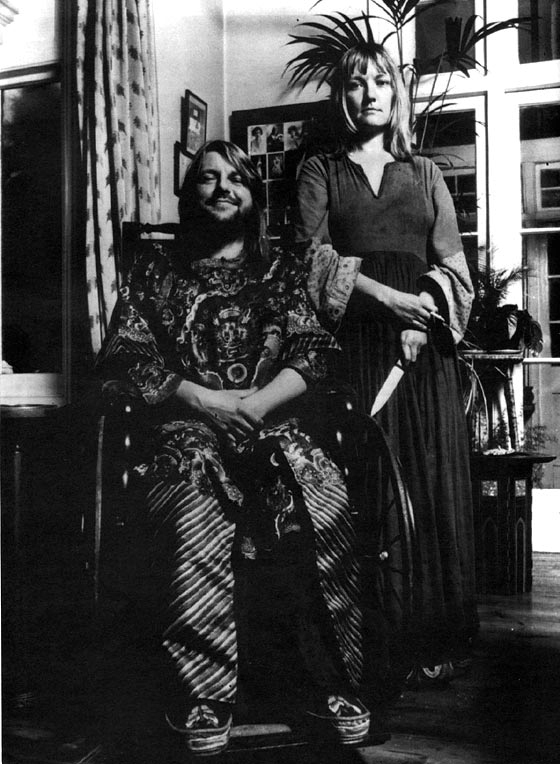

Alfie Benge.

What can I say? She's sitting here. (Laughs) Well, we've

been together since the early 70s - I think that, really,

we are a group. People think I've been in two groups, but

in fact I've been in three. The longest lasting one, the

one that's really worked, has been me and Alfie. In every

possible way. And when I say every possible way that's exactly

what I mean. So, there you are.

While it may be perfectly clear to

many people who Robert Wyatt is, far fewer have a clear

understanding exactly who Alfreda Benge is. Before you even

listen to a Robert Wyatt album you first have an impression

created by the accompanying art. From the debut underwater

seascape of Rock Bottom to the dry abstract expressionist

deserts of Old Rottenhat and Work In Progress right through

to the ultimate slumber/dream accompaniment of his excellent

current endeavor, Shleep - all have had superbly executed

visual echoes of Robert's musical worlds, and all were created

by Alfie Benge.

Sadly, in pursuit of the bigger picture, Alfie has let credit

slip where credit is due; many of the older CD issues of

Robert Wyatt albums feature little or no documentation as

to where the source art originated. Hopefully, this will

deservedly be rectified by the current spate of reissues

by Hannibal/Ryko/Thirsty Ear. If not, perhaps this will

help shed some more light on the subject.

I didn't ask Alfie if she has done other interviews, but

you can bet that she probably hasn't done very many...

|

|

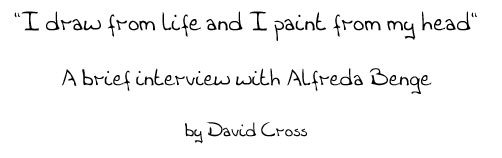

PW - You've done illustrations

for a children's book?

Alfie - Yeah. Two children's books, which are out

of print now. Ivor Cutler wrote the stories. Do you know

of Ivor Cutler who's on the end of Rock Bottom?

Yes. How did that come about? Did he approach you with

that?

Yes. He suggested to his publisher that they see my paintings

and so I went along and showed them my work. I was going

to do four but, in fact, it took 6 months to do each of

them and in the end my eyes almost closed with straining

because they were so tiny... tiny paintings. I ended up

just doing the two: Herbert the Chicken and Herbert the

Elephant. (Laughs)

So he lined it up with the publisher.

Yes, he had worked with quite a few illustrators in the

past but they were usually ones that were known to the publisher,

so he suggested that I may be able to do it. He's a very

encouraging person. He gives people confidence; he tells

you you're wonderful and makes you believe you can do anything.

It was not what I'd been used to because obviously making

24 pages match each other and all of the people look the

same and inventing characters is not the same as doing one-off

paintings, but I was very pleased with them. I think they're

rather good. But like all these things, poor ducks, they

go off the shelves. I still get a few pennies every year

from libraries. So they exist somewhere, but they're unbuyable.

They don't exist anymore.

When did you do those?

Round about '82. The beginning of the 80s... and the next

one in '83 or something.

Did you do much illustration other than that?

Other stuff... yeah. I did a bit for a magazine called Time

Out... a few things. Obviously Robert's covers, a couple

of Fred Frith covers, an Annette Peacock cover... I was

trying to be a painter, so it wasn't a career that I was

after. I can only really do things if I can connect with

them. I mean, I couldn't do a cover for the Rolling Stones.

I'd have to know the person and know their inside really.

Have you made some films?

Well, I went to film school. I had a long art school history

- I did painting, then I did graphics, then

I went to film school. Obviously at film school I made films.

After I left school I had an extraordinary job called Films

Officer at IBM, which was a strange thing for me, and if

you knew me you'd think it was really strange. And then

I did a bit of editing here and there, just before Robert's

accident. In England, to work in big stuff at the time you

had television or industrial films and quite boring things.

I did do one film for the BBC at the end of my student days.

I was paid for a half hour thing. And then I got a job as

a third assistant editor, which is just basically writing

down numbers on "Don't Look Now," a Nick Roeg

film with Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie. But I was

just in the cutting room and that was going to get me my

union ticket which was quite hard to get in England at that

time. So it meant you were much freer to get good jobs.

That was in Venice - Robert came with me and wrote Rock

Bottom there. Not long afterwards he came back and had his

accident and I had to decide what to do... throw him in

the river or look after him. At first he wasn't as independent

and obviously needed looking after. So I thought the film

industry is a bit of a racket, really. I'll give it up...

and I hadn't done any painting for about 12 years and Robert

said "Why don't you do the Rock Bottom cover?"

and that started me back on painting, which I could do at

home. So I had meant to keep carrying on in the film industry

but gave it up. But last year I did a tiny, sort of, job

of rewriting some dialogue in an Aaron Rudolph film. Do

you know Aaron Rudolph?

No.

He a sort of protégé of Robert Altman. Occasionally

I get dragged back to do little things, basically by Julie

Christie, who's my old friend, and she finds things that

she occasionally needs me for.

For Robert's covers, what one's have you done?

I've done everything since Rock Bottom except the "Shipbuilding"

cover. I remembered Stanley Spencer's wonderful painting

and thought nobody could do it better than that. And it

turned out we were able to use it for nothing so... apart

from that, I've done them all, except for the compilations

that have been out of our control

You've worked in a couple different mediums on his covers

too. On Nothing Can Stop Us it's some sort of graphic illustration.

It was just a pen drawing. Rock Bottom was pencil, Ruth

and Richard was gouache, and then the rest have been oils.

They're all oil paintings now. I did graphic design and

typography and that kind of stuff, so I really enjoy doing

things which are more abstract. Where you're using space

and things.

That's one half of what I can do and the other half is strange,

narrative pictures with people and stories and goings-on

in them. Also, I do very uncharacteristic charcoal drawings

which are quite... stronger.

I mean, I draw from life and I paint from my head, basically,

and the drawings don't look like mine at all. That's the

range, really.

Do you paint specifically for a purpose or do you paint

for the sake of painting?

My dream would to be able to paint for the sake of painting

all the time, but life gets in the way most of the time...

either crisis or something else to do.

When Robert's working I'm also his manager, so I have

to do incredibly dull things like the accounts and arguing

about contracts, and I'm also his roadie, so I have to

get him from A to B. I'm also his nurse, and things in

the world happen which need shouting about and you have

to go about shouting, protesting about them. So, I get

dragged away from the idea of just painting. I mean, if

I had a wife I think I'd paint more, but I haven't got

a wife.

I was very grateful to CBS, I have

to say, for the opportunity to go into the studio and make

an album. I don't think they realized that I was going to

make a totally improvised album like that, and I didn't

get invited back. One of the things that mucks up some of

the earlier memories is that we didn't get any more money

from those early records at all. None of them. Our managers

were total crooks and since they are dead I can name them:

Mike Jeffries and Chas Chandler. I mean they just took everything.

The record companies were no help, they seemed to close

rank with managers rather than see musicians go their dues.

In my real life I don't remember much peace and love in

the music industry era at all. Having said that, I was very

happy to have the chance to record, there again, to play

piano and do my little Cecil Taylor impersonations. I think

everybody should have a got at their Cecil Taylor impersonations.

In my mind, if I ever made a transition from adolescence

to adulthood it was by that record. People think it must

have been a very tragic period of my life, with breaking

my back and all, but 1974 was the happiest moment of my

life. The record came out, it came out how I wanted it to

come out, it was made with friends. Alfie married me on

the day it came out, which was a disgracefully self-sacrificial

thing of her to do, but made me feel great.

|

RUTH

IS STRANGER THAN RICHARD

|

On that record I wanted to give the musician I was working

with more space to do their own thing. I set up "Team

Spirit" as a tenor solo for George Kahn.

And there again - I got Fred Frith to play some of his

own tunes - still some of the favorite things I've ever

recorded actually, "Muddy Mouse/Muddy Mouth."

In fact, before doing those tunes he played this note,

I can't remember what it was, some sort of high D or even

an E flat, and I said to Fred, "I can't sing that,"

and Fred says, "Yes, you can. Your range is from

a low F to a high F#." He listened to my records

and knew exactly what notes I'd hit on various records

and told me I could do it, so I had to do it.

This wasn't intended as an LP. Virgin

was very angry with me when I disengaged myself from them

and they threatened us not to make an LP or there would

be legal trouble. While Geoff Travis at Rough Trade was

trying to sort that out and placate Richard Branson, they

allowed us to make a few singles, which is what I did. And

it allowed me to sing some songs by people like Violetta

Parra and so on... that meant a lot to me. But I did them,

more or less, as a musical journalism. I didn't feel these

ideas had to last forever. It was Geoff Travis's idea to

put them together onto an LP.

|

THE ANIMALS FILM SOUNDTRACK

|

Julie Christie had been invited to do the narration on that

by Victor Shoenfield, who made the film. They had asked

the Talking Heads to do the music. They used one song of

the Talking Heads for the opening credit tracks and it cost

them 500 pounds. Well, since the budget for the whole film

was just a few thousand pounds they couldn't afford them

for the whole score. Julie said "I've got a friend

who'll do it for really cheap." And it's true; one

thing I'm really proud of is I work cheap. Geoff Travis

at Rough Trade once said "you may not be the most successful

or the best musician we've ever had here at Rough Trade,

but you're certainly the cheapest." And indeed, I did

the rest of the film score for 100 pounds. They wanted it

released to help publicize the film and that's what I did.

I think making music for films is very good because you

have to break out of the normal song cycle structure. The

structure is given to you by the film. There is a structure

but it's quite different and that makes you do things quite

differently. I know Miles Davis had the same breakthrough

when he did music for a French film, "Lift to the Scaffold."

I really appreciate how useful that would have been for

him when I was doing the Animals Film.

That was done when I was very isolated from other musicians,

although I felt very at home spiritually with the musicians

of that era, perhaps even more than with the musicians of

my generation. The post punk people in England who were

dealing in extraordinary surrealist combinations of punk and reggae and using

old ska rhythms. There was a lot of great political music,

like Jerry Dammers and, indeed, Paul Weller around that

time, but musically it was very different from me because

it was very guitar based and I come from quite a different

line of thought musically. So I found myself, more or less,

on my own and working as a kind of miniaturist there - just

trying to get distilled, pure song on it. And as political

as the songs are, the main exercise was really an aesthetic

one. To try and to get essential song. Just to see how you

could pare it down to that point. I'm also interested in

artists in other fields in that way. Whether it's Samuel

Beckett in writing or Mondrian in painting, it's a very

interesting exercise... to try and pair things down like

that.

Dondestan was after we left London

and came to live up north of England, quite near the coast.

We had spent some time in the 8Os in Spain. England was

a difficult place to be, so we took any chance we could

to go away. Alfie had written quite a lot of poems in Spain.

I think there's something about sitting in a Spanish cafe

in an out of season holiday resort with a glass of brandy

in front of you which brings out a little poetry in Alfie's

soul. Especially with the flamenco posters on the wall.

So that provided the basis for Dondestan. One of the possible

titles for the LP was based on a Cuban film called "Memories

of Under Development (Memorias Su Desorio )," that

was nearly the title of the first track anyway, and a lot

of it has to do with that sense of underdevelopment and

dispersal. Not in the third world, but right among us.

I had a rough period in the mid/early

9Os, musically speaking, and there were some problems here

at home as well. I mean, I don't like people to go on about

their problems because it's boring... but I broke my legs

here in 1993 or 1994, I think, and had to spend some time

in the hospital. I fell out of my wheelchair... so those

kind of things delayed my activity somewhat. But as much

as I get the exact sound I want when I'm on my own I get

lonely, and music is a social act in the end. I was very

happy to be reminded of Phil's studio and I went because

it's near enough London where I can phone up people like

Annie Whitehead and Evan without feeling that they had to

spend 5 hours on a train to get to the studio. There again,

I started exactly the same as I did with Dondestan. Which

is, taking half a dozen pieces from Alfie's poetry notebooks

and working on the music from that and then carry on with

that momentum and finish it up myself.

|