| |

|

|

8

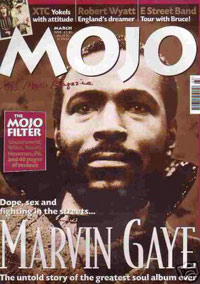

out of 10 cats prefer whiskers - Mojo N°64 - March 1999 8

out of 10 cats prefer whiskers - Mojo N°64 - March 1999

8 OUT OF 10 CATS PREFER WHISKERS

Home

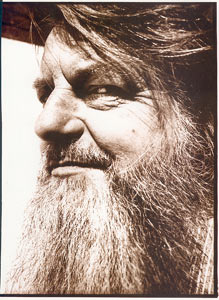

Counties jazz fan, psychedelic Heath Robinson, protest

caroller and musical internationalist, Robert Wyatt is

one of Britain's best-loved institutions. "I'd have

to be some kind of paedophile to be that interested in

youth culture," he tells

Barney

Hoskyns.

'"I'm a bleedin' grown-up."

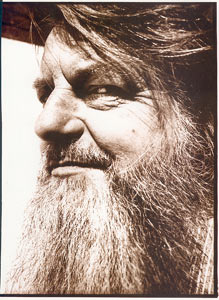

Portrait by Peter Anderson.

THE DAY BEFORE I DRIVE UP TO Lincolnshire to interview

Robert Wyatt, there is a march through the streets of

Santiago - a procession of relatives of men and women

"disappeared" years ago by the regime of General

Augusto Pinochet, the former dictator of Chile. On this

march, every wife, mother, and brother clutches a placard

bearing a picture of a disappeared beloved and the simple,

stark question, "DONDESTAN?"

I bring a newspaper photograph of the march to show Wyatt,

who in 1991 released a quietly militant masterpiece called

Dondestan - and who, as might be expected, is following

the current Pinochet affair with keen interest.

"There you are!"

he exclaims as he peruses the photograph. "And people

think I make these words up! When I told people Dondestan

meant Spanish for 'Where are they?', they didn't really

believe me."

Although the song Dondestan itself concerns Palestine

rather than Chile, the new five-CD collection EPs By

Robert Wyatt does feature Wyatt's version of a heartbreaking

song by one of Pinochet's most sainted victims. Victor

Jara's Te Recuerdo Amanda, translated in the box set's

booklet, is an exquisitely simple sketch of a woman, radiant

with love, rushing to meet her lover on his five-minute

factory break. Except that her lover turns out to be a

man who "left for the hills / Who never did any harm

/ And in five minutes / Was destroyed...".

"Talk about brave protest singers," Wyatt almost

shudders. "I think that's about as brave as it gets,

really. And there's great pathos in singing about a disappeared

person and then becoming one yourself. So it's pretty

timely."

I ask Wyatt and his wife Alfreda Benge - the "Alfie"

who has long been his caretaker, collaborator, and muse

- if they think Jack Straw will let Pinochet go home.

"I was gonna bet with Alfie that he'd want to stay

on the right side of Spain," Wyatt says. "But

now that the White House has spoken and said send him

back to Chile, I think that's what he'll do. There's no

question in my mind now".

Straw will prove Robert and Alfie wrong, but one can forgive

these former card-carrying Communists for a certain ingrained

cynicism about the cosy relationship between Blighty and

Uncle Sam.

l never do get to ask them about the blitzing of Iraq

that follows two weeks later.

|

|

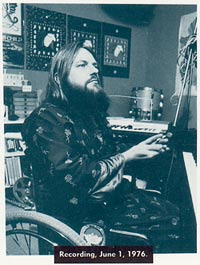

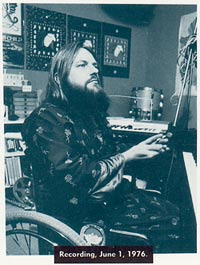

The release of EPS by ROBERT WYATT

is the final chapter in the reissuing of almost alI the

recorded work by this English master, a paraplegic with

a Marxian thicket of beard and the sweet, doleful voice

of a chorister. Comprising such Wyatt projects as the 1983

EP Work In Progress and an edited version of his 1981 The

Animals' Film soundtrack, the box ties up alI the loose

ends of the man 's mercurial career, including his 1974

Top 30 hit version of The Monkees' I'm A Believer and the

1983 Top 40 hit version of Elvis Costello's Shipbuilding.

EPs also features remixes of tracks from 1997's acclaimed

'comeback' album Shleep, a serene, playful collection

that chose the personal over the political and returned

Wyatt to the murky dream-states of his post-Soft Machine

classics Rock Bottom (1974) and Ruth Is Stranger

Than Richard (1975). As a fan of the spartan, one-man-and-his-Casio

loveliness of Old Rottenhat (1985) and Dondestan

- and of the wonderful Rough Trade '80s singles collected

on Nothing Can Stop Us (1982) - I was initially thrown

by the spirit of collaboration that brought people like

Paul Weller into the Wyatt frame. But in time I came round

to Shleep as one comes round to everything this sharp,

big-hearted man has done.

When I finally locate the house in the unspoilt Georgian

town where Robert and Alfie live, I find them leafing through

a dictionary of Esperanto in their dining room. Wyatt is

trying to find a title for his next proper album, and Alfie

is suggesting musical terms to look up.

"What's 'strum'?" she asks as she disappears into

the adjoining kitchen.

"It's ludate, which is rather nice. "

"Look up 'sing'," says Alfie, out of view.

"I did. That's kanti."

"'Hum'?"

A pause of several seconds.

"Hum itself is zumi. That's very nice.

That's good, isn't it?

I was going to call the record Humdrum, so if I now

look up drum... Timburo? Tamburo? That's aIl

right, I suppose."

The Wyatts have been in Lincolnshire for 10 years. Prior

to that, they'd been wedged into a flat in Twickenham where

Robert never had any space to work and into which friends

would drop at aIl hours. One day Alfie set forth and drove

as far north as it took to find a house for the price that

the Twickenham flat was worth. "This house simply worked,"

she tells me. "It was somewhere we could go out and

get everything with the wheelchair. It's quite hard to find

a place like that in a place where you're not cut off and

imprisoned. Of course you miss culture. This is a total

culture-free zone. No films, no art. Once a year there's

some jazz in Grimsby. If we hadn 't got a Tardis full of

entertainment that we've gathered along the way - books

and videos and things like that- it would be a desert island,

really. "

Alfie says the worst was when the Gulf War broke out and

she was on her own here. (Wyatt was in the studio working

on Dondestan.) "I was watching it aIl happen

and it was so frustrating not being able to express your

disgust and anger in any way, because the town went on as

it was before and nobody talked about it. In London you

could have gone out and sort of stood somewhere with other

people. On the other hand, we're the right age where we

know what we need and we've had our stimulation and our

adventures. God help any child that's brought up here without

any access to the Science Museum or anything else."

"The ones that worry you," chips in Robert, "are

the ones who are brought up in Lincolnshire as children

and then go on to become Prime Minister. Then you really

see what the pay off of that deprivation is."

Given that the Thatcher years coincided with Wyatt's most

trenchant musical statements about exploitation, imperialism

and the like, this seems a suitable moment to ask him if

he is dismayed by pop's wholesale retreat from political

commitment.

"Ooh, that's difficult," he says, wincing slightly.

"I'm not a sociologist, for a start. And I never felt

that anybody ought to do anything at aIl in that

regard. I was always pleased when people - Jerry Dammers

or Paul Weller - got stuck into an issue, because they didn't

talk obscurely. But l'd have to be some kind of... paedophile to be that interested in youth culture! l'm a bleedin' grown-up.

I listen to grown-up music."

|

|

|

|

MOJO : You've talked about how hard

it is to fight against the "ideological soup"

that is the centrist politics of Blair and Clinton. Was

it easier to shout out against Margaret of Grantham?

Thatcher was exorcism for me. The other night we were

watching Harold Pinter on telly being asked about this

transition he made to where he was overtly and directly

engaged politically, where there were goodies and baddies.

He said he was traumatised in the early '80s. He was stifled

by the climate. . . suffocated was maybe the word

he used. You fight your way out of it like you do out

of suffocation. When propaganda is disseminated in such

vastly effective ways there is a feeling of, well, somebody's

got to say the other side of all this. You get baited.

The purpose of conservative establishment propaganda is

simply to demoralise the opposition, to gas you into submission.

You fight because you fight for your own mental survival.

That's all it is.

There's a fair amount of political/protest music on

the EPs box, from Peter Gabriel's Biko to The Animals'

Film.

I would like some of my stuff to be more anachronistic

than it is, but sadIy it's not an anachronism to be singing

a song like Te Recuerdo Amanda, written by someone who

was tortured to death by Pinochet's people. And the version

of The Animals' Film is also timely. There's a

central contradiction in the vivisectionists' argument:

they say it helps to experiment on animals because they're

so like us, but at the same time they're saying animals

are so unlike us that they don't suffer like we do. Well,

you can't really have it both ways. There is actually

an organisation called DAARE, Disabled Against Animal

Research - it adds moral clout if disabled people themselves

say that the whole purpose of doing good is to reduce

the amount of suffering in the world.

Have the Rykodisc/Hannibal reissues - including Dondestan

(Revisited), which afforded you the chance to improve

on an album that you thought had been rather hurriedly

mixed - brought a cheer to your heart?

Yeah, it's made me feel like I've been doing something!

I'm really grateful to Ryko. They're a terrific bunch

of people - really friendly and helpful and conscientious.

The way Joe Boyd has done his repackaging of people like

Sandy Denny, who are completely outside the fast traffic

of the commercial record world, keeps these safe little

pockets accessible to anybody who wants to make that effort.

It's also been a chance to refresh things, like Alfie

redoing or adding to the artwork, and also getting some

of the words printed that weren't there before. And really

having another crack at Dondestan, putting it in

more of a context with Alfie's photographs. It's a great

feeling.

But I have been doing other things as well. New recordings

that I've really enjoyed. One was the Federico Garcia

Lorca centenary this year, and this bunch of Spanish people

put together a compilation [De Granada A La Luna]

setting Lorca to music. They sent me a bit of text and

I did it just with a bass player called Chucho Merchan,

who's based in England and played on a couple of tracks

on Shleep - a lovely geezer and a shit-hot musician. They

invited us to Granada for the presentation, even though

I don't do any live gigs, so I was just there in my capacity

as... mascot teddy bear. The other thing was an Italian

group called CSI, who got a bunch of groups to do a CD

of tunes that I've sung [The Different You: Robert

Wyatt E Noi]. Half of them were my songs and the rest

were things I've sung, like Yolanda. So I sang a track

on that, one of their tunes called Del Mundo - the first

time I've ever tried to sing in Italian. It was incredible

to be asked. And the general principle of other people

doing my tunes while I sit at home drinking tea is, I

think, to be encouraged.

Going back to the start of your story, would it be

fair to say that you were blessed with unusually hip parents?

My parents were great. I've only just been orphaned, in

fact: my mother died about a month ago. I've actually

very rarely been directly questioned about what went on

in Kent. I don't remember it being as breezy and glamorous

and easy-going as people describe it. My dad contracted

multiple sclerosis when I was about 10, and my parents

moved out to near Dover. So the backdrop was my dad retiring

early and fading away fairly fast, and my mother struggling

as a freelance journalist to make ends meet. They put

their last money into a falling down old house, and we

were there six or seven years. I went to school a one-hour

bus drive away to Canterbury, and I have to say I was

very unhappy there. And although it's true that I became

interested in music and started playing with other people

who were interested in music, this idea of some swinging

scene is simply not how I remember it. It was grimmer,

and I found Canterbury a rather pofaced sort of town -

I remember going into Canterbury Cathedral and signing

"Jesus Christ" in the visitors' book, and a

school prefect came up behind me and I was caned. I couldn't

keep up with school work at all, so I left when I was

about 16 and spent six years or so floating about.

Floating about where?

It was a rather lonely time. In late teens people might

be going to college or university, whereas I was having

to earn a living. My parents went off to live in Italy,

and then I worked in a forest, and then as a Iife model

at Canterbury Art College.

Then I worked in London, a large kitchen, funnily enough

at the LSE, though I'd only ever see the students through

the hatch. There was a staff of about 80 people there, and

I was about the only bloke and about the only non-Caribbean.

They were such a laugh, and they made me so welcome. I didn't

really know London very well, and they used to take me back

to their places and to their parties. They mothered me around

and sat me in dark rooms with cans of beer, blasting me

with what was I suppose proto-bluebeat music.

Do you generally retain good memories of making music

in the '60s?

I've been quite shocked to see bits of old film where

l'm drumming, and I obviously used to get stuck in on

the old drum kit. But it all collapsed in such an unhappy

way that, to be honest, I don't dwell on it, no. Of course

I worked with some great musicians, but in the end I never

really found a home as a drummer. So that my period of

stimulus and excitement sort of goes from having a really

good time until I was about 10 or 11, until school started

to get hard. Then it's sort of blank, really, 'til about

1971 or 2. What I do remember enjoying was just that little

bit later on: working with people like Henry Cow, that

kind of thing.

I know that your ejection from Soft Machine is something

that's still painful to you. I wondered if the Shleep song

Was A Friend, which Hugh Hopper co-wrote, had any bearing

on that?

So did I!

Alfie: At the end of that song, when Robert sings

"We are forgiven", I wanted to join in and say:

"No! Never!"

RW: Alfie's a tough cookie. The thing is, I don't

really like reading stuff where musicians talk about this

stuff. It all gets so Spinal Tap when you start talking

about "musical differences". How can anybody expect

any number of lads to be able to do their own thing and

stay together that long ? I could have done with some of

the money when we came out of it, but we managed. So we

must all be like Nelson Mandela about these things.

Could Soft Machine have ever been as big as their great

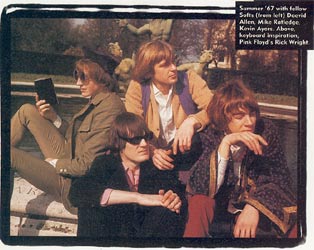

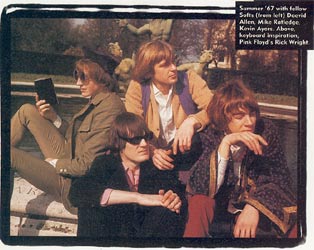

rivals at the time, Pink Floyd?

No, it was too different. Pink Floyd had hit singles from

the start, and terrific ones too. And they had a whole grandeur

and presence that wasn't anything to do with us. The only

thing we had in common was that some of the audiences were

the same in the sense that they were prepared to listen

to tunes they hadn't heard before. I don't think Soft Machine

had enough vision or coherence to get a loyal public. We

didn't really know what we were doing. I was too much of

a jazz fan. I like to travel light, with a little drum kit.

I honestly don't need a lot of the other stuff. I do like

eating fried-egg sandwiches.

Do you still feel a connection to the avant-garde spirit

of that period?

It's an odd thing, that. In fact, there were a lot more

things like what we now call World Music before the beat

group hegemony took over the record shelves, actually. People

did go and see Ravi Shankar, and they did listen to calypso

and bossa nova and all kinds of things. There was a reach

to outside the local culture, a very wide one. Really this

aIl happened in the '50s, and a lot of the stuff was cannibalised

years later in the rock field - by people like us. I wasn't

culturally a rebel at all in terms of my parents. In fact,

I really liked my dad's records and paintings and stuff

that he liked, which was the avant-garde of the first half

of the century. Picasso, Prokofiev. So that was a starting

point, but it was already a nostalgia for an imagined world

that my dad lived in. And even when I got into bebop and

modern jazz in the '50s, it was already nostalgia for an

imaginary Harlem or something. When some people say art's

got to be new, it's got to be cutting-edge, it doesn't mean

anything to me at all. I have no ideology of newness.

|

|

When you played with Jimi Hendrix, did you think, this

guy is light years beyond what most of us are doing?

It was a shock, yeah. It was a lurch. Just how far he'd

got, having not seen the roots of it. Always underestimated,

I think, was his group, and Mitch Mitchell particularly.

There's very few drummers who could have ridden the storm

and clocked where the beat was, what the time was, and dealt

with that funky beat but at the same time flying like the

wind and following Hendrix all over the place. Then again,

Hendrix has to be given credit for such a loose group, far

looser than anyone else at the time. As someone who'd spent

much longer listening to the glorious disintegration of

bebop into Sun Ra and Charlie Haden and Don Cherry, this

felt more comfortable to me than the strict time and neat

and tidy blocks of sound that rock music was locked into.

The music breathed, it had air in it. Of course, bits floated

off and got lost, but that suited me fine. They were a great

encouragement to us, particularly Mitch, who at the end

of the tour gave me his kit. Which I've still got [upstairs].

I've never used another. Everything you hear of me on a

drum kit is on that maple-wood kit.

Also, Hendrix was not a prima donna. He was actually quite

a modest gent, a bit of a grown-up. He' d done those things

that conservatives say young men should do. He'd done his

stint in the forces. So between the forces and Little Richard's

band, he knew all about discipline! He was very, very secure

in that way. But he took risks aIl the time. A great inspiration.

I can't imagine that period without him. He was pure light.

I did see him every night playing something like Red House,

and every night it just made the hairs stand up on the back

of your neck. I feel quite tearful about it, even now.

Do you think if you hadn't had the accident in 1973 that

you would have found the musical voice that you have, and

made the music you've made?

No. One thing I'm really grateful for is not being a drummer

anymore, as a primary thing. That forces me to take charge

of my own music. I should have done it before. It was a

good career move... as everyone said when Elvis Presley

died. I just carried on with what I do, which is basically

slightly out-of-tune nursery rhymes. Up to that point, as

a drummer and arranger, I'd been trying to sort of take

on everything there was to take on, in terms of music-making

- all the harmonic and rhythmic ideas that were available.

Which is a great apprenticeship in music, but then you end

up saying: What actually is your voice? What is it you yourself

have to offer? And the accident made me have to work that

out.

I was thinking about how hymnal many of your songs sound.

The keyboards sometimes suggest an organ in a little country

church, and the voice is like some doleful choirboy. Any

idea where that comes from?

The first things I remember my dad playing, before MS stopped

him, involved us standing round the piano and singing things

like Away In A Manger. I've always liked that rather static

feel. In fact, you get it in surprising places. Some South

African music has it - you can hear the hymns in the background

somewhere or other. Also, some of the most influential music

l've listened to was the Charlie Haden stuff, as arranged

by Carla Bley. Liberation Music Orchestra is stateIy

but ramshackle at the same time. I loved the feel of it.

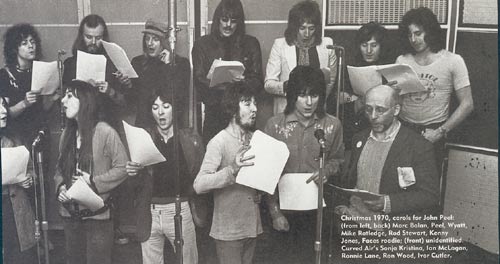

The whole thing came up again in one of John Peel's daft

projects, getting everybody to sing Christmas carols in

the studio. I did Good King Wenceslas with Ronnie Lane -

he was Wenceslas and I was the page, singing in this sort

of falsetto. It came straight out, I had no problems with

it.

|

|

Is it accurate to say your voice

is a countertenor?

I don't know quite what it is. I've lost some top notes

recently, a semitone every year, just about. I can get comfortably

up to about a G above middle C. I've got a falsetto in my

voice that a lot of people use and comes from black music.

I used to listen to a lot of women singers like Dionne Warwick.

I could sing along to Dionne Warwick easier than I could

to Ray Charles.

I've always been curious to know how the sound of Rock

Bottom - that dreamy, murky minimalism - was born in your

head.

Where did the keyboard sound originate?

The keyboard itself suggested it. Alfie got this thing called

a Riviera in Venice, and what I liked about it was that

you were able to slow the vibrato right down - normally

with things like the Hammond organ the vibrato is quite

fast and it's set. So with this Riviera I was able to tune

in with the kind of vibrato I wanted, and I was able to

play rather like I would sing if I could be a little choir.

I could set my voice right into it, and it was like stepping

into a warm bath of sound. I felt really at home. But where

it comes from, I don't know. I was impressed by the way

Rick Wright used to play in the Floyd - it was nothing like

the only way I knew how to play at that time, which was

somewhere between Booker T. and Jimmy Smith. He left all

the drama and dynamics to the other instruments and just

created these glacial harmonic backdrops - a very good bit

of stage-setting, and rather underestimated. So I was affected

by him, although there's a grandeur to what they do, which

is not a word that comes to mind with my tunes!

You sit at this intersection of so many different strands.

There aren't many people who connect Eno to The Monkees,

or Paul Weller to Mike Oldfield. Why is that?

I don't sit down and try and be eclectic. I really like

Paul, and I really like Evan Parker. And me in the middle

is just the same old thing. No, it's just that I really

like all these people and the way they play. Sometimes it's

not to do with their genre, but with the character of the

particular musician. It's the thing I really like about

music and working with other musicians. As a jazz fan, when

you had an Art Blakey, there they were - Horace Silver,

Benny Golson - and you felt these people in the room, you

got a sense of the actual characters. The sense of contrast

between Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, and Miles Davis I

really felt them as people. There's a particular character

trait of someone like Paul that I really find appealing,

and it gives you an extra musical thing. It's the actual

company, the imagined character that comes through the music.

Did you always intend Shleep to be a more collaborative

venture than its predecessors?

Shleep was recorded like Rock Bottom, which is to

say that I was prepared to record the whole thing myself

like Dondestan. So that any musicians coming was

a lovely luxury - a bit of virtuosity, whether it was Annie

Whitehead's trombone or Paul's guitar or Evan's saxophone.

But I'd mapped it all out myself, and wasn't relying on

anybody else to make it work. Their role was to enhance

it. Most of the guests on there would come for a weekend

or something, and they'd work on a couple of songs. They

really brought out stuff that hadn't occurred to me, or

at least had in my head, but I couldn't write the sort of

early Mingusy thing with trombones and saxophones weaving

about, but Annie and Evan concocted much nearer what I had

dreamed of. And I wanted Blues In Bob Minor to be a proper

sort of blues, even though with my rickety rhythm section

thing it's not as beefy as a blues would be done normally.

With a bit of encouragement - he didn't wanna disturb the

mood of the song - Paul took it much further than I had

planned to.

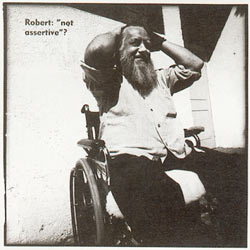

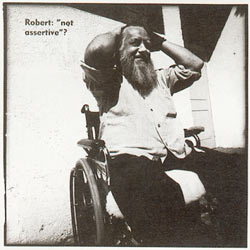

Alfie: Robert's one weakness is that he's not assertive,

so he can easily let things go in order not to hurt somebody's

feelings, or because he doesn't want to be seen as a prima

donna. He knows what it is in his head, but he lets things

go because he doesn't want to mess up the atmosphere.

You've talked often of "rock" as opposed to

"roll". Do you think "rock" as a phenomenon

has burned itself out and become a bit of a joke?

I'd have been quite happy coming out of the '50s into the

'60s if there'd never been any rock at all. l'd have been

quite happy listening to jazz and bossa nova and rhythm

and blues and Cuban music and African stuff. My favourite

guitarist's still Wes Montgomery. I can't think of anything

that was going on that wasn't quite enough for me already.

On the other hand, you'd never have had Hendrix.

That's right. When I actually think of it, there's lots

of lovely rock bands and rock musicians. What happened in

rock music was that the guitar took over the role that brass

sections in rhythm and blues had had. If you listen to The

Contours' original Do You Love Me, it strikes me as being

a stronger, more powerful record than any beat group cover

version: it's got a drama and a clarity and it swings like

fuck. Who could ask for anything more?

Is it an argument, at the end of the day, about power

versus sensuality?

I've got ears, and I can hear how dramatic and exciting

electric guitars can be, but I can live without it. Maybe

l'm not as eclectic as I've been suggesting. A difficulty

I had with rock was that I wasn't altogether happy with

what happened to drumming. I'd been following the history

of drumming in jazz, where rhythm was broken up by drummers

like Kenny CIarke and Philly Joe Jones into this wonderful

breathing thing, and rock'n'roll seemed to me to take it

back to that march-bond thump-on-every-beat, and it just

gave me claustrophobia. It's also a musical thing - a lot

of rock'n'roll is in eighth-note and 16th-note intervals,

whereas what I really love about jazz, and why it's my music

of the century, is the triplet feel of the 12/8 signature,

the implied three and four simultaneously, which you'll

hear in even the most simply equipped West African groups.

That seems to me the organic live element that made jazz

solos possible and gave a kind of flow to the music, and

I'm sticking with that flow... But you could probably stick

a bit of John Bonham on and I'd be going, Yeah!!

|

|

Do you try to keep abreast of pop music?

I don't feel I'm missing anything, but I can't say that

I need much, either. l'm very intrigued by people like Tricky,

and what's going on around his vocals. And a lot of what

happened with dub, those lo-tech ideas of what you can do

in the studio, and then that being picked up by New Yorkers

and them doing pan-tonal stuff with hip hop. Perhaps the

most recent influence I've had was Björk's last record.

I took a bit of courage from her about how to place things.

You have to have no fear of technology. There was a nice

thing she said in an interview: "I'm not scared of

technology, my dad was an electrician!"

Alfie: We really love this record by Wyclef Jean

we've been hearing. Something about November.

Gone 'Til November?

RW: Oh, yes, that's great. As a bit of pop song stuff,

that's the best I've heard since Björk.

You are - are you not? - a godfather of lo-fi. The very

primitive drum machines on East Timor [Old Rottenhat],

for instance.

Absolutely right. And it goes back to when I used to like

Paul Klee's drawings: those spidery pen-and-ink drawings

with splodgy bits on and rather feeble colouring-in. I really

like precarious, rickety things and always have done. I

spent quite a few years in very loud bands, making massive

amounts of noise, and I enjoyed all that. If you're opening

a concert for Hendrix in front of 15,000 Hendrix fans, you

can't piss about. You can't be whimsical, you've got to

come up with something. So I do know about all that.

What was the last occasion on which you performed on

a stage?

It was in a little club, doing Born Again Cretin with The

Raincoats. That would have been about 1983. They did it

very nicely, as it happens.

Could you ever see yourself giving a live performance

again?

I couldn't, no. I dream about it sometimes, and they're

alwoys nightmares: I can't remember the words, the band

doesn't know what key the songs are in, and I've forgotten

what order we're doing them in.

| |

THE CONVERSATION WINDS down

with tea and doughnuts. Outside, a damp, grey sky

unfolds across Lincolnshire. When Robert briefly leaves

the room, Alfie tells me conspiratorially about a

new keyboard a Yamaha "dance keyboard",

she calls it- that he acquired after Shleep.

"I'm always trying to get him to buy something

new," she says. "And he does buy something;

but then of course he can't make any of it work. He's

just not made for machines. He doesn't even know how

to turn them on. He still has the Riviera, but some

of the notes started to break up. The next thing he

was really fond of was this Wasp, a little small computer

thing that made a very good bass sound - he did a

lot of Old Rottenhat with that. There are alI

these sort of dead things upstairs. Like this old

trumpet I got him in a car boot sale."

When Wyatt re-enters the room he plays me the nine-minute

Cancion De Julieta that he contributed to the Lorca

album. It's a huge, mournful thing, with groaning

keyboards and horn sounds like baleful whale noises,

reminiscent of something off Charlie Haden's Liberation

Music Orchestra...

Un mer de sueno

Un mer de tierra blanca...

(Oceans of dreaminess

A sea of white earth...)

"This one was obviously meant for me," Wyatt

says as we listen. "Sometimes I react against

that kind of typecasting, but in this case they were

absolutely right. It's serendipity I think... though

I never quite know what that means. "

Alfie smiles across the table at him.

"I think it's the future, myself," she says.

|

|

|