| |

|

|

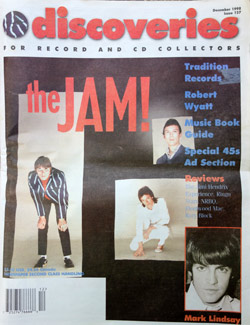

Going Back a Bit - An Alternative History of Robert Wyatt - Discoveries Issue 127 - December 1998 Going Back a Bit - An Alternative History of Robert Wyatt - Discoveries Issue 127 - December 1998

| |

|

|

|

|

"I'm not interested in career moves. I have a puritanical thing about music. You should do what the music wants to be. If that happens to be what a lot of people want to hear, you're lucky, but you shouldn't bend it. I can live off what I do, and even if I couldn't, I wouldn't try and change it. I'd get money some other way.

"

It's a fine philosophy to live by. But then again, it's exactly what you might expect from Robert Wyatt, who's cut his singular furrow in the musical field for more than three decades now. As a member of the (legendary) Wilde Flowers, Soft Machine and Matching Mole he was a vital part of the Canterbury scene that produced so much wonderful music in the late '60s and early 70s. He developed a reputation as a subtle, inventive drummer, and a singer with a marvelously emotive voice.

In 1973 a fall from a third floor window left him paralyzed from the waist down; drumming was no longer an option. He was forced to look closely at himself and at his music, and found that plenty of options were open. In many ways, it was the real start for him, and his records since then have been chronicles of the phases of Robert Wyatt, the man. Of course, they haven't been the limits of his work. Both before and after the accident he's worked with people in a number of fields; the idea of boundaries doesn't seem to come readily to him. Michael Mantler, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Henry Cow, Brian Eno, he's recorded with them all, and along the way he's managed to become something of an icon for musical integrity. In 1987 a young Ben Watt, of Everything But The Girl, recorded an EP with him, recently reissued by Cooking Vinyl on "North Marine Drive." A complete discography would fill pages.

Wyatt isn't the most prolific artist - there was a six year gap between Dondestan and the new Shleep, and five years between Old Rottenhat and Dondestan. But this isn't someone who puts out "product"; this is art, accessible and melodic, but still definitely art, individual and creative.

And 1998 might be the year that finds him a wider audience in the U.S. Shleep has big name guests, people who admire Wyatt and are pleased to help out, people like Eno, Phil Manzanera (Roxy Music), and Paul Weller, the Mod Boy himself. More than that, Thirsty Ear is reissuing his solo records (all but 1970's End Of An Ear) in the U.S., some seeing domestic release for the first time.

This article isn't meant to be a full history of Wyatt: Michael King's book, Wrong Movements, covers that quite admirably.

And, as Wyatt readily admits, "the '60s are something of a blur to me now. I can see photographs of people I knew and not recognize them." Instead it's more a series of linked thoughts, of what helped make him who he is, and his philosophies of music.

Robert Wyatt Ellidge was born January 28,1945, to Honor Wyatt and George Ellidge. In 1955, George Ellidge was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, and the family moved from the London suburb of West Dulwich to the village of Lydden in Kent, some ten miles outside Canterbury. He had a slightly unconventional childhood, with parents whose friends were - for the times - quite bohemian.

"It seemed perfectly normal to me. My father didn't join us until I was six, and he died ten years later, having retired early with multiple sclerosis, so I was brought up a lot by women. My Dad was a psychologist, and my mother a journalist. He was from up North [of England], and she was posh, so I'm a subject of class miscegenation!"

A myth has grown up, making the Wyatt house in Kent something of an offbeat cultural center. Wellington House, as the place was named, was an 18th century building, and the family did take in lodgers, who included Daevid Allen and Kevin Ayers, both of whom would play major parts in Robert's future. But, he says, "I don't really remember musicians coming down to play. I think maybe they did, but when I was no longer there, already on the trot around Europe. We were actually closer to Dover than Canterbury. It was a one hour bus ride into Canterbury. I'd get the bus home at five to my village, so I didn't mix much. It was rather a somber house, really. They supplemented their drop in income by having lodgers, and they were pretty interesting. But most of us, when we could save the money, would go to London for our stimulus. I left school when I was 16 in ignominy, having failed everything in sight, and went off with 20 pounds. I worked in a forest, kitchens, things like that. I remember Canterbury as a rather lonely time, to be honest, and I'm a bit baffled by the subsequent view of it as a kind of country Harlem. I had friends and people did play things, but no more than anywhere else. I was brought up on things that weren't taught in school, like painting, modern classical music, and so on. Nothing at school matched those for interest. I preferred it at home. I lived in my head."

His interest in music would lead him to play in the Wilde Flowers (whose mythical reputation is really undeserved), the band that eventually became Soft Machine, whose other members were originally Mike Ratledge, a Cambridge graduate, on organ and piano, Daevid Allen on guitar, Kevin Ayers, bass and vocals, with Robert behind the drumkit and singing.

This ensemble became a part of the early London hippie scene, along with Pink Floyd Mark 1, and took advantage of Allen's French connections to travel and make a strong mark there. Early sides were produced by Kim Fowley, the man who was everywhere, and in 1968 the Softs toured America as the opening act for the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

"What doesn't come up in these things is the extreme loneliness, even when I was in bands. In retrospect it seems like new, bold things are going on, but my memory is that we didn't know how to do any other things properly and we didn't have a lot in common, so when we formed bands, they were extremely odd. The trouble with bands is that in the end they're all like Spinal Tap. I didn't make sense of how to function until the early 70s."

Soft Machine went through their ups and downs (their first two albums never saw release in the U.K.), moving slowly towards the more experimental jazz that marked Soft Machine 3 (with Wyatt's lovely, and virtually solo "Moon In June") and Fourth. They became the first "rock" band to play at the prestigious Promenade Concerts.

After Fourth Wyatt left the band, envisioning a solo career, but instead formed Matching Mole (a play on words: Machine Moule is French for Soft Machine), who issued two records, then collapsed under the weight of money, or the lack of it.

Then, at the start of June 1973, Wyatt took his fall from the window.

"That's when I found my feet, ironically when I lost the use of them! I could no longer function in a regular group, so I could choose the appropriate musicians for a particular song, or none at all if I felt I could get the mood right myself, and that gave me the freedom to do what I'd done as a teenager with painting, which was take responsibility for what went on. It was so much so, that I felt sheepish about Rock Bottom, (1974) that the musicians had done my thing so conscientiously that on Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard (1975) I gave the other musicians more space, and took a back seat slightly. Sometimes it's nice to let someone else drive, someone you trust. Those two really go together."

1974 and 75 were also the years when Wyatt recorded two singles for his label, Virgin, covers of "I'm A Believer" and "Yesterday Man," the first of which actually made the U.K. charts, and gave people the pleasant surprise of seeing Wyatt on "Top Of The Pops."

"I've had several singles. The reason I recorded pop songs is because I like them, and I'm really interested in them, and it's good to get inside them. I've never written one, but I've got inside them. It was a funny thing. Simon Draper, Richard Branson's ears, wanted me to do singles, and I thought 'Why not? I like pop music.' I had a go of it. He got very excited about it, but I was thrown by the restrictions in the singles market, like the fact that people wouldn't like a Fred Frith violin solo. I thought 'Stuff that!' I'm not going to give people less freedom. I had a lot of fun in the studio, trying to improve Neil Diamond's dull little chord sequence and so on. I don't regret it, but I was baffled, because I thought the whole point of what Branson was doing was to enable people not to be restricted by the pop scene. So I felt a bit pushed, and that's probably why the relationship deteriorated."

After that, it would be the 1980s before Wyatt again issued anything under his own name, pulled out of silence by the independent Rough Trade label. And what he did come up with was Nothing Can Stop Us, largely a collection of work issued on singles, and Old Rottenhat. Both were quite brazenly political albums, and produced Wyatt's other hit single, a luminous cover of Elvis Costello's "Shipbuilding."

"It seemed to come to the surface. I don't think it was deliberate. I work instinctively, whatever feels right at the time, and certain things come to the surface. It surprises me what does and what doesn't. In the '80s I was reacting to what struck me as a fairly barbaric climate. People talk about Reaganomics, but I was talking about the media. When I get down to doing the songs, I'm just doing what comes out. But a lot of thinking and considering goes on before and after. A lot was about how to keep my pecker up in what seemed like an increasingly alien, reptilian world, how to keep your soul warm. There's a certain amount of desperation in that. I'd say, without shame, there's a certain amount of intellectual vigor in that. At times I like thinking deeply and analytically, but they're the times when I'm most uncomfortable, so I have to rethink how I'm functioning. That comes out in the lyrics, and in the music, in a way. There's a kind of tight discipline in the music. When I'm more at ease. It gets looser and sloppier."

The '90s brought a complete about-face with Dondestan, an amorphous, shapeshifting sort of work, impressionistic and often abstract in its moods.

"It's partly a thing I've had about music. Sometimes I wish there was a kind of music that was halfway between silence and music. I think sometimes musicians feel obliged to fill your ears, like a chef who piles up every plate. I'm drawn to the idea of music sometimes not being a great solid substance, but rather gaseous and nebulous, which is translucent, so you can still hear what's going on around you, I've always been drawn to the idea of that. Brian Eno and I had a lot in common in those ideas. He has different references. He's not a political animal in the sense that I am, or a jazzman in the same sense."

And jazz is what's informed all of Wyatt's work, to a greater or lesser degree, whether explicitly - his version of Monk's "Round Midnight" - or in feel, as in the elastic rhythms of "Alifie."

"I don't know; it's the music I listen to. But I don't think the people I listen to would call me one of them. Although I take a lot from jazz, like the shifting harmonic thing, and the rhythmic slipperiness, my tunes are more based on nursery rhymes, folky and primitive. Most jazz musicians would regard me as too unsophisticated to be one of the lads."

Perhaps, perhaps not. He may not be a jazz musician in the conventional sense, but his vision is unique and fully formed as any jazzer's, and people like Keith Tippett, Don "Sugarcane" Harris, Michael Mantler, and Carla Bley don't choose their accomplices lightly.

"I certainly have worked with some great musicians, but I don't read reviews, so I have no idea what anyone thought. And musicians don't say what they think of each other. They say 'D'you want another drink, mate?' 'All right, then.'"

The reviewers, though, have consistently been kind to Robert. He has a sympathetic audience among them, and a cult following around the world, people who've come to his music at different times, for different reasons, and loved it enough to discover the entire canon. As good a place to begin as any is Going Back A Bit: A Little History of Robert Wyatt (Virgin U.K. CDVDM 9031) a double album that spans from the Softs to the '90s (even if the '80s are a bit thread-bare here). From the intensely moving version of "Moon In June" to the finale of "The Internationale" (Wyatt was a member of the Communist Party) it's 29 tracks of delights, some rare, all excellent, with the two 1974 Virgin singles included. And for those elusive '80s, Gramavision put out a CD (79459) that compiled tracks from Nothing Can Stop Us and Old Rottenhat.

The best way, though, is to pick a record - and the new Shleep is as accessible as anything he's done - and dive in. It's music that somehow couldn't be anything but English, with lyrical subjects like insomnia and birdwatching, playful but deep. From there all the others are but a step or two away.

It's not for mass consumption - there probably won't be any more hit singles for Robert Wyatt; the climate where that could happen is a thing of the past. But his music - will be very much his own. And that, after all, is what art is all about.

Chris Nickson

|