| |

|

|

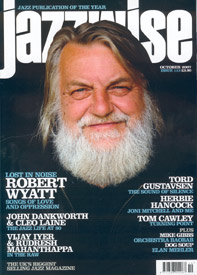

Human

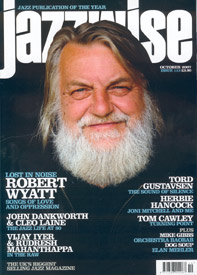

Nature - Jazzwise - Issue 113 - October 2007 Human

Nature - Jazzwise - Issue 113 - October 2007

|

|

H

ow do you describe Robert Wyatt?

Musician? Clearly. Song-writer?

That goes without saying. Activist? Fair enough. But beyond

stating the obvious, it gets increasingly difficult to

define what he does. As if bemused by their own appeal,

his songs defy easy categorisation and yet their charms

communicate across generations and genres. Robert has

just signed with Domino, the hippest of young independent

labels and home of the Arctic Monkeys, Franz Ferdinand

and more oddball talents like Stephen Malkmus and Jim

O’Rourke. Oh, and he’s about to release his

latest album, Comicopera.

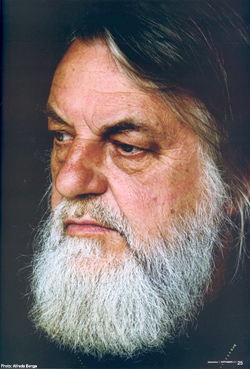

Louth in Lincolnshire, where Robert and partner Alfie

Benge live, is about 200 miles and three decades from

London. Piles of books, records and musical instruments

clutter their rambling Georgian house close to the town’s

centre. Photos, political posters and Alfie’s art

on the walls. In the hall two carrier bags full of paperbacks,

unclear whether they are coming in or going out. Two lives

lived to the full. Outside in Louth itself, Robert and

Alfie seem well-known to the town’s other residents.

In the local hippy shop, all patchouli

oil, josticks and Indian prints, Robert chats with the

owner, pointing me out to her, “This is Duncan, he’s

up from London to do an interview. I just thought I’d

show him your lovely shop.” And in the record shop,

Off The Beaten Tracks, they quickly work out what I’m

doing here, “Yeah, Robert comes in quite a lot, mostly

to order CD’s he’s seen reviewed in Jazzwise."

|

|

The sun is warm over Louth today

and we chat over a sausage bun outside Stan’s on the

market. Robert had been at Ryko for years but a recent take-over

led to sackings of trusted friends, people like Andy Childs

whom they’d known since Robert had been on Rough Trade

records.

If they really cared about the music they’d be pleased

they’d got somebody like Andy. It just didn’t

feel right. So, we left and they were a bit surprised and

a bit cross. But Alfie cleverly got it built into our contract

that we weren’t collateral for deals like that.”

Alfie took on the task of sorting out Robert’s business

affairs some years ago. “This wasn’t by choice,”

she tells me. “This is by seeing how chaotic some things

are and how Robert signs things that are not in his best

interests. Like signing songs to a publisher, who’s

totally hopeless, for eternity instead of checking him out

first."

I turn to Robert, who has a Stan Laurel-like

look on his face: “You should have been a jazz musician,

Robert”. He laughs, “I’ve got the makings,

haven’t I? ‘Jazzwise’ being a contradiction

in terms.” “Yeah, technically and brain-wise,”

Alfie chips in. “I come from a long line of jazz musicians.

Also, there’s been quite a lot of crooks involved in

Robert’s life. It seemed sensible to keep it in the

family but it’s not my chosen metier. I find it really

irritating.”

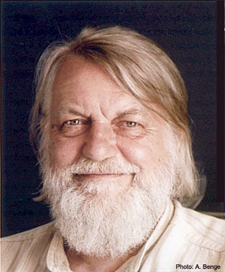

Back at the house, I ask Robert if he minds if I take a

couple of photos. “No, not at all,” he says, “though

I am having a bit of a bad hair life.” I explain that

I’m using two tape machines for the interview, as in

the past machines have stopped working without my realising.

It turns out such things have happened with Wyatt interviews

before.

“The thing that’s confusing for people, if they’ve

had to do it again, is that for every question I have a

completely different answer. So, it’s very hard for

them to sync up an interview. Like, ‘How are the 60s?’

‘Great!’ ‘How are the 60s?’ ‘Crap!’

‘Are you happy?’ ‘Yeah!’ ‘Are you

happy?’ ‘Am I fuck!’ So, that was just a

warning.”

|

|

Robert’s politics, however, remain

more consistent. Like his albums they’re intensely

personal and derive from a strong moral sense. Anti-racist,

due to his love of jazz and black music. Anti-imperialist

and socialist, due both to his parents’ example and

to his own anti-racism. These values are steadfast and infuse

Robert’s songs, not in any crude agit-prop way, but

because they arise naturally from the processes of contemplation

and reflection. Is he glad to see the back of Blair? Obviously.

But does he have any sense that Brown may be any better?

"Actually, I'm grateful that, by association, two of

the most unpleasant Western prime ministers had to go. Tony

Blair dragged them down with him. The whole of Europe breathed

a sigh of relief at getting rid of fucking Berlusconi and

the equally odious Aznar. So, thank you Tony for that. I

don't like doing reverse personality cults. I agree with

Tony Benn about that. But on an emotional level I feel slightly

less ashamed having a grown-up going around talking on behalf

of the British people as opposed to a prep school tosser.

But that's a personal opinion rather than a deeply political

analysis."

Sometimes, it's only the laughing that keeps you from crying,

isn't it? But somehow Robert, and Alfie, stay optimistic.

Of course, the joy, energy and camaraderie that goes into

the creation of a work like Comicopera must surely

help. And the making of a Robert Wyatt album is a painstaking

process. Much of it takes place at home. Though he's used

other people to produce his records in the past, notably

Nick Mason on Rock Bottom and Clive Langer on Shipbuilding,

Robert is essentially his own producer these days. Advice,

however, from Alfie, engineer Jamie Johnson and friends

like Brian Eno and Phil Manzanera also feed in.

"Jamie Johnson is such an intelligent engineer that

we can work as a team when I'm putting stuff together. Then

I get a lot of vocal advice, and 'vocal' advice, from Alfie.

Basically, consisting of, 'You could do that again, only

better.' [chuckles] Actually, Alfie has ideas, like, 'why

don't you try this?' or 'why don't you come in on that set

of notes?' Nick Mason was great because he wasn't a professional

producer. I asked him, partly in gratitude to the Floyd

because they were so nice to us and because I thought that

if anyone knows about sitting in a studio and getting a

good sound out, it's got to be one of this lot and that

turned out to be the case."

Actually, when Robert injured his back in 1973, the Floyd

jumped in and did a couple of benefits at the Rainbow for

him raising over ten grand to help out. They're still friends

and it was in part a suggestion from David Gilmour, that

encouraged greater emphasis on Robert's voice in the mix

on Comicopera.

"Alfie used to get worried that my voice was getting

lost in my own production of it. Also Gilmour said that.

He said, 'People want to hear the voice.' Meaning he wanted

to hear the voice. I thought, 'OK. You can hear it now'.

But I also like it as just something else in there."

|

|

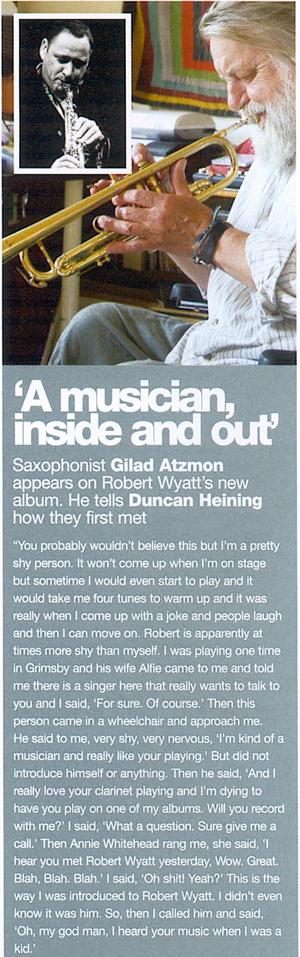

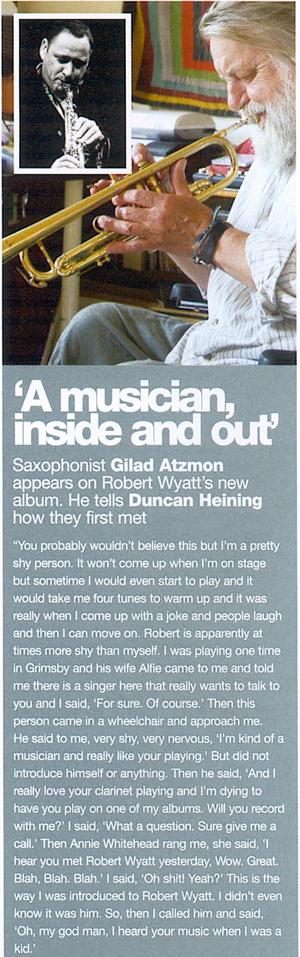

I suspect that the attraction of

Robert's music, for artists as different as David Gilmour,

Brian Eno, Elvis Costello, Paul Weller and Björk,

comes from the fact that there is no separation between

the art and the man. It is that which gives it integrity,

in both senses. As ever, songs off the new album, like the

beautiful 'Out Of The Blue', don't grab the attention even

where their Iyrics are at their most pointed. They sail

into view and touch you even before you're fully aware and

they still have that emergent, improvised quality of his

best work. That, I'm sure, derives from his love of jazz

and is why he chooses such strong players to interact with

on his records. Trombonist, Annie Whitehead is there again,

as are Gilad Atzmon and bassist Yaron Stavi as well as Orphy

Robinson. All three have become crucial to Robert in his

music.

He's known Annie since the 70s, having met through shared

friendships with musicians like Mongezi Feza, Dudu Pukwana

and Keith Tippett. "We actually recorded together the

first time on a record Jerry Dammers put together - Wind

of Change, on behalf of the Namibia liberation movement,

SWAPO. I particularly liked the way she was listening to

what everybody else was doing. She's just utterly lovable,

very, very quick and got an awful Lot of soul."

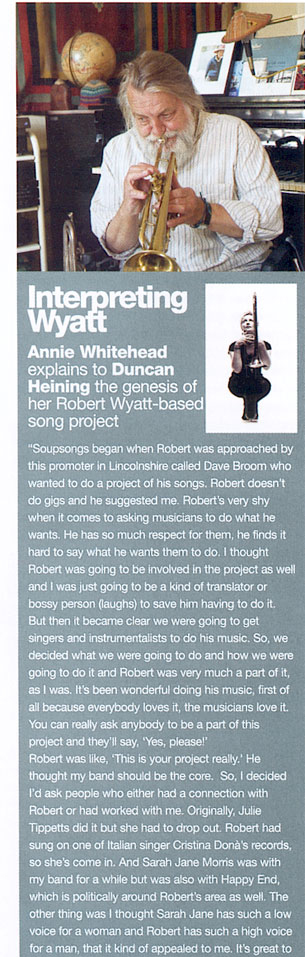

Annie has also put together a group to play Robert's music,

Soupsongs, which has played gigs in the UK and continues

to perform in Europe. As for Gilad, Robert describes himself

as a "sort of Gilad groupie" and he asked the

saxophonist very hesitantly if he'd play on Cuckooland,

his last album for Ryko. "He had no idea who I was

or what I had done or anything like that. I realised he

just loves to play. Whatever I'd asked him to do, if it

involved playing, he'd have said, 'yes'. He was such a joy

to work with. He was just such an enthusiastic collaborator

and so fast at hearing what was required. Yaron Stavi and

Gilad, I regard as like Sancho Panza and Don Quixote and

I love them both. It's very hard to talk about people when

it goes beyond professional admiration to that sort of kind

of love and I have it for various people, Phil Manzanera

and Paul Weller being another two but that's really that."

Singer, Mônica Vasconcelos, is another artist who

appears on Comicopera and is heard to stunning effect on

'Out Of The Blue'. Robert has recently been working on the

singer's new album.

"She got Alfie involved because she wanted to do more

stuff in English and Alfie had a go at some words for tunes

Steve Lodder and Dudley Phillips had written for her. I

did a bit of singing on it and chipped in a few ideas. I

think I was invited. [Long pause) Oh, god, I hope so. I

think Dudley or Steve would...

Anyway that's the forthcoming Mônica Vasconcelos album

and I really like her voice. It's so true. And I use her

on a monicatron towards the end."

That's where Robert records somebody - Brian Eno, Karen

Mantler or, here, Monica - singing all the notes of the

scale. Then Jamie Johnson transfers it to computer and from

there to keyboard, "So I have a keyboard of that person's

voice and I can play chords of it. I love doing that. I

tried it on my own voice but it was rubbish. It was all

out of tune."

As far as singers go, Robert's own tastes are diverse. "I've

been listening to stuff that was very dependant on the idiosyncrasies

of the voice like Johnny Cash and Bob Dylan together. Like

this ultrasmart, ultra-educated Jewish intellectual from

the North and this pure moral, country boy musician and

I find their friendship really moving for some reason. It's

all in there with their record. I thought this is serious

here."

Joni Mitchell is also important to Robert, as is Peter Pears

(Benjamin Britten's partner), mainly because of specific

qualities in their voices. "There's also people in

jazz I like but I can't say they've influenced me. I find

Betty Carter gob-smacking and I like musicians who sing

sometimes in jazz. I like Dizzy Gillespie's 'Oo Bop Sh'

Bam' stuff or Jimmie Smith doing 'Got My Mojo Workin",

which is really kind of rough stuff."

I ask about Chet Baker. There's something in that wispy,

waif-like sound that has parallels with Robert's voice.

"Well, I suppose that's so built in. I mean Chet Baker's

biggest influence on me is the fact that I really like this

thing of a bit of vocal, a bit of trumpet and I think one

of the reasons I took up the trumpet again was because I

was so haunted by that thing of moving backwards and forwards

between those two.

Although I can't play trumpet like a musician, I'm able

to play it like a singer or at least like I sing."

And what about Billie Holiday?

"What I like most about her, it's a bit of a cliché,

but what not to sing. What actually goes naturally with

a voice and in her case if you've got good enough music

around you just let it come through and just ride it like

a yacht. And I really like her later stuff too. Jazz people

say her voice had gone to pieces by then but as far as I'm

concerned that's rock 'n' roll. What did they know? It's

like late period Johnny Cash, it's got 50 much soul."

Robert never set out to be a singer, a fact that still guides

his approach, as he tells me chuckling to himself. "I've

got this completely negative approach to singing - try not

to make too many mistakes, try to hit the right note, be

grateful for that and move discreetly on to the next one."

Early Soft Machine bootlegs, in fact, suggest that Robert

had a pretty fine white soul voice.

"I really got into that classic

English beat group thing which was taking black American

records from Sue and Motown and replacing the backing they

had with a more skiffle-based thing. That's what the English

Beat Group scene really was, Black Music played by skiffle

groups. And I was absolutely part of that and with the Wilde

Flowers live gigs, that's what it was."

At the same time, however, Robert's father and mother were

both great music lovers. The majorily of records they had

were classical, though quite a few of those featured 20th

century composers like Stravinsky, Ravel and Debussy who

were inspired by jazz. It was a remark made by his father,

that prompted Robert to start listening to jazz.

"My dad mentioned he really liked Duke Ellington and

Fats Waller because he'd seen this seminally important film

Stormy Weather, that celebrated black culture albeit in

that sort of ersatz way. So, I got Duke's Such Sweet

Thunder when I was 11 or 12, which he sort of approved

of because it was a Shakespearean Suite, and I was off.

I was just completely, as they say, blown away."

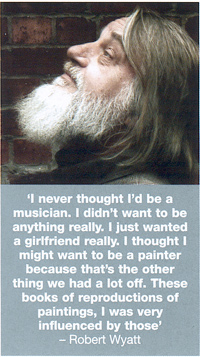

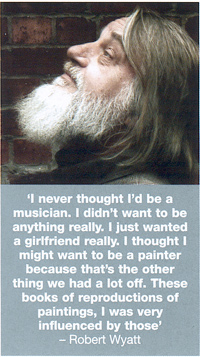

The other thing that Robert mentions as being important

was his parents collections of art books. "I never

thought I'd be a musician. I didn't want to be anything

really. I just wanted a girlfriend really. I thought I might

want to be a painter because that's the other thing we had

a lot off. These books of reproductions of paintings, I

was very influenced by those." It's there perhaps in

the painterly attention Robert brings to his work but also

in the collage-like impression his songs leave. It's entirely

fitting that Alfie, herself an ex-student of art and film,

brings those same skills to the covers and typography of

a Wyatt record. "We are absolutely a team, me and Alfie.

She has all these skills she acquired from art school and

because she gets involved sometimes with the music and the

lyrics and we do so much together, she's naturally part

of everything I do. She's the one who really took control

of how things are done, like cover art and presentation

and typography.

Ever since Rock Bottom, she's been in charge of that. She's

particularly conscious that now people can download, the

whole thing should be worth having as an object.

The drums were obviously an early enthusiasm and Robert's

first drum kit consisted of the usual mix of household objects,

which he'd use to play along with Max Roach "Bit ambitious

that'. His first proper kit, the cheapest Premier set he

could buy, lasted him through his early professional career.

He had lessons with a visiting American drummer and summers

were spent on Mallorca living near Robert Graves, a friend

of both Robert's parents. Graves' son-in-law owned the Indigo

Jazz Club and Robert got to practise and even jam at the

club. His first group with Kevin Ayers, Hugh and Brian Hopper

and Richard Sinclair was The Wilde Flowers and when that

disintegrated, Robert formed Soft Machine with Ayers and

Mike Ratledge. Sharing the same management as the Jimi Hendrix

Experience, the group toured the States with Hendrix. The

downside of that was that Robert began to develop a big

liking for alcohol and it was whilst under the influence

that Robert fell from a window in June 1973 and ended up

paralysed from the waist down. The upside, however, was

that he learned a great deal personally and musically from

playing America, not least from Hendrix's drummer, the sadly

underrated Mitch Mitchell.

"Going from Beat group gigs to bigger gigs, Mitch really

taught me a lot about how to handle that musically. In fact,

he gave me his kit when the tour ended because he said,

'Robert, I can't bear the thought of you playing on that

crap kit you've been playing'." Robert laughs his body

quivering at the memory. He still has the kit. Both he and

Mitchell shared an enthusiasm for jazz drummers, Elvin Jones

and Tony Williams. "Me and Mitch used to listen to

a particular track by Miles Davis with Tony on it, 'Stuff',

but I've liked Tony Williams ever since he was with Jackie

McLean. Elvin, we loved because the momentum and the weight

of what he did was very useful information because of the

volume at which rock groups played. He actually matched

that sort of depth and volume of rock."

Inevitably, the shock of hearing Hendrix for the first time

has stayed with Robert. "I still remember first hearing

Hendrix get into gear in rehearsal. You just thought, 'What

the fuck is that?' This sensaround thing of controlled feedback.

There were people like Jeff Beck and to a certain extent

Pete Townshend who were controlling feedback but this sustained

landscape at a certain volume and absolutely controlling.

It was blinding. It was like a great living, breathing river

of sound."

There was opposition in some quarters to the Softs doing

the tour but Hendrix supported them. "Some people thought,

'Soft Machine? They're not very poppy. He's playing stadiums.

He's got hit records.' But I'm very grateful to Hendrix

because he stuck up for us, and the band did, and Hendrix

didn't like pop groups that much. He wanted people who were

trying something different and didn't want people copying

him. And, of course, we weren't. We were trying to do something

else. He was very respectful about what we were trying to

do and (laughing) very polite about our ability to do it.

Real gent."

Though he's put in the occasional guest stage appearance

with friends from Annie Whitehead to David Gilmour, Robert

stopped doing gigs not long alter his accident. People would

love to see him live, as he knows. "I feel a bit sheepish

about it because normally the gigs are the promotion for

the LP. The difficulty with gigs is that I don't really

think like that. So much of what I do now depends on a kind

of Beach Boys-isation of the voice, of double octaves and

so on. It's all in the editing. I tried to do a sort of

imitation of a live gig with Annie's band. A couple of songs

came out all right. But I wasn't really comfortable and

some of them were so not right and there was nothing I could

do about it. I just don't have that kind of confidence to

do it live in front of a band. I did drumming and drunk

but voice and sober, it's just not going to happen. I don't

have that chutzpah."

Maybe Domino and Robert's many friends might someday persuade

him. It would be wonderful to see him do a short residency

at somewhere like Ronnie's. Somewhere he'd be appreciated

but also somewhere intimate, where the warmth of the man

could come across. Till then, there's Comicopera

and Robert's back catalogue to keep us happy. |