| |

|

|

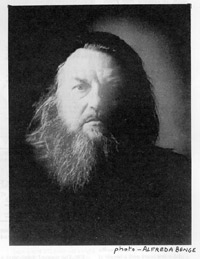

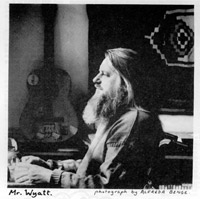

Robert

Wyatt - Ptolemaic Terrascope Vol. 3 - N°1 - January

1992 Robert

Wyatt - Ptolemaic Terrascope Vol. 3 - N°1 - January

1992

ROBERT WYATT

| |

|

|

The "Canterbury Scene" are three words which have

become common coinage in these pages in recent times;

not because of some strange fannish addiction to

anything emanating to that region of England, but

simply due to the sheer quality of the music which

has umbrella'd out over the years since those humble

'Wilde Flowers' beginnings of 1964. Whilst musically

unimportant in itself, the Wilde Flowers contained

in its original line-up three people who, within

a decade, were to be considered in many circles,

the definitive English rock vocalists: Richard Sinclair,

Kevin Ayers, and of course Robert Wyatt.

Whilst always highly rated as a drummer, it is for

his wonderful singing and songwriting that Wyatt

is today universally admired and respected. The

lack of his vocals in the Soft Machine after the

glorious 'Moon In June' on their album 'Third' (unbelievably,

he only drums on the following album, 'Four', as

the rest of the band believed his voice to be dispensible!)

marked the departure of any real interest in the

band; however in the subsequent Matching Mole, not

only is there the treat of hearing Robert's voice

combined with the equally unique sound of Dave Sinclair's

keyboards, but there's also what many people consider

to be one of Wyatt's finest moments - the near perfect

love song 'O Caroline', a desert-island-disc if

ever there was one.

As is Wyatt's second solo album, 'Rock Bottom' -

a masterpiece of languid depths and charged emotion.

The previous LP, 'End Of An Ear' is for avant-gardeners

only, while the third LP, 'Ruth Is Stranger Than

Richard' is more free blowing but none the less

essential. Together, this pair of platters confirm

for all time the talents of Robert Wyatt and his

place in the hearts and minds of his listeners.

Since then he has sporadically put out a handful

of excellent singles and the occasional LP on Rough

Trade as well as making several guest appearances,

most notably on Nick Mason's LP 'The Fictitious

Sports' alongside jazz keyboardist Carla Bley.

Now that the Canterbury scene is again up and running

with Caravan, Going Going (featuring Hugh Hopper)

and Richard Sinclair's Caravan of Dreams, as well

as rumours of an upcoming and long overdue return

to form for Kevin Ayers and a strong new album from

Robert Wyatt entitled 'Dondestan' on Rough Trade,

it seems only right and proper that the Terrascope

should be in the thick of it. Hence the following

interview.

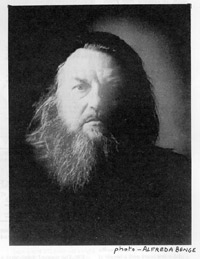

Whilst Robert, as you will see, was until recently

unaware that he was considered an integral part

of the 'Canterbury Scene', there is no denying that

he has always been considered as such and his response

is in terms of a mistaken geographical and biographical

reference rather than in the general use of the

term 'Canterbury' as a broad but distinct musical

genre - one which rightly labels the likes of Dave

Stewart and Jimmy Hastings as 'Canterbury', even

thought neither of them has ever lived there. That

small point cleared up, it's on to the results of

a delightfully jovial afternoon spent in the relaxed

and friendly company of Mr. Wyatt, an afternoon

in which, fuelled by impromptu notes, failing memories,

quite a lot of tea and the occasional (and vaguely

apt) banana, we touched on as many aspects as possible

of his long and never less than interesting career...

|

|

|

|

PT : How did it all begin?

RW : It's a long story. When the Romans left Britain...

oh, then a few other things happened, I was born in 1945,

went to school in the Fifties and left at the end of them.

I think the Fifties were a very good time to be at school.

It was in Canterbury - people say 'Oh, Canterbury', but

I went to school there and that's all there is to it.

PT : You didn't live there then?

RW : No I didn't, I lived near Dover actually,

although I did have a spell there in late 1960 or early

'61. I couldn't make head nor tail of school, I had a

coupIe of friends there - one of whom from the age of

about 10 was Hugh Hopper. His older brother played clarinet

and had some nice records. My big brother had some nice

records as well. But because our records were our big

brothers' jazz record collections, people think we had

older tastes than others our age.

PT : You obviously heard the radio as well, though?

RW : Not obviously at all. I never heard the thing

much, quite frankly. We preferred records: jazz, some

R&B - we were fans, as teenagers are. Then Hugh got a

bass guitar and started playing some Ray Charles type

stuff, so there was this twin-tracked thing going on,

some dance or song-based music like R&B and some harmonic

and melodic deviations of the modern jazz of the time.

What we played was neither one or the other in the end,

we sort of fell between two stools and stayed there, on

the floor.

PT : Great play has been made down the years of the

fact that you had various musical contemporaries at school,

but in fact they weren't exactly contemporaries at all

- there was a year or so between you all?

RW : That's right. I vaguely remember Dave Sinclair

playing piano for the school hymns, but I knew his older

brother better because we studied violin together for

a couple of years. I think the myth really is more glowing

than the reality. School life for me consisted mostly

of trying to catch the same bus as the girls in the other

schools. And I'm very glad I did, because my first wife,

Pam, was a girl who lived on the same bus route. She kept

me for years afterwards, working as a secretary for some

fairly unpleasant cleric when I didn't have two pennies

to rub together. I did a few jobs after leaving school,

worked in a forest near Folkestone for instance, but that

was it. We had a son - he's in his twenties now and a

nurse - but that's really the most positive thing I can

remember coming out of school. There was some music though,

of course. Daevid Allen, who's a nomadic Australian, had

come to Europe and floated about London and had some contacts

which later became invaluable - people like Hoppy, who

set up various gigs. I've come to the conclusion that

the whole world is gradually becoming Australian... anyway,

there was this bunch of people who were fairly radical

in their own fields. And Daevid was older than us, so

he showed us around. He used to get stoned, so he was

my introduction to all that. He also had a dog which he

used to take for walks with him - it was actually a tin

can on the end of a bit of string which he would trail

some yards behind him. To an impressionable lad of my

age, that was pretty far out!

PT : And your first group, The Wilde Flowers, came

together then?

RW : Hugh was the one in Canterbury who wanted

to get a group together. We (the Wilde Flowers) did basicalIy

R&B covers rather than hits, although we did occasionally

do Beatles songs and stuff. The point is though, Hugh

started writing his own material at this time and I would

do odd bits as well - I started singing for instance,

because he wouldn't sing himself. It was all a learning

process, realIy. [Referring to Richard Sinclair's comments

in issue 8 of the Terrascope:] Mine and Richard's memories

of Wildflowers material seem slightly out of synch - the

soul material I remember doing was like James Brown, Nina

Simone, and simple jazz pieces like Watermelon Man (Herbie

Hancock). But of course other stuff like by rock &

rollers such as Chuck Berry was often thought of as Brit-beat

music at the time...

PT : You did some demos as the

Wilde Flowers, didn't you?

RW : Somebody knew a popular Radio Two styled musician

named Wout Steinhaus who played steel guitar, he had a studio

and let us make some things in there. I imagine they were

pretty appalling.

PT : They included a version of 'Memories', I think.

(Robert later recorded it as the B-side to 'I'm A Believer')

RW : It's possible, yes. Hugh wrote 'Memories' quite

early on I can remember singing that. That was the challenge,

really trying to play stuff that people hadn't heard before

at local dances. Most of the time it was... it didn't have

to be hits, but things that were on the band circuit at

the time. I think after I left the Wilde Flowers went on

to play that stuff very well, but by then I had drifted

off with others, making odd noises here and there. The amoeba

sort of split one half of the Wilde Flowers eventually became

Caravan, and the rest became that other lot.

|

"One

half of the Wilde Flowers eventually became

Caravan, and the rest became that other

lot."

|

|

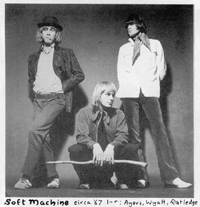

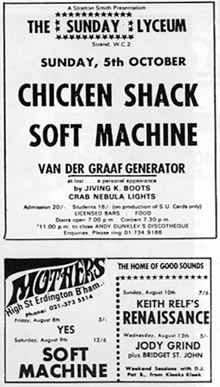

PT : I've got the original line-up of the Soft Machine

down as yourself, Kevin Ayers, Daevid Allen and Mike Ratledge,

plus the guitarist Larry Nolan who left after a few gigs.

Some demos were done with Georgio Gomelsky. Why did Daevid

Allen leave fairly early on?

[as an aside, the demos are now out as 'Jet Propelled Photographs'.

In 1972, Daevid Allen said of them, 'They're just a mortal

embarrasment to me because it's probably the worst guitar

I've ever played... but Robert is just magnificent so their

release is justified'. The band also did the 'Feelin', Reelin',

Squeelin" single - produced by Kim Fowley!]

RW : We played some music for a play by Alfred Jarry

at the Edinburgh Fringe, I think it was. As a result of

that we met people on the avant-garde circuit ('avant garde

a clue', as Ronnie Scott calls it) who had connections in

Paris, where there were student rebellions going on, people

trying to set up autonomous universities and stuff. There

was this bunch of people doing a play by Picasso called

'Desire Caught By The Tail' in the South of France, for

which they wanted a band to play some suitably anarchic

music. We went to do that and did some gigs alongside it

in the same area. It turned out that a lot of Parisiens

were down there, and some New York dropouts like Taylor

Meade, so we got known amongst them. Anyway, when we came

back, Daevid's Australian visa had run out and they wouldn't

let him back into England. He stayed in France and went

on to do stuff like Camembert Electrique etc. It was as

simple as that.

PT : Then came the American tour with Hendrix and Eire

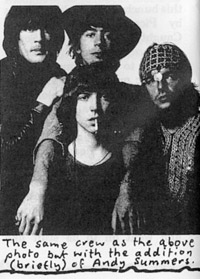

Apparent? [with new member Andy Somers - later of Police

- on guitar . He left after a few gigs to join Eric Burdon

& The New Animals]

RW : Yeah, we got a deal with

Anim-management, the Animals people, and because they'd

also signed up Jimi Hendrix, we all went on the road to

the States. What was useful about that was, a tour like

that soon knocks the whimsy out of you. Playing in front

of a few thousand beer-soaked Texan teenagers waiting

impatiently for Jimi Hendrix does something for your nervous

system. It makes you get on with things and state your

case. It could have been awful, it could have been very

frightening for us - we were going around there with very

little money with bands who were using a lot of money

(although it turns out they weren't getting to see a lot

of it) - but luckily, the Jimi Hendrix Experience were

very protective towards us. Like, Hendrix would sometimes

get some flak for having this weird-sounding band at the

beginning of his show, and he always said look, they're

trying to do something, they're not trying to copy anybody

else, and I want them on the show, OK? He personally stood

up for us, even though we were making a lot of musical

mistakes and hadn't got it fully together. The others

in the Experience were simply terrific as well, and they

were always doing things for us without seeming to use

their privilege. Like, Noel would say look, we're all

going down to this club and we want to go in mob-handed,

so you'll have to come too. What he meant was, we know

you couldn't afford to go in, we know you couldn't afford

to buy any drinks once you're in there, so we're taking

you. But they'd never put it like that. Mitch helped us

a lot as well- such a brilliant drummer, he'd been with

Georgie Fame before, and you have to be good to work with

somebody like that. A very proud bloke, quick to take

offence but he's actually all heart. Sitting there watching

them play every night and seeing how they'd work was great

for us. Mitch had had this maplewood drum kit made to

his own specifications, and at the end of the tour he

gave it to me. Everything I've played since as a drummer

has been on that kit which Mitch gave to me.

PT : So you have some good memories

of that tour?

RW : Absolutely, yes. I mean, I know 1968 wasn't

an easy time to be in America, I saw a lot of horrible

things which make you think a bit. You read articles here

sometimes about racism and of course we have a right to

talk about it, but unless you've spent some time in the

States where the streets smell of racism, you really have

no idea. I saw the kinds of things that a sheltered English

lad had never seen, the hostility between the police and

any kids with hair... the police would ride through crowds

on motorcycles without even waiting for them to clear.

I saw them pick up one kid, hold him horizontally and

run him into a wall like a battering ram. We were pretty

much sheltered as a group going from hotel to hotel, but

you could see that life on the streets was sticky.

PT : Did Hendrix himself suffer from the racism at

all?

RW : Well, Hendrix was a rich entertainer, therefore

he couldn't really be black. It was a class thing. You'd

get cops standing at the side of the shows saying 'hey!

That nigger picks good!'. But there's always been a place

in America for the black entertainer. Mind you, they've

a reason to be grateful. I mean, where would American

music be today without the black American's contribution?

About as famous as New Zealand's I should think.

PT : The Eire Apparent album (on Buddah) came out of

that tour - are you on it?

|

"Hendrix

was trying to turn it from pop into something

more dangerous..."

|

|

RW : Yeah, that was nice. Me and Noel did girly

choruses basically, and Hendrix was trying to turn it from

being pop into something more dangerous, as he saw it.

Eire Apparent were a very nice bunch of Irish lads. They

joined us for the second half of the tour, in a way it

was to get something more poppy in on the act - but they'd

been signed up and we reorganised the concerts accordingly.

It was a good, contrasting sort of thing. I have to say

though that even on our best nights, Hendrix would simply

erase the memory of everything that had gone before. He

was just so fucking good. And consistently good, too.

Better than on the records, actually - that's one thing

we had in common, I think we played better than we ever

recorded and I think he did as well. That's the jazz element

for you.

PT : The first Soft Machine album was actually recorded

in New York?

RW : That's right. Now, what was the name of the

guy that produced that?

PT : Tom Wilson?

RW : That's him. He'd worked with Frank Zappa so

they figured he'd be able to deal with us. He was very

nonchalent, not kind of fretting - just play, we'll tape

it and it'll come out alright. It's easy. He was living

his life, and we were welcome to join in if we wanted

to. But he made sure all the nuts and bolts were all tight

- he did his job. I have to say though that because we

in the group never got on very well personally, in a studio

situation you'd be dealing with each other much more whereas

on stage, you're all facing the same way which is outwards

- so somehow we could work together much better live than

in the studio.

PT : When was the last time you listened to that album?

|

"I'd

no more listen to that [first Sort Machine

album] again than I would put my school

trousers back on"

|

|

RW : About twenty years ago. I'd

no more listen to that again than I would get out my school

trousers and put them back on. I accept it completely,

but the only way I can concentrate on doing my best is

by clearing whatever's gone before ruthlessly away. I

couldn't function by sitting in my own bath water!

PT : The Sort Machine disintegrated at that point -

you stayed in New York and then later moved to Los Angeles?

RW : Yeah, I liked New York. Mitch took us around

and introduced us to some other musicians that I might

not have otherwise met - people like Larry Coryell. Then

Hendrix booked a house in Los Angeles at the end of the

tour, a big L-shaped place it was - basically they're

only stage sets for Perry Mason films, but when there's

no Perry Mason going on, people live in them. So there

we were in this L-shaped stage set with people shouting

'hi!' across the swimming pool...

PT : You recorded some demos while you were in New

York and LA?

RW : I did, yeah. Jeff Dexter's just found one

of them, I must have left it at his house by accident

- but it's only an acetate so it gets really grunged up

whenever you try to play it. It costs a lot of money to

re-record them and clean them up, but he's trying to organise

that at the moment. I also started writing bits and pieces

which turned up in later reincarnations of the group.

PT : At that time, did you consider

yourself to be a part of Soft Machine?

RW : I don't know what I felt, really. I remember

thinking that I wasn't being a very good father. Anyway,

we came back to England and found people were wanting

us to do some gigs, so we 'phoned each other up to see

if we were all into it. Kevin Ayers wanted to do his own

thing, so Hugh, who had already been roadying for us and

had actually written some of the best tunes in our repertoire,

was the natural choice for a replacement. We reformed

really as a response to being offered jobs. I thought

God, this noise we're making is boring. I went down to

the Marquee and saw Keith Tippett's band and thought they

were really good, so we asked if we could borrow their

brass section for a while, which made it a bit richer.

We went on the road like that for a bit.

PT : You'd already recorded the second Soft Machine

album by this time?

RW : I think so - I can't really remember. I haven't

got a copy of that one, either.

PT : And by the 3rd album, by which time sax player

Elton Dean had joined, the band seemed to have fractured

- it's like a side each, really?

RW : I suppose so, although I must say I enjoy

Hugh's side, the live side. There was this British jazz-rock

thing developing though and I found it a rather tight-arsed

thing really, a fairly weak version of what was a pretty

dodgy idiom in the first place. I thought, I'm literally

not going to get a word in edgeways here. I got all my

fun from doing gigs outside of it, playing with Keith

Tippett's friends or with the South African exiles that

were around. It might not leave any great records, but

it was nice to be working with people you enjoy being

with. The adventure of trying things out seemed to be

more important than getting polished results and showing

off tricky time signatures. The corsets seemed to be tightening

by the month.

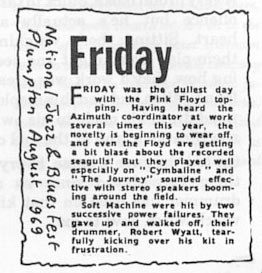

PT : The Soft Machine's appearance at the Proms happened

about this time, didn't it? (13/8/70)

RW : Yeah, we were invited there by a very nice

English composer named Tim Souster who, being an English

composer, had a night to himself at the Proms. He'd written

a piece for it which didn't last the whole night, so he

thought 'I'll get that band in, that'll stir it up...'.

I didn't really like playing there (the Royal Albert Hall)

because I couldn't hear what we were doing - it's an appalling

place to play. My microphone wasn't on when I was singing

and the organ kept breaking down. We did get to be interviewed

by Richard Baker though!

PT : Next we had your first solo album, 'End Of An

Ear'?

RW : Yeah, that was me throwing off the corsets

basically. All hell was let loose. I just screamed me

head off and had a lovely time, I even played the piano.

I can't actually play the piano, but I thought right -

l'm going to play the fucking piano. Turned out I could

play what I wanted to hear after all. Just goes to show,

you never know until you try!

PT : And you recorded 'Bananamoon' with Daevid Allen....

RW : Did I? You're right, I think I did.

PT : .... and went on the road with Kevin Ayers and

The Whole World.

RW : That's true. I remember, he'd take two rooms at the

hotel - one for him and one for the rest of the band.

I mean, I know it was Ayers' band, but I'd never heard

of that before! I come from this sort of lefty, co-operative

background so I wasn't used to this sort of colonial treatment.

Me and Mike Oldfield, Dave Bedford, LoI Coxhill alI scrunged

up in this little rat-infested room - well, I suppose

we were the rats really. Anyway, I thought that was a

bit off so I jumped out of the frying pan and went back

into the fire for a bit.

PT : To do the 4th Soft Machine album.

RW : That's it. Back into the fire, as I say.

PT : And then onto Matching Mole with David Sinclair,

who was later replaced by Dave MacRae, Phil Miller and

Bill MacCormick?

|

|

RW : Well, I wanted to play

with people I got on with, who would let me sing. Jazz and

rock was turning into a horrible hybrid form like railway

lines that you couldn't get off. I wanted something that

was using that same eclectic approach but which was looser.

I liked bands like Tony Williams' Lifetime, a real joyful

sort of traffic jam of a sound - like a conversation rather

than a series of solos. We did a few tours and a coupIe

of albums and just muddled along for a lot less money than

I was getting before, but I'm a bit suicidal like that.

I left the previous band just as they were starting to break

even as well. I think Matching Mole would have carried on,

but at the end of it Dave McRae [the man who wrote all the

'Goodies' songs with Bill Oddie!] wanted a trio which concentrated

on me on drums and I didn't want to be corralled into that

again. We did do some gigs as a trio, me and Dave and a

bass player, and I really enjoyed those but I wanted to

start singing properly. I also met people who hadn't been

into the jazz thing at all, like Francis Monkman, who was

into working out composed structures. I was working on both

of those things really when I broke my back, so obviously

that put paid to them both because I couldn't drum any more,

and I didn't really feel like singing either. I spent most

of 1974 - or was it '73? I can't really remember when I

did it - in hospital. People think that the LP which came

out afterwards, 'Rock Bottom' , was about being paraplegic

or about breaking your back - but it's not. I don't write

songs about being paraplegic, l'm not that introspective

actually. I'd already written quite a lot of it beforehand,

it would have been material for the group with Francis Monkman.

PT : That group [Matching Mole Mark 3] never happened

though?

RW : The reason I didn't want a group was that it

was totally unfair, for a start asking musicians to hang

around for months while you're sitting in hospital even

though, nice geezers as they are, they might have done so.

It's just not fair on them, I mean they've got to earn a

living. And then wheelchairs - you just can't get them anywhere.

It's taken my wife six months to find this place we're sitting

in now, a single flat in London that a disabled person can

use and afford. Touring would be quite out of the question.

It would be hampering a whole group of people if I formed

a band, it's completely out of the question. So the best

thing was that I get my material out, such as I had, and

try to do as much of it as I could myself. I got together

with Nick Mason, a friend from the late Sixties, and he

helped co-ordinate stuff that I couldn't possibly arrange

myself - and we just got other musicians in to flesh it

out. They seemed to understand my stuff- to me, the Rock

Bottom group was more like a group than anything l've ever

had before. We knew each other well enough to be able to

work together, but the situation was unusual enough to put

an adventurous thread through it and make everybody stir

the creative juices a bit. I felt better after that than

I had done for years.

PT : You obviously had some understanding people around

you then?

RW : I certainly did. I got remarried - in fact,

I think our wedding day was the same day as 'Rock Bottom'

came out. It all came together nicely. My first wife and

I had split up quite amicably, but as I say I just hadn't

been a very good husband or father. I was just too busy

speeding about all over the place. So maybe it was a punishment

or something...

PT : But then, with respect, you weren't able to speed

about so much, were you?

RW : Well, no. That's what my wife says, too!

PT : And then you had your hit single, 'I'm A Believer'.

RW : It was more of a single than a hit, but you

can put the two words together if you want to. It was Simon

Draper, the A&R man at Virgin,'s idea. Especially in

England, record companies get very worried if you don't

do singles.

PT : And you did a concert, as well.

RW : Yeah, Dave Stewart came along, Mike Oldfield

- he was brilliant, he heard all my keyboard stuff, which

I thought was inimitable, and just did it. I thought well,

that puts me in my place, doesn't it? It was a good laugh,

except Virgin sneakily recorded it and then put the cost

of recording onto my bill, which I thought was a bit nasty.

PT : Next, you did the second album - 'Ruth Is Stranger

Than Richard'.

RW : That's right. Although it had my name on it,

it was basically a lot of people doing things that they

hadn't perhaps got another context for. I did a duet with

Fred Frith on piano - Fred's got this wonderful lyrical

side to his music which he likes to play down, but it's

a shame to waste it. I just stuck some words on, and copped

half the royalties for that which I thought was a bit unfair

really. Brian Eno came along and mucked about with it all.

He didn't like jazz, so it was good having him in on it

- like a bit of salt where it might have been all sugar.

He was good company, he's a witty man. They (Virgin) charged

us an awful lot for recording it at the Manor - I think

I only stopped paying it off two years ago. I don't think

we're supposed to live this long, really. It's not in the

contract!

| |

"I

don't think we're supposed to live this long..."

|

|

PT : You were doing live stuff with Hatfield And The

North as well?

RW : D'you know, I'd completely forgotten about that.

Yes, I did do some stuff. And I'm on one of the tunes on

their album ['Calyx']. I later wrote some words for it,

but we never recorded that.

PT : Anyway, we had the two albums - what about 'Yesterday's

Man' - wasn't that supposed to be a single?

RW : Well, yes - but Virgin Records felt it was a

bit...lugubrious. I liked it, myself. It only ever came

out on a compilation.

PT : So how much do you feel part of what we loosely

term "The Canterbury Scene"?

RW : I didn't even know it meant me until interviewers

started asking me about it. As I say, because I'd bussed

in from outside to go to school there I didn't really consider

myself a Canterbury person. I think it really means people

like Hugh Hopper and Richard Sinclair, who are genuinely

based in that area. I met them there and I'm eternally grateful

that I met someone like Hugh who provided something I don't

think anyone else could have provided. My mind doesn't dwell

on it as a place though, if I recall a former fantasy world

upon which I draw, it's Harlem in the Forties and not Canterbury

in the Fifties.

PT : Then there was a bit of a gap in your career?

RW : Well, what looks like a gap was just me living

and not putting things down for posterity. I spent a lot

of time sitting and thinking, worked on some odd things

including a play by Harold Pinter. By that time I'd become

more interested in what's now called 'World Music' - basically

it's just anything that's not done by young white men from

England or America. Or Australia, yes indeed.

PT: Then we had the string of singles on Rough Trade?

RW : I was going to a lot of political gatherings.

People would ask me who I thought the best vocalist I'd

heard that year was, and I'd say Dennis Skinner. His gigs

were a lot better than most rock gigs! Alfie (my wife) took

very good care of me, was always devising things for me

to do to prevent me from getting bored like going to a festival

of foreign films, that was a real eye-opener. Either because

of that or in spite of it, I started to get more and more

impatient with the idea that rock music is intrinically

rebellious. Compared to the marginalised lives that the

people I was becoming interested in were leading, the rock

thing was a very safe and cosy part of the establishment.

The establishment has always had a place for rebellion.

Rock and Roll didn't invent that. So then I met a woman

named Vivienne Goldman who was writing at the time about

reggae from a political point of view. It was a very enlightened

look at why black kids in London were being more un-English

than their parents. She introduced me to a friend of hers,

Geoff Travis, who was a&r man for Rough Trade Records.

Geoff said, if ever you feel like recording again, let us

know. I hadn't got any albums in my mind, but I thought

I could at least try some of these other songs that I'd

been listening to. So I deliberately went out to do a Chilean

song or a Cuban song or get some Bengalis in the studio

to play something. That generated my juices again, and it's

that which really got me back into it.

PT : So you did several singles...

RW : Well, I didn't figure I was ready for an album,

and besides they weren't supposed to be something that would

last. They were done quickly, and there was that feeling

about the punk movement which I've always liked, the same

as with Matching Mole, that it wasn't a question of a polished,

finished product, it was just the adventure of trying things.

PT : I suppose the most successful one was 'Shipbuilding'?

RW : Yes, eventually. I think what happened was,

Clive Langer and Elvis Costello had heard a few of my singles

and cottoned onto them, I think Costello liked the way I'd

done a choir-boy version of a chic disco thing ['At Last

I'm Free']. So they wrote 'Shipbuilding' and offered it

to us to do - said they considered it a Robert Wyatt song.

I was really impressed that they could do that, imagine

what somebody else would do and find it just fits them like

a glove. So Costello took us into the studio and produced

it. Basically I just sang over a backing track. The bass

player from Madness [Mark Bedford] played on it. Mind you,

it all cost £10,000 more than it earned for us. That's

what they call the price of success.

PT : An album came out which was basically the singles

plus a couple more things besides?

RW : 'Nothing Can Stop Us'. A gratuitous title. Quite

ironic really, it's meant to look like a Leftie sort of

thing, but in fact it's lifted from some American talking

in 1932 - "we should not make the mistake the English

made of trying to govern the world, we shall merely own

it. Nothing can stop us now!" At the time it was quite

contentious, but I think it's turned out to be more or less

true.

|

|

PT : 'Animals'?

RW : 'That was Victor Schonfield, an American film

director who was making this 'Animals' film. He had a

friend of ours doing the narrative and he asked her if

she could find somebody who could do the film music. They

got permission to use a track of Talking Heads music for

the opening of the film, but they asked five hundred pounds

for something like three minutes. He paid it, but he still

had an hour and a half to fill. So I did the rest for

a hundred pounds!

PT : Then it's 'Old Rottenhat' after that?

RW : Yes it is. I'd put ideas out without having

a coherent reason for an LP. I was originally a drummer

and not a composer, it's only occasionally it comes together

enough. Thanks to the feedback from the singles though

I'd become active again and had generated enough of my

own material for an album, so I went and did it. I think

the title, 'Old Rottenhat', was influenced by Ian Dury

- he's one of the great lyricists in the English language,

a very underestimated writer. He's also very funny, and

I appreciate that. It was he who inspired me to use that

obscure old London expression that I'd heard Alfie use.

| |

"Ian

Dury ... is one of the great lyricists in the English

language." |

|

PT : So we're coming now towards the present time.

RW : Inexorably, yes. I did an EP called 'Work In

Progress' - Jeff wanted me to do something but I didn't

have enough for an LP so I did that instead. I really enjoyed

that - it was a nice studio. I did five things there including

a Cuban song, a Chilean song, 'Amber & The Amberlines'

(one of Hugh's tunes) and 'Pigs' for some Animal Rights

people [Deltic, Captain Sensible's label]

PT : And then your new album, 'Dondestan'?

RW : Well, I'd been moving house further north where

I could afford a room without any neighbours above for the

same money. Now I can make a lot of noise and put my cymbals

up - I've got a proper music room for the first time. The

result of that is 'Dondestan'. The trouble was, I'd got

the music, but I still hadn't really got around to the words.

Alfie, my wife, had written all these poems in a collection

called 'Out Of Season' which was ostensibly about being

in Spain in the winter, but it also seemed to me to be about

a lot of things... it would be pretentious to say what though,

I just hope it resonates in different ways for the people

listening to it. So I sang her poems to the music I was

working on and just juggled it about until it all came together.

There's one of Hugh's tunes on there as well, I like to

get one by him on a record - I'm superstitious about that

- at least I've got somebody else to blame then!

|

|

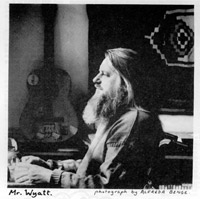

At this point, we had to leave to make way for a journalist

from some far glossier magazine than ourselves. We thank

Robert profusely, shake hands and emerge onto the sunlit

balcony of his flat. I'll leave the last words to Mr. Wyatt:

It's been a pleasure! A bit like a psychedelic experience

going through it an that fast - I must have missed quite

a bit out. I don't take any responsibility for lapses in

memory or outright lies!

Interview : Mick Dillingham and Phil

Intro : Dill - Article : Phil

With thanks to Chris Stone for tea, sunbathing, bananas

and organisation.

|