| |

|

|

Soft Machine - Uncut - The Archive Collection - 2019 Soft Machine - Uncut - The Archive Collection - 2019

|

|

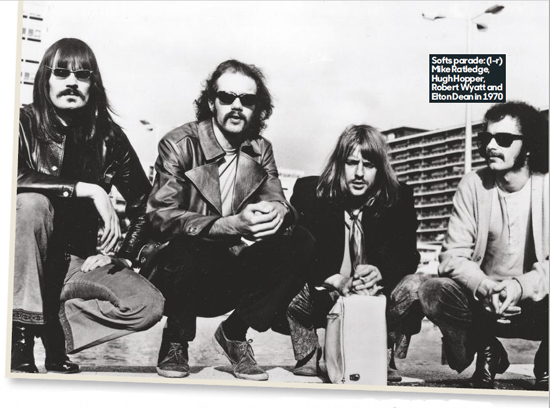

OFT MACHINE have been several

different groups over the course

of their existence – a freakbeat

combo who morphed into pioneers

of psychedelic whimsy; an

experimental prog band who eventually

became a rigorous jazz rock act. The bulk of

their output has been instrumental, but they

still managed to spawn three distinctive

vocalists – Robert Wyatt,

Kevin Ayers and Daevid Allen – who

questioned the fundamental nature of

Anglo-American rock music.

Uniquely among prog-rock bands, Soft

Machine tended not to use guitars, but

they’ve still managed to feature several of

Britain’s top guitarists – Andy Summers

from The Police, fusion guru Allan

Holdsworth and jazz luminary John

Etheridge. And the band has been the

seedbed for dozens of other hugely

successful musicians – film composer

Karl Jenkins, big-name saxophonists

Elton Dean, Ray Warleigh and Theo Travis,

and drummers John Marshall and Gary

Husband have all passed through the band’s

ranks over the past half century.

|

|

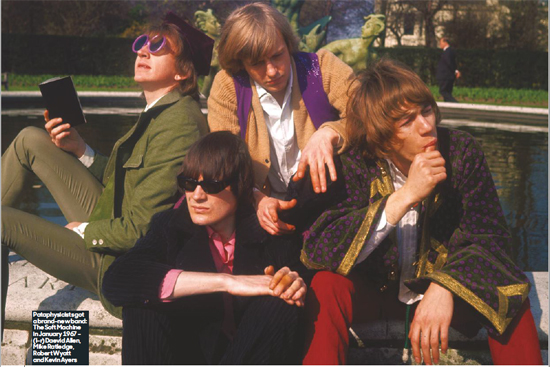

The band formed in 1966, from the ashes

of the Daevid Allen Trio and the Wilde

Flowers, featuring drummer Wyatt, bassist

Ayers, Aussie guitarist Allen and organist

Mike Ratledge. The only recording made by

this quartet would be the February 1967single, “Love Makes Sweet Music” – a piece

of charming freakbeat, not quite poppy

enough for Ready Steady Go!, yet not quite

freaky enough for the Summer of Love.

Its flipside, “Feelin’, Reelin’, Squealin’”,

is closer to the hippie ideal, a piece of

flute-drenched psychedelia featuring a

growling baritone-voiced Kevin Ayers on

the verses and a tenor-pitched Dadaist

chorus from Wyatt. It would also be the

last recording that the band would release

featuring a guitar for nearly a decade.

An early live engagement saw them on the

French Riviera, playing in a production of

Picasso’s outrageous, erotic play Desire

Caught By The Tail and already displaying

a fondness for jazz-inspired improvisation.

Allen left the band on the way home –

denied re-entry to the UK for overstaying the

terms of his initial visa from Australia, he

stayed on the Continent to form the Anglo-

French outfit Gong – but his surrealist vision

lived on for the first two Soft Machine

albums. In particular was Allen’s interest in

the teachings of the French “pataphysicist”

Alfred Jarry, an eccentric, proto-Dadaist

prankster who counted Picasso, Gauguin,

Duchamp and Oscar Wilde as friends.

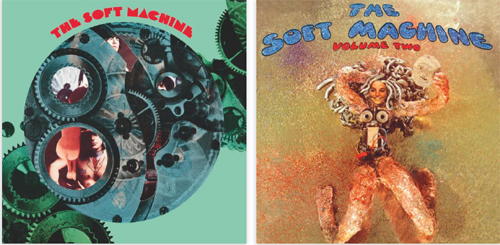

The three-piece band’s debut album,

1968’s The Soft Machine, is a wonderfully

endearing collection of skewed pop songs. It

was played with a certain rigour that owed

much to the band’s contemporaries the Jimi Hendrix Experience (whom the band

would support on a mammoth US tour that

year), but Wyatt, Ayers and Ratledge all

wore their experimentalism lightly – like

Alfred Jarry, this was a band who were very

consciously not taking themselves too

seriously. “Why Am I So Short?” is a hymnal

piece of Wyatt whimsy, “So Boot If At All”

has a certain heavy rock swagger, with

organist Mike Ratledge playing like a

metal guitarist; “Why Are We Sleeping”

prefigures early Blur; while “We Did It

Again” is a hypnotic one-chord groove

that anticipates the motorik krautrock that

Can would be making a few years later.

The album’s highlight might be “Lullaby

Letter”, an angular proto-punk miniature

with unusual chord changes that sounds

oddly reminiscent of Nirvana, with Ratledge

again playing a heavy metal solo on his

Lowrey organ.

After the US tour with Hendrix (when

Andy Summers briefly joined the band),

Ayers left, to be replaced by the

band’s roadie Hugh Hopper, and the

band regrouped to create the 1969

LP Soft Machine Volume Two, which

takes the Jarry-esque absurdism

of the first album into an almost

symphonic dimension. The

influence of the band’s friends Pink

Floyd is strong (Wyatt, Ratledge and

Hopper had backed Syd Barrett on his

1968 solo debut, The Madcap Laughs).

But the band also take a conceptual

direction that owes much to Frank Zappa

(apparently, on Zappa’s recommendation,

they split the album’s two dominating suites into a shorter series of segued tracks to

maximise on publishing income).

The first

of these, “Rivmic Melodies”, is a 17-minute

suite filled with compelling shorter pieces.

“Good evening, we now have a choice

selection of rhythmic melodies from the

Official Orchestra of the College of

Pataphysics,” announces Wyatt over a

jazzy, loping groove, before launching

into a Sesame Street-style recitation of

the alphabet over a quirky melody

(track four, “A Concise British

Alphabet, Pt II”, repeats the

track with the alphabet

recited in an entirely random

order). Anchored by Ratledge

playing suspended chords on

the piano, often with him

overdubbing buzzsaw organ

riffs over the top, it’s a

thoroughly appealing album,

and a fine vehicle for Wyatt’s

plaintive, mischievous choirboy

tenor voice. “Dedicated To You But

You Weren’t Listening” is a lovely

baroque ballad, while “Hibou

Anemone And Bear” and

“Orange Skin Food” both spin out into the

kind of territory explored by Frank Zappa on

Hot Rats, with Hugh’s brother Brian Hopper

playing harmonised solos on multiple reed

instruments. Best of all might be “Hulloder”,

presumably written in the States, where

Wyatt checks his privilege over the course

of a lengthy, stream-of-consciousness

ramble (“If I was black and I lived here/I’d

want to be a big man in the FBI… but as I’m

not/And because I’m free, white and 21/I

don’t need more power than I’ve got/Except

sometimes when I’m broke”).

The entire album is a cornucopia of ideas,

any one of which could have seen them

moving in a dozen different directions. The

direction that they did end up taking, like

many other jazz-loving rock musicians, was

inspired by Miles Davis’s album Bitches

Brew. At the end of 1969, Wyatt visited a

London jazz club where the pianist Keith

Tippett was performing with his eight-piece,

one that would later feature on his 1970

Polydor album You Are Here... I Am There.

Wyatt was impressed by the horn frontline

that lurched between tightly written

harmonies and free improvisation. “We

asked if we could borrow them to add spice

to our distinctive but inflexible ‘bees-in-a-bottle’

sound and they generously agreed to

help out,” says Wyatt.

Elton Dean (alto saxophone), Marc Charig

(cornet) and Nick Evans (trombone), along

with Lyn Dobson (flute and alto) and Jimmy

Hastings (flute and bass clarinet), were

added to the Soft Machine lineup, forming

a short-lived septet (Soft Machine weren’t

alone in their admiration of Tippett’s band – King Crimson also hired Tippett,

Charig and Evans around this time).

The resulting album, 1970’s Third,

turned out to be the way station between

psychedelic prog and full-on jazz rock.

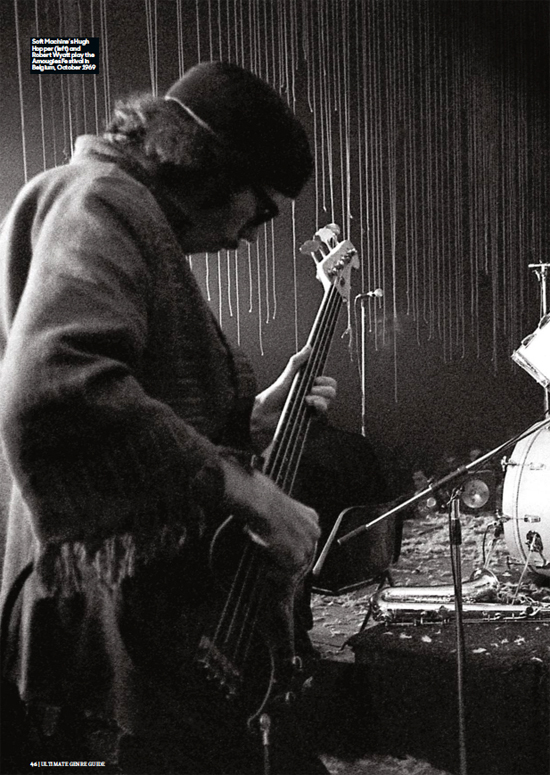

Hugh Hopper’s composition “Facelift”

is a challenging and intriguing mix of

ambient free improvisation and jazzy,

high-pressure rock. It is a blend of two

live performances recorded at Croydon’s

Fairfield Halls and then manipulated in

the studio, Teo Macero-style, and subject

to post-production tape loops. Ratledge’s

“Slightly All The Time” starts as a playful

swing groove that moves into several

stages and shifting time signatures; while

the closing track, “Out-Bloody-Rageous”,

starts and ends with a nod to Terry Riley’s

A Rainbow In Curved Air, with overdubbed

layers of organ creating a ghostly,

hypnotic quality for the first and last

five minutes of the track, sandwiching

a jagged 7/4 groove that features one of

Mike Ratledge’s best fuzz-organ solos.

The album’s penultimate track, Wyatt’s

“Moon In June”, might be the band’s

masterpiece, but it was one that Ratledge

and Hopper didn’t particularly like. Wyatt

sings a highly self-referential lyric that

provides a running commentary of the

recording process (the words would change

when he performed the song live, at BBC

Radio sessions, or at the Prom concert that

Soft Machine headlined that summer).

Wyatt plays drums, bass and keyboards

for most of the track, his sparse approach

reminiscent of his forthcoming solo albums

like Rock Bottom. “Moon In June” could

have augured a new era for the band as a

Wyatt-esque conceptual pop group, but

instead it became the band’s last vocal

track. 1971’s Fourth sidelines Wyatt and

it would be his last with the band. Hugh

Hopper is the dominant songwriter, and

many of the textures explored by the band

start to become self-consciously jazzier. Roy

Babbington joins the band on four tracks to

play upright bass, complementing Hopper’s

bass guitar, while Ratledge puts his electric

piano through a ring modulator – an FX unit

popular with the likes of Herbie Hancock

and Chick Corea. Elton Dean’s first

songwriting contribution, “Fletcher’s

Blemish”, is a series of tightly written

cued passages that are linked by free

improvisation, consciously referencing

Bitches Brew.

Ratledge writes the bitty,

fiddly “Teeth”, while Hopper’s “Virtually”

is a four-part suite that moves between

gentle harmonies and free-jazz freakouts.

The waltzing “Kings And Queens” is a rare

point of meditative peace on the album.

By the time of Fifth (1972), Soft Machine

had fully morphed into a fusion outfit,

broadly along the lines of Chick Corea’s

Return To Forever or John McLaughlin’s

Mahavishnu Orchestra. Wyatt had been

replaced by two jazz drummers – Phil

Howard on side one, John Marshall on side

two – both playing with a weird degree of

restraint. Ratledge had ditched his Hohner

pianet, the clunky-sounding electric piano

he’d used on previous albums, and started

using a Fender Rhodes, feeding it

through numerous effects units

and enjoying its glossy, ethereal

qualities on tracks like “M C” and

the aqueous ambient jazz of

“Drop”. “All White” is a rigorous

modal groove in 7/4, “Pigling

Bland” is an episodic funk ballad,

while “As If” is a fidgety and

idiosyncratic piece of collective

improvisation written by Ratledge.

What becomes apparent is that, for all the

meretricious playing, there is no-one in the

band capable of acting as a Chick Corea or a

Herbie Hancock. Ratledge is great at texture

and at “comping” (providing inventive

backing for others), and he could get away

with playing simple fuzz-rock riffs on his

wheezy, buzzy Lowrey organ in earlier

incarnations of the band. But, as a

classically trained pianist dabbling in

jazz, his limitations as an improviser

become apparent. Even the band’s strong

instrumentalists, like Elton Dean, seemed

reluctant to really take the lead.

Dean left after Fifth to be replaced by multireedist

Karl Jenkins from Ian Carr’s Nucleus,

who started to dominate the band on 1973’s

Six, a double album that mixes live and

studio recordings. A voyage through

enjoyably disorientating time signatures,

“37 ½” features some impressive drumming

from John Marshall; “EPV” and “Lefty” are

both interesting ambient explorations

featuring an FX-laden Fender Rhodes; while

the funky groove of Ratledge’s “Gesolreut”

recalls Eddie Harris’s “Freedom

Jazz Dance”, the soul-jazz

standard covered by Miles Davis.

The most memorable track on

the studio album is “Stanley

Stamp’s Gibbon Album” a

propulsive groove set around

Ratledge’s fugal piano riff. But

it’s the angular “Stumble” that

sets out Jenkins’ stall as a

songwriter, and sets the tone

for how the band would continue

on 1973’s Seven.

By now Hopper had left, to be

replaced by Roy Babbington, and

the writing is dominated by

Jenkins, who pens

seven of the tracks,

specialising in simple,

static and rather

repetitive grooves like

“

Nettle Bed”. “Carol

Ann” is a pretty,

spartan ballad, “Day’s

Eye” is a rigorous workout

in 9/8, while Ratledge

introduces a synth to the band

for the first time – a modular

analogue EMS model called the AKS.

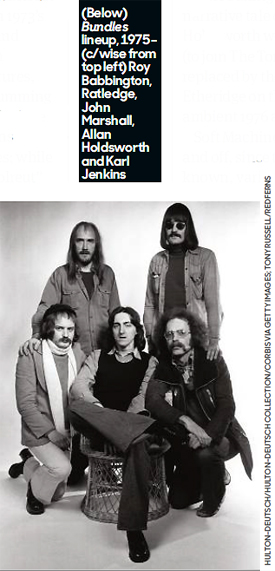

It’s tempting to see subsequent albums

as an afterthought, but Bundles (1975) is

a fascinating change in direction. Ratledge

is increasingly sidelined – Jenkins is even

starting to overdub keyboards – but the real

USP is that the band have introduced guitar

for the first time since their debut single.

Where the sonic space usually occupied by

guitar was filled by Ratledge’s FX-laden

keyboards, here Allan Holdsworth starts

to dominate proceedings, playing with

a John McLaughlin swagger on “Hazard

Profile”, showing an ECM delicacy on

“Gone Sailing” and telling a compelling

narrative tale on “Land Of The Bag Snake”.

Holdsworth would soon be lost to America

(to join The Tony Williams Lifetime), to be

replaced by the more introspective John

Etheridge on the rather reflective and

ambient 1976 album Softs.

Soft Machine have continued to exist, on

and off, since then, as a legacy project – also

known, variously, as Soft Ware, Soft Works

and Soft Machine Legacy –

drawing from an alumni of

around 50 people and often

featuring some very big

names in British jazz

(including John Taylor,

Dick Morrissey and Theo

Travis). But their repertoire

concentrates almost

exclusively on the mid 1970s

incarnation of the band.

There are dozens of

fascinating iterations of

Soft Machine that could

provide fruitful territory

for exploration.

[

Below : this interview is also published here]

|

|

|

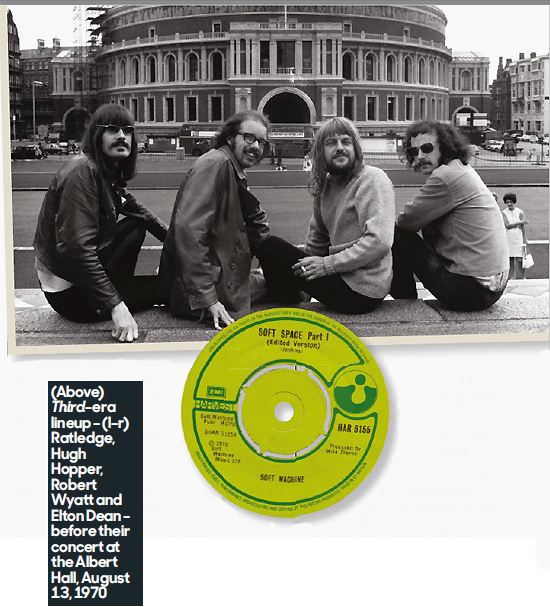

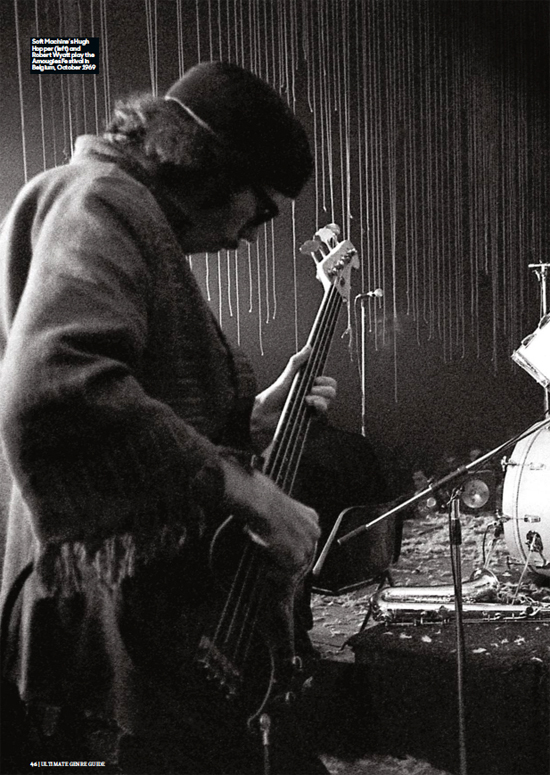

possessed under the hot lights of the Albert Hall

during the Softs’ televised concert; and then there

is Robert sitting with bitter tears in his eyes in a

dressing room in Rotterdam because he hates the

performance he has just given.

Because, you see, he’s nothing if not an

emotional person. He is also nothing if not

a nice person, and niceness is not an excessively

common quality among musicians and

entertainers. Much of the secret of his success

is that people respond so readily to his

spontaneity and generosity of spirit. Everybody

wants to work with him, and when they have

made the gig they come back for more. There was

nobody happier and more elated amongst those

50 people in Centipede than Wyatt, and no one

more brought down when the band received

reviews that were generally cautious and, in

one instance, bitterly hostile.

“I’m upset, not for my own sake,” he explained

later, “but for Keith and Julie.” And he meant it.

How do you feel about interviews, Robert?

“

I regret most I’ve done when I see what’s

happened, but then I regret most performances

on records, too. I think one of the big difficulties

is that written words and spoken words aren’t

the same thing. You actually think different

things in print – I do. Things I say, words I use in

speech, if I was writing down the same thought,

I actually wouldn’t use the same word. There’s

nothing anybody can do about that, really. It’s

misleading. I find I say things just to pad some

things out, or to be clever for a minute while I’m

trying to think what I really think. I can see the

value of them, but I still find it makes demands...

It upsets me sometimes, put it like that. But that’s

true of anything.”

But Hugh [Hopper] and Mike [Ratledge] don’t

like interviews, do they?

“Well, Hugh is

pathologically shy. Very. The fact that he goes on

stage is part of it. You don’t get up on your own,

you get up with equipment and amplifiers and

volume. It’s very private on stage; it’s not an

exhibitionistic thing to do at all.

“People are often surprised at musicians and

performers being introverts but it doesn’t surprise

me. What surprises me is that people who are

extroverts are musicians. What amazes me is

when a brilliant musician is an extrovert, because

if they’re extrovert it probably means that they

spent their time in their teens rushing round

coffee bars meeting people, and I’m

surprised that they had the time to learn

to play anything at the same time.

“Whereas I find that introverts are less

social people, are very often the ones who

learn to play instruments properly. The

one way you can hide is to be a performer,

because it’s really a false identity to be

on stage. You can really feel untouchable

and private.

“The group has become primarily

instrumental, for instance, because of

our characters, in a way. We’re a very

unplanned group in our direction. We just

sort of drift from whatever area seems to

excite us at the moment to whatever other

area seems to excite us. Even the simple

things, like the gaps, the lack of gaps, is

because we are embarrassed, I think, to

have a silence on stage where the audience is expected to react back to us. I just find that

totally embarrassing – ending a number, bang,

then straight into the next one, all that business.

I can’t bear it.”

You don’t always appear happy with the

group... What do you think it’s doing wrong

for you personally?

[Long pause] “All the things

you can talk about in music we agree on. We all

share similar ideas on the possibilities of freedom

and the different types of freedom, and structure,

and discipline, and what use they are, and when

they’re useful and when they are not, and how to

cooperate, and still express yourself. But music

isn’t, like, conscious ideas, concepts, if you had

them; the real music is the way you play, the

actual note that you put after the note before.

“And quite simply, sometimes we aren’t playing

the same piece of music – the drumming isn’t

the drumming for the bass line that Hugh’s

using, or there’s another bass line that isn’t being

played, or the rhythm section thing that should

be with Mike’s organ solo isn’t because Hugh and

I are somewhere else. The idea, after all, is not to

create four pieces of music but one piece of music,

and I’m upset on nights when we create four

pieces of music.”

So what have you gained musically from the

Symbiosis?

“Since the summer, since I’ve started

playing with Kevin, I’ve realised that in other

contexts there are things in me which come out

and never seem to come out when I play with Soft

Machine. It’s not a question of quality at all, it’s

just a question of different situations demand

different skills, and I hadn’t realised just how

much you do adapt and just play what seems

necessary. I would be very loath to put a word to

it and think of a concept which fits what I mean.

“All I know is that when I get on a kit, and there’s

Roy Babbington on me left and whoever it might

be, Neville Whitehead or someone, and Gary [Windo] and Nick [Evans], that a whole different

thing happens. I just lift up me sticks and

immediately something else happens and

different situations arise that would never

arise with Soft Machine. I just play completely

different things.

“Symbiosis is different people. All music is a

cooperative thing, you see. Beyond all people’s

individual talent is a shared talent, which

the music has. How to pin down the best

relationship... European music sort of solidified

in a way into an almost military hierarchy of

composer, conductor and orchestra.

“What happens is, there’s a kind of assumption

that the type of person who conceives the music

is a different kind of person from a performer –

that’s what European music assumes, although

many great European composers have been

virtuoso performers of their own work, and

many great composers are great conductors. But

generally speaking, this is a hierarchy that’s

accepted, and the fact is that in my opinion the

most vital influence on music has been the black

music of the past 50 years.

“The most interesting thing it seems to me,

that has been suggested by black music, is that,

as in, say, painting, the person who conceives

of it and the person who plays it can be one and

the same – combine both skills in one person.

And this seems to me the most interesting,

challenging thing that jazz music has come up

with that European music doesn’t really like to

get to grips with. And what Symbiosis is, is a

complete imbalance; in other words, we’re all

blowers without any of the composers, or when

we do have composers – like Keith was with us

the other night – he’s not in a composing or

controlling role at all.

“And so it’s an incredible risk, Symbiosis every

night, because we just turn up and play. The

responsibility is enormous; you’ve got to be on

form then and there because you’re going to be

doing all the composing and all the performing

at the same time, and so is everybody else.”

Would you agree that this seems to be a very

interesting period for young jazz musicians

and the thinking rock musicians? They really

seem to be coming together.

“Well, Centipede

is directly responsible for Symbiosis and so on.

Yeah, I think so. For me, I find it staggering, and

a bit scary, because it seems to me there’s so much

to do and so little to hide behind.

“There’s a lot of knowledge and wisdom

that’s been spread around in the last four

or five years. There’s no excuse for certain

types of musicians not knowing about

other types. The standards are so high

now! And the area of information you are

expected to cope with! I think there’s bound

to be a lot of messy stuff of journalistic

interest – interesting but disposable – but I

think it’s incredibly exciting. Short answer

to your question – yes.”

What do you think jazz people can

learn from those musicians with rock

references?

“That’s interesting. Before

I talk about it I think that if you think of it

as a blanket thing you’re in trouble; a band

created out of generalised theories sounds

like one to me, always. And a band made out

of people who’ve met and work together well sounds like that as well. There can be

as much difference in worlds between

two so-called rock musicians working

together, they can bring more

completely different things to each

other than a rock musician and a

classical musician.

“If there are any general things, I

think they’re the obvious ones. Jazz

musicians are now realising that there’s

nothing mature about consistently

drowning out your bass player and

pianist. There’s nothing childish about

getting your bass player and pianist

heard, even if it means they have to

play crude instruments such as bass

guitar and electric piano. There’s

nothing essentially immoral or

immature about it. The fact that rock

musicians assume that you’ve got to

hear the bass line – although very

often they overdo it – seems to me an

actual element of musical maturity

in rock. There’s an element of

childishness in jazz. There’s an

assumption that jazz musicians can do all the

teaching and rock musicians all the learning.

“If the soloist, for instance, is doing a

development upon a harmonic sequence and you

can’t hear the harmonic sequence, so you don’t

know what the solo lines are referring to, then you

lose the point of reference; you lose the lovely

cosmic hum, if you’ll pardon the expression; you

lose the sense of well-being, you lose, actually,

the music, and you just leave the ideas. It’s an

important thing in rock, the amplifiers and that,

and instead of being rude about them, I think

jazz musicians are realising more and more that

they’ve got a very important function and that

they’re solving problems that can’t be solved in

any other way in the immediate future.

“And I think rock musicians can learn from

jazz musicians. The most important thing they

learn is that you can get a lot more out of music

and put a lot more into it if you learn to play

properly. Quite simply, jazz musicians are

showing rock musicians that there’s an awful lot

of things you can do on a guitar and drum kits

that aren’t unnecessary or just technical fiddle

bits – they just expand your language.

“In practice, most jazz musicians tend to me to

be very involved in what they play – actually, the

relationship between them and their instrument;

and they’ve developed that to a very high extent –

a man and his bass, a man and his alto, a man and

his piano. And what rock has spent a lot more time

doing than most of jazz is studying the actual

effect and balance of what all these instruments

sound like from the outside on a stage.”

What do you think your strengths are as a

drummer?

“Well, I suppose it’s a bit late to say

this, but I don’t primarily think of myself as a

drummer. I think of myself as a catalyst for the real

musicians. How I see myself being most useful is

getting people at it slightly more than if I wasn’t

there, or even getting them together and at it. If I

was really into drums as an end I’d be sitting here

practising. But I haven’t got a practice pad! So long

as I can play well enough to pin down what’s going

on and to emphasise the pace that’s necessary.

“From the technical point of view I’m just

nowhere, really. I’ve always felt a bit uncomfortable since we started. Basically, I came

up to London to sing songs with Kevin [Ayers].

Five, six years ago. I’d done a lot of things before

then that were instrumental, but by instrumental

I don’t mean jazz or rock. In fact, the funny way

these discussions come to jazz and rock is that

I don’t see them as the two great sources from

which musicians are drawing.

“A lot of my richest sources of inspiration

come from not one musical idiom or the other

but from paintings, and theatre and people’s

characteristics that you haven’t seen come

through in music.”

But everybody is affected to a greater or

lesser extent by every experience they

encounter. Didn’t you once tell me you’d

learnt a lot by being told by Robert Graves,

the poet, to leave home at 16 and make your

own way in the world?

“Well, I lived with

him in Majorca for a while, and he became my

Mediterranean father in a way. He’s happy to have

me there, and I hadn’t left school when I first went

there, but he didn’t want me to loaf about in the

sun and just have a nice time and groove, which

is virtually the state he’s got to now, because he

has the traditional attitude that he’s done his

homework, built up something, and now he’s

out in the sun finishing it off, so to speak.

“I hadn’t earned it yet, somehow, and though

there was great love abounding it wasn’t one

which had to be constantly backed up by me

being there all the time or him coming here, just

that he felt I had to go out and do it, and then

when I’d got something that I’d done, maybe go

back and see him again. And I haven’t been back

yet because I don’t feel I’ve done anything yet

that would stand up to his kind of standards.”

So how did the tie-up with Graves originate?

“There’s a bunch of friends there in the early ’30s

who’d gone out there – poets and writers – and

their children, their grandchildren, got invited

out there by the people who stayed on there – you

know, the children of the people who went back

to England during the war. And I’m one of them.

He’s no relation, though my father’s first wife was

his secretary.

“There’s a kind of family of thinkers that my

parents belonged to, and to a certain extent

Robert Graves could be called the head of that

family. He’s a kind of distant tribal chief, though

it’s several generations removed. He had various

fights with me dad, who died some years ago. My

father at that time, he was a sort of brilliant young

Communist layabout, really [laughs].

“He’d done various things. He’d got a degree

in law at Liverpool, and then he did modern

languages at Oxford, and then he got on to do

psychology at Cambridge. A very bright bloke.

“He lived just long enough to realise that

I wasn’t going into university, which really

disappointed him. He died in a state of anger at

me, I’m afraid. But he was also a pianist, and

that’s definitely where I got my ideas from. The

house was full of music.

“And Graves, he’s incredible. There’s a colony,

a set, around him there. Mind you, I’m talking

about when I was there, which was before The

Soft Machine. I’ve got lots of friends who have

gone back there. Kevin spent some time there.

He got into Majorca as a place to live much more

than I did.”

So when you came up to London you were

going to sing with Kevin?

“Yes, I think that was

the idea; I didn’t really know. I’d been through a

period in my head very much like the stuff I’m

doing now, although not technically, probably.

The music I was listening to – had been listening

to – was Sunny Murray, Milford Graves and Cecil

Taylor, essentially. And Eric Dolphy, and Elvin

Jones, of course. And I arrived at the point where

I decided the simplicity of Kevin’s songs, and the

rightness and charm of them, had a fantastic

appeal to me after a couple of years of Sunny

Murraying and freak-out. And I’m now, I think,

at a similar stage. I’m likely now to get into the

stage that Chris Spedding has been through on

his album. I haven’t heard it, but what he’s said

about it I recognise, and I think a lot of us do.

“In fact, it’s becoming a long syndrome in music

– people going from complexity to simplicity. But

I still feel very lost, actually. Sometimes I’m back

where I started six years ago. I’ve to go through

the cycle all over again now.”

|