| |

|

|

Inside the mind of a Machine - Melody Maker - January 2,

1971 Inside the mind of a Machine - Melody Maker - January 2,

1971

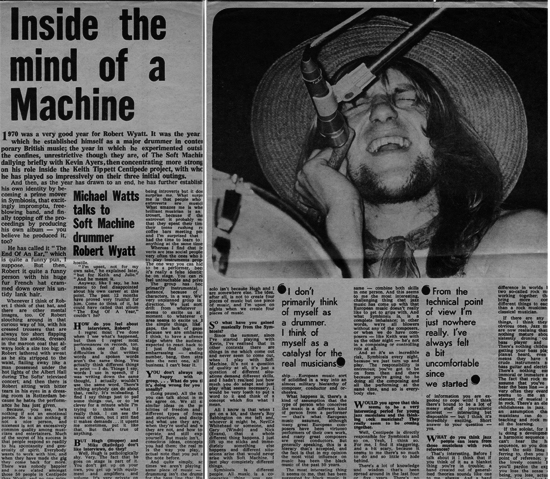

1970 was a very good year for Robert Wyatt.

It was the year in which he established himself as a major drummer in contemporary British music; the year in which he experimented outside the confines, unrestrictive though they are, of The Soft Machine, dallying briefly with Kevin Ayers, then concentrating more strongly on his role inside the Keith Tippett Centipede project, with whom he has played so impressively on their three initial outings.

And then, as the year has drawn to an end, he has further established his own identity by becoming a prime mover in Symbiosis, that excitingly impromptu, free-blowing band, and finally topping off the proceedings by producing his own album — you believe he produced it, too?

He has called it "The End Of An Ear," which is quite a funny pun, I suppose. But then, Robert it quite a funny person with his huge fur French hat crammed down over his untidy lank hair.

Whenever I think of Robert I think of that hat, and there are other mental images, too. Of Robert slouching around in that curious way of his, with his creased trousers that are always too short flapping around his ankles, dressed in the maroon coat that always look a size too big; of Robert lathered with sweat as he sits stripped to the waist, flailing away like a man possessed under the hot lights of the Albert Hall during The Softs' televised concert; and then there is Robert sitting with bitter tears in his eyes in a dressing room in Rotterdam because he hates the performance he has just given.

Because, you see, he's nothing if not an emotional person. He is also nothing if not a nice person, and niceness is not an excessively common quality among musicians and entertainers. Much of the secret of his success is that people respond so readily to his spontaneity and generosity of spirit. Everybody wants to work with him, and when they have made the gig they come back for more. There was nobody happier and more elated amongst those 50 people in Centipede than Wyatt, and no one more brought down when they band received reviews that were generally cautious and, in one instance, bitterly hostile.

" I'm upset, not for my own sake," he explained later, " but for Keith and Julie."

" And he meant it.

Anyway, like I say, he has reason to feel disappointed about his own career at this point. The past 12 months have proved very fruitful for him. Come to think of it, he could have called that album "The End Of A Year," couldn't he?

HOW do you feel about interviews, Robert?

I regret most I've done when I see what's happened, but then I regret most performances on records, too. I think one of the big difficulties is that written words and spoken words aren't the same thing. You actually think different things in print — I do. Things I say, words I use in speech, if I was writing down the same thought, I actually wouldn't use the same word. There's nothing anybody can do about that, really. It's misleading. I find I say things just to pad some things out, or to be clever for a minute while I'm trying to think what I really think. I can see the value of them, but I still find it makes demands... it upsets me sometimes, put it like that. But that's true of anything.

BUT Hugh (Hopper and Mike (Ratledge) don't like interviews, do they?

Well, Hugh is pathologically shy. Very. The fact that he goes on stage is part of it. You don't get up on your own, you get up with equipment and amplifiers and volume. It's very private on stage; it's not an exhibisionistic thing to do at all.

People are often surprised at musicians and performers being introverts but it doesn’t surprise me. What surprises me is that people who are extroverts are musicians. What amazes me is when a brilliant musician is an extrovert, because if they’re extrovert it probably means that they spent their time in their teens rushing round coffee bars meeting people, and I'm surprised that they had the time to learn to playt anything at the same time.

Whereas I find that introverts are less social people are very often the ones who learn to play instruments properly. The one way you can hide is to be a performer, because it's really a false identity to be on stage. You can really feel untouchable and private.

The group has become primarily instrumental, for instance, because of our characters, in a way. We're a very unplanned group in our direction. We just sort of drift from whatever area seems to excite us at the moment to whatever other area seems to excite us. Even the simple things, like the gaps, the lack of gaps, is because we are embarrassed, I think, to have a silence on stage where the audience is expected to react back to us.

I just find that totally embarrassing — ending a number, bang, then straight into the next one, all that business. I can't bear it.

YOU don't always appear happy with the group… What do you think it's doing wrong for you personally?

(Long pause). All the things you can talk about in music we agree on. We all share similar ideas on the possibilities of freedom and the different types of freedom, and structure, and discipline, and what use they are, and when they're useful and when they are not, and how to operate, and still express yourself. But music isn't, like, conscious ideas, concepts if you had them; the real music is the way you play, the actual note that you put after the note before.

And quite simply, sometimes we aren't playing the same piece of music — the drumming isn't the drumming for the bass line that Hugh’s using, or there's another bass line that isn’t being played, or the rhythm section thing that should be with Mike’s organ

solo isn't because Hugh and I are somewhere else. The idea, after all, is not to create four pieces of music but one piece of music, and I'm upset on nights when we create four pieces of music.

SO what have you gained musically from the Symbiosis?

Since the summer, since I've started playing with Kevin, I've realised that in other contexts there are things in me which come out and never seem to come out, when I play with Soft Machine. It's not a question of quality at all, it's just a question of different situations demand different skills, and I hadn't realised just how much you do adapt and just play what seems necessary. I would be very loath to put a word to it and think of a concept which fits what I mean.

All I know is that when I get on a kit, and there's Roy Babbington on me left and, whoever it might be, Neville Whitehead or someone, and Gary (Windo) and Nick (Evans), that a whole different thing happens. I just lift up me sticks and immediately something else happens and different situations arise that would never arise with Soft Machine. I just play completely different things.

" I don't primarily think of myself as a drummer.

I think of myself as a catalyst

for the real musicians " |

Symbiosis is different people. All music is a cooperative thing, you see. Beyond all people's individual talent, which the music has. How to pin down the best relationship…

European music sort of solidified in a way into an almost military hierarchy of composer, conductor and orchestra.

What happens is, there's a kind of assumption that the type of person who conceives the music is a different kind of person from a performer — that's what European music assumes, although many great European composers have been virtuoso performers of their own work, and many great composers are great conductors. But generally speaking, this is a hieracy that's accepted, and the fact is that in my opinion the most vital influence on music has been the black music of the past 50 years.

The most interesting thing it seems to me, that has been suggested by black music, is that, as in, say, painting, the person who conceives of it and the person who plays it can be one and the same — combine both skills in one person. And this seems to me the most interesting, challenging thing that jazz music has come up with that European music doesn't really like to get to grips with. And what Symbiosis is, is a complete imbalance; in other words, we're all blowers without any of the composers, or when we do have composers — like Keith was with us the other night — he's not in a composing or controlling role at all.

And so it's an incredible risk, Symbiosis every night, because we just turn up and play. The responsibility is enormous; you've got to be on form then and there because you're going to be doing all the composing and all the performing at the same time, and so is everybody else.

WOULD you agree that this seems to be a very interesting period for young jazz musicians and the thinking rock musicians?

They really seem to be coming together.

Well, Centipede is directly responsible for Symbiosis and so on. Yeah, I think so. For me, I find it staggering, and a hit scary, because it seems to me there's so much to do and so little to hide behind.

There's a lot of knowledge and wisdom that's been spread around in the last four or five years. There's no excuse for certain types of musicians not knowing about other types. The standards are so high now! And the aera of information you are expected to cope with! I think there's bound to be a lot of messy stuff of journalistic interest — interesting but disposable — but I think it's incredibly exciting. Short answer to your question — yes.

From the technical point of view

I'm just nowhere really.

I've always felt a bit uncomfortable

since we started |

|

WHAT do you think jazz people can learn from those musicians with rock references?

That's interesting. Before I talk about it I think that if you think of it as a blanket thing you're in trouble; a band created out of generalised theories sounds like one to me, always. And a band made out of people who've met and work together well sounds like that as well. There can be as much difference in worlds between two so-called rock musicians working together; they can bring more completely different things to each other than a rock musician and a classical musician.

If there are any general things, I think they’re the obvious ones. Jazz musicians are now realising that there’s nothing mature about consistently droning out your bass player and pianist. There's nothing childish getting your bass player and pianist heard, even if it means they have to play crude instruments such as bass guitar and electric piano. There’s nothing essentially immoral or immature about it. The fact that rock musicians assume that you've got to hear the bass line — although very often they overdo it — seems to me an actual element of musical maturity in rock. There’s an element of childishness in jazz. There’s an assumption that jazz musicians can do all the teaching and rock musicians all the learning.

If the soloist, for instance, is doing a development upon a harmonic sequence and you can't hear the harmonic sequence, so you don’t know what the solo lines are referring to, then you lose the point of reference; you lose the lovely cosmic hum, if you'll pardon the expression; you lose the sense of well-being, you lose, actually, the music, and you just leave the ideas. It's an important thing in rock, the amplifiers and that, and instead of being rude about them. I think jazz musicians are realising more and more that they've got a very important function and that they're solving problems that can't be solved in any other way in the immediate future.

And I think rock musicians can learn from jazz musicians. The most important thing they learn is that you can get a lot more out of music and put a lot more into it if you learn to play properly. Quite simply, jazz musicians are showing rock musicians that there's an awful lot of things you can do on a guitar and drum kits that aren't unnecessary or just technical fiddle bits — they just expand your language.

In practice, most jazz musicians tend to me to be very involved in what they play — actually, the relationship between them and their instrument; and they've developed that to a very high extent —a man and his bass, a man and his alto a man and his piano. And what rock has spent a lot more time doing than most of jazz is studying the actual effect and balance of what all these instruments sound like from the outside on a stage.

WHAT aspects of your playing, do you think, have improved since working with the jazz musicians in Centipede?

Funnily enough, this is where categories break down, because it's almost like for the first time I've had to be a rock drummer. It's the first time my primary function has been to lay it down so that, as much as my role permitted, everybody knew where things were, what was going on, what the dynamics and feel were. A functional role to a degree I've never had before. In fact, until this year I've never worked with other people's bands before.

I've been spoilt very much. I've developed everything I've done either in playing in groups without leaders or groups where everybody had an equal say. Keith certainly didn't tell me what to do, but it seemed after the first run-throughs the right approach to take in relation to what Brian (Spring) and Tony (Fennell) were doing. And funnily enough, it's taught me about rock drumming — about that kind of functional drumming as opposed to counter-point drumming. Christ, I haven't played in 4/4 for about two years!

WHAT do you think your strengths are as a drummer?

Well, I suppose it's a bit late to say this, but I don't primarily think of myself as a drummer. I think of myself as a catalyst for the real musicians. How I see myself being most useful is getting people at it slightly more than if I wasn't there, or even getting them together and at it. If I was really into drums as an end I'd be sitting here practising. But I haven't got a practice pad! So long as I can play well enough to pin down what's going on and to emphasise the pace that's necessary.

From the technical point of view I'm just nowhere, really. I've always felt a bit uncomfortable since we started. Basically, I came up to London to sing songs with Kevin (Ayers). Five, six years ago. I'd done a lot of things before then that were instrumental, but by instrumental I don't mean jazz or rock. In fact, the funny way these discussions come to jazz and rock is that I don't see them as the two great sources from which musicians are drawing.

A lot of my richest sources of inspiration come from not one musical idiom or the other but from paintings, and theatre and people's characteristics that you haven't seen come through in music.

BUT everybody is affected to a greater or lesser extent by every experience they encounter. Didn't you once tell me you'd learnt a lot by being told by Robert Graves, the poet, to leave home at 16 and make your own way in the world?

Well, I lived with him in Majorca for a while, and he became my Mediterranean father in a way. He's happy to have me there, and I hadn't left school when I first went there, but he didn't want me to loaf about in the sun and just have a nice time and groove, which is virtually the state he's got to now, because he has the traditional attitude that he's done his homework, built up something, and now he's out in the sun finishing it off, so to speak.

I hadn't earned it yet, somehow, and though there was great love abounding it wasn't one which had to be constantly backed up by me being there all the time or him coming here, just that he felt I had to go out and do it, and then when I'd got something that I'd done, maybe go back and see him, again. And I haven't been back yet because I don't feel I've done anything yet that would stand up to his kind of standards.

SO how did the tie-up with Graves originate?

There's a bunch of friends there in the early thirties who’d gone out there —poets and writers — and their children, their grandchildren, got invited out there by the people who stayed on there — you know, the children of the people who went back to England during the war. And I'm one of them. He's no relation, though my father's first wife was his secretary.

There's a kind of family of thinkers that my parents belonged to, and to a certain extent Robert Graves could be called the head of that family. He's a kind of distant tribal chief, though it's several generations removed. He had various fights with me dad, who died some years ago. My father at that time, he was a sort of brilliant young Communist layabout, really, (laughs). He's done various things. He'd got a degree in law at Liverpool, and then he did modern languages at Oxford, and then he got on to do psychology at Cambridge. A very bright bloke.

He lived just long enough to realise that I wasn't going into university, which really disappointed him. He died in a state of anger at me, I'm afraid. But he was also a pianist, and that's definitely where I got my ideas from. The house was full of music.

And Graves, he's incredible. There's a colony, a set around him there. Mind you, I'm talking about when I was there, which was before The Soft Machine. I've got lots of friends who have gone back there. Kevin spent some time there. He got into Majorca as a place to live much more than I did.

SO when you came up to London you were going to sing with Kevin?

Yes, I think that was the idea; I didn't really know. I'd been through a period in my head very much like the stuff I'm doing now, although not technically, probably. The music I was listening to — had been listening to — was Sonny Murray, Milford Graves, and Cecil Taylor, essentially. And Eric Dolphy, and Elvin Jones, of course. And I arrived at the point where I decided the simplicity of Kevin's songs, and the rightness and charm of them, had a fantastic appeal to me after a couple of years of Sonny Murraying and freak-out. And I'm now, I think, at a similar stage. I'm likely now to get into the stage that Chris Spedding has been through on his album. I haven't heard it, but what he's said about it I recognise, and I think a lot of us do.

In fact, it's becoming a long syndrome in music — people going from complexity to simplicity. But I still feel very lost, actually. Sometimes I'm back where I started six years ago. I've to go through the cycle all over again now.

Michael Watts

|