| |

|

|

Soft Machine - Time Out - July 11th-25th, 1970 Soft Machine - Time Out - July 11th-25th, 1970

SOFT MACHINE

|

|

THE SOFT MACHINE

(Robert Wyatt - drums, Mike Ratledge - organ, Hugh Hopper - bass, Elton Dean - alto sax and saxello.)

Now that the Soft Machine have been chosen to play at the Proms this summer, maybe the pop scene will finally wake up enough to give their music some of the recognition it's lacked for so long. Apart from a small group of devoted fans the group have been ignored in Britain for three years now simply because few people have stopped to listen to them. The pop writers don't go to their concerts, record companies don't release their albums and most of the record-buying public had never heard of them. Thanks to Richard Williams of Melody Maker and John Peel, a little notice is now being taken of what the Soft Machine are doing, but their recent residency downstairs at the Ronnie Scott club still passed largely without comment. And yet they are the only pop group ever invited to play there.

The group's music isn't easy to listen to and probably makes a lot of people feel very uncomfortable. It defies categorisation, using the electronic paraphernalia of modern pop as a medium for hour-long pieces that rival the works of the best twentieth century classical composers in scope and complexity. As much could be said of King Crimson and the Pink Floyd, but when you add the Soft Machine's willingness to experiment with unusual time signatures, their use of brass, Mike Ratledge's incredible organ solos and Robert Wyatt's drumming, they are in a class of their own. It's strange that it takes Ronnie Scott and the organisers of the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts to give a group of such obvious quality the status it deserves.

London first heard the Soft Machine three years ago when they played regularly at the now legendary UFO club in Tottenham Court Road. At that time the group comprised three school friends from Canterbury Grammar - Wyatt, Ratledge and Kevin Ayers on lead - and Daevid Allen, an Australian, who played bass. Despite their over-indulgence in unorthodox sound effects and rather pretentious refusal to break between numbers, the music was raw and exciting, a refreshing change from the banalities of the contemporary pop scene. The group also made the fullest possible use of the lights, strobes and weird stage outfits then coming into vogue to intensify the direct physical assault their music made on slightly bewildered audiences. Inevitably enough, their only attempt to make the charts, Love Makes Sweet Music, released in April 1967, flopped and, by the time promoters were beginning to realise that a large audience existed for 'underground' groups, they were in France. While flower-power boomed in Britain the Soft Machine were playing on the beach at Saint-Tropez, warming up audiences for a new play by Pablo Picasso, Désir Attrapé Par La Queue. When the local mayor stepped in and closed it down they moved to a marquee just outside the town, playing for very little money but making a big hit with the media people from Paris who gave the group invaluable exposure on French TV. They've played a lot in France since then and now rate as one of their top three groups.

The British Immigration Authorities forced the first change in personnel by refusing to allow Daevid Allen back into the country. An Australian, he'd been working with the group without a permit. So Kevin Ayers switched to bass and they carried on as a trio, playing art schools for under £50 a night. The group worked better as a trio, getting a tighter sound with more scope for Mike Ratledge's increasingly complex organ solos and Robert Wyatt's voice. Kevin Ayers was a strong influence on the group at this time, writing songs like We Did It Again and Lullabye Letter and appearing on stage without a shirt, his eyes extravagantly made-up. Robert Wyatt went one better by playing in swimming trunks.

Early in 1968 Mike Jeffery, manager of Jimi Hendrix and the Animals, signed the Soft Machine to support Hendrix on his American tour. At first it looked like the break they'd been waiting for but the tour soon degenerated into one long hassle, playing night after night and travelling incredible distances, with no time to rehearse and very little sleep. Only a historic gig at the Museum Of Modern Art, New York, and the release of the group's first LP saved it from being a total wash-out. A faithful reproduction of their stage act, the LP was recorded in a week and they were unhappy with the results. Tom Wilson was supposed to produce the record but he hardly ever showed up, leaving the Soft Machine who'd rarely seen the inside of a studio to do most of the work themselves. Nevertheless, The Soft Machine Volume I is an excellent record, probably the best released that year, with certainly the most original sleeve. It sold well in the States and on the continent, but was never released in this country. Under the influence of Mike Jeffery, the group had signed with the Probe label who distributed their records in Britain through EMI. In 1968, however, Probe were beginning to setup their own outlets here and refused in the meantime to let anyone else handle their records. So, despite frantic telegrams from the group back in England, nothing happened. Their second LP nearly went the same way, finally being released here a year after it had been recorded.

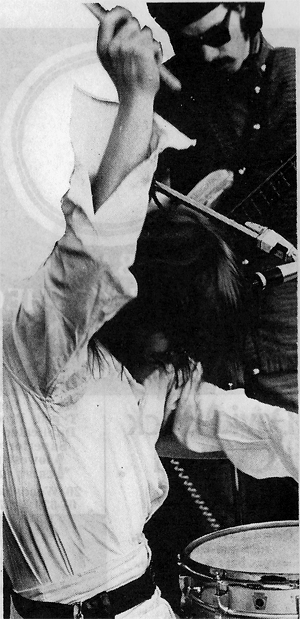

Mike Ratledge - organ (Photo: Dominique Tarle)

|

The Soft Machine broke up in the States, unable to take the strain of touring any longer. They reformed almost immediately but without Kevin Ayers who felt unhappy with the musical direction of the group. 'Esther's Nose Job' had been lying around for over a year but Kevin had never been able to play it, nor was he willing to learn. "It was fine when we were playing the very free things", he recently told Richard Williams, "but it got into a lot of writing and jazz things like odd time signatures and I really wasn'tup to that". To replace him Wyatt and Ratledge brought in another school friend, Hugh Hopper, who had been their road manager in the States. He'd written 'A Certain Kind' for the first LP, had been rehearsing on bass with the group for some time and, most important of all, he could read music.

Very soon afterwards they recorded the second LP for Probe. Apart from a few superficial similarities - each side of the record being conceived as an entity for example - it was very different from their first. The Soft Machine Volume 1 captured the intensity of the old stage act but remains a succession of songs, swept along and linked together by Wyatt's ferocious drumming. On Volume 2 Wyatt had cut down on the vocals and his drumming was less in evidence. Hopper's bass was fuzzier and less pedestrian than Ayers had been and Mike Ratledge was beginning to break away from the restrictions of the 30-second organ solo. The group was tighter yet more relaxed than before and the Hopper-Ratledge writing team obviously had potential. Although it was messy and pretentious in parts and lacked the immediate appeal of their first LP, the record deserved a lot more attention than it was given.

During the last year the Soft Machine have become virtually unrecognisable as the group Kevin Ayers used to play in, despite playing with him on his Joy Of A Toy LP for Harvest. They still use some of the numbers from their second LP but most of the material is new and written by Hopper and Ratledge. Although he has written in the past, Robert Wyatt has more or less given up now. Realising that it was impossible to sing and drum well at the same time and worried that his voice sounded out of tune, he has cut down on the vocals as well and limits himself to a few scat solos at each performance. Mike Ratledge now rates as one of the best organists in pop or jazz and Hugh Hopper has improved tremendously since he first played with the group. One of the nicest things about the group is their willingness to experiment musically, and while Wyatt has been phasing out his vocals, their use of brass has increased. For a while last year they appeared with the entire front line up from Keith Tippett's group but after a few months the practical problems of keeping a large band well-rehearsed proved too demanding and they made do with Lyn Dobson (flute and soprano sax) and Elton Dean (alto and saxello) who is still with them.

|

Robert Wyatt - drums; Hugh Hopper - bass.

(Photo: Pete Sanders) |

|

Despite having concerts at Croydon and the Queen Elizabeth Hall and the residency at Scott's under their belts, a tour of the provinces under way and a Promenade Concert to look forward to on 13 August, the group's new double LP is an important step, the first product of a contract they recently signed with CBS.

Reasonably priced at 59/6d, Third is similar in conception to the Floyd's Ummagumma. Mike Ratledge is responsible for two sides, Slightly All The Time and Out-Bloody-Rageous, Hugh Hopper for Facelift, alive recording of two performances in January, and Robert Wyatt contributes Moon In June. Facelift begins with an amazing organ solo by Mike Ratledge who is joined by Elton Dean's alto and Lyn Dobson on soprano who build up for Hugh Hopper to introduce the main theme. The riff is given urgency the first time round by the organ, bass and horns before Ratledge moves into a long solo, followed by some excellent work on flute and soprano sax by Lyn Dobson. Out-Bloody-Rageous is the best of the studio tracks, a beautiful and restrained piece which opens with progressions of the theme on piano tapes played backwards. Again, Hopper's bass introduces the rest of the group. Interest is held by some clever changes in tempo and towards the end Dean plays a moving alto solo while the mood is brought to a climax by the organ, bass and drums. The group's strength is their mastery over incredibly complex time changes, sometimes overshadowing the horns which are left repeating the theme of a piece while Mike Ratledge solos into the next tempo. As we see on Slightly All The Time, which features a long solo by Elton Dean and some fine work on flute by Jimmy Hastings, the Soft Machine give considerable freedom to their sidemen - a welcome change from the rest of the 'pop meets jazz' brigade. At times Elton Dean does appear a little uncomfortable with his material but the structure of the Soft Machine's music would hardly accommodate the solos he plays with Keith Tippett.

Robert Wyatt's track should really have been called "Volume One Revisited" and it'll please the people who wish that they had stuck to that style. Moon In June is the only time that we hear Robert's voice on the record and its lyrics are in the old throwaway style - "before we go on to the next part of our song, let's all make sure we've got the time". He accompanies himself on organ, electric piano and drums until Hugh Hopper switches to fuzz bass and Mike Ratledge comes in with a solo played very much in his Volume One style while Robert plays with echo on his voice. I suspect that a lot of people are going to like this track best of all since only here do the group dispense with the brass and go back to the freedom of some of their old pieces.

Third is a staggering musical achievement that transcends anything yet produced by a British rock group and is essential listening for anyone who wants to hear what a fusion of the best of modern jazz and rock can produce. In fact it can't really be discussed in terms of those categories at all since the Soft Machine have virtually created their own. Their music has a long way to go, as Mike Ratledge is the first to recognise, and we'll see a lot of changes as soon as they are in a position to take more time off for recording and writing. But whatever happens to the group in the future, after Third no-one can pretend to ignore them.

Jim Talbot

|

|