| |

|

|

The Soft Machine : contemporary classical musicians - Friends N° 9 - 10 July 1970 The Soft Machine : contemporary classical musicians - Friends N° 9 - 10 July 1970

|

|

Andrew Lycette

The first Soft Machine record was a single issued by Polydor in 1966 called 'Love Makes Sweet Music.' It was a conventional pop ditty of the sort which would undoubtedly make the Top Twenty today. But the Soft Machine has moved on from those long distant days when they used to play with Mark Boyle's light show at the Roundhouse or in Joan Littlewood's evening multi-media scenes at Stratford East. They were really only fooling around then, now they are serious professional musicians. Hugh Hopper who himself only joined the group in 1968 after their American tour, told of the paradox, "In those days we were the freaks and serious people came to watch us; now we are the serious ones, and the freaks come to watch us." (Fair enough, he admits that it is best to listen to the Soft Machine stoned, "unless you have an open mind anyway. The best thing about the group are its sound qualities and its dynamics. Well, you can appreciate the dynamics anyway but to get inside the sound "you've got to be either stoned or very receptive." Robert agrees. He says, "You get five times your money's worth if you listen to us smashed").

That's the thing about the group; they are in no way what they seem. English hads try to make them into freaks, but as Mike Ratledge says, it just happened that they were around when the Press latched on to the word 'psychedelic' to describe everything that was going on around the U.F.O. scene. French conoisseurs think they are revolutionaries and pataphysicians.

First a touch of group history though. Mike, Robert Wyatt and Hugh were all together at the Simon Langton Grammar School in Canterbury. They started playing what Mike calls vaguely 'free jazz' when they were 16 to 17 years old. They never actually appeared in public though and limited their venues to each other's houses. Now even after a decade together off and on, they are still none too happy about playing in public. Mike admits like Hugh to stage fright, and that's why they don't try to act like pop stars.

After this beginning Mike who was a couple of years older than the others went up to Oxford University where he read Psychology arid Philosophy and gained a middle second class degree. He didn't like the place.

Rather than go to the USA he rejoined Robert in group including Kevin Ayers, and two Australians, Dave Allen and Larry Newlin. Dave was a guitarist whom the group had met in 1963, when, as a modern jazz quartet, they played at the then fashionable Establishment Club. They split up the same year though when Mike was up at Oxford. Hugh and Robert, who had dropped out of school, tried for a while to make it with a pop group (soul et al) called the Wild Flowers, but they got nowhere except very hungry. Kevin and Robert then split to Majorca, still trying to cash in on the post-Beatles pop

boom, Hugh to Paris where he got into acid at the early date of 1963.

DINGO VIRGIN & THE FORE SKINS

When they all got back to London and the new group was formed with Mike down from Oxford, they ran through a lot of names — Mr. Head and Dingo Virgin and the Foreskins being two — before arriving at the Soft Machine. It was a title that seemed to fit at the time, and, as Dave knew Burroughs, they got permission to adopt it. But as Mike says, he has explained it away to journalists all over the world in a variety of different manners. Probably the best of these is still the original meaning that Burroughs held when he took the words from physiology where they appear as a generic term for the human race. We're all the human race, therefore we're all Soft Machine.

Ratledge & Co. are still up there, but on a strictly musical sense now, and this helps explain the genesis of the current group. Ratledge especially tended to find the quintet too amateur, too poppy. Larry soon quit, and Kevin and Dave were not quite the musicians the group required.

Still they continued to play in England (the 1966 U.F.O. boom) and on the continent (as in 1967, when they appeared for a week in one of Ian Knight's inflatable balloons on the beach at St. Tropez, but were forced by police pressure to move on and to find refuge as resident musicians at the Picasso play/orgy 'Le désir attrapé par la queue'). David was not allowed to return to England after this as he had been playing without a work permit, so his freaky - there is no other word for it - influence retired from the group.

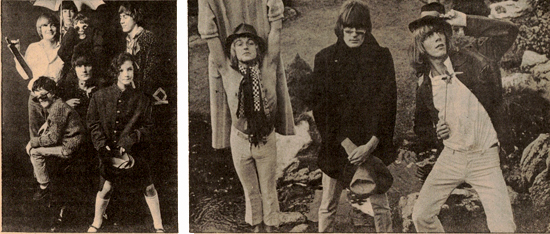

The original Soft Machine - Wyatt, Ratledge and Ayers |

Kevin, who had really got the Soft Machine together in the first place and forced Mike and Robert to find decent equipment and contracts, went after the 1968 American tour, in which they appeared with Hendrix night after night for five months in a succession of gymnasia with foul acoustics. They returned really pissed off and very tired (except for Robert who amused himself greatly at Hendrix's expense in the L.A.); in fact, they disbanded completely for a while. Kevin split again to the continent, and Mike and Robert were soon keen to reconstitute the band, the original trio, with Hugh Hopper, who'd been their roadie in America and who almost reluctantly agreed to rejoin them as a musician, because they were going to attempt some different sorts of material. "When the Soft Machine first formed," he says, "I didn't really like what they were doing. It was very pretentious, the David Allen thing, the Kevin thing. Not till I actually became their road manager did I get into it."

It seems that he and Mike were now able to assert their influences more. Mike began to compose for the group (for, in spite of what it says on the label, he had little to do with the first L.P.). He is the sort of person who hates sentimentality (of the Incredible String Band type) neither Kevin's romantic lyricism (which Robert loves and which is beautifully manifest on Joy of a Toy where the Soft Machine appear to show there are no hard feelings), nor Dave Allen's anarchistic "Give me a blue mist on a snowy mountain top, Mike" type of approach were quite his scene.

DEBUSSY, RAVEL & HINDEMITH

Mike, who had been learning the piano since the age of 7, who was into Debussy, Ravel, and his favourite, Hindemith when he was at school, and who studied under the world famous classical musician, Treharne, while he was at Oxford was able to bring the music the core of the Soft Machine's act, especially as Hugh was able to read a score which made working much faster. "We had problems over the lyrics, and we found it was difficult to get into word situations. Kevin was more interested in reaching people immediately through verbal participation, but we were not prepared to spend enough time working out a reasonable compromise between this and the music we wanted to play. Robert was singing too much to concentrate properly on his drumming. So now we've made a sort of blind leap of faith. A pop group as we are makes the basic assumption that people are the same, and you succeed by doing what you like."

So now they've moved on from a situation where they were providing jazz backings for Kevin's and David's songs, through a period when they used to sing about the most banal matters possible (as, for example, on a Top Gear last year when they sang a song extolling the virtues of the B.B.C. canteen just along the corridor, using a tune, incidentally, that has cropped up again on the new album with different words and different connotations — good artists never waste their material), to their present practice of playing pure written music with complicated structures and with only very occasional breathless renditions from Wyatt's screaching larynx. Mike puts this down to the fact that "everyone's changed, we're all more experienced," which is undoubtedly true. This has meant that the Soft Machine has left behind the clever poppiness of 'I Did It Again' (supposedly based on a Terry Riley composition, but in fact, Hugh says, rather more influenced by James Brown) and have used their professionalism to venture into unknown areas in their search for what Hugh calls quite simply "nostalgic sounds."

So they've now added an excellent saxophonist in the Coltrane tradition (Elton Dean from the Keith Tippett group) to give themselves extra freedom within which to expand their sound. They did try at one time to use four brass, but that created too much of a big band noise (it was too expensive, anyway); then they went down to two brass which they all liked and which was easy to reproduce on stage, but Lyn Dobson, the flautist and soprano saxophonist did not fit into the group ("there were personal problems," said Mike tactfully). Now they are happy to have just Elton to add to their sound. He enjoys playing with them on a non-permanent basis and is free to play with other groups when he wants.

THE PROMS

The move into the realms of freely structured amplified jazz-pop has of course led to some antipathy from the traditionalists among the Soft Machine's fans (especially, it appears, in France where in true Gallic fashion the cognoscenti remain conservative while imagining that they are radical). The band is undaunted though. It goes on next month to appear at the Proms (the original Henry Wood version) which will be a mind-zapper for the dinner-jacketed audience in the Albert Hall. (Not that the musicians make much about it; Robert, who is careful to say that he enjoys being in a so-called art group, says that it will just be another gig for them and that it will be interesting to gauge the audience's reactions). They would like to do some film music too, but so far they have turned down a number of continental offers in the hope of something bigger and better (though it is true you can see them, along with the Floyd, in a pirated French version of the Amougies festival). Hopper says that he personally would like to do the music for a film by Losey or Polanski.

Apart from that they really haven't many plans, though they hope to release another album pretty soon.

Sean Murphy, their manager, who shows where he is at with his intention to publish

an artist's guide to contracts, has signed them up at C.B.S., who are just as happy with the deal as are the group, and has developed the group's policy of concentrating as much on continental audiences as on British ones (with great results, especially in Holland where their second L.P. topped the charts and where in fact they are doing their only festival this year).

|

|

But then they are not really interested as a group in playing live at all. Ratledge and Hopper insist that they must spend at least as much time relaxing at home, writing their compositions, rehearsing their ideas as appearing on stage. (Again this is the result of the American tour on which they found themselves becoming increasingly stale and unoriginal as they were unable to rehearse or write new material, and it is especially necessary now that when Mike composes a piece he also writes out the parts for the others, especially for Elton who consequently gets through a great deal of work). Hugh in fact admits that he is probably more interested in producing than in playing. His side of the new L.P. is therefore probably the most technically ambitious, adding a number of loops to the group's Fairfield Hall concert in January.

SMALL SCALE INSTITUTION

Robert is quite different. He wants to get back on the road where he feels his real

interests lie. "To round off my life I feel the need to get out there, but not in the context of the Soft Machine, that has become too big, it's become a small scale institution. I don't think of myself as a professional musician, I am rather in the tradition the folk musician, the minstrel, if you can make such distinctions, and I think you can." Therefore he proposes to do a lot of work with Kevin Ayers' new group, and with another musician whom he was loth to name because it might compromise him in his position in his present group. Elton feels much the same and will continue to work with Keith Tippett, and with Zoot Money.

In the meantime the whole group are quite happy with their double L.P. The second one they had to rush through on a small budget. Hugh hadn't actually ever even played live with the group, and they were unable to do the things they wanted to do, so they don't particularly like the result. The first album (although incredibly it reached number 38 in the States) is simply old hat to them.

But it is too easy to group the quartet together in a composite 'they' and it doesn't really work. Mike is still very much the university non-conformist, though on a personal level rather than a political one. He is officially married to Marsha Hunt, who is a friend whom he helped stay in the country by going, through the offices. He refuses to admit to any sort of classification either for his music or for himself. When we were talking about Mark Boyle (on whom he had written an enthusiastic article for the French magazine Actuel), he stressed that he offered no self-contained aesthetic criticism. "It really depends who you talk to in this group, man. I mean Robert tends to make everything into a consistent system. I'm really not interested in that at all, i.e., you know, I don't want to systematise all my likes and make it into one great big system. So it tends to be just things I like, and I happened to like Mark Boyle's stuff, his light shows were very good." All this delivered very fast (he has an uncanny source of energy for a cat who can exist for two days on one omelette and a couple of packs of Benson and Hedges), very intelligently, very precisely. It was typical of him to insert the abbreviation 'i.e.' as an example of his desire to get what he was saying right. Thus when I asked about the literary influences on the early Soft Machine (the Jarry, the French symbolists and surrealists who creep in and appear to have been very important, especially with the evidence of one of their amps which has the words DADA scrawled on its back, but this is only a truly dada touch, because the amp had been stolen in France by a group called DADA LIVES who managed to write half their name before the equipment was refound), he remonstrated, "I mean how do you divide a person up. I mean that's like saying - shit what else do I like doing — you know, if I like motor-cars, you can call it motorcar music. I mean I happen to like reading literature - beautiful tautology that - well, reading anyway, but I don't see why that makes it a literary basis." He admits that he sees the lyrics as rather a fill-in; "Christ, man, words are such a hassle." He prefers to talk of his music as "organic," and spends a lot of time working at the structure of his pieces, developing ideas from Terry Riley, and making sure that the sounds are right. As Hugh said, "Mike is much more interested in melody, he's interested — in written music, in getting a structure. He's been through the intermediate stage (e.g. people like Cage) and now he's listening more to written music which has go to have some form. Myself I'm less worried by form than the others."

The seven piece Soft Machine at Ronnie Scott's |

VERY ECHOEY SOUNDS

Hugh, the other main creative influence in the group, very quiet, unforthcoming, patient, apathetic in Mike's words (but not in terms of the music he writes and produces. He doesn't like Americans (their self-confidence he finds obnoxious, though he admits it's probably because he is jealous), he reads Evelyn Waugh and a lot of similar novels, and he answers questions very slowly, very honestly. Acid, for example, had "split me down the middle; sometimes I was really happy, sometimes I was very depressed." This seems to reflect his usual attitude to life. "Several times in the last year I've said to myself that is the last time I am going to play. That's the build-up from a number of depressing situations. But the alternative is even more depressing; I would have to make money in even more depressing situations" — something he has done before and has no desire to return to. Mike may be interested in structure, Hugh is more into sounds qua sounds (thus his desire to produce and his brilliantly inventive bass guitar work on the new L.P.). "When there is a very still passage, not much rhythmic movement, you just get very echoey sounds by playing very loudly and very high notes — I think that is the only thing I really enjoy playing." Actual tunes do not turn him on so much, at least not after he has sussed out what they're all about. "When you make music it's very strange, because once you've written it and worked it out it doesn't have the same interest, it's done. I used to find this particularly when I played semi-pro, when I played other people's music. Take MacCartney's 'Yesterday'; when I heard that I thought it was the most beautiful thing I'd ever heard. When I actually learnt to play it, it was still a nice tune, but it didn't have any magic. Trouble is, that happens as soon as you write a tune yourself. The best thing is to write it and then lock it away for a year."

Robert is completely different again, bubbly, amusing, sympathetic and, like Mike said, with a tendency to use his intelligence to categorise everything in his mind. He thinks that the way most rock groups are run is amazingly fascist. Not that he sees himself as any kind of revolutionary. "I'm a very conventional socialist. I don't think like others that capitalism is a system that has got to be totally overthrown before happiness will ensue. Each system is as prone to misuse as any other." He thinks the Labour party legislates nearer to the Christian ideals than any other party in the world (any other left wing party would have made an ideological issue out of the abolition of hanging, he says), and this consideration is very important to his mind. "Christianity has a fantastic ethic-I haven't come across anything better." This rationalist approach to his politics means that, in spite of his wander-lust, he has little time for heads, whom he found "tiring and somewhat humourless. I don't like that kind of naive dabbling with occult, I like the company of really sharp people. In fact, I'd rather watch Morecombe and Wise than read through the Confessions of Alistair Crowley." When he was abroad therefore, he wasn't in Ibiza or Morocco, but rather with his second father, the poet, Robert Graves, who looked after his when his own father died and who educated him with his brilliance, his wit and his liveliness. It also means that he can be pretty scathing about pop gurus and hangers-on. The people who write Rolling Stone, he feels are thirty years old and trying to convince themselves and others that the rubbish they listened to when they were younger was worthwhile. (This remark mirrors his prejudices against modern American music which he hardly listens to — "I don't know what we'd have done without black music, but I have enough respect for it not to try and copy it" — though he loves Hendrix, Sly and the Family Stone and all jazz). He finds it funny too that "the one thing the current revolutionaries are most perturbed by is the fact that their heroes in the pop business are part of the big capitalist set-up." The real revolutionaries in music, as far as he is concerned are not the MC5 — a Mafia hype — but people whom the young revolutionaries have never heard about, people like Charlie Havens and John Surman.

CHURNING AWAY & PHYSICAL

Robert has some original ideas about the music the Soft Machine are putting over too. He is the only member of the group who doesn't seem to believe that the group has progressed in its sound in the last year or so. He agrees that it has gained in popularity; "up to six months ago it was hardly worth our doing a gig in England." "Now it is true we play more notes more often, but actually the base patterns and the rhythm patterns which everything turn on are very traditional. You know, Hugh and I are one of the most straight-forward rhythm sections I've ever heard in jazz or pop. Compare us now to the earlier Soft Machine. There was much more complex dynamics a year or so ago." So he admits, "I think we are a rock group. We're always playing the basis we're working on. In jazz people build up their variations, and gradually drop away what they're variations on, whereas we're rock in the sense that whatever we're improvising on or building things on we keep very strongly in evidence. That's why I always wanted to be a rock player; because whatever we're doing on top, it's always churning away and physical underneath. So we're not only a rock group, but a very traditional one at that. Changing time signatures doesn't mean very much, and in some jazz groups it even masks the inability to play good music."

Photographs by Byron |

Robert agrees that the addition of Elton has been very important though, not least because it has allowed him to give over his voice part to the saxophone. Elton is a typical South London head, unpretentious and mildly self-deprecating. He was called to join the group after the Soft Machine had seen him playing at the Plumpton festival last year. His new arrival means that he has some quite astute things to say about their playing. For instance, he sees his spiritual colleague in the group as Robert, because "he's a spontaneous bloke who blows and fills in little bits, while Mike and Hugh keep to a set pattern." This is in contradistinction to Robert's idea of his function as a member of the rhythm section, and to my own opinion that Mike and Elton can be paired together because they both play mind-blowing phrases over and above the main themes (though that's really Robert in reverse).

It would be a bit sick at this stage to trv to classify the Soft Machine in any particular way. They are not particularly concerned with making it bigger than Jesus Christ; they don't think they've found either an intellectual or a musical answer. Consequently the margin of malaise in their music, from the words on the first L.P. "My head is a night club with tables and chairs,' through the frenzied organ and drum take-off at the end of Kevin's Song for Insane Times on his album of Joy of a Toy, to the new tight and original musical sound dominated by the conflicting leaps and bounds of the organ and saxophone. They are not escapists ("We are not up there to make everyone forget their troubles," says Robert who agrees this is a function for some groups and who therefore really digs Mungo Jerry). They are rather opportunist drifters in the beat style (see Mike's life lines on the first L.P.) interested in creativity for it's own sake (not quite l'art pour l'art). As Robert puts it, their ideal situation would be as painters, because these artists gets the best out of their medium, they are able to concentrate all their talents to producing one particular effect, or series of effects. Yet still "We're part of the European concert group tradition, but using bits of information that others don't know about, such as the rock rhythm techniques of Sly and the Family Stone. Yea, we're contemporary classical musicians."

Ad published in the same issue

Ad published in the same issue

|

|