| |

|

|

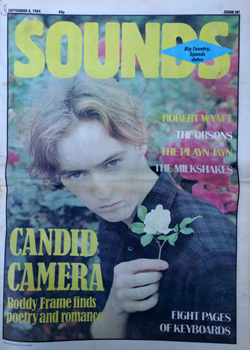

Life's A Wyatt ! - Sounds - September 8, 1984 Life's A Wyatt ! - Sounds - September 8, 1984

LIFE'S A WYATT !

|

|

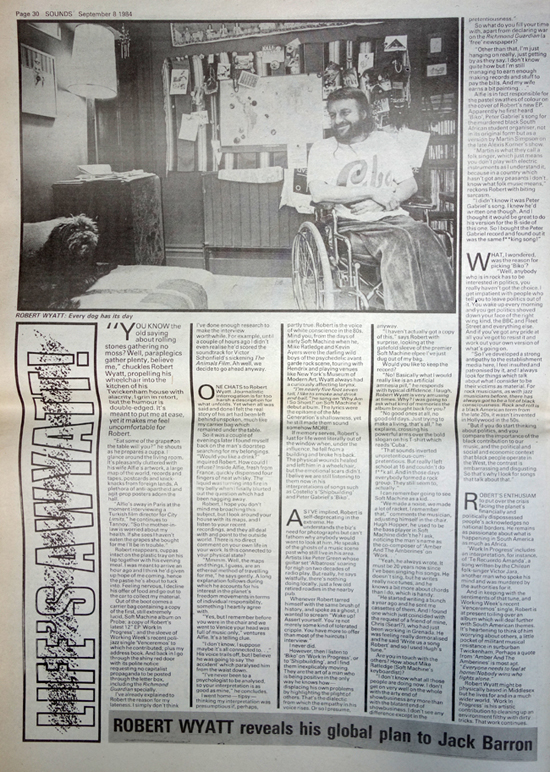

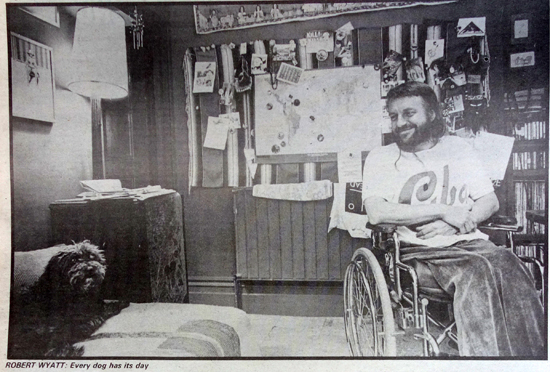

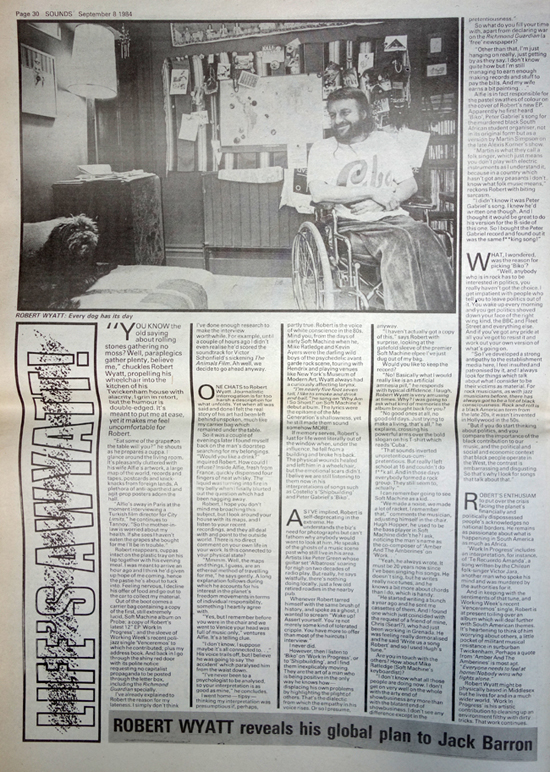

« YOU KNOW the old saying about rolling stones gathering no moss? Well, paraplegics gather plenty, believe me, » chuckles Robert Wyatt, propelling his wheelchair into the kitchen of his Twickenham house with alacrity. I grin in retort, but the humour is double-edged. It's meant to put me at ease, yet it makes me feel uncomfortable for Robert.

"Eat some of the grapes on the table will you?" he shouts as he prepares a cuppa. I glance around the living room. It's pleasantly cluttered with his wife Alfie's artwork, a large map of the world, records and tapes, postcards and knick-knacks from foreign lands. A plethora of anti-apartheid and agit-prop posters adorn the hall.

"Alfie's away in Paris at the moment interviewing a Turkish film director for City Limits," he continues to Tannoy. "So the mother-in-law is worried about my health. If she sees I haven't eaten the grapes she bought for me I'll be in trouble."

Robert reappears, cuppas intact on the plastic tray on his lap together with his evening meal. I was meant to arrive an hour ago and I think he'd given up hope of me coming, hence the pastie he's about to tuck into. Feeling nervous, I decline his offer of food and go out to the car to collect my material.

Out of the boot comes a carrier bag containing a copy of the first, still extremely lucid, Soft Machine album on Probe; a copy of Robert's latest 12"EP 'Work in Progress'; and the sleeve of Working Week's recent poli-jazz single 'Venceremos' to which he contributed; plus my address book. And back in I go through the shiny red door with its polite notice requesting no capitalist propaganda to be posted through the letter box, including the Richmond Guardian specially.

I've already explained to Robert the reason for my

Lateness. I simply don’t think I've done enough research to make the interview worthwhile. For example, until a couple of hours ago I didn't even realise he'd scored the soundtrack for Victor Schonfield's sickening The Animals Film. Ah well, we decide to go ahead anyway.

ONE CHATS to Robert Wyatt. Journalistic interrogation is far too harsh a description for what unfolds. Yet when all was said and done I felt the real story of his art had been left behind unspoken, much like my carrier bag which remained under the table.

So it was a couple of evenings later I found myself back on the man's doorstep searching for my belongings. "Would you like a drink?" inquired Robert. How could I refuse? Inside Alfie, fresh from France, quickly dispensed four fingers of neat whisky. The liquid was turning into fire in my belly when I finally blurted out the question which had been nagging away.

Robert, I hope you don't mind me broaching this subject, but I look around your house with its maps, and I listen to your recent recordings, and they all deal with and point to the outside world. There is no direct comment on your own life in your work. Is this connected to your physical state?

"Mmmm. Well, the maps and things, I guess, are an ethereal method of travelling for me," he says gently. A long explanation follows during which he accounts for his interest in the planet's freedom movements in terms of individual responsibility, something I heartily agree with.

"Yes, but I remember before you were in the chair and we went to Venice your head was full of music only," ventures Alfie. It's a telling clue.

"I don't know, I suppose maybe it's all connected to…" His voice trails off, but I believe he was going to say 'the accident' which paralysed him from the waist down.

"I've never been to a psychologist to be analysed, so your interpretation is as good as mine," he concludes.

I went home — tipsy — thinking my interpretation was presumptious if, perhaps, partly true. Robert is the voice of white conscience in the 80s. Mind you, from the days of early Soft Machine when he, Mike Ratledge and Kevin Ayers were the darling wild boys of the psychedelic avant garde rock scene, touring with Hendrix and playing venues like New York's Museum of Modem Art, Wyatt always had a curiously affecting larynx.

"I'm nearly five foot seven tall, I like to smoke and drink and ball, "he sang on 'Why Am I So Short ?' on Soft Machine's debut album. The lyrics were the epitome of the Me Generation’s shallowness, yet he still made them sound somehow MORE.

If memory serves, Robert's lust for life went literally out of the window when, under the influence, he fell from a building and broke his back. The physical wounds healed and left him in a wheelchair, but the emotional scars didn't. I belive we are still listening to them now in his interpretations of songs such as Costello's 'Shipbuilding' and Peter Gabriel's'Biko'.

AS I'VE implied, Robert is self-deprecating in the extreme. He understands the biz's need for photographs but can't fathom why anybody would want to look at him. He speaks of the ghosts of a music scene past who still live in his area. Artists like Peter Green whose guitar set 'Albatross' soaring for nigh on two decades of radio play. But really, he says wistfully, there's nothing doing locally, just a few old retired roadies in the nearby pub.

Whenever Robert tarred himself with the same brush of history, and spoke as a ghost, I wanted to scream "Wake up! Assert yourself. You're not merely some kind of tolerated cripple. You have more to offer than most of the haircuts I interview."

I never did.

However, then I listen to 'Biko' on 'Work In Progress', or to 'Shipbuilding', and I find them inexplicably moving. They are the art of a man who is being positive in the only way he knows how — displacing his own problems by highlighting the plight of others. That's the dialectic from which the empathy in his voice rises. Or so I presume,

anyway.

"I haven't actually got a copy of this," says Robert with surprise, looking at the

gatefold sleeve of the premier Soft Machine elpee I've just dug out of my bag.

Would you like to keep the record?

|

"No! Basically what I would really like is an artificial amnesia pill," he responds with typical diffidence. I laugh, Robert Wyatt is very amusing at times. Why? I was going to ask what kind of memories the album brought back for you ?

"No good ones at all, no good old days. Just trying to make a living, that’s all, » he explains, crossing his powerful arms over the bold slogan on his T-shirt which reads 'Cuba'.

"That sounds inverted unpretentious-cum-pretentious. But really I left school at 16 and couldn't do f**k all. And in those days everybody formed a rock group. They still seem to, actually."

I can remember going to see Soft Machine as a kid…

"We made a noise, we made a lot of racket, I remember that," comments the musician, adjusting himself in the chair. Hugh Hopper, he used to be the bass player in Soft Machine didn't he ? I ask, noticing the man's name as the co-composer of 'Amber And The Amberines' on 'Work…’

" Yeah, he always wrote. It must be 20 years now since I've been singing his songs. He doesn't sing, but he writes really nice tunes, and he knows a bit more about chords than I do, which is handy.

"He started writing a bunch a year ago and he sent me cassettes of them. And I found one which just coincided with the request of a friend of mine, Chris (Searl?), who had just been working in Grenada. He was feeling really demoralised and he said 'Write us a song Robert' and so I used Hugh’s tune."

Are you in touch with the others? How about Mike Ratledge (Soft Machine's keyboardist)?

"I don't know what all those people are doing now. I don't get on very well on the whole with the arty end of showbusiness any more than with the blatant end of showbusiness. I don't see any difference except in the pretentiousness. »

So, what do you fill your time with, apart from declaring war on the Richmond Guardian (a ‘free’ newspaper) ?

« Other than that, I’m just hanging on really, just getting by as they say. I don’t know quite how but I’m still managing to earn enough making records and stuff to pay the bills. And my wife earns a bit painting… »

Alfie is in fact responsible for the pastel swathes of colour on the cover of Robert’s new EP. Apparently he first heard ‘Biko », Peter Gabriel’s song for the murdered black South African student organiser, not in its original form, but as a version by Martin Simpson on the late Alexis Korner’s show.

« Martin is what they call a folk singer, which just means you don’t play with electric instruments as I understand it, because in a country which hasn’t go any peasants I don’t know what folk music means, » reckons Robert with biting sarcasm.

« I didn’t know it was Peter Gabriel’s song. I knew he’d written one thought. And I thought it would be great to do his version for the B-side of this one. Si I bought the Peter Gabriel record and I found out it was the same f**king song ! »

WHAT, I wondered, was the reason for picking ‘Biko’ ?

« Well, anybody who is in rock has to be interested in politics, you really haven’t got the choice. I get impatient with people who tell you to leave politics out of it. You wake up every morning and you get politics shoved down your face of the right wing kind, the BBC and Fleet Street and everything else. And if you've got any pride at all you've got to resist it and work out your own version of what's going on.

"So I've developed a strong antipathy to the establishment media here, I feel insulted and patronised by it, and I always look for things which talk about what I consider to be their victims as material. For rock musicians, as with jazz musicians before, there has always got to be a lot of black consciousness. Rock and roll is a black American term from the late 20s, it wasn’t invented in Hollywood in the 50s.

"But if you do start thinking about politics, and you compare the importance of the black contribution to our music, and the political and social and economic context that black people operate in the West, the contrast is embarrassing and disgusting. So that's why I look for songs that talk about that."

ROBERT'S ENTHUSIAM to put over the crisis facing the planet's financially and politically dispossessed people's acknowledges no national borders. He remains as passionate about what is happening in South America as much as Africa.

'Work In Progress' includes an interpretation, for instance, of 'Te Recuerdo Amanda', a song written by the Chilean folk-singer Victor Jara, another man who spoke his mind and was murdered by the authorities for it.

And in keeping with the sentiments of that tune, and Working Week's recent Venceremos' single, Robert is at present toiling over an album which will deal further with South American themes. It's heartening to think of him worrying about others, a little pocket of militant musical resistance in suburban Twickenham. Perhaps a quote from 'Amber And The Amberines' is most apt. " Every one needs to feel at home/Nobody wins who fights alone."

Robert Wyatt might be physically based in Middlesex but he lives for and in a much wider world. 'Work In Progress' is his artistic contribution to cleaning up an environment filthy with dirty tricks. That work continues.

|