| |

|

|

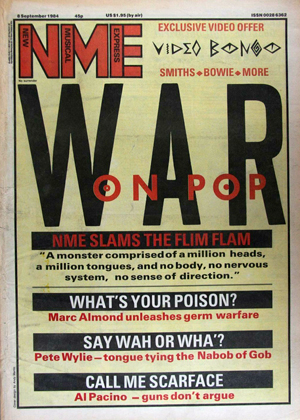

Robert Wyatt: Mongrel Musics - New Musical Express - 8th September,

1984 Robert Wyatt: Mongrel Musics - New Musical Express - 8th September,

1984

|

|

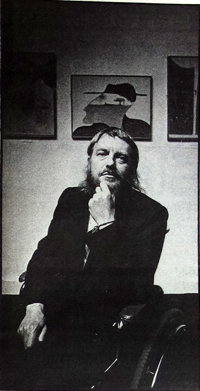

Nobody could have told me how Robert Wyatt's cover of Cuban pop star Pablo Milanes 'Yolanda' was going to capture my ear more tenaciously than any double-edged love song since Smokey Robinson's summer masterpiece 'And I Don't Love You'.

But certainly no-one could have warned me that Wyatt's work is done for the same reason as Eddie Van Halen's.

Eddie: "It all comes down to one thing: I hear this particular noise in my head. Then I drive myself and everyone else crazy trying to duplicate it."

Robert Wyatt: "It's always been my priority to just duplicate the noise I hear in my head. To be honest I still haven't managed to do it; I've been hearing it a long time and I've always found it a constant struggle, picking out instruments, testing microphones and stuff.

"But I want to SAY that because sometimes these interviews get so um...far away from the basic effort you're engaged in. Which is to try and make a certain sort of pleasant noise for a certain length of time."

Both Eddie and Robert say, by the way, it's an obsession that can drive their respective spouses "up the wall".

Bristol-born Wyatt gained musical recognition as a school kid – and when his garage combo split, the half he went with turned into Soft Machine. He drummed for that bunch of jazz-rock pioneers till '71, when he formed Matching Mole. They had two LPs and a Chinese fire-drill of personnel under their belts when, in 1973, Wyatt's plummet from an upstairs window during a party left him permanently paralysed from the waist down.

Since then we've heard from a different artist; one, as he put it to Brian Case in 1976, "in the position of painters and writers who work on their stuff and then present it for response".

The stuff in question has included two rather diverse chart hits: versions of the Monkees' 'I'm A Believer' and the Costello-Langer meditation 'Shipbuilding'. Wyatt's new release is an EP, Work In Progress. Almost titled 'South Of The Border', it strongly reflects its creator's attraction to the Spanish language (he covers Chilean hero Victor Jara's poignant 'Te Recuerdo Amanda' as well as 'Yolanda'). Even Peter Gabriel's 'Biko' has been re-tuned to resonate with the need for North to embrace South.

"I'm told my accent isn't so good in legitimate Spanish," ventures the bright-eyed Mr Wyatt as he taps a Gauloise loose from the pack. "But remember Matt Monro, 'the singing bus driver'? Look, he's a big star in Spain where I now live. He does cover versions of every meaningful ballad under the sun – and he's found a whole new career on the Costa Brava. So maybe... " Wyatt grins.

He does that a lot, in fact. So where, I wonder, did I get this idea I was going to meet an eminent worthy, willing to share some air largely with talk of warring political ideologies? Could it have been 'Stalin Wasn't Stallin', off his previous long-player? Is Mr Wyatt – however unlikely it's beginning to seem – a sloganeering sort of agit-pop person?

"It varies according to the situation of the listener, actually," is his reply. "Like, I just finished speaking with these two Italian geezers for whom politics is really on the agenda – its vocabulary is inextricably linked with what they DO every day. Now, they think: is this song any use to us or not? What's this guy up to? And I'm willing to be tried and found wanting on their terms.

"Because – musicians make a living selling songs, we're no substitute for serious political action, private or public (laughs). Neither, of course, are newspapers. But the consequences of what we do or say are not enormous. People say 'Look at the enormous political influence of Bob Marley' but when Seaga still goes to the IMF, begging bowl in hand, I don't go for it. There's way too much arrogance about the supposed abilities of musical spellbinders to shift the balances of power.

"Against the real forces – people in tall buildings somewhere deciding who to punish by where they put their bucks – there's not much any of us singing our songs can do. It's just (laughs again) I see nothing else really interesting in life except trying to go for what I can in that respect."

But that involves musicianship much more than Clash-style sloganeering?

"Well, whatever any record's about you want it to sound good; first off it's always that. I don't want to listen to anything which isn't pleasurable to hear simply because someone else thinks I should. There are (a smile) bodies in that field but it's a different one altogether from where I am. And if people want to keep in touch with life and ideas I would hardly recommend following pop lyrics!

"The reason I'm happy to say quite simple and I unambiguous words," he continues, "has grown out

of sheer exasperation. That what I thought was clear enough in the past just wasn't. So now I'm trying to do something where you couldn't possibly not know whose side I was on in any situation. Life is so full of misunderstanding and ambiguities already... I'm not gonna deliberately set out to build some kind of mysterious chic around what I'm saying."

Um. I understand Spanish. But what about the definite mystery factor anyone who doesn't will encounter when you sing in that language?

"Oh," says Robert. "I love the sound of it, just musically, even when I can't understand it. I sang my first song in it a couple of years ago before I knew what the words meant, I basically went with it for musical reasons. But: loosely, cultural and political ideas do tend to travel round a network of people who speak the same language or languages. And with the Spanish-speaking world, that language barrier is partly at the root of wrong doings from the North. I think even within the Caribbean, it's language barriers which are the greatest bar to unity."

YOU STARTED out drumming and never ever sang, then you got into drone musics and scatsinging. Now the quality and colour of the voice seem almost your main instrument. Has this evolved from your beginnings in a fan-based approach? Were you drawn to it by an ear for that sort of tone and accent in sound?

"That's right actually. Because I like that fluidity and ambiguity very much. I haven't got a very big record collection – mainly what people have sent me really. And the music I tend to listen to does seem much less cut-and-dried, much less finalised than rock seems to have to be."

Listening to all your work as 'in progress', you seem to be trying to bring together things which people separate for their own purposes – which may be political. Things like leisure and politics, thinking and enjoyment...

"All those conflicts are built into everything you do – just listen to me! One minute I'm talking about being as clear as possible and the next minute about enjoying ambiguity. But in fact we're all subject to all those impulses and desires and influences and for me I don't have a clear division between aesthetics and politics or just practical realities.

"Because aesthetics is just a sophisticated word for stimulating the pleasure content of an experience – while cruelty, sadism and suffering eat away at people's capacity to enjoy life. So, it seems to me that any point made against sadism or cruelty is an aesthetic point. I see them as directly related."

But right now there's this pervasive belief that you can legislate people's enjoyment – by and large that is all the music business does or tries to do at the moment. It's one thing very wrong with the Frankie phenomenon and God knows it's damaged any potential for dealing with the arts through television.

"It's very difficult, that. Because you can't set up a Utopian situation, you sort of jaywalk your way through the oncoming traffic and grab onto what bits and pieces you know in your heart matter or that you know you can make work.

"See, I've always tried to keep a distance from things I knew could chew me up and spit me out five minutes later. It's not some higher code... it's just commonsense survival logic. But it means I can say that I see clearly how the long term effects of the novelty industry of 'now' are not even the long term interests of the people being used by it.

"I noticed right from my beginnings with bigger record companies that the people who are slowly and steadily building a position for themselves weren't the musicians. They were the people running the companies.

|

|

"So I've never had any reason to go along with any record company's way of doing things – or to believe it would be in my interest to do so. Even though it may seem that there is no alternative and even though people tend to go Yes! Yes! when they even see a contract."

Jovially, Wyatt taps another cigarette against the glass table. "I would say it's quite similar to prostitution actually," he grins. "You've got this two or three year period where you're meant to bloom and really by the time you find out what the game is you've lost any power you have because what they consider to be your 'bloom' has faded. And anyway, they've got a whole new bunch of innocents.

"The people running things just build and build and build- but the people they use become an ever-increasing scrap heap."

That scrap heap is something Robert Wyatt views from a greater distance than one would think from the regularity with which his name crops up in musical circles ("I don't really know many of the people I might seem to be in touch with" is how he puts it to me). Mostly, he says, it's because his priorities lie elsewhere - so when he goes out "It's often not to a musical event – I tend to go to things where no one knows what I do, whether they're musicians or not."

All around our limited number of figures like Robert Wyatt, individualism is presently going down – degenerating into an anarchy of instincts, a trivial welter of self-absorptions, a pathetic inability to reject those things which spell danger to real values. Yet Robert Wyatt has chosen this same moment to perfect the loneliest art – fighting every loss on behalf of life – and he's re-heard every tune he loves as a rallying cry to the collective spirit. Even, he says, jazz:

"Yes. Now I see it as much more related to other folk instrumental things. That any community anywhere can develop their own such dialect – and within it of course each individual has their own things to say.

"Jazz has made many things clear to me which have allowed me to learn from the music to which I now listen – the music which comes from all over the world."

Cynthia Rose

|