| |

|

|

An Austr-Alien in Paris - Shindig! - Issue 127 - May 2022 An Austr-Alien in Paris - Shindig! - Issue 127 - May 2022

oft Machine arrived in France at the beginning of July 1967 with a booking to play all summer long at

a “psychedelic discotheque” near St Tropez. When “all summer long” became “for three nights only”,

the band found themselves stranded in paradise with a truck full of gear and no money. However, a

chance beach-side encounter with a Parisian antique dealer would quickly turn things around. Bob

Benamou, who would soon become Gong’s manager, tells Shindig! “They were playing on the beach at a beer

festival; it was a horrible place and nobody was there. I said, ‘You can’t stay here,’ so I installed the whole

group in a villa in St Tropez. We became very close. Daevid Allen was so creative, so poetic, and so surrealistic:

an amazing person.”

Benamou was organising a series of

happenings with underground artist Jean-

Jacques Lebel. Lebel offered Soft Machine

the opportunity to perform during a

staging of Picasso’s play Desire Caught By

The Tail. The band leapt at the chance,

immersing themselves in the Dadaist

production for three weeks. Lebel told

writer Aymeric Leroy, “Daevid said to me

several times afterwards, and Kevin [Ayers]

too, that this experience had really allowed

them to ‘bloom’ as artists, to differentiate

themselves from what was around them.”

Soft Machine also scored an invitation

to play at a party organised by the owner

of Barclay Records, where they impressed

a large crowd of movers-and-shakers with

a 40-minute rendition of ‘We Did It

Again’. These performances created a buzz

among the Parisian artistic elite who’d

flocked to the Côte d’Azur that summer,

which gave the band a real foothold in

France. They would consolidate this

position by returning to the country every

month for the remainder of 1967.

|

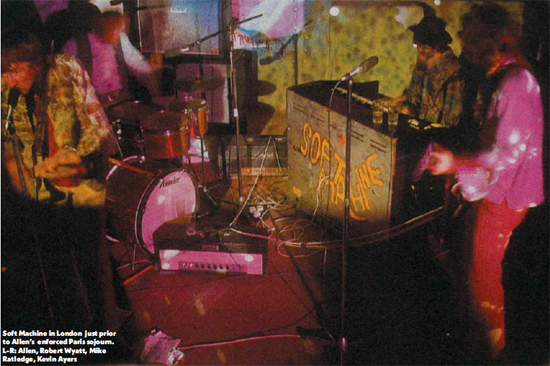

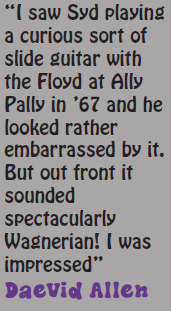

Soft Machine in London just prior to Allen's enforced Paris sojourn.

L-R: Allen, Robert Wyatt, Mike Ratledge, Kevin Ayer

|

However, Soft Machine would make

these trips as a three-piece. An expired

visa saw Allen turned back at Dover, and

even worse, banned from entering the UK

for three years. Not wanting to return to

Australia, he had little choice but to install

himself in Paris. His time in Soft Machine

was brutally cut short.

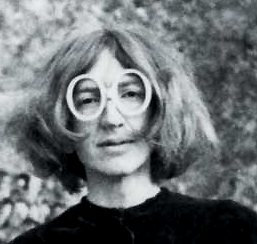

Once in Paris, Allen leapt into action,

quickly gathering a collective of

improvising musicians around himself.

These included his long-term collaborator

and partner Gilli Smyth, vocalist Ziska

Baum and flautist Loren Standlee. For

their first show they took the name Gong

Full Moon Fantastickal, and soon landed a

10-week residency at underground hotspot

La Vieille Grille. Their sets of freely

improvised music caused a sensation in

Paris’s nascent underground scene. A long

segment filmed for French TV in early ’68

(available on YouTube) is revelatory,

showing the genesis of the idiosyncratic

styles that Allen and Smyth would later

perfect in Gong.

Allen has always given Syd Barrett

credit for inspiring his “glissando” guitar

technique. In Gong Dreaming 1 he writes:

“I saw Syd playing a curious sort of slide

guitar with the Floyd at Ally Pally in ’67

and he looked rather embarrassed by it.

But out front it sounded spectacularly

Wagnerian! I was impressed.” Armed with

a box of antique gynaecological

instruments and a delay unit, Allen

learned to coax a galaxy of sound from his

Telecaster guitar. While Allen was able to

explain the origin of his style, he was at a

loss when it came to describing Smyth’s “space whisper” vocals. “It didn’t come

from any outside influence that I know of.

She just immediately began to sing like

that... Ziska Baum and Gilli were magical

together. The two of them just created

that style together out of thin air.”

Allen made many contacts at the Vieille

Grille, the most important being with the

young filmmaker Jérôme Laperrousaz. His

support would prove incredibly important

to Allen over the next few years. When

Allen told him he was looking to put

together a new group to play more

traditionally structured songs, the

filmmaker put him in touch with Marc

Blanc and Patrick Fontaine. They were

the rhythm section of a band whose

guitarist had just been called up for

national service, and as fate would have it

were already ardent fans of Soft Machine.

The trio clicked immediately, playing

their first gig together in January ’68.

Blanc told Shindig!, “We had just enough

time to rehearse two tracks [‘Why Are We

Sleeping’ and ‘We Did It Again’]. We

played three sets that were basically freakouts.

The audience was stunned, enjoying

it without realising it was Soft Machine’s

guitarist playing.” Allen christened the

new band Bananamoon. While it would

only play a score of gigs and record a

handful of demos that were unreleased until decades later, its impact on French

music would be enormous. It spawned the

bands Gong and Ame Son, and in

bringing the first flush of real psychedelia

to France, helped shape the country’s

emerging musical underground.

Laperrousaz worked on the TV

programme Bouton Rouge, and used his

influence to organise a spot for

Bananamoon. Arrangements were made

to meet in the Latin Quarter to shoot a

clip for their version of ‘Why Are We

Sleeping?’. The chosen day turned out to

be during the worst street fighting of the

May ’68 protests. The band arrived in

what looked like a war zone: hastily

erected barricades, burned-out vehicles,

and uprooted trees everywhere, and the

air electric with tension. Bravely or

foolishly, Laperrousaz leapt at the chance

to use this as his backdrop. “We were

filmed climbing the barricades with our

instruments, against a background of total

chaos”, recalls Fontaine. Filming

continued for the entire day, with

Laperrousaz truly pushing his luck at

times. Allen relates in Gong Dreaming 1 that with cameras in tow, “l wandered

down a block to find a menacing black

battle-truck full of super tough paracommandos.

From somewhere Jérôme

miraculously conjured up a large paper

bag full of toy teddy bears. So l danced up

to the wagon, and bowed to the stonefaced

paratroopers... ‘Les compliments de

Winnie le Pooh...’ l cried solemnly and

handed each of them a wee teddy bear.

Stern jawlines cracked open with

amazement and then delight. They’d all

abruptly turned into little boys. l left

behind a truckload of human laughter...”

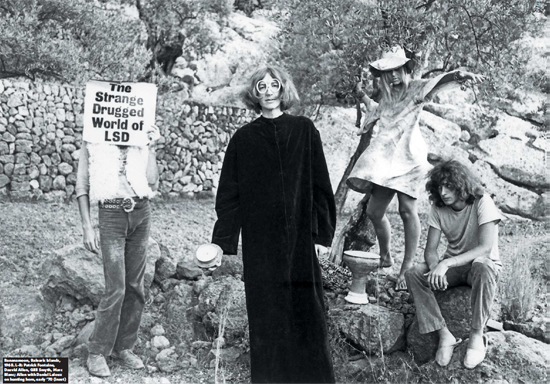

The paras may have been left laughing,

but once news of this filmed escapade

reached the authorities, they were not

amused. Laperrousaz was dismissed from

his job, but worse potentially lay in store

for Allen. Informed that he was on an

arrest list of undesirable aliens, he and

Smyth fled France. They headed for Deya

on the island of Mallorca, with Blanc and

Fontaine following soon after. Fontaine

remembers these months spent together

on their island refuge as an extraordinary

time. Living in community, they grew

closer both personally and musically.

In their absence Laperrousaz worked to

gain the interest of several record labels,

and in December ’68 Bananamoon

clandestinely returned to Paris to record

demo tapes, which ultimately failed to

secure a signing. To evade the attention of

the Paris police, the band relocated to a

property owned by Bob Benamou in the

tiny town of Montaulieu, near Avignon –

a place that would also be significant in

Gong’s story. There Allen began writing

the songs that would form the core of his

Magick Brother album.

Unfortunately, Marc Blanc was finding

less inspiration in Allen’s new music.

When Blanc’s former guitarist returned

from the army in April ’69, it didn’t take

long for him to float the idea of starting a new band. Two months later Blanc and

Fontaine split amicably with Allen to

form Ame Son.

From this point things moved very

quickly. Within months both Ame Son

and Daevid Allen had signed to BYG

Records, recorded their debut albums, and

shared the stage at the legendary

Amougies Festival. Well before

Bananamoon split, Allen had nurtured the

vision of a different kind of band. Central

to his plan was a flute and sax player he

had encountered in Paris, and then, in a

bizarre twist of fate, met again in Deya

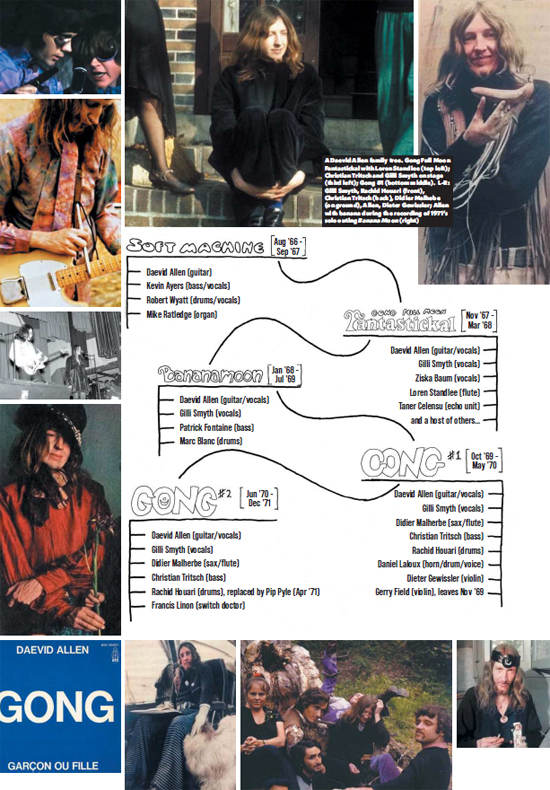

just weeks later. Didier Malherbe told Shindig!, “I went to spend the summer in

Deya and Daevid was there! Summer of

’68 was pretty amazing, one of the best

times I’ve had in my life. We were seeing a

lot of each other and playing music, and

eventually we kind of decided to set up

Gong… not immediately, it came little by

little.”

|

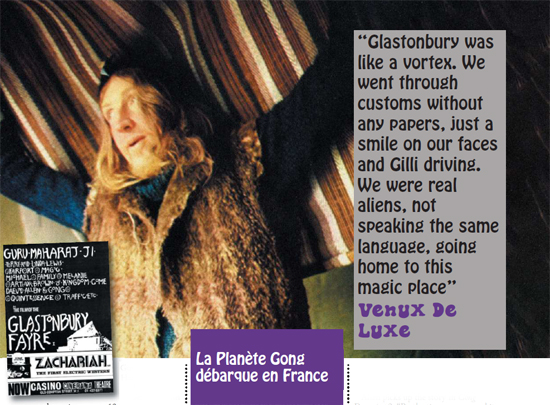

Bananamoon, Balearic Islands, 1968. L-R: Patrick Fontaine, Daevid Allen, Gilli Smyth, Marc Blanc. |

With an album to record for BYG,

Allen called on Malherbe, who would be

the one constant musician at his side for

the next five years. According to Bob

Benamou, “After Daevid, Didier

Malherbe was the most important person

in Gong: a great, great musician.”

Malherbe makes the point that Magick

Brother, recorded in September ’69, isn’t a

Gong record, but a Daevid Allen solo

album with guest musicians: himself, Gilli

Smyth, and drummer Rachid Houari –

who would all become members of Gong

– along with a number of American

jazzmen. The LP is a fine set of

psychedelic pop songs leavened with

flourishes of free-jazz. Most significant in

foreshadowing the sound of Gong-tocome

are the bookending tracks. ‘Mystic

Sister’ points towards the glissando

guitar/space whisper vocal passages of classic Gong, while ‘Cos You Got Green

Hair’ is a more earthy taster of the

floating stoned-ambient interludes of the

Radio Gnome Invisible trilogy.

Immediately after completing the

recording, the group was augmented with

bassist Christian Tritsch, violinists Gerry

Field and Dieter Gewissler, and the

wildcard figure of Daniel Laloux on

vocals, hunting horn, and marching drum.

This was the line-up that played at The

Amougies Festival in October ’69.

Because of Allen’s relationship with

BYG, the band had a feature slot at the

festival, headlining the Sunday night lineup

of French bands. However, a series of

delays and over-runs pushed their

appearance into the wee hours of Monday

morning. Gerry Field, who left the band

immediately after the festival, informs Shindig! they were billed as The Daevid

Allen Group, and he can’t recall the name

Gong being used during his tenure.

Malherbe relates that it was 5am when

they finally took the stage, and shock

tactics were needed to energise the fading

audience. “People were lying like corpses,

half asleep. Daniel Laloux was playing a

military drum from the Napoleonic

period. So Daniel pounded on his drum,

and recited a famous Victor Hugo poem

about Napoleon and Waterloo,which was

only a couple of kilometres from

Amougies.” The crowd responded

enthusiastically. The remainder of the set

featured songs from Magick Brother interspersed with a good deal of free

improvisation. In his review for Rock &

Folk Paul Alessandrini called it an

“indisputable success”, impressed by the

band’s perfect balance of “musical

delirium” and “devastating humour”.

Jérôme Laperrousaz had filmed the

festival, but the sound recording of Allen

and co’s performance proved unusable. To

recreate their music for the film, he

invited Gong (as they were now known)

to move into his family’s chateau in

Normandy. The band would stay there

for the next five months, rehearsing and

recording. The tapes from the “haunted

chateau” reveal Gong’s progression from a

psychedelic pop sound to a much harder

psych-rock featuring long passages of free

improvisation. By the time Magick Brother was released in March ’70, Gong’s music

had progressed far beyond it. In fact,

Allen is surprisingly dismissive of the

album in an early interview. “It doesn’t

represent the current group. It was a kind

of masturbation, or rather the result of

massive constipation. In short I relieved

myself.”

Only a month later Gong’s new sound

was revealed on the single ‘Garçon Ou

Fille’ which exhibited a new-found

aggression: an almost punk energy

courtesy of Allen’s fuzzed-out guitar and

violently delirious vocal. This was just

one side of the coin, though. The more

esoteric, improvisational aspect of the

band can be heard in a performance of

‘Dreaming It’ filmed at about the same time (and available on YouTube) which

brings Malherbe’s and Gewissler’s

contributions to the fore.

Surveying the band’s evolution for Rock

& Folk in ’71, Paul Alessandrini was

clearly biased towards this era’s divergent

but oddly cohesive melange of music. He

described it as “sonic madness, a kind of

violence, with so many original

components asserted to excess, without

any search for formal perfection”.

Alessandrini singled out Daniel Laloux,

praising his contribution to Gong’s

“comedic and derisive theatrical side”.

This first era would be closed when

Laloux and Gewissler both departed in

May ’70. Bob Benamou also highlighted

Laloux’s early contribution. “He didn’t stay

long, less than a year, but he was great,

completely surrealistic, a fantastic artist.”

Benamou had been installed as Gong’s

manager a few months earlier and offered

his property in Montaulieu as the band’s

home base for the summer. Before heading

there Gong spent two months in Paris,

rehearsing in the cellar below Benamou’s

antique shop.

The catalyst needed to accelerate Gong’s

development was discovered

just before they left Paris, in

the person of Francis Linon,

aka Venux De Luxe. Linon

admits to Shindig! that he

blagged his way into the

band. “Daevid told me they

were on their way to the

south and that he needed

people to help with the

equipment. Without any

knowledge at all on what

was required, I said, ‘I’m

the man you’re looking

for!’ and my whole life

suddenly changed.”

A few days later, he was in Montaulieu

with the rest of the band. “It was a typical

small village at the top of a hill, where the

road ends. Bob owned practically all of it.

Behind the village, on a plateau in the

wilderness, there was an ancient

sheepfold. The electricity had just been

connected. This is where we moved in

with the equipment. It took us more than

a week just to clean up the goat droppings

covering the floor. After putting rugs all

over, we put the gear in the middle and

around the walls some mattresses

separated by stretched fabric for a little

privacy. A stove in a corner, the toilets

outside, the bathroom in the river... The

Gong community was born.”

In the three months Gong spent there,

Montaulieu became their spiritual home.

It was there that communal living became

an essential part of their lives, and it was

there that Gong’s music made a quantum

leap; when Linon massaged their sound

through his effects processors, a truly

cosmic music emerged.

With winter approaching, life in the

sheepfold was becoming harder and

harder. After a year of nomadic

wanderings, Gong needed a permanent base. They found it at Pavillon du Hay, an

abandoned hunting lodge 120 km southeast

of Paris and supposedly discovered by

Gilli Smyth randomly placing her finger

on a map. This would be their home until

they quit France for the UK three years

later.

The passage across ‘70 had been a

formative year for Gong. They had honed

their idiosyncratic music style and

developed a strong community ethos.

They entered ’71 with only one seveninch

to their name, but with the

foundations laid for an incredible creative

explosion. The first fruit was Daevid

Allen’s sophomore solo record. Keen to

capitalise on Soft Machine’s fame, BYG

wanted Allen to record with some of his

former bandmates. With the end of his

three-year ban, Allen was finally free to

travel to the UK and do just that. In

February ’71 he recorded the Banana Moon LP with Robert Wyatt guesting on vocals

and drums. Other players on the session

included violinist Gerry Field from the

Amougies band and drummer Pip Pyle.

During the sessions Allen met a young

studio engineer who was experimenting

with a new EMS synthesiser.

“I met Daevid at Marquee Studios,” Tim Blake tells Shindig! “He was having

trouble finishing Banana Moon, so I helped

out with the mixing. Daevid invited me

to go back with him to France the next

day.” Blake relocated to Pavillon du Hay,

bringing his EMS synth with him. If all

had gone according to plan, Camembert

Electrique would have had a more

electronic edge, but a change in drummers

put a spanner in the works.

Rachid Houari’s wife had never felt at

ease in the Gong community, and he

finally made the decision to leave the band

in spring ’71. Allen called in Pip Pyle

from the Banana Moon sessions to take

over. Unfortunately, he and Blake had

history. “Pip and I knew each other, but I

don’t think we liked each other very

much!” Pyle particularly hated Blake’s

synthesiser, claiming that it sounded “like

a flock of deranged psychedelic

chaffinches”. He put his foot down, saying

it was either him or Blake. Exit Tim Blake

(at least for now).

Pyle’s first few months in Gong were a

baptism of fire. Continuing its creative

streak, the band entered the Chateau

d’Herouville studio – Elton John’s

“Honky Chateau” – in May

’71 to record two albums in

quick succession.

First up was the

soundtrack to Jerôme

Laperrousaz’s film

Continental Circus. For

Allen this was an

important opportunity to

pay Laperrousaz back for

his immense support. In Gong Dreaming 2 he writes,

“We went into the studio

clean and clear. With Pip

on drums and no rehearsal

whatsoever, we completed the

soundtrack/album in a series of perfect

first takes... recorded, overdubbed and

mixed in two days. Jérôme was

delighted.”

It was Francis Linon’s first experience in

a recording studio. “Everything was done

almost live, I was operating the echo

chambers like in a concert. Everything

went very quickly and everyone was

pleased with the result. What happiness!”

Gong were back in Herouville almost

immediately, backing poet Dashiel

Hedayat on his album Obsolete. Allen was a

fan of Hedayat’s poetry and was very

happy to provide the music for his songs

and poems. The album was completed in

another whirlwind two-day session and

has gone on to be recognised as a classic of

the French underground scene. While

these albums are overshadowed by

Camembert Electrique, they are both

essential parts of Gong’s discography. The

longer tracks gave the band the chance to

stretch out, showcasing the

improvisational power they had developed

– most notably on ‘Cielo Drive/17’ from

Obsolete and ‘Blues For Findlay

(instrumental)’ from Continental Circus.

With two albums under their belt, Gong entered

Herouville

studios yet again

in June ’71. This

was the main event: a 10-day session to

record their debut album. According to

Linon, they entered the studio primed to

bring the past 12 months to a

culmination. “The recording of

Camembert Electrique was the concretisation

of everything that happened before, the

perfect way of life at Montaulieu, and

Pavillon du Hay.” In Gong Dreaming 2

Allen writes, “The band was right on its

own cutting edge so the results were

satisfying. Within 10 days we had

completed the backing tracks and most

instrumental overdubs.”

There was a two-month gap before the

mixing sessions took place in September

’71. Allen recalled listening to the final

playback. “I felt a deep sense of

completion and I was very happy. For the

moment, we had already won. I had the

feeling that this album would be around

for a long time.” Between the two sessions

Allen had led the band across the channel

to play at the ’71 Glastonbury Festival, and

for him their first gig in England was also a

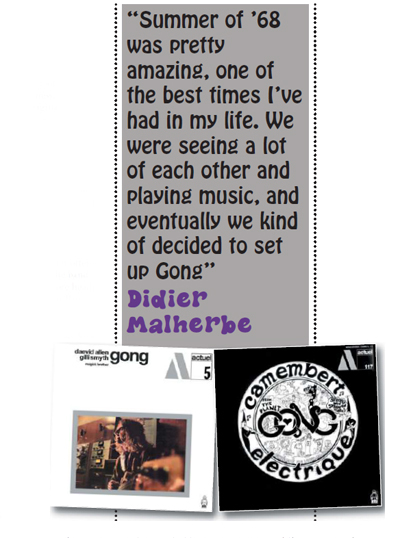

homecoming. Francis Linon’s account of

the event is striking. “Glastonbury was like

a vortex. No one could stop us doing it.

We went through customs without any

papers, just a smile on our faces and Gilli

driving. We were real aliens, not speaking

the same language, going home to this

magic place.” The band had just kicked off

their afternoon set when disaster seemed

to strike.” As soon as we started, in a climax going up, the generator broke

down.” This setback actually ended up

being a godsend.

Allen picks up the story in Gong

Dreaming 2. “By the time we resumed it

was that magic sunset time and we were

now in the glow of stage lights. We had

barely started when I looked up to see a

pied piper line of a thousand or so

dancing people snaking down the hill to

gather at the front of the stage cavorting

and rejoicing to the music of this odd

French band called Gong... This was the

kind of audience that Gong had been

created for, and the gathering awareness

of this was running both ways at once.

This was our English spiritual family.”

A certain Richard Branson was in the

audience that day, and very soon he

would be making overtures to the band.

Gong would continue to live in France for

some time, but their interplay with

England would increase. The next album

would be recorded at Virgin’s Manor

studio, and over time more English

musicians would be added to the line-up.

Gong would never lose its French

influence, but after Glastonbury it would

never be quite as strong. A new chapter

had begun.

Ian would like to thank Bob Benamou, Marc

Blanc, Patrick Fontaine, Didier Malherbe,

Gerry Field, Francis Linon, Tim Blake, and

Aymeric Leroy for their generous contributions.

Gong tour later this year and a box set is due soon.

For news visit planetgong.co.uk

|