| |

|

|

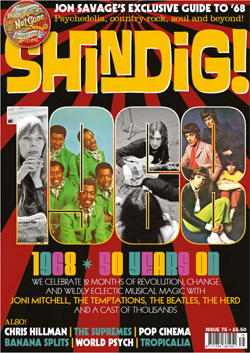

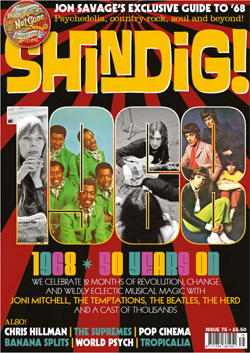

The World spins - Shindig! - Issue 75 - January 2018 The World spins - Shindig! - Issue 75 - January 2018

|

| |

The pace of social change during the '60s was too fast for some and too slow for others. Conflict was rife as teenagers all over the world enjoyed newfound freedoms just as political events surrounding The Vietnam War, Civil Rights and the threat of nuclear holocaust began to shape the music they were listening to. After 1968, rock'n'roll would never sound the same, as JOHNNIE JOHNSTONE discovers

|

|

|

|

|

n political terms, 1968 was an extraordinary year. American youth had beengalvanised by the Washington demonstration of October '67, before The Tet Offensive in the first month of the new year heightened opposition towards The Vietnam War. Civil rights protests escalated into full-scale riots in the urban ghettos following the assassination of Martin Luther King in April, and the killing of RFK in June only intensified a mood of overwhelming despair. Protest in popular music had been largely confined to folk music but bands like The Fugs and Country Joe & The Fish had already made overtly political statements on record.

But it was in '68 that rock and radicalism became inextricably intertwined. In Detroit and Ann Arbor, the rise of John Sinclair's White Panther Party was soundtracked by The MC5, and African-American music would change beyond recognition, becoming infused with righteous indignation and a growing pride in black consciousness. The era of Soul Power had arrived. That radicalism wasn't simply the preserve of American youth. In Europe too the barricades were shaking, and music had a part to play in events winch saw huge anti-war demonstrations in London and wliich would bring France and Czechoslovakia to the brink of revolution.

If, during the '60s, London (via Liverpool) had become the epicentre of the music and fashion world, Britain was still by and large a fairly conservative country and the counterculture rarely provided any substantial threat to the establishment. Young people may have joined marches but the records they bought gave little encouragement to their subversive dreams. They seemed more content to take pills and dance 'til the early hours of the morning. When Lennon sang about 'Revolution' and the Stones of "fighting in the street", the sentiments were not only non-combative but unmistakably sardonic.

But on the continent things were different. In West Germany, '68 proved to be year zero for rock music, with the birth of krautrock. This was partly fuelled by German teens' rejection of the values of their forefathers. Their country had an unspeakable past, so much so that more often than riot, German bands opted to articulate their feelings without using words at all. What could one say? The touch paper was lit by the killing of West Berlin student Benno Olmesorg by a police officer, triggering the '68 protests, and after The Essen Rock Festival that year trie musical revolution would follow.

Meanwhile in France, the political situation had reached boiling point. France was a unique proposition. There was — particularly amongst more radical elements — an uneasy relationship with rock 'n' roll and consumerism.

|

|

Sure, teenagers bought Beatles records like anyone else, but rock music was often considered symptomatic of the problem rather than the antidote to it. The writings of Sartre and de Beauvoir were de rigeur, and the French ideology of high culture contributed to a uniquely anti-American mindset, so that cultural protest was more likely to be found in university, cafes and street theatre than at rock concerts.

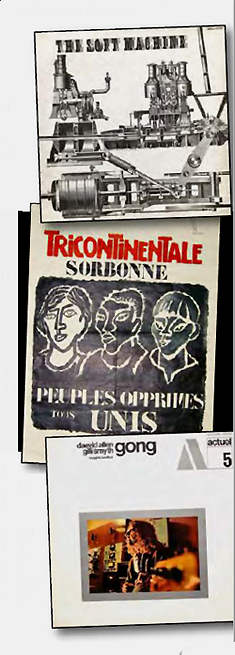

The French pop charts were a peculiar mix of traditional chansons, easy listening and pop, with the odd aberration. For instance Greek band Aphrodite's Child enjoyed a 14-week stint at the top of the charts with the mildly baroque 'Rain And Tears', 10 weeks longer than 'Hey Jude' managed, but at the moment the shit hit the fan in May, almost surreally it was Tom Jones' 'Delilah' at the summit. In many ways rock and radicalism were separate entities in France, but one British rock band would manage to penetrate the cultural barriers, to find themselves caught up in the May events: Soft Machine.

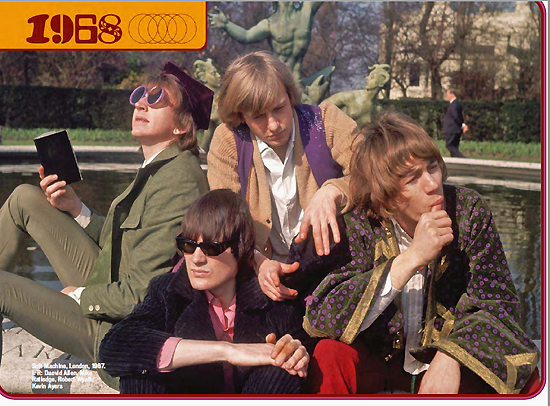

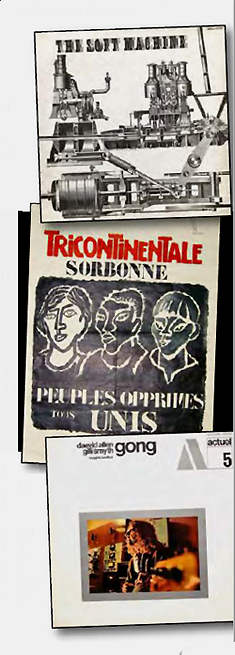

Before Aussie-born Daevid Allen arrived in the UK, he had spent time in Paris nurturing a love for the jazz lie heard there in the city's cafes. It would be to Paris he would return after forming Soft Machine with fellow jazz lover Robert Wyatt, Canterbury scenester Mike Ratledge and Kevin Ayers, whom he had first encountered in Ibiza. Ayers' more commercial sensibilities counterbalanced the more experimental avant-garde dimension to the band's sound, concocting a perfect potpourri for goatee-scratching French students. The Ayers-penned 'Love Makes Sweet Music' was one of the first British psychedelic releases (February '67) and Soft Machine toured Europe soon after, performing trance-inducing 40-minute renditions of 'We Did It Again' in St Tropez and the capital, thus making them darlings of the Parisian hipsters. Upon their return to the UK, Daevid Allen was refused entry to the country and returned to France where lie formed Gong with his partner Gilli Smyth, a poet and teacher at Sorbonne University.

While Soft Machine toured the States in early '68 supporting The Jimi Hendrix Experience, Allen was in Paris and shortly afterwards the student demonstrations at the Sorbonne began to ignite. Strikes had brought the economy to a virtual standstill and as the events unfolded on television screens across the globe, Allen instinctively was drawn to the heart of the action. "I got caught up in the '68 riots but when I turned up on the barricades to confront the armed paratroopers with a teddy bear, I managed to anger both sides — the paras and the humourless left-wing students," he told Aidan Smith in 2009.

Allen was ridiculed as "a beatnik" and decanted to Majorca for a time before eventually returning to Paris where he would work on Gong's debut album Magick Brother in '69. His former band-mates had beaten him to the punch with their own landmark debut, made without their founding member, and released in October '68. Soft Machine returned to play Paris after the threat of revolution had subsided, but if the political aspirations of French youth had been quashed, the country was in the midst of huge social upheaval, which transformed attitudes towards rock music. By the end of '68, France's most celebrated cinematographer and auteur Jean-Luc Godard had filmed One Plus One, a film featuring images of The Rolling Stones recording 'Sympathy For The Devil' juxtaposed with footage of The Black Panther Party's military manoeuvres. By '69, the French musical landscape had been transformed by the events of '68 and the influence of Soft Machine and Gong was not hard to discern in the new progressive sounds of Magma and Ange. The Western influence had been be insidious but France's social revolution softened attitudes and the music would win out in the end. The revolution would not be televised, so what could a poor boy do, 'cept sing in a rock 'n' roll band?

|