| |

|

|

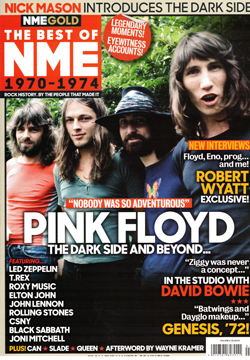

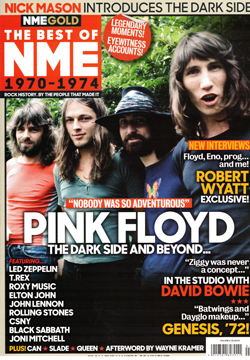

"It's a Magical Thing" - The Best of NME 1970-1974 - August 2018 "It's a Magical Thing" - The Best of NME 1970-1974 - August 2018

|

|

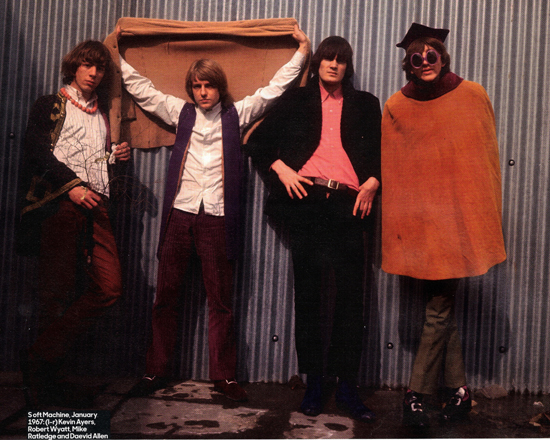

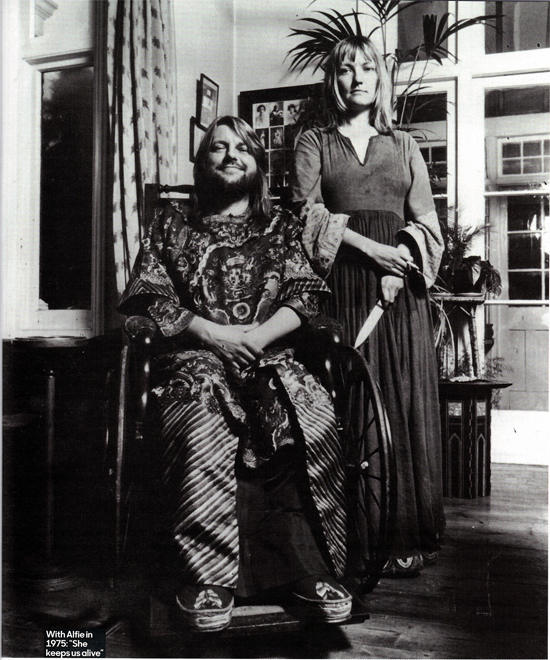

IT'S fair to say that Robert Wyatt had an eventful time between 1970 and 1974. "I got chucked out of a band," he says today, down the phone from his home. "I formed another. I fell out of a window. I spent seven months in hospital. I turned into a singer-songwriter. I played at the Proms, and I appeared on Top of The Pops. Oh, and more importantly, I met Alfie [Wyatt's partner, artist Alfreda Benge], and we're still together."

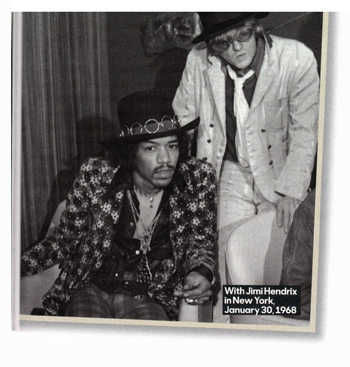

His orbit included key figures of the period - from Hendrix to Mike Oldfield, from Phil Manzanera to Eno, from Pink Floyd to Henry Cow. "Some of these friends ended up phenomenally successful," he says. "But none of them feel famous when you're in their company. It's all quite random, how you end up knowing these people."

Wyatt's life was changed forever on June 1, 1973 when, at a party for Gong's Gilli Smyth and "Lady" June Campbell Fraser in Maida Vale, he fell from a fourth-floor window while heavily drunk. He's still not entirely sure if it was an accident or a suicide attempt, but it's something that he remains incredibly positive about. "Alfie says I've coped with it by being in denial," he says. "It's been a successful strategy."

Friends rallied around. Pink Floyd played a benefit for him, John Peel asked listeners to send regards, the model Jean Shrimpton gave Robert and Alfie a car. The actress Julie Christie bought them a house in Twickenham, which they lived in for more than 15 years.

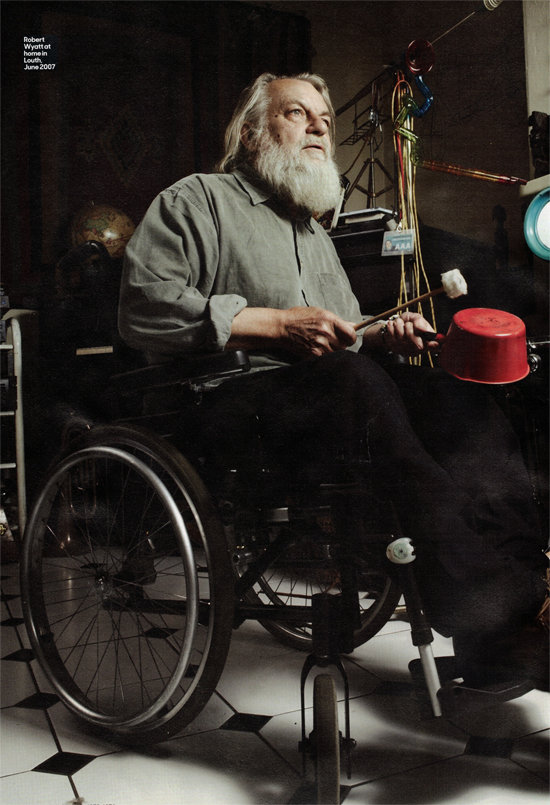

Today he and Alfie live in Louth, Lincolnshire. After an Indian summer to his career - including the Mercury-nominated album Cuckooland in 2007 - he announced his retirement from music in 2014. "Me and Alfie bumble around town. We watch telly together. It's all very civilised."

How the devil are you?

Well, the correct answer to that question should always be "I'm absolutely fine, thank you". The actual answer is that we tend to fall apart in our seventies, and I've made things more difficult for myself by breaking my back 40 years ago, ha ha. And I've had to consider that, for all the benefits of breaking my back, there are drawbacks that I hadn't anticipated. But I'm fine, I'm well looked after and well fed, and Alfie's just made me some fantastic fish paste, so what more can I ask for?

The period between 1970 and 1974 was a pretty eventful and turbulent one for you..

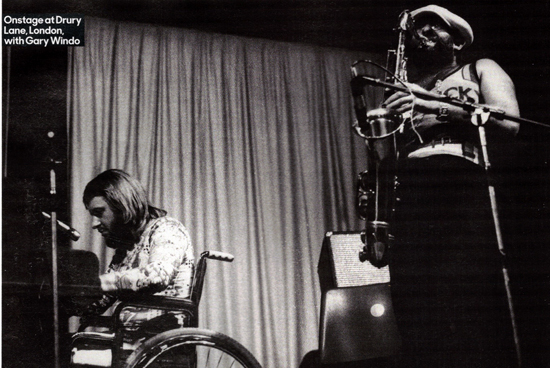

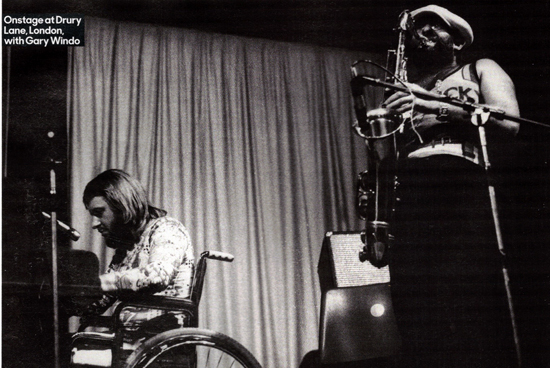

Yes. For me, it ends happily with the Drury Lane concert in September 1974. This was a fundraiser for me, after my accident, and it does sum up the story so far for me in a very happy way, so I have a great nostalgia and affection for it. Because of the occasion it very vividly conjures up all the people I worked with during that period. The introduction is by John Peel, and there's all these wonderful musicians working on it - Nick Mason from Pink Floyd and Laurie Allan on drums, Mike Oldfield and Fred Frith on guitars, Dave Stewart on keyboards, Ivor Cutler, the trumpeter Mongezi Feza and the saxophonist Gary Windo. It's a great window into a whole musical scene at that point in the 1970s, and snapshot of my life. I didn't really do live gigs after that, so there is the nostalgia of that too.

How did that gig come about?

Luckily, other people did all the work for me. A key figure on that project was Dave Stewart, from National Health and other bands. He is absolutely brilliant at scoring things for people who couldn't write music, for publishers. He went through Rock Bottom and arranged the entire thing. We played the album, in its entirety, then added some other bits and pieces to make it a full, proper-length concert. It was a frighteningly good bunch of musicians. What I liked about it was, if you form a group, it becomes a thing, an entity. Whereas, doing a one-off thing like that, it's a bit like making a film. So we'd have Laurie Allan on drums for one thing, Nick Mason on drums for another, or Mike Oldfield and Fred Frith sharing the guitars. We had that variety of noises available.

You go back a long way with Pink Floyd...

Oh yes. We didn't really tour with them, but we shared the bill with them in lots of London gigs in the early days, and then they took off, quite rightly, with two great pop singles - "See Emily Play" and "Arnold Layne" - and entered a different league. Soft Machine bashed around, we got gigs, but it was on a different scale. Occasionally on the continent we'd be put together on bills. But we were so different that we weren't at all competitive, because there was no rivalry. We got along exceptionally well. We had little in common, musically, but I know that Kevin Ayers and Daevid Allen were both very influenced by Syd Barrett, his guitar approach, that slide guitar thing. And I was very much inspired by Pink Floyd's lovely organ player, Richard Wright. He really knew how to play organ in a way that you're not trying to do Jimmy Smith, you're just playing a wash, creating an atmosphere that enhances an instrumental. I

thought he was absolutely brilliant at that, and I credit him for that unobtrusive but utterly essential role he had in the band. And Nick [Mason] is a wonderful, funnyman, and a terrific producer.

I'm biased in favour of Floyd, because I get on so well with them, and they've been lovely to me. When I had my accident, I think they found out about it through a mutual friend, David Gale, a friend of Alfie's, I think it was Roger Waters who said, we must do a charity concert for Robert and Alfie. Alfie and I didn't have any money at the time. So it was a fantastically helpful thing for them to do. It took away the panic from coming out of hospital and so on. I always liked Floyd. They were great people, funny, generous, and they always make stunning records.

Prog rock was becoming massive around the first half of the 1970s. What did "prog" mean to you initially?

The first time I heard the term "prog rock", I assumed it was short for "programmatic rock", ha ha. In the way that classical music purists believe that rot started in the 19th century when composers in Russia, England, Spain, France, Brazil, and so on started weaving folk songs and narrative themes into their music, and called it "programme music". I thought that was quite wonderful, but a lot of people were very snobbish about it. So the first time I heard the phrase "prog rock" was when Soft Machine came back to England having been in the States for all of 1968. I thought, 'Oh that's nice, music that refers to other things and weaves narrative themes into music.' I was baffled to discover it was used to describe bands like us! It was like when I heard about a "Canterbury scene". I thought, 'Oh, that's nice, I'd like to hear some of these bands who come from up the road.' I later discovered that it meant us! Prog started to develop all these weird connotations - references to Arthurian legend, pig Latin names, all that business. And, as Paul Weller might say, "I'm not having that!" So, for me, it was back to writing about cups of tea and real things, however trivial and silly. I've been a bit nasty about prog rock in the past, but I should stress that every

one I met in that world was absolutely lovely. It was just a different world from mine.

There was a lot of overlap between your work with Soft Machine and End Of An Ear and the jazz-rock of bands like Lifetime and Return To Forever. What did you think of that?

I can see why people would say that but, to be honest, I don't even like jazz rock, not very much. That self-conscious jazz thing of, ooh, let's grow our hair, get some electric guitars, give ourselves a name with mystical, cosmic connotations rather than being the Fred Bloggs Quintet. I found it very embarrassing, the jazz musicians were trying to get in on this scene, thinking, 'Oh, it's not fair, we can play better than these rock musicians.' They always reminded me of the police in disguise at rock festivals, looking out for druggy people to arrest. The long hair was a bit too coiffed, the moustaches a bit too neatly clipped, the shoes a giveaway, the flares just a bit out of date. They always stood out a mile.

You've always had an interest in the song...

Much as I love free improv and all that stuff, song and dance is absolutely the basis of music. There's a quote from Charles Mingus that the further music gets from song and dance, the further it gets from really mattering in some way. Obviously, I love listening to every kind of experimental music, in the classical world, in the jazz world, in the avant garde world, rock'n'roll, pure noise, all of that, and it's all very exciting. But, to me, music is based in some kind of social function, and that's song and dance. I think it was Stravinsky who said that the song is the one thing in music for which there is no other equivalent in any other artform. So, compositional structure you can compare with architecture, for example, and you can compare timbral effects with, say, brushstrokes in painting. And so on. But the thing that makes a tune a tune - there is no equivalent, it's a magical thing. If you can hold one down and capture it long enough to put it on record, that's a wonderful thing.

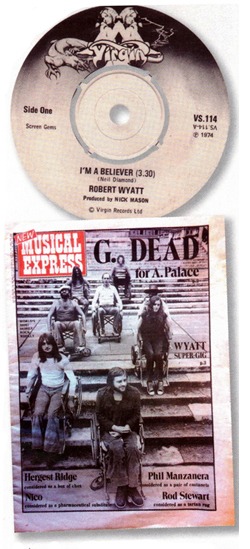

Is that what inspired your version of "I'm a Believer"?

Part of the decision to record that was sociological mischief. I've always said that the only difference between pop and rock was that pop was for girls and they changed the name to rock for boys. It's like calling perfume "after shave"! I didn't like the emergence of a kind of class hierarchy of genre in music. I hated it in the old days, when classical critics would say that jazz isn't proper music, blah blah blah. I've never believed that any idiom is any intrinsically superior or inferior to any other. It's like a really good fried-egg sandwich can be much better than the worst posh French meal.

So, with "I'm A Believer", not only is it a Monkees tune - it's by Neil Diamond. Very good entertainer, catchy songs, but had no status at all outside that world. At the same time, I liked the chords I heard on jazz records, so I thought it would be fun if the pianist Dave MacRae played the kind of chords that McCoy Tyner might play. He's a very classy musician, he played with Sarah Vaughan, for fuck's sake!

At the start of the 1970s, you were living in a house in Hampstead with some interesting characters...

Yes. The singer-songwriter Linda Lewis was one of them, God bless her. She had an electric piano, and would sit there like a little bird, singing away, which was lovely. The flat actually belonged to Ian "Sammy" Samwell, who wrote "Whatcha Gonna Do About It" for the Small Faces, among many other songs. There was a lovely young American women, very unkindly called Toad - I don't know why so many lovely women get these ridiculous nicknames, like John Peel's Pig. There was Jeff Dexter, the quintessential underground DJ. And there was also the artist and writer Caroline Coon - her thing at the time was running Release, a legal organisation supporting people who were doing drugs and being harassed by the police. She, of course, inspired the Matching Mole song "0 Caroline", but it was also about other things. It was a fascinating environment, but a dark time for me.

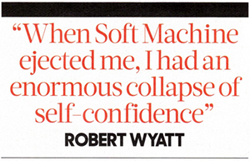

This was around the time you got kicked out of Soft Machine?

Yes. I was very, very unhappy. I mean, it had to happen, but I had taken the Soft Machine for granted as a little family. It had formed from friendships that dated back to infancy, from 10 or 11 years old. You can fall out with your family, but you can't divorce them. So, when Soft Machine ejected me from that family, I had the most enormous collapse in self-confidence from which I've never really recovered, to be honest. And I always think they were right, looking back on it, to throw me out. I was too drunk, they were more grown up, more sophisticated, everything. But nevertheless, it felt like being exiled from a country, to somewhere where nobody spoke your language. I was very disorientated, and nervous, and anxious. I had been a rotten dad - my son had been born in 1966 and I wasn't being a proper dad to him, so in many ways it was a good thing when Pip Pyle took over my role in the family when he moved in with my ex-wife, Pamela. So it was a dark time, but I was very grateful to have a place to stay, and immensely grateful to the people in that house who put up with me and helped me get through it.

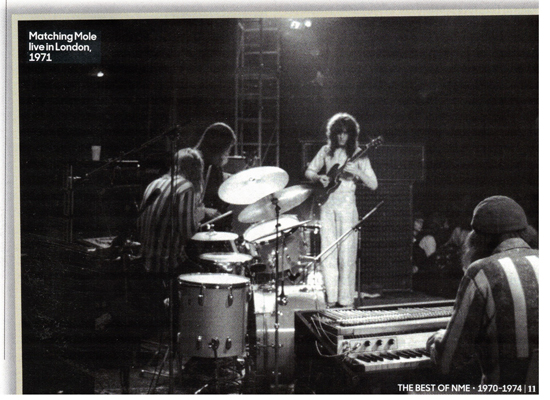

With Matching Mole, did you find it difficult to run a band?

Well, I found out that I can't be told what to do, which is what annoyed Soft Machine, but at the same time I can't tell other people what to do! I'd end up telling people to do what they like, which is ridiculous, really. The thing is that musicians always need direction. As it happened, I was lucky to be working with such great musicians - Bill MacCormick on bass, Dave Sinclair and then Dave MacRae on keyboards, Phil Miller on guitar - who wrote some wonderful bits and pieces. But part of the problem was that we were dead broke. Me and Alfie hadn't accumulated enough money for us to put down the deposit on somewhere to live - all that money immediately went into Matching Mole, and I never did get enough money to buy a place to live. I've been dossing ever since. I'm now dossing in my wife's house!

You also started working with Brian Eno at around this time...

Yes, I've been pondering what we have in common. With elephant herds, when an unruly and aggressive male gets ejected from a family or a herd, it's called a rogue elephant. Sometimes these rogue elephants get together. And I see me and Brian Eno as like that -a couple of rogue males, misfits from bands who didn't know what to do with them, who left those bands slightly unhappily. We got on really well, still do. What I loved about him is we have absolutely opposite tastes, musically. I don't think he likes what I do at all! For him, jazz is appallingly cluttered and filled with too many notes. But we get on well talking theoretical and discussing things. He was the perfect person to hang around with in the studio. I found him absolutely invaluable. I also used to like hanging around his place, sometimes I'd join in on

different things. He did a record called Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), on which I did bits and pieces, and then there was Another Green World. I seem to remember doing a little on that, and changing my name to that of a female Labour MP on the credits, just because I thought there should be more women involved in this music. Anyway, I'm there doing some percussion and vocal things. Brian is very underestimated as a singer. I wish he'd sing more. I've got him singing this century on a record called Cuckooland.

Rock Bottom was actually written before your accident, wasn't it?

It was. I had just started going out with Alfie. She was working on films - she'd studied filmmaking and editing and so on - and she had a modest role, working with her friend Julie Christie, who was doing a film with Nicolas Roeg in Venice, which turned out to be Don't Look Now. It was too early in our relationship to risk being apart, so I went with her, even though I never usually take holidays. She was on set all day, and I didn't have much to do, so Alfie found a little keyboard in a little Venice shop - an organ called a Riviera. I found a stop on it that just so went wonderfully with the water around me in Venice. So there I was, on the island of Guidecca, just off one of the big canals, with this rippling water dancing around me, making sounds on this Riviera organ. Once I got the sound, the songs just wrote themselves. So most of it was written before the accident. There were bits I finished while I was in hospital - the ending of "Sea Song" I wrote on a piano in the hospital - it was based on "Red Is The Colour" by Nina Simone.

What are your memories of performing "I'm A Believer" on Top Of The Pops?

I had a run-in with the producer of Top Of The Pops, Robin Nash. Anyway, he's dead and I'm not, so I won. Ha ha! He said, do you have to sit in the wheelchair? It doesn't look nice on a family programme. He wanted to put me in some wicker armchair. I told him to fuck off, and he told me I'd never work on the programme again. I should have said that I'm too posh to care. Which I am. Ha ha.

There was a similar issue when the rest of the band, before the Drury Lane concert, were photographed in wheelchairs, in solidarity with me, on the front cover of the NME. Some people thought that was tasteless. I quite liked it.

I mean, I could make more of it and become a disabled rights activist. I get into trouble with disabled groups for not being militant about disabled rights. My answer is that I can't be an everything activist! One person kindly said, well, the fact that you've done more since your accident than you did before should be encouraging enough for disabled people! It shows you that the world doesn't come to an end.

The accident did change your career: do you think it pushed you in directions you might not have explored?

Absolutely. I cannot regret it, I honestly can't. I mean, it's possible that the next incarnation of Matching Mole could have been a really great band, had we made a third album. Particularly the brilliant Francis Monkman on keyboards - he was an incredible musician, so much better than was necessary in that context, and I'm proud of what came out of our short collaboration.

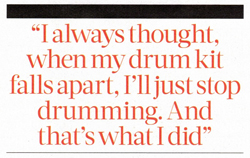

But yes, I was pushed into a new career. I'm very bad at repairing and looking after things. I always thought, as a drummer, when my drum kit falls apart, I'll just stop drumming. And that pretty much happened with my kit sometime around 1973 or '74, which was actually one that Mitch Mitchell had given me at the end of a Hendrix tour in 1968, so it had already had a bit of a battering. But, being Mitch Mitchell, it was a wonderful kit. So everything I played on after 1968 was on Mitch Mitchell's drum kit, which might interest some drum anoraks!

Did your inability to play the drums push you into singing and songwriting?

Definitely. I first got interested in songwriting while writing a long piece for Soft Machine's Third (1970), called "Moon In June", made up of lots of fragments of songs I'd written. Previous to that, on the second Soft Machine LP, Volume II (1969) I'd got lots of fragments of Hugh Hopper's pop songs, and turned them into a kind of suite on the first side of the album called "Rivmic Melodies". The one with the alphabet song and "Pataphysical Introduction" and so on. I enjoyed that so I thought I'd do that with my own songs. "Moon In June" was a revelation for me. Playing most of the songs by myself for about 10 minutes, then the others join in. Of course, being a drummer, in a band, you can't spend a lot of time playing the keyboard live. So it wasn't until I was actually physically unable to play the drums that I actually started to explore that side of things.

And I always enjoyed singing. Originally, when I started singing, I tried to be like Van Morrison, but I realised this wasn't going to happen. I'd try and sing like that wonderful singer in the Small Faces, Steve Marriott - " Whatcha Gonna DO About It"! - but I just couldn't do that mid-Atlantic thing convincingly at all. So I dropped all of that pretence and I took the risk of just singing how I talked.

What were your inspirations as a songwriter?

The trombonist Annie Whitehead once asked me where I got my tunes from. I said, I have a very good record collection! Ha ha. In each of my songs you might find fragments of, say, a Curtis Fuller solo, or a Duke Ellington tune, or something. People who don't listen to jazz won't see how disgracefully plagiaristic I am! So many jazz records are just so rich in arrangements. Listen to the way that Gil Evans arranges for Miles Davis, for instance, how he finds places to go and things to do. Listen to his arrangement of "Porgy And Bess" and hear what he gets out of the tunes when he rearranges. It is remarkable. That's how I try to make music in my head, though it rarely comes out like that.

But, as I say, if you can hold one down and capture it long enough to put it on record, that's a wonderful thing, and that can be enough. There are pop musicians who can just play well enough to accompany themselves playing their own

song, and that's absolutely fine. That's pretty much what I do.

|

| |

|

|

Have you heard that John Peel apparently had two pictures up in his kitchen - one of the Liverpool manager Bill Shankly, and one of you?

Someone told me that recently and I was quite tearful. I really loved Peel. Like Brian Eno, we didn't always agree about music, but he played tons of interesting stuff and, as people, we got on great. I do remember once that we were at his place once, and Alfie started watching an Arsenal match on telly, and he walked straight out for a walk and came back in a bit of a huff! But that's the only difficult moment with him. I got on really well with him and with his producer John Walters, a very funny man. I didn't spend as much time with them as I'd have liked - I'd always back off from getting to know people on that side of the music business. It felt a bit like payola, a bit of emotional blackmailing. I'd worry that they might feel obliged to play your record even if they don't want to. It felt unethical to me. But now he's dead I think, 'Oh fuck, why were you so silly?' But Alfie and I did used to go to visit him, we went to his wedding, and we got on great with Sheila. She's great, lovely family. And I love hearing his son on BBC6Music, sounding exactly like him.

Did you ever read the music press at the time?

I appreciate what they do. Brian Eno always says, jazz is just about faith - he reckons how much you enjoy it depends entirely upon how much you believe in it, especially with free jazz. My answer to that was always that rock is just about sociology. It's a lot to do with young men bonding, being a gang that audiences can identify with. The temperamental singer, the mad drummer, the taciturn bass player, and so on. The music weeklies were great at that sociological thing. Plus, as the editor of NME once said, there's got to be a great new band every week because there's got to be a cover each week!

What do you do with your retirement now?

Scandalously little. You know what? Any highfalutin' ideas about being an artist have been shattered. Now that I've had to give up smoking and drinking, I can't be bothered. I lived entirely on artificial stimuli. So I now just hang out with Alfie doing absolutely nothing, while she keeps us alive. But I like my little town. I go around, get a coffee, and me and Alfie we watch telly together. I loved watching the World Cup, it was fantastic. I still watch the latest comedies - whereas the music I listen to is very global and often outside the Anglo-American world, my favourite comedy is all British. I'm a big fan of Stewart Lee's TV show, which you'd probably expect. I love Would I Lie To You?, I love anything with David Mitchell and Bob Mortimer. Milton Jones is a tremendous stand-up. I love his stupid one-liners. I watch old episodes of The IT Crowd and Spaced, and the comedies with that lovely woman who co-wrote Spaced, Jessica Hynes, you know, W1A and Twenty Twelve. I always look out for new sitcoms on Channel 4 and the BBC, and check out the comedy on Radio 4.

How was playing live, with Paul Weller, last year?

I was completely caught off guard by that request. And I was completely caught off guard by how long it was since I'd done it. I was pleased to be asked. Paul's been so great. He'd be like, come on Rob, you can do Glastonbury. I certainly couldn't even consider doing that. I'm a bit like, the less I do, the less I do wrong at the moment. I've had a wheel-on part when I helped produce a Brazilian record for Monica Vasconcelos, revolutionary songs from the 1960s. So, I keep my hand in with things like that.

What music are you listening to?

I used to buy old remaindered CDs from the Woolies in Louth. Since that shut down, I've lost that physical contact! But I'm always finding interesting stuff on YouTube. I'm a bit of a Russophile and I came across an enchanting Russian choir called White Gold who just make YouTube videos on the streets and in cafes around Moscow. They use these wonderful, full-throated Slavic harmonies. A bit like that amazing Bulgarian choir, Le Mystère Des Voix Bulgares, remember them? And I like reinvestigating stuff I liked in the early '70s. There's a terrific old Soviet jazz musician called Vagif Mustafa Zadeh, an Azerbaijani pianist, his daughter Aziza is also brilliant. But Vagif, he was amazing. A very florid pianist, a bit like McCoy Tyner, he plays piano like a cimbalom. I remember hearing him on Radio Moscow in the 1970s. If I'd know he sold records here at the time I would have championed him! I've also been listening to Julia Boutros, a Lebanese Christian diva, I love that Arabic singing - the power and the passion, blimey.

|