| |

|

|

Soft Machine Man: Up from Rock Bottom - Rolling Stone No 178 - January 16, 1975 Soft Machine Man: Up from Rock Bottom - Rolling Stone No 178 - January 16, 1975

|

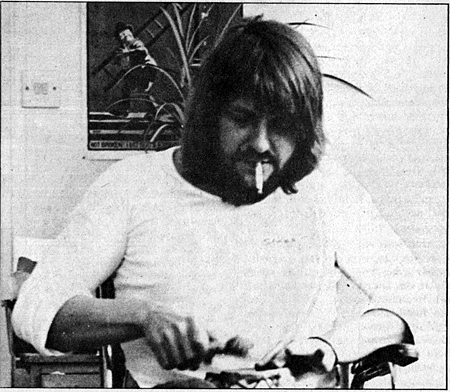

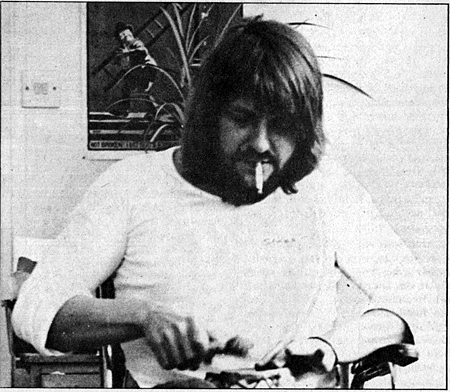

LONDON—There was something surreal about Robert Wyatt's recent appearance on Top of the Pops, BBC Television's weekly ritual enactment of the Top 20. "A ramshackle charm" was a phrase he used about something, and it seemed right for him. He stuck out like a sore thumb amid the satin and tat— the veteran from psychedelic London, now a cripple in a wheelchair, smoking incessantly and joking elliptically, the drummer's hands restless in their redundancy.

|

He was there to sing a single, his first, already a minor hit—"I'm a Believer," the Neil Diamond-penned Monkees hit. A far cry from the jazzy experimentals of the Soft Machine, though the voice is the same: frail and witty and very South London. "There are as many good pop songs as there are good jazz solos," he said. " 'I'm a Believer' just seemed to fit my throat. At 29, it was his first appearance on nationwide TV.

The rise, fall and rebirth of Robert Wyatt is a warming story. Wyatt was a drummer, vocalist and founding force of the original Soft Machine, the late-Sixties cocktail of jazzy influences ("simple riffy Mingus" is Wyatt's label), acid innovations and great British whimsy. Wyatt was celebrated for his bare-chested drum solos, his fondness for liquor and his rendition of the lines "I'm nearly five foot seven tall/I like to smoke and drink and ball."

Chas Chandler looked after the Soft Machine until "one day he came rushing in saying, 'I've just found this fucking genius who plays guitar with his teeth!' " Hendrix took the front seat, but the Softs were supporting on his 1968 U.S. tour, their first album already popular. In 1969, Wyatt made a solo album, The End of an Ear, and in 1971, after their fourth album was recorded, he split from the Soft Machine, "We just weren't friends anymore." Then he formed Matching Mole ("machine moelle" is French for . . .?). Matching Mole was preparing its third album and a tour when, in June 1973, Wyatt attempted to leave a party by climbing down the drainpipe. He fell three stories and woke up the next day with a broken spine and little chance of walking, or drumming, again. The general assumption was that he'd flown out of the window on acid. "No," he told them, "it's good old alcohol, you know — the legal one."

|

He mended his life for a year, married an artist called Alfie, and now he's back in circulation, dispensing "ramshackle charm" around the Television Centre, negotiating the python-sized studio cables with his nifty back-wheel balances. He is back with something to sing about, and his new solo album, Rock Bottom, produced by Pink Floyd's Nick Mason, is a song and a half, a plaintive voice over lush, enigmatic arrangements, the whole thing lyrical with lost movement and a childlike clearness.

Wyatt's music is unmistakable. What is more important is that his music is a focal point for a nucleus of musicians busy trading ideas, intergigging and cross referring. It's not quite a new wave yet, but it is a thoroughly ongoing eddy. Wyatt's lineup at his recent Drury Lane concert is a good example: Mike Oldfield on guitar, Dave Stewart (Hatfield and the North) on keyboards, Laurie Allen (associated with Gong) and Nick Mason (Pink Floyd) on drums, Hugh Hopper (ex-Softs) on bass, Fred Frith (Henry Cow) on guitar and Mongezi Feza on trumpet. These bands and soloists are constantly interweaving, and a distinctive tone is emerging. Interestingly, like a city sound—Mersey and Philly, Boss-town and Motown, Muscle Shoals and Ville Platte—these artists are linked by a record company, Virgin Records.

So the moment was auspicious as well as nicely surreal when the five million pairs of eyes tuned into Top of the Pops were momentarily puzzled by this bearded gentleman in a nightshirt, swaying around in his wheelchair and singing in a funny voice about how disappointment haunted all his dreams. In a career dedicated to small acts of cultural sabotage this was perhaps the coup de grâce. But Robert Wyatt maintains, of course, a healthy skepticism about pop history and its making. "I don't know why everyone worries so much whether it's a good period or a bad period for music," he says. "I'm having a great time. I never have liked these epoch-making records anyway!"

|