| |

|

|

Looking' Back - The Soft Machine Part 1 - New Musical Express - January 25, 1975 Looking' Back - The Soft Machine Part 1 - New Musical Express - January 25, 1975

|

|

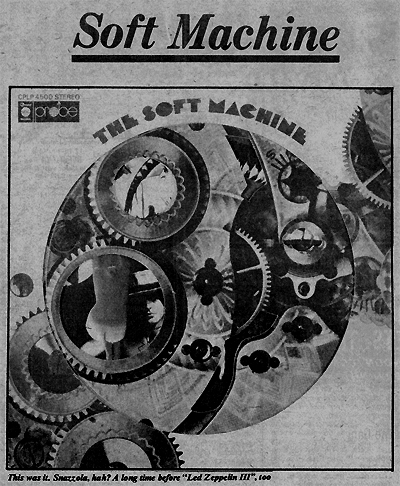

"It's a Now sound, swings like jazz, rocks like rhythm-and-blues, heavy with fuzz-box distortion, off-the-keyboard with electronic atonalities - the sound of music updated by the music of sound".

So wobbled the sleeve garf for "The Soft Machine", a rather extraordinary debut album that was somehow never available in Britain (probably because of the sleeve garf). But don't be put off by the spiel - the Softs were just about the first British group to experiment in any real sense with "progressive" music, and their impact, though low-key, was nonetheless profound and lasting.

In the first of a two-part series, IAN MacDONALD (who really GETS OFF on this stuff, kids) Looks Back on the Rich Kids who Dropped Out and Made Good.

CLASS OF'61 at the Simon Langton School, Canterbury - an exclusive, private establishment for the sons of local artists and intellectuals. Very free, emphatically geared to the uninhibited development of self-expression. A hotbed of teenage avant-garderie.

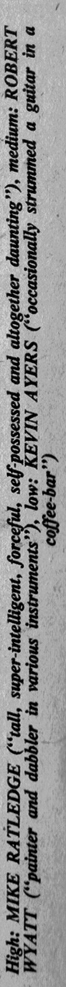

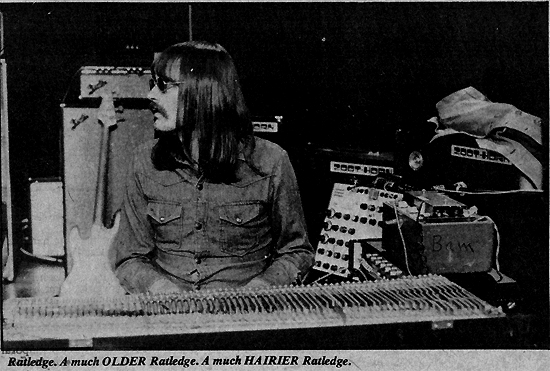

On my right - in the sixth-form and waiting impatiently to go up to Oxford to study philosophy and psychology: Mike Ratledge. Occasionally he and class-mate Brian Hopper get together to play their own adaptations of Hindemith's organ sonatas, arranged for piano and clarinet. The big boys.

On my left - two years below Mike and Brian - another Hopper. Studious Hugh, bespectacled and prematurely-balding science student. At the moment he plays a bit of sax (in emulation of his older brother) and a bit of guitar; nobody's yet suggested that bass might suit him better.

And, in the same year but in one of the arts classes: Robert Wyatt, aged 16, painter and dabbler in various instruments. He ran into Hugh back in the first year, but they went their different routes through the funfair of academe and have only recently become mates, mainly through a common interest in music.

A year below them, one David Sinclair is taking piano lessons - but he's far too young to associate with the likes of Robert and Hugh.

IT'S ALL pretty idyllic in retrospect - visiting each other's houses (but mostly congregating at the 15-room Georgian mansion owned by Robert's mother, writer and broadcaster Honor Wyatt) to play the new jazz releases - Mingus, Coleman, Taylor, Monk - and to enthuse over contemporary mainstreamers (Stockhausen, Luigi Nono), painters (Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock), and writers (Burroughs, the Beats).

However, like most people's formative years, it was hard edged under the general soft-focus.

At the point isolated above, Wyatt, unable to stand the academic strictures of school life any more, fled during his 'A'-levels and enrolled in a sculpture course at the Canterbury College of Art. When this revealed itself to be no escape either, he had a brush with suicide and before taking off to Spain, where he arrived, penniless and unable (then) to speak the language, in early '62.

Luckily, he ran into drummer George Niedorf in a club. Niedorf took him under his wing for a few months and, when Wyatt decided the time had come to re-dig Canterbury, he invited George back. (Niedorf subsequently lived for some time with the Wyatts, teaching Robert drums in lieu of rent.)

But far more significant a result of their meeting was the bringing together of the Canterbury crowd and an eccentric Australian friend of Niedorf's - Daevid Allen.

Allen, who'd left his hometown Melbourne in 1960 at the age of 21, was a walking physical embodiment of your actual day-to-day avant-garde. He knew and had worked on slides with Burroughs; in his adopted second home, Paris, he'd been experimenting with things called "Tape-loops" in the company of the then-unknown Terry Riley; but, heaviest of all, he'd taken ACID - arriving at the norm of a life-style few young people would catch up with until 1967.

He was, in fact, a fully-fledged Freak - and, as yet, The Beatles hadn't even recorded "Love Me Do."

Allen immediately invited Wyatt and Hugh Hopper over to Paris where he lived in a houseboat with his missus, poetess Gilli Smyth, at the Quai D'Orsay. Acid and mescaline were doled out to a soundtrack of Allen's own musique concrete and - pow! - two more recruits to ye olde youth-cultural revolution.

Wyatt went home with long hair; Hopper stayed on, completely fascinated by tape-loops of which he made thousands in the next few years.

Back in Canterbury, musical matters were already well under way.

The band, which changed almost daily, was called The Wilde Flowers and featured in its line-up (which extended up to 1967) the Hopper brothers, Wyatt, and all four original members of Caravan. As soon-to-be-Softs left, soon-to-be-Caravans joined - the resulting genealogy being far too complicated to go into here (for the curious, issue 28 of Zigzag features an exhaustive family-tree of the Canterbury groups compiled by Pete Frame and Al Clark - though naturally it's now a little out of date).

The Wilde Flowers' first gig took place above a pub in Whit-stable. "They try for an Indian influence," ventured a nonplussed but genially-disposed Canterbury Gazette. "Their Rolling Stones haircuts make the fans go crazy."

(The Stones had just released "Come On" at the time.)

But if it hadn't been for the international recognition-sign of Long Hair, it's doubtful whether the singer on that gig would ever have come into contact with the Canterbury mob at all.

Kevin Ayers lived in Herne Bay - only ten miles away, but hard to get to - and, though he strummed a guitar in a coffee-bar occasionally, he had no intention of pursuing a musical career until Wyatt sought him out one afternoon on the advice of a passing stranger. (Whose words were: "Oh, I thought we had the only long-hair in Kent - ours is over there in the bar if you want to check him out.")

AT FIRST, the Flowers followed well-developed Canterbury biases: a bit of jazz, a touch of rock, mostly blowing on Cannonball Adderley numbers.

Daevid Allen's arrival tipped the balance towards rock and free-form improvisation; Hopper, trained to respect repetition as a valid ingredient through his experience with loops, inveigled everyone into riffing on James Brown numbers; Dave Seeger, a rock 'n' roll singer who dropped in for a few months to have a rave, taught Hugh the bass-lines to the collected works of Chuck Berry and Little Richard.

It took a long time for the elitist hangover from Simon Langton to dissipate sufficiently for the others to condescend to trying out some of Kevin's songs. But - just as Ayers and Allen, collaborating on material, were about to swing the thing round to out-and-out rock 'n' roll - a letter arrived from Oxford.

Mike Ratledge, it said, was bored with university; he wanted to blow some.

This played right into the hands of Hugh, Brian, and Robert, who - studying the contemporary scene in London - had decided that all-guitar front-lines like the Stones and The Yardbirds were definitely passe; the thing, they reckoned, was to get into a kind of Mose Allison/Georgie Fame/Graham Bond bag. Organs and saxes. Jazz-blues.

Yikes!

Ratledge arrived just as the Hoppers left to do Other Things (Hugh to join Pye Hastings and Richard Coughlan in the next version of The Wilde Flowers; Brian to go into insurance), and his impact was hefty. He was tall, super-intelligent, forceful, self-possessed, and altogether daunting.

And he wasn't impressed with Ayers' songs.

Nevertheless, the new regime settled down to rehearse with an appropriate new seriousness and the music that emerged sounded about as much like Graham Bond or The Yardbirds as Reginald Dixon sounds like Larry Young.

They began to play gigs more professionally, began to hire themselves out for parties — gaining the first elements of A Reputation.

At this time the name of the band was changing almost by the hour. The Bishops of Canterbury was the handle they were using the night I first saw them in '66; Ayers' preference was Mr. Head. Allen preferred Dingo Virgin and the Foreskins (or Four Skins, as when a bloke called Larry Nolan temporarily raised the roll-call to five by joining briefly on guitar towards the end of the year).

|

One day Ratledge decided on the final choice.

(Though legend tells of a close finish with another Burroughs book, "Nova Express". Either way, Allen phoned Burroughs to ask his permission and got it, along with the novelist's blessings.)

Now all they needed was the wherewithal to move to London and Get With The Scene, Daddy.

The problem was solved by two occurrences.

First, Wyatt's mother sold the mansion and moved to Dulwich where she was able to rent out cheap rooms to most of the band. Second, Allen and Ayers - holidaying in Majorca as usual - ran into a spaced-out American millionaire called Wes Brunson who, convinced they must be the next Beatles, forthwith sold his shades factory in Tulsa and generously financed the group out of the proceeds.

(He later freaked out and joined the Children of God, but not, I'm assured, as a result of finally hearing the Softs perform.)

ONCE ENSCONCED in the capital, the quartet set about hunting out gigs.

Allen, who knew Hoppy and the Indica people, hustled a regular spot opposite the nascent Pink Floyd at Tottenham Court Road's UFO - though the Softs' first gig in London was a disastrous appearance at the Zebra Club where they were booed off (some compensation being admitted in the surprise recruitment of four French au-pairs as groupies-in-residence).

Ayers, meanwhile had conceived a bizarre plan to sell his songs to The Animals (then well in decline) and, through his subsequent investigations, encountered the management partnership of Chas Chandler and Mike Jeffries. Jeffries promised Ayers that he could get "a fantastic deal" from Mickie Most if the group would let him select chart material for them. The offer was cordially declined - but Jeffries somehow became the Softs' manager, and eventually they later came to regret the fact.

At first, however, it all looked reasonable enough. Jeffries encouraged the band to use Ayers' songs - and even Ratledge could appreciate that what Kevin was doing was more likely to pay the bills at this stage.

A three-day session at De Lane Lea was arranged. Giorgio Gomelsky was to record the band rehearsing Ayers' material and to offer his creative suggestions.

At the end of the final day Jeffries smilingly declined to pay the studio costs and Gomelsky, gathering the tapes in his arms, stormed out of the studio. Five years later selections from these tapes - which weren't even demos - appeared on the French BYG label as sides of "Rock Generation" Vols. 7 and 8. Only Softs fanatics were pleased.

Meanwhile, nomadic American nut-case Kim Fowley had picked up on the New Wave of 67: a dual gig by the Softs and the Floyd at The Roundhouse. Trying in vain to secure the latter, he moved in on the former - only to discover Jeffries and Chandler already there.

His comradely offer of production help was, however, accepted by the band (even though all they knew of him was a mention of his name on the sleeve of "Freak Out"), all of which led to his special breed of disassociation gracing the B-side of the Softs' first and only single, "Love Makes Sweet Music".

Again recorded at De Lane Lea, the first mix of the A-side featured rhythm guitar by Jimi Hendrix, another Jeffries-Chandler signing, who happened to be down the corridor in the next studio doing his debut single, "Hey Joe". The two groups dropped in on each other's sessions and became friendly - to the point where Hendrix invited Wyatt, Ayers and Allen to do the back-up vocals on "Stone Free". Finally, however, both swap-over appearances were rejected in favour of alternative takes.

The Fowley-Ayers collaboration "Feelin' Reelin' Squeelin' " went out in midsummer as the most uncommercial A-side in the world - until, one week later, Polydor flipped the side and The Soft Machine soared to the lofty eminence of number

28 on Radio London's Fab Forty. (For connoisseurs: the name "Ellidge" on the credit listing is Robert's real name; Wyatt is a stage-name coined from that of poetic Elizabethan ancestor Sir Thomas Wyatt - and, in any case, Ayers wrote both sides.)

NOTHING MUCH came out of the single and Polydor appeared less than manic over the prospect of an album, so the Softs followed the advice of their cherished eminence grise Henry Henriod and departed upon the hour for France in the company of The Real Mike Chapman, a large stentorian figure prone to the endless declaiming of his "flow-etry" over the P.A. during rock concerts (as per 14-Hour Technicolour Dream chez Alexandra Palace at which the Softs and Floyd performed).

In St. Tropez the band became involved in Alan Zion's production of Picasso's play "Desire Attrape Par La Queue", a "total environment" happening featuring (amongst other attractions) Taylor Meade, Ultra Violet, and the on-stage beheading of live chickens - some years in advance of Alice Cooper, if that's anything to chalk up. It was an incontrovertible success-de-scandale, providing the Softs with the core of their subsequently huge French following, and drawing out the local gendarmerie to break up the event and the home-made geodesic dome housing it.

When, however, they attempted to get back into the U.K., Daevid Allen's visa was allegedly discovered to be expired, his passport out of date, and his hair too long. The other three left him at Dover and headed for Edinburgh to play the festival as accompaniment to Simon Watson-Taylor's production of Jarry's "Ubu Enchainee", a gig secured for them by Mark Boyle whose Sensual Laboratory provided the house-lights at UFO.

Watson-Taylor declared the Softs the most "pataphysical" band he'd ever seen (qv. any translation of Jarry) and, the next time they played Paris, the group were ceremoniously created Official Orchestra Of The College Of Pataphysics and given an award by the Minister of Culture.

AFTER THE much-sung Christmas On Earth concert which polished off the year, Hendrix invited the Softs to go with him on his opening U.S. tour. (At this juncture - the group still regarding themselves as a quartet manque - guitarist Andy Somers, late of the discontinued Dantalion's Chariot, was invited to join in Allen's place; he spent a couple of months rehearsing with them and then disappeared off to the States with Zoot Money in search of Eric Burdon.)

It was the Softs' first taste of the big time and the itinerary was murder: two sets of two-month non-stop gigging, divided by a couple of weeks off to sleep in. Hendrix naturally, occupied 99% of the audiences' attention - but, at the Chicago Opera House at least, the Softs managed to stop the show on their own account.

Between the two halves of the tour, Ratledge went back to London. Ayers and Wyatt remained in their chairs, exhausted. The strain was already pulling the group apart.

For the second lap (the bill beefed-up by the addition of Hendrix proteges Eire Apparent) the pressure was somewhat lowered in terms of set-length - but this time all the gigs were killers. In New York at Madison Square Gardens they lost their nerve at the foot of a bill featuring Hendrix, The Chambers Brothers, Albert King, and Big Brother And The Holding Company. "Nightmarish" is how Wyatt recalls the result.

The final gig was at the Hollywood Bowl. The group merely got through it. The next move they discovered was immediately back to New York to do their debut album under the auspices of famous Black producer Tom Wilson.

Wilson, contrary to popular rumour, was in the studio most of the time, but didn't appear to fully understand the Softs or their music. "We'd do a take," remembers Wyatt, "go back into the control-room - and he'd be on the phone to some girl."

At the beginning of the single week the recording lasted, the group straggled into the studio and loosened up with a "live" take of "Why Am I So Short?" plus an extended blow later entitled (for no apparent reason) "So Boot If At All".

Wilson listened wryly. "I don't know," he informed them when they'd finished, "how I'm going to record this."

In the event, he simply left the band to their own devices. The first take of "Why Am I So Short?" went onto the album, as did the first takes of most of the other numbers. Post-production work mainly consisted of pan-potting everything ceaselessly from channel to channel - an effect that wears thin after approximately one minute.

Nevertheless, it was a great album - a judgement born out by its enormous import sales over the years.

Wyatt arranged most of the material, coming up with a version of an old Brian Hopper song called "Hope For Happiness" which allowed Ratledge ample space to demonstrate his bizarre sound and tremendous flow of ideas - whilst Ratledge and brother Hugh (now roadying for the band) co-wrote "Box 25/4 Lid" in a hotel opposite the Lincoln Memorial for inclusion as the album's closer.

An extensive musical analysis of the Softs has yet to be written - and this isn't the place - but, when it is it'll have to focus heavily on the very surprising improvisatory ability displayed by the band-members so early in their careers. "So Boot If At All" is certainly one of the all-time classic rock ad-libs.

Naturally, the group there upon broke up.

AYERS returned to Majorca to write songs. Ratledge flew to London and began to compose some of the highly complex scores the Softs would perform in a year's time.

Wyatt stayed on in New York at the Chelsea Hotel, writing "Moon In June" and getting to know the city.

As winter advanced, he left for Los Angeles, there staying with first Hendrix and then Eric Burdon, writing all the time and recording two demo albums by himself. The first featured "Moon In June" in an extended form, the second fragments of old material by Hugh re-arranged and provided with lyrics - the pith of which eventually turned up as Side One of "Soft Machine Volume Two".

Finally Probe resolved to release the first album. It sold fast.

They called Wyatt asking him to get the band on the road again. No band.

He phoned Ratledge, who guardedly promised to give the matter his consideration. He tried to contact Ayers - but the only thing anyone knew about him was that he'd flogged his bass to Mitch Mitchell and thereafter disappeared.

Then - Brainwavesville! Hugh Hopper still wandering the States, was contacted a day before he'd promised himself to sell his bass and buy a motorbike.

The new trio congregated in Wyatt's room in his mother's London house in February 1969, and began to rehearse.

Part Two Next Week (We did it again)

|