| |

|

|

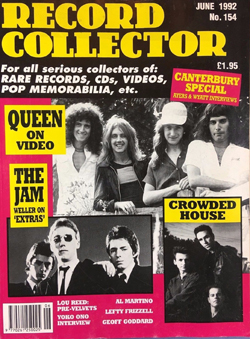

Robert Wyatt - Record Collector N° 154 - June 1992 Robert Wyatt - Record Collector N° 154 - June 1992

ROBERT WYATT

ROBERT WYATT

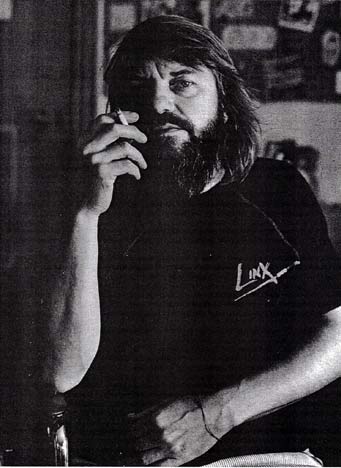

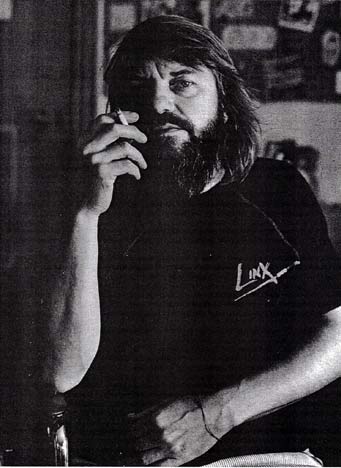

MARK PAYTRESS MEETS THE INSPIRED AND POLITICALLY-COMMITTED SINGER & WRITER

Of all the active Canterbury-based musicians who came to prominence during the Sixties and early Seventies, Robert Wyatt retains the critical and musical edge. Over the years, he's transformed himself from a drummer with a keenness for inventive solos into a songwriter, and interpreter, of the highest calibre. His delicate voice is instantly recognisable, even if it sometimes seems to go unheard outside the close-knit world of musicians and critics. Elvis Costello wrote the classic "Shipbuilding" for him; countless others cite him as one of the finest singers in contemporary British pop music.

Wyatt is a contradiction. A drummer-turned-singer with a capacity to reduce the hardest of souls to tears with a few bars of verse; the avant-garde jazz fan with an uncanny knack of writing memorable ballads; and the self-confessed musical doodler who likes nothing better than to construct soundscapes in his music room, while retaining a vision that extends far beyond national and cultural boundaries in search of meaningful songs to cover.

When he left the Soft Machine, that group was entering its final, least inspired phase. Wyatt released one patchy solo album, "The End Of An Ear", before forming Matching Mole, a criminally overlooked outfit from the early Seventies who, like Henry Cow, reintroduced political polemic into the broad spectrum of popular music.

In 1973, Wyatt's musical career was jeopardised after an accident left him unable to walk. Since being confined to a wheelchair, he's made the somewhat inevitable switch from drum-kit to keyboards and percussion instruments, and his work has taken - on an intensely personal style, sometimes haunting, at other times warm and profoundly moving. His acclaimed series of solo recordings have taken him into the Top 30, seen him forge links with the post-punk independent scene, and work with some of the most accomplished songwriters of recent years.

Back in the Sixties, it was Robert Wyatt's intricate, jazz-inspired drumming which won him most praise. His occasional vocal excur-sions — high-pitched and sung with a lisp — were often regarded as a gimmick, a view enhanced by the nonsense lyrics that were a feature of the early Softs material. Then came "Moon In June", his side-long contribution to the band's "Third" album, a piece brimming with inventive melodies and musical inspira-tion, which revealed Wyatt's true capabilities as a songwriter. This talent was honed down for "0 Caroline" from the first Matching Mole album, a rare piece of originality in the often hackneyed world of the romantic balladeer.

|

|

|

Wyatt re-emerged with the self-explanatory "Rock Bottom" album in 1974, a poignant collection of song-based material infused with the inquisitive passion for musical adventure which always informs his work. Last autumn, he returned with a new album, "Dondestan", which received the usual plaudits from the critics, and this year is likely to see the release of some notable archive recording; on Recommended and/or Rough Trade Records.

When I spoke to him, Wyatt — one of the most thoughtful and entertaining interviewees I've ever encountered — was probably keener to discuss the current state of political opposition in this country (and this was before the election!) than trawl back through the memory banks, past the pre-accident barrier, an era which he now claims an amnesia for. You might not find exactly which Soft Machine track it was that Hendrix played on, but you will discover some acute observations on the development of popular music throughout the course of the interview.

Record Collector: There's a melancholy feel on your latest album, "Dondestan", particularly on the tracks where you set music to your wife Alfie's lyrics, which contain a lot of natural imagery. Is this indicative of a kind of retreat from the outside world on your part?

Robert Wyatt: I can't speak for Alfie. She didn't write them as song lyrics, but as a group of poems called "Out Of Season", which were written while I was working in Spain. It was winter, and we were in a holiday area out of season. Being in such an artificial place built for tourists was particularly strange in winter when no-one was there: it had a very strong atmosphere, very specific. The sole person you'd meet would be a West African trinket seller with only abandoned dogs to sell them to. The songs I chose tended to be just about that atmosphere, being on the beach by the sea, literally at the edge of things.

RC: The political content that many expect to find on a Robert Wyatt record eventually surfaces on the second side. Tieing in with what I may have misread as melancholy is "CP Jeebies", which appears to be a veiled attack on the state of the Communist Party. You've been a well-known member of the CP for many years, but a line like "there will be nothing you can put your finger on" seems to hint at the Party's abandonment of Marxist principles in recent years.

RW: I'm glad that's apparent, yes! But I would say it's more personal. When I joined the Party in the late Seventies, the people I actually liked and got on with were very often the ageing battled-scarred anti-Fascists who'd been in it since the Thirties and had been through a thing or two. There was a plumber who, despite the opportunity to get promoted, chose to stay at the hard end, and really lived the meaning of what he was doing. We used to go to "Morning Star" bazaars and I completely fell in love with the people there.

|

"At Last I Am Free" was coupled with a fine reading

of "Strange Fruit"

on this 1980 single.

|

But then I felt disappointed when a much trendier bunch of post-Beatle people picked up on it, and sat around making sarcastic jokes about these old people because they listened to Paul Robeson and didn't know about what was going on today. I didn't like those people at all! I felt I was being patronised — "Oh, we've got a musician, a real useful badge for our new image." I wasn't interested in helping the right wing do what they do so well anyway, which is laugh at old lefties. Nearly every other Radio 4 play was doing something like that. It's too easy, and it's ageist as well.

RC: Do you see yourself as an artist in opposition?

RW: I don't think the rock idiom itself is inherently revolutionary. I use what comes naturally to me, which is playing music. I can imagine and have seen situations where people who sing songs can be part of a general psyching up for a movement, but I can't see how it could possibly ever be the basis for one. So I see myself as a supporter, a cheer-leader, but rock music is not a substitute for real politics.

The reason I joined the Communist Party during the late Seventies was that I couldn't see rock groups' pose-striking attitudes as changing anything or presenting the slightest challenge to the establishment. There's a lot of that in rock'n'roll, all that "I'm frightening the grown-ups" nonsense. It was conceited.

I left the CP a couple of years ago. It just seemed to be a launching pad for media pundits. I can see no difference between the stance of "Marxism Today" and the David Owen/SDP viewpoint. When I first said that, I was told I was just being provocative, but later on, they took on board a great deal that. I don't need that. I left the Labour Party in the first place because there were too many people like David Owen in it. At least we had a good laugh thinking up some new titles when "Marxism Today" asked readers to send suggestions for its new name!

RC: As part of the Soft Machine in the late Sixties, how much was there a sense that you were chipping away at established styles at the time and forging something new?

RW: I can't really remember what we thought. But if we did think we were changing the world or loosening the bricks of the establishment, I'd have to say that I think we were probably wrong about that. Any thoughts that I may have entertained in that area were crushed by hearing the group being played on Radio Free Europe to prove how wonderful the West and the establishment is. And so, on the contrary, I think pop and rock has helped the establishment to become more adaptable. No real power shifts have happened.

|

"Stalin Wasn't Stalling" was a reminder of the

Soviet

Union's crucial role in the last War.

|

RC: The sleeve-note for the second Soft Machine album spoke of "music for the mind", as if you were actually rejecting dance music.

RW: It wouldn't have been me who put that on there. That's the kind of remark that would have led to me leaving! It could have been somebody at the record company, but as we couldn't play dance music at that time, it's purely academic anyway! When we started, we did play James Brown medleys, and aspired to what Georgie Fame and Jimmy James and the Vagabonds were doing, but in a provincial, clumsy way.

RC: How did Soft Machine end up playing at the Proms?

RW: That actually happened because a composer, Tim Souster, who had written a piece for his spot, still had half the evening to fill, so he thought he'd be naughty and get in a rock band. There was a certain amount of fluidity at that time amongst certain musicians, it was fairly open-ended. I don't think it was a particularly good gig, though: the Albert Hall isn't a very nice place to play.

RC: Can you recall the Soft Machine playing any gigs before the IT benefit in October 1966 as the Soft Machine and not as the Wilde Flowers?

RW: I remember some of us playing in proto form at the Establishment nightclub: me, Hugh Hopper and Daevid Allen. And I remember another event where we played at the Marquee one night when they also had Donovan and a sitar player, and free music by AMM, but I don't recall what we were called. I seem to remember the first gig where we used the name was at the Roundhouse, but I could be wrong.

RC: There's a studio out-take that purports to be Jimi Hendrix and Soft Machine, but the vocalist is certainly neither you, Kevin Ayers nor Hendrix. Do you recall any studio jams, and can you confirm. Hendrix's presence on either side of the first single?

RW: I seem to remember that he came in and put some rhythm guitar on one of Kevin's songs that came out on single. Because we had the same manager, we'd sometimes be in the same studios at the same time, but I can't recall any specific occasion.

RC: Why did you leave the Softs after the release of "Fourth" early in 1971?

RW: I don't know why I was ever in the Softs! I suppose I wanted to work with musicians that I got on with, could talk to and share ideas with. We'd got together because we were the only ones who could play the appropriate instruments, but when we got to London, we started to meet other musicians. It was exciting getting the band well-known enough to headline gigs, but the last vestige of adventure left it at that point.

RC: Wasn't it getting musically sterile?

RW: Yeah. I'm not particularly interested in English jazz-rock. Different musical textures were forming in my head, which were not just related to drumming on endless rehashes of half-remembered Eric Dolphy solos.

RC: Were you pleased with your first solo venture, "The End Of An Ear"?

RW: It was good fun doing it. There was a great feeling of throwing off the corsets. I couldn't believe my nerve, actually — playing piano on a record!

|

"Arauco" / "Caimanera" was probably Wyatt's

most

artistically successful Rough Trade 45.

|

RC: By 1972, you'd formed Matching Mole, who almost uniquely at the time, introduced politics into rock music.

RW: A lot of people haven't noticed that: they assume that really only started to happen in the late Seventies. At that time, the world seemed to become more solid around me, and I felt more assertive and willing to try and not be part of this 'setting' mould, whereas in the previous decade, there was a sort of feeling that — despite what I said earlier — it was all up in the air, that there could never be another Vietnam War, that racism and colonialism could soon be over. But by the early Seventies, you could see a narcissistic Englishness settling in the ground around you.

RC: Since your accident, you've consistently moved closer towards a song-based format. Do you miss collective music making?

RW: I get the sense of working with people in other ways. It's almost impossible to do a solo thing even if you want to. If I'm playing drums or piano, I'm thinking about previous drummers and pianists that I've listened to, so they're part of a gang in my head that I'm having conversations with. And then choosing other people's material, whether it be Latin-American or old gospel songs, to me that's a kind of a communion too. And you're always working with the engineer. It's always like a kind of blind date when you go into the studio — what's he going to be like?! So never felt in danger of being alone. Music making isn't like that. It is a social activity.

RC: Why did you stop making music after "Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard"?

RW: I got overwhelmed by other things that seemed to be more interesting, and embarked upon a process of completing the higher education that I never had, having left school early and gone straight into washing-up and working in a forest. I started to become interested in learning about things that I'd been too busy living before to get round to. Alfie and I used to really enjoy watching the Open University, with these extraordinary professors and their blackboards and charts. I'd watch them all, but particularly those ones that dealt with communication, education and politics, and the relationship between Europe and other countries. That became far more interesting to me than playing musical instruments and being with musicians.

Alongside that, we started going to the London Film Festival, which was akin to a psychedelic experience. We'd see something like 30 films in a fortnight, including many that would probably never get shown again — films from places like Senegal and Java. That was an extraordinary experience, the most exciting barrage of stimuli I'd had since I discovered jazz as a teenager.

RC: Did you see punk rock as a more effective disturbance of the status quo than Rock In Opposition groups like Henry Cow, whom you were loosely affiliated with?

RW: I liked the music of the late Seventies. I thought the Sex Pistols were a wonderful group and I loved Poly Styrene's lyrics for X-Ray Spex. I actually became more interested because it existed side-by-side with reggae. There was a new generation of black youth that seemed to be less English than their bus-driving, nursing parents, who'd been making more of an effort to be more English but who hadn't really been welcomed as much as they might have been. This new generation didn't bother trying and instead began recultivating rural Jamaican patois and all that. It was a grass-roots "fuck-you-too" movement, which actually was a great inspiration for punk alongside it.

It really climaxed in the Two-Tone era when people began digging up the old ska records. I loved Two-Tone. That was really just about the last era of pop/rock music that I felt totally at one with. Jerry Dammers and the Beat and all those people — I thought they were lovely. That whole late Seventies environment really was like a breath of fresh air.

|

Ivor Cutler's "Grass" was one of the later 45s

in the Rough Trade series of cover versions.

|

RC: And provided the inspiration that led you directly to Rough Trade?

RW: Yes. I felt much more at home among that generation of musicians and the people at Rough Trade. It was like the days when I was a teenage jazz fan. All the labels then were indies, and it was very much that kind of atmosphere, disturbing the grand empire of accountants and lawyers of the major companies.

RC: Was it a definite political statement then, signing to an indie?

RW: No, I have to say it was more personal because I liked them. The songs that I sang around that time, some drawn from Chilean and Cuban culture, perhaps made the point that while there's some really tough people on the front line of the fight, they actually sing very gentle ballads. South American revolutionary songs, which are sung by guerillas in the mountains, sound to us like "Come Dancing" music. And I thought that was very interesting and a point worth making. There is never a simple equation between making a racket and being dangerous and political activists. It's much more complicated than that.

RC: Don't you think that the growing sense of internationalism in music has, like the sound of the Sixties underground, now been incorporated into the mainstream?

RW: Yes. People are really getting interested in Cuban music, but it's almost invariably played by Cuban exiles in New York or Puerto Ricans doing salsa-fied version of Cuban music. Nobody's allowed to say Cuba's a hot-bed of wonderful music because it's seen as a non-country. So despite this recent upsurge in interest in Latin-American music, it by-passes the people who are actually living in Cuba and enjoy being there. It might have been an international celebration, but it's just become part of the cycle of appropriation of other people's stuff.

RC: You've rarely appeared in concert over the past 15 years, bar a couple of memorable guest appearances with the Raincoats and with Henry Cow. Is that something you miss?

RW: No I don't. I still have nightmares about twice a week about playing live. I used to drink myself under the table in order to pluck up enough courage to go on stage. I was always more interested in having the musical ideas and working them out than in the presentation.

Even going into the studio is a bit like performing. I get nervous. But that's what I have to do to make records. At home I have a four-track cassette, a couple of mikes and the sort of instruments that you hear on my records, and that's enough for me. I'm more interested in getting the bare bones of the music right — the words, the chords, the tunes, the rhythms. I don't like to dwell on the fancification of it all.

RC: But there are a lot of textures on your records.

RW: Actually I did spend quite a lot of time at home preparing this record, working out the layers, so that I can go into the studio and do it quickly. So perhaps it is fancification after all, getting the right textures and sounds to go with the words.

RC: Can you remain optimistic about the political and social concerns which has inspired your music?

RW: No. I heard the news the other day and the whole thing was basically Pentagon newspeak. The qualification for being a news-reader seems to be, "Can you read White House press releases?" It's never been more pathetic, in my opinion. We're really veering towards an American political system of identikit Republican and Democrat parties. And I think that's sad for the rest of the world because it means that the neo-colonialist practices are more safely established now than they were at the beginning of this century, and that means that a lot of people in the world are going to be in for a hard time for a long time. But I'm prepared to cheer-lead almost anybody who's still willing to have a go.

|