| |

|

|

Tough

Guys Don't Dance - Bill Nelson meets Robert Wyatt - originally

appeared in the August, 1992 edition of Musician magazine

(US) Tough

Guys Don't Dance - Bill Nelson meets Robert Wyatt - originally

appeared in the August, 1992 edition of Musician magazine

(US)

TOUGH GUY'S

DON'T DANCE

BILL NELSON MEETS ROBERT WYATT

| |

An extraordinary dialogue between two kings of

the underground. Nelson and Wyatt have each spent

decades producing music of depth and personal vision

for a small, devoted audience. Each continues to face

enormous hardship in trying to get his music out.

You think you know tough guys? Meet the real thing.

|

|

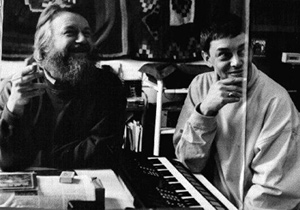

Bill Nelson meets Robert Wyatt. For 20 years they've bucked

the system and have been making music at the edge of rock.

Two vets discuss the never-ending battle.

The first time Bill Nelson met Robert Wyatt, in 1974,

Wyatt asked for his autograph. Nelson, the Yorkshire-born

singer/songwriter/guitarist, was just starting as a professional.

He'd released a limited-edition solo album called Northern

Dream and formed a band, Be-Bop Deluxe. The solo album

caught the ear of legendary BBC DJ John Peel, who played

it on his influential Radio One show. Peel must have been

impressed because he invited Nelson to his wedding. Among

the celebrities in attendance was Wyatt, who'd established

himself as a drummer, vocalist and writer for the Soft

Machine and Matching Mole before falling from a third-story

window and permanently paralyzing his legs. Nelson admired

Wyatt's work, but couldn't get up the nerve to start a

conversation. Wyatt had heard Northern Dream and liked

it. He wheeled his chair over to Nelson and asked, "Could

I have your autograph?" Nelson said, "Only if

I can have yours."

The second time Bill Nelson met Robert Wyatt was for

this interview, nearly 18 years later. "You haven't

changed at all," Wyatt said cheerfully to Nelson.

Maybe he hadn't, but much had happened to both of them.

Be-Bop Deluxe recorded six albums, getting a British Top

5 hit with "Ships in the Night" and achieving

moderate cult status in the U.S. In '78 Nelson formed

Red Noise, which made one brilliant album that went nowhere.

After that, he began a solo career (literally solo - most

of his post '79 music has been recorded at home without

collaborators). On the one hand, he produced a series

of instrumental records on his own Cocteau label that

could almost be called "ambient music" if they

weren't so sophisticated. On the other, he made left-of-center

pop gems like The Love That Whirls (1982), Vistamix ('84),

Getting the Holy Ghost Across ('86) and last year's Luminous,

filled with great radio songs that somehow never made

it to the airwaves.

Meanwhile, Wyatt recorded two discs for Virgin in the

mid-'70s and then dropped out of music for several years.

He resurfaced in 1981 with a stunning series of singles

that were later compiled on Nothing Can Stop Us. His music,

like Nelson's mostly recorded solo, was more stark and

somber than before, his lyrics more political. One thing

hadn't changed, though: his heartbreakingly tender singing.

For the first half of the '80s Wyatt was relatively prolific;

then, after '85s Old Rottenhat, he vanished again, emerging

after six years with Dondestan, perhaps his best album.

This interview took place over two days in March at Wyatt's

cozy 19th-century house in the Lincolnshire town of Louth,

a charming village of narrow, winding streets, antique

buildings and crooked alleyways isolated by miles of flat

green fields and marshland. There's no railway station,

and the nearest noteworthy town's about 30 miles away.

To most of Louth's inhabitants, Robert Wyatt is simply

the guy in the wheelchair, who moves around faster than

some cars. Almost nobody here knows about the 30 years

he's put into music, and he likes it that way.

At the time of the interview, neither Nelson nor Wyatt

had much reason to be cheerful. Nelson was in the middle

of a lawsuit with his former business manager who, Nelson

says, is illegally claiming full rights to the Cocteau

catalog. He says Virgin has agreed to release three new

Nelson albums provided they get the back catalog too.

So until the ex-manager lets go of it, Nelson says, there's

no deal. What with mounting costs and the lack of cash

coming in, he may lose his house, his car, his studio

- in short, everything he owns.

Although Wyatt's living in comfort for the first time

in years (thanks to friends of his wife Alfie, who gave

them the money to buy the house in Louth), his future

is also uncertain. Rough Trade, the label he's been signed

to since 1981, has gone bankrupt. Though Gramavision is

licensed to distribute his records in the U.S., he is

essentially, like Nelson, a man without a contract. And

like Nelson, he's seen no money for some time.

For decades Wyatt and Nelson have struggled on the perimeter

of pop, often with little reward save the devotion of

a select group of listeners. They simply love what they

do. They are, as Nelson put it, representatives of "two

complementary aspects of the human condition - the inward-looking,

spiritual side (Nelson) and the outward-looking, political

side (Wyatt) that's concerned with how that spirit deals

with the rest of the world." And, as Musician quickly

learned, they are talkers of a very high order. When the

articulate, soft-spoken Nelson and the earthy, wisecracking

Wyatt sit across the table from each other drinking wine,

laughing, and talking about music in the company of Wyatt's

comfortable old mongrel, Flossie - you can't help wishing

the conversation won't stop.

MUSICIAN: It seems there's a small group of English

musicians who spend most of their time staying home and

making records, including both relatively famous people-Peter

Gabriella, XTC-and some lesser-known ones-The Bevis Frond,

Peter Hammill And then there's you two. Do you see yourselves

as part of this - if you can stomach the apparent contradiction-group

of

individualists?

NELSON: Sometimes I wonder whether all these people

had train sets when they were kids. I know Andy [Partridge,

of XTC] and I know Peter, and there's something of that

in me as well. It's the boy in his loft with his gear.

Life passes him by. He's living inside his head all the

time. It's an obsessive thing, and you tend not to have

time for other people. It's a sad, sick reflection on

what we've become. [laughter] I'm terrible sometimes,

I don't want to know that there's a world outside that

door.

WYATT: Not all of the arts are intrinsically performing

arts. Composers, painters, novelists, poets are solitary

workers. That's what the job requires. You have to get

into a state of mind which too much human traffic can

destroy. To use a crummy metaphor, you're working in a

pond and it has to be still; otherwise you'll never see

to the bottom. In music this may seem odd, because people

think of music as something that's performed. But compare

it with painting, and you see an analogy that's very obvious.

A lot of English pop music of the '60s came more out

of the art college tradition than the conservatory tradition.

John Lennon, Pete Townshend, Brian Eno, Ian Dury, were

all art students. In the '50s, it was one of the only

places where kids could go who didn't have qualifications,

who weren't articulate or impressive in academic fields.

They could suddenly feel welcome, allowed to do their

own thing. They could become kings of their imagination,

instead of failures in some system they couldn't understand.

I was only in one for three months, but it has to be acknowledged

as an English thing.

NELSON: I'm from a working-class family, and I

wasn't happy at school but I always liked painting. When

I got to art college, it was like going to heaven; everything

that made me an outcast before made me acceptable there.

WYATT: I don't think this maverick thing you're

talking about comes out of the music colleges. These mad

breakthroughs that have taken place from John Lennon onwards,

totally unpredictable things that set off a chain reaction,

that has to be attributed to the anarchism of art colleges.

By that I mean the lack of hierarchy, the governmentlessness,

the feeling that you could be anything you wanted to be.

NELSON: When I was at art college, I used to pick

up the International Times to find out what was happening

in London. I read about Robert's band, and I'd think,

"This sounds wild!' And without being able to go

down there and see for ourselves, we made up our own version

of what we thought was happening. We did concerts with

light shows and the whole thing. Nobody knew what was

going on-'Where the hell's this coming from?"-because

it was only three of us reading the International Times

who knew what was happening anywhere south of Barnsley.

WYATT: That's fantastic.

MUSICIAN: Robert, how did you become apart of that

underground London scene in the mid-60s that Bill thought

was so wild?

WYATT: I'm afraid I may have to dodge that question,

because ... well, people think I must have problems talking

about my accident. But I don't; what I have problems talking

about is what happened before the accident. Rock Bottom

[1974] and beyond, that I see as me. But my adolescent

self, the drummer biped, I don't remember him and I don't

understand him. I have a hard time dealing with the way

I was before; it's almost as if the fall affected my mind.

I see the accident now as being a sort of neat division

line between my adolescence and the rest of my life.

This was how the accident went: in order, wine, whisky,

Southern Comfort, then the window. The doctor was amazed.

He said, "You had to have been really drunk to fall

in such a relaxed way.' If I'd been any more sober, I

probably wouldn't be here today; Id have tightened up

with fear shattered. It's been a long time now and it's

been hard, but at least the top part of me works, though

I'm never quite sure about what's going on in here[points to his

head]. I do know exactly what I can and can't do, and

that makes it easier.

MUSICIAN: Which players inspired both of you?

NELSON: When I first started out, I played in groups

that did everything- country & western, jazz, blues,

rock'n'roll, psychedelic. At one time I just wanted to

get all the technique together. I had a turntable that

went down to 16 so I could slow it down: "Ah, that's

how it's done." First it was Duane Eddy, Hank Marvin

and the Ventures, the twang. Then Beck and Clapton, and

Townshend, more for his attitude than anything else. That

little flourish in his chord playing, which is a sort

of Wagnerian thing - every guitar player's got that in

his book of tricks now, but Townshend was the guy who

did it. And if you want to hear the entire catalog of

what a guitar can sound like, you have to listen to Electric

Ladyland. Nobody yet has gone much further than Hendrix.

WYATT: Music was my way of escaping from school.

Mostly jazz; old as I am, I'm more old-fashioned than

I need have been. I did have a romantic association with

pop records of the time-Roy Orbison, Buddy Holly, Eddie

Cochran-but that had to do with where the girls were.

Whereas Jazz was my comfort when I was struggling with

homework that I couldn't make head or tail of. Miles Davis'

voice, getting lost inside a Mingus arrangement, being

carried along by the band, chucked from one soloist to

another - that saved my soul as a schoolboy.

Then Coltrane and Miles Davis encouraged me to listen

to Indian music. At that time more musicians were coming

from the Indian subcontinent to England, so Indian music

was around. And the fringes of Europe generally, where

European harmonies meet something else, that's interesting

to me. Not for some ulterior motive, I'm just an aural

tourist.

MUSICIAN: Both of you have definite Eastern influences

in your music.

NELSON: It's weird. The first time I worked with

Yukihiro Takahashi it was for an instrumental piece. He

had a half-completed track and no ideas for melody lines.

So I put some things down using the E-Bow. And he said,

"God, you sound more Japanese than I do.' [laughter]

WYATT: It's just a question of using scales which

tend to be identified as Oriental or non-European. But

often you'll find they're discarded versions of Greek

modes, perhaps from someplace like Macedonia. You hear

it in Bulgarian folk music to this day, which is probably

closer to ancient Greek music than we realize. I've always

liked scales that had an ambiguity about whether they

were major or minor. What I like about flamenco is they

use gypsy scales, where the second note is only a half-step

up; both our major and minor scales go up a whole tone

on the second note. That half-step's a North African thing,

because a lot of Egyptian scales are like that.

MUSICIAN: How important was John Peel for your

musical generation?

WYATT: I think you'd hardly recognize English rock

without him.

NELSON: After I first heard Peel, I started buying

American imports, because you could only hear them on

his show. And that influenced the way I played. Then he

picked up on my things and played them, so it's almost

like showing me what was possible and then giving me space

to do it myself.

WYATT: By the way, the bloke who put out The Peel

Sessions in the States made a fortune. None of us got

much of a look-in on that. It's depressing that the memory

of the Peel days is spoiled by people who think, 'Oh,

these lot are a bit innocent, they're looking the other

way, we can clean up."

NELSON: You know Imaginary Records, that put out

Luminous? They asked, "Why don't we get the Peel

sessions that you did with Be-Bop Deluxe? Would you mind?"

I said no, there's some good stuff there; in fact, some

songs we did for those sessions never got recorded. There'd

been no plan to release the Be-Bop Deluxe Peel sessions.

But as soon as these people found out that Imaginary were

thinking of doing it, "Ah well, we might wind up

putting them out." It's still not resolved.

WYATT: Columbia has a load of stuff I was involved

in, both in Soft Machine and Matching Mole. It comes out

here and there, on Japanese imports or whatever. But if

any of the musicians phone them up to get a handle on

anything, they say, 'Sorry, he's out of the office,' 'Oh,

you want the legal department," 'He's not here....'

They treat musicians like crap, unless, I suppose, you're

Wynton Marsalis. And it's a shame, because I know people

who want to put that stuff out but CBS won't put it out.

So I'm getting publicity for stuff that nobody can buy.

NELSON: All you need is one Top Ten mainstream-play

record and that stuff would just roll out. It's waiting

for that moment.

WYATT: That's right, and whether you earn a living

in the meantime is not a major concern.

NELSON: I've had a lot of pressure from people

on the business side. Normally I'd ignore that, but sometimes

it looked like by the end of the week we wouldn't have

a roof over our head. Then you start thinking, 'Maybe

I could compromise...." You always regret it. A few

people make a career from music and are utterly uncompromising.

They don't give a shit what anybody thinks, they just

do what they do. I admire that. It's the only way.

WYATT: Some people can't do that. For kids from

tough backgrounds, the only way out is to "make it."

The only other choice is the dole or a boring job in the

local factory, and they want to make something more of

things. So they go for success. The people at Motown said,

"We want a classy black record label," and they

groomed it to be an imaginary mainstream America. It was

a bit utopia but I find no fault with that, because what

were the alternatives?

NELSON: And they actually produced decent music.

WYATT: Wonderful stuff. Marvin Gaye knocks me out

to this day. You know, politically speaking, black America

has been a failure - but often to what's come out of it!

All this music that's been my sustenance and made life

worth living. Never underestimate the power of failure.

NELSON: I played a long time before I ever thought

of making a career from it. One of the spurs in the early

days to practice a bit harder was what happened the first

time I gave a public concert at school: Suddenly girls

would talk to me. I mean, sex had a lot to do with it.

WYATT: Oh yes! He's got a point there...'Sex had

a lot to do with it.' That's gotta be my epitaph. [laughter]

Especially since I couldn't dance... I mean, how do you

meet them? Let's see, a drummer gets to meet them... right.

Lester Young started out as a drummer, and he figured

that the saxophonists got the nicest girls because they

wouldn't wait for the drummer to dismantle his kit. [laughter]

So he changed to saxophone, and became one of the most

important players in the history of the instrument.

NELSON: I've worked with young bands in the studio,

and you discover people's motives quickly. For a while

now there's been a push for music to be a career move,

which I think is dangerous. That's forced upon us by the

economic climate we live in; there's desperation in this

country. Not only do people not have money, but they lose

self-esteem. And the myth that pop music creates is so

glamorous to younger people. This can show they've achieved.

But when they've got into it, they find out it's all a

front and they're still stuck with nothing at the end

of the day. WYATT: They're calculating career moves, and

that's okay, but it can be the wrong place to take your

talent ... that week. Talent is a tough taskmaster, first

of all, you never know whether you've really got any.

But you have to follow it, you can't afford not to. It

tells you what it needs. And if you have another master,

you're just thinning it out.

MUSICIAN: You would say that the audience is second,

and when you're working, you do it primarily for yourself

NELSON: It's a totally selfish experience, creating

- it has to be. It's one of the few things where you have

to deal entirely with yourself, with your own experience

and limitations. But despite that, it still will connect.

I think the more true you are to yourself, the more chance

it has of connecting with other people, because there

are common threads under the surface.

MUSICIAN: What are your views now on the progressive

scene of the '70s that you were both, to some extent,

apart of?

NELSON: The '70s I spent mostly on tour. I was

so wrapped up in what the band was doing that I didn't

notice anybody else; I was dismissive of other people.

I don't see anything important about what I did then-still

[laughs] although EMI re-released the records and people

still liked them. But I can only listen to them and hear

a young guy struggling with ideas.

I went through a period of buying music that was difficult

to play and difficult to listen to. The idea was, if you

even pretend you can listen to this, you must be pretty

bright. It's like watching people with muscles flex them.

They're all oiled up and you can see there's years of

work gone into this. But a lot of those people who had

all those muscles never actually went out and hit anybody.

They didn't do anything except pose around. And the older

you get, you see that truth doesn't reside in incredible

shows of technique. I used to do 20-minute guitar solos,

but I don't anymore; some might call that a retrogression.

But I think, why waste your energy?

WYATT: As a drummer, I tried to play things people

needed, but at the same time I had my own ideas, and I

didn't know anybody except me who was interested in them.

[In Soft Machine] they wanted a drummer who could play

in any time signature for very long solos. They didn't

want a drummer who kept showing alarming tendencies toward

turning into something else.

I'd already done what amounted to a solo record, which

was 'Moon in June' [on the Soft Machine's Third album].

I'm not credited with it, but I played it nearly all myself;

I got the others in just to do a sequence towards the

end. They didn't want to play it and I was embarrassed

to ask them. I don't think they liked me having ideas,

but I don't know-, we didn't talk to each other much.

I thought, "If I weren't in a band, I could do more."

But obviously, if I wanted to work as a live musician,

I had to be in a group. So I wasn't released to concentrate

on what was growing in my head, funnily enough, until

I found myself in the wheelchair. Then I couldn't live

a group life anymore, so I had to take control. And everything

got simpler.

MUSICIAN: Didn't you do some live performing after

the accident?

WYATT: I did two or three gigs, and the practical

side was very difficult; I was nearly fainting with exhaustion

onstage. I suppose vanity prevents me from wanting everybody

to know that I'm incontinent, but I am, and that's a big

problem when you're on a stage somewhere. It's too embarrassing.

If I go anywhere or do anything, it has to be carefully

worked out.

MUSICIAN: What are your feelings now on the punk

revolution of 76-77? It really seemed to change your music,

Bill - Red Noise sounded so different from Be-Bop Deluxe.

NELSON: I was listening more to electronic music,

and people like the Residents; I'd always liked Terry

Riley, Karlheinz Stockhausen. I was using a synthesizer

guitar instead of an ordinary guitar, and putting the

snare drum through fuzz boxes, making drum loops, manipulating

tape. Those were the concerns and not so much the punk

thing. The good thing about what happened then-briefly,

before the industry grabbed hold of it and strangled it

to death-was that it opened up possibilities for people

to have a platform to say something. I didn't think the

music was all that wonderful, because it sounded incredibly

old-fashioned. Apart from John Lydon's voice, I thought

the Sex Pistols sounded so dated. Amateur Chuck Berry,

full-stop. But John Lydon's voice was very interesting.

And I still like Public Image, I'm a big fan. I was listening

to a lot of American bands of that period, more than English

ones. I liked Television and Talking Heads.

WYATT: What was I listening to then? Calypso and

Nat King Cole. [laughter] And shortwave, getting the Latvian

version of events. If I heard music that I liked, it was

usually Radio Sofia, Bulgaria. But it's the age-old thing,

the young bullets coming up. I thought they were sweet

little things; Johnny Rotten makes me laugh every time

I hear him. And I tend to like things when they're in

a state of terminal collapse.

I was taken by [Rough Trade's] Geoff Travis to meet some

people, and I thought, 'Do they allow people over 21 in

here?" 'Cause I always think of rock 'n' roll as

being the land of age apartheid. But people were friendly,

they came up and said hello. And I felt at home with them,

except I suddenly realized that they were saying hello

like I used to say hello to an uncle. They weren't saying

hello to a contemporary, and that's a very funny feeling,

because I'd never grown up inside.

NELSON: The industry is so youth-oriented. That

ageist thing is as bad as any divide between the sexes.

WYATT: And you really feel you're just getting

there now. That's accepted in painting, in classical composing.

If we were politicians, we'd be considered still in nappies.

It's a cruel irony, in a way, that just as we reach adulthood,

we no longer belong to anything we can participate in.

MUSICIAN: What prompted you to get back into music,

Robert?

WYATT: Alfie saying, 'We're running out of money

and you can earn it quicker than I can." And Geoff

Travis saying, "If you want to record for us, you

can." I fell into it. I might have drifted away altogether,

except that I think Alfie worried that whatever I was

drifting into didn't constitute earning a living. She

also felt I was fraudulent, because on the marriage contract

she married a musician. You can't marry someone and then

they turn into something else, that's cheating. [laughter]

So she and Geoff got me out of it. But if I didn't have

to earn a living, I'd be quite happy to disappear completely.

I'm not in the music world half the time anyway, I'm somewhere

else. There's a dog to be fed - this is serious stuff,

you know [laughter]. And when I listen for stimulus, it

tends to be music which I have no part in. I'll recreate

Harlem 1940 in my front room, because it's untouchable

and I can build up a fantasy about that that isn't brought

down to earth by any real experience. I tend not to hear

what my contemporaries are doing, especially other songwriters.

I'm almost nervous of it in a way. Since I stay home a

lot, I like music that's comfortable. If you're in the

city rushing about, you might very well want to hear music

that's like a train driving through your skull. But I

don't listen to stuff like that so much. Also, since I

haven't been able to see the world, particular emphasis

has been on vicarious travel.

I've worked with musicians who are really prolific; I

wish I was like that. [Elvis] Costello writes a lot of

songs, they pour out all the time, and I was impressed

that he was so certain. I think Bill's more like that.

I get disheartened, and I spend a lot of time thinking

I just can't do it. Nobody's that noble-if you're trying

to do something and can't get it how you want it, you

go fry an egg. 'Cause I can do that, I know it's going

to work. [laughter] Even out of the amount I do, not a

lot gets out.

MUSICIAN: That's very different from Bill.

NELSON: But don't forget, I've had the luxury of

having my own studio and label. It's like self-publishing;

you can foist it on people and they've got no say in it

whatsoever: "You will see this exists." If I

hadn't had that outlet, it would have been different.

WYATT: Peter Cook, the English comedian, once said

his motto was "If at first you don't succeed, give

up." Unfortunately, he's had an enormous influence

on me. [laughs]

MUSICIAN: Do you miss working with others?

NELSON: There was a time when I struck out just

to see what happens when you play everything rather badly

and only one thing slightly well. [chuckles] At the moment,

I'd crave to have musicians around me to take a skeleton

of a song and say, "Okay, you can go down the pub

for half an hour, we'll make it sound good." But

that's an impossibility at the moment.

WYATT: I don't understand machinery well enough

to do the finished object myself, only enough to get the

ideas down. My room's just a sketchbook, not a painting;

I need people with know-how. The real problem is there

just isn't the money. Usually when you're making a record,

a record company puts up money upfront. Well, our record

company has no money. They can't pay me, how can they

pay someone else? That's the inhibiting thing at the moment.

It's not an abstract thing of 'what would you like to

do,' it's 'what can you do.' And I've ended up just doing

what I can. But there's a kind of pride in that. I made

the great discovery, influenced by Stevie Wonder, that

you can play your own basslines. I thought it wouldn't

sound right, but his are so organic. And by covering everything

himself, he was compensating for disabilities in real

life. There may be an element of that in me as well. I

like to hear that rhythm section, that bass player, that

drummer.....that's me. Even if somebody else could do

it better, it's still a nice feeling. And at least they're

playing within your range of technique. They know the

tune. [laughter]

NELSON: For me, it's also a way of seeing yourself

in a clearer light, because you see everything undiluted.

WYATT: That's very true. Undiluted is a good word.

NELSON: And it might not be brilliant, and it might

not be what you'd like to achieve, but it's honest and

it's a real mirror. Which is why sometimes it's uncomfortable

to listen. I hear everything that's wrong with it and

nothing that's right. Then you get on with the next one

and say, 'This one'll be okay." But it isn't. [laughs]

MUSICIAN: Yet you make such a point of declaring

the imperfections in your work - the broken tape machines

and so forth - that you seem to have a certain pride about

them too.

NELSON: It's a romantic thing. I've put on the

back of my record sleeves that only 14 of the 16 tracks

work and the speaker distorts. It's a charming thing to

write about, but sometimes it's a bitch to deal with.

MUSICIAN: Robert, have you ever put out anything

recorded completely at home, as Bill does?

WYATT: A couple of things. In the early '80s Dave

Macrae, who was the keyboardist in Matching Mole, helped

me out on a couple of old jazz standards, "Round

Midnight" and "Memories of You." I wanted

somebody who had enough of a jazz education to play the

chords right, but at the same time could drain out everything.

I just wanted the skeleton of the tune, but having revealed

it, I wanted the bones in the right place.

MUSICIAN: Trying to get to the skeleton of the

tune seems to sum up your general approach to music.

WYATT: I've been looking for the essence of what

it is I like about a piece. Is it just that one bit where

the harmony changes or that one note or the way that beat

falls ... it's a process of tracing it and thinking, 'Well,

if I'm right, it should stand without any covering."

if it collapses under exposure, then it isn't right and

I've exposed a fault.

I'm scared of doing what happens a lot in music, which

is getting too intoxicated by the beauty of the sound

you're creating or the energy you're putting out to actually

hear inside it. The skeleton of the music can be a very

rickety and inadequate thing that pulls apart once the

excitement's over. That's one of the reasons I'm scared

of expensive synthesizers, because you can just sit on

'em and sound great. I've got a feeling that's more or

less how some records are made. [laughter]

NELSON: I wouldn't in real company admit to actually

being a musician. I'm more of a person who tries, using

music as much as I can get my hands on-which often is

not very much [laughter]-to express something for myself,

about myself, my relationships, whatever. So often my

preoccupations when I'm writing aren't musical ones at

all.

I'm not a great technician. I've had a reputation in

some quarters for being a perfectionist, and I'm not.

I'm a lazy sod when it comes to it; I want to get there

the quickest route possible. If I had more confidence

in myself as a musician, I'd be more thorough, and a lot

of what I do isn't. It's not so much that it's slipshod,

but I have to let things stand because they came out spontaneously

and they're an honest reflection of what I was doing at

that moment. Since I often don't know whether it's going

to be heard by anybody else, it doesn't matter whether

it's perfect or flawed, as long as it's true. So I'm not

always pursuing music, it's something else, but I'm not

sure how to explain what that something else is.

WYATT: We have a lot of difficulty in this context

talking about what we do. When you read about what musicians

or artists do, you're not reading about what I sit down

and think about when I go to work. If I'm full of too

many ideas and theories, it just blocks every route to

getting there. It has to be a physical, instinctive thing,

just you and the instrument and the sound you're making.

All this analysis is retrospective.

Say you sat down and talked with your girlfriend about

exactly why you were about to go to bed, it could kind

of. - -spoil it. And I think a lot of important activity

can be talked out. It's pretentious to use words like

'sacred'; all I mean is that the whole point about music

is it isn't accessible to logical analysis. And I don't

think those of us who make it know quite what we're doing.

Professionalism just consists of knowing which trigger

mechanisms are most likely to work. We turn on the tap,

and what comes out, that comes from somewhere else. Art

Blakey said that music comes from the Creator through

the musician to the audience in one split-second. I understand

what he meant, though he used the word 'Creator.' But

I know Americans are very religious people, I've read

about it in the papers. [laughter]

NELSON: I think you'll find that people who are

committed to music-and, despite Robert saying he doesn't

do it all the time, there's obviously a life commitment

there - everyone I've met with that commitment is very

cagey about going into too much detail about what the

actual creative process is. But if they've had a drink

or two, or they know somebody well, you'll always get

this reference to it coming through from somewhere else.

There's a kind of religious feeling, an awe about it.

You know that it's something you can't trivialize or muck

about with because it's so fragile. There are so many

explanations for where it's coming from, the unconscious

or wherever, but whatever it is, it's intangible. So you

don't feel comfortable talking about it in front of just

anybody.

WYATT: There's actually a hint of apology. We're

saying not that we're at the source of creative power,

but precisely the opposite, that we're simply tools in

the hand of forces that we cannot presume to understand.

Even the best gardener couldn't make a single flower.

He can only understand how to nurture the process.

MUSICIAN: Do you believe there is a musical mainstream

and consciously see yourself as outside it?

WYATT: Stan Kenton was once asked, 'Where is jazz

going?" and he said, 'Well, we're going to Cleveland

on Tuesday.' [laughter] I've always considered myself

absolutely normal. Not only am I in the mainstream, I'm

possibly the only mainstream there is. I write absolutely

normal tunes, I make absolutely normal records, and it

sounds totally sensible to me. People who are deliberately

eccentric must be insane; I have enough trouble just trying

to be normal. [laughs]

NELSON: It's always a shock when you offer something

you've done to someone to listen to and say, 'This is

really commercial," and they go, 'This is weird.

Where's your head?" And you say, 'No, honestly...'

WYATT: That happened to me when Virgin wanted me

to make singles. I'm a girl who likes to say yes, so I

did one [a cover of 'I'm a Believer'] and then another,

and I really enjoyed it. I did 'Yesterday Man,' a major-key,

upbeat, jolly pseudo-reggae thing. I bent all the chords

out of shape and did the whole thing kind of sideways.

And I was so happy with that. They said, 'We're not putting

this out. It's too lugubrious." I thought, "that

must be good," but I got a dictionary, and it's not.

[laughter]

MUSICIAN: Robert, how did you go about setting

your wife Alfte's lyrics to music for the first five songs

on Dondestan?

WYATT: I work from sound, from atmosphere, and

the words have to appear out of that, like out of the

fog. I had some unpopulated landscapes, and what was surprising

was, the words that came were Alfie's and not my own.

She wrote those poems in the mid-'80s when we were in

Spain. I happen to know that everything she describes

is true, like when she describes the wind on the beach

sweeping everything away ['The Sight of the Wind']. Everything

she describes-"a plastic bag caught by a rail"

- that's what we saw. So I wanted the music to give a

sense of the event, the time and the location. I worked

on it a lot, because I wanted the end result to sound

fairly spontaneous. I have to do a lot of work on words

to make them sound like there hasn't been a lot of work.

I recorded the whole LP 10 times at home, a kind of dry

run before going into the studio. What's in this room

is what's on the record. I work at home on the four-track

and get it as near completion as I can, and then I beg

the studio for a bit of cheap time. And I get in there

and work as fast as possible. I have to work cheap because

my records don't sell enough for me to work any other

way. The last expensive record I made was Ruth Is Stranger

Than Richard in 1975. That was with the Virgin lot.

NELSON: That's still selling, isn't it?

WYATT: Yeah, and thank goodness it is, because

I only finished paying for it about two years ago. Virgin

charged me for making the record. They're a clever lot,

you can see how Branson got rich. Everything's collateralized.

Any money that came in from a record, instead of you getting

it, they'd say, 'Well, you're recording again now, so

we'll put it straight back into your next one." You're

always behind, and someone's getting your money. I was

in debt for years on that one, and I thought, "I

can't live like this." So I had to start working

dead cheap. But it doesn't make much difference, because

Rough Trade's going bust. We're all going bust in England,

you've landed on a sinking ship. [chuckles]

MUSICIAN: I guess so. Bill's been telling me all

his horror stories.

WYATT: Well, tell me then.

NELSON: Oh, I'm trying to take some people to court

at the moment, and they're blocking everything. I set

up a label 10 years ago which I funded out of my own income.

The guy I'm suing was my business manager, I hired him

after the label had been set up, to do the administration,

because I didn't have time for that and music. It turns

out he's put things through different companies and various

manipulations until it's ended up all in his name. He

claims that all my work of the last 10 years is his and

not mine. And I've just had a deal ... from Virgin, ironically.

They want to buy the back catalog, which would bail me

out of a lot of problems, because besides appropriating

the label my ex-manager didn't deal with taxes, and I

ended up getting stuck with them. Virgin wants my catalog,

but my ex-manager's claiming that the stuff's his. And

I'm saying he has no right to it. It was my label in the

first place. I set it up and ran it, and I was virtually

the only artist on it! We've got to resolve this, and

all he did was apply for extension after extension for

time to put his defense together. And when his defense

came through, it was a tissue of lies, so that's got to

be taken apart. I could go on for months and months.*

*Nelson's ex-manager, Mark Rye, denies ever claiming

that Nelson's work belongs to him: "I'm simply trying

to get my bill paid. I haven't been paid for the last

five years, and until the debts - paid off I'm not prepared

to let anything go. He had a debt when I took him on,

and he still has one because he spends more DM he earns.

The trouble with Bill is he doesn't understand business.

He's very talented, but when things go wrong, it's always

somebody else's fault."

WYATT: And it costs, doesn't it? Apart from burning

up valuable brain cells?

NELSON: Yeah, the Inland Revenue Bankruptcy Department's

on my back, and I stand to be homeless within a few weeks,

unless a miracle comes out of the sky. Selling the house

would clear up a lot of problems, but I don't know what

to do after that. It's more of a worry because I have

a family; I worry about them being warm and fed more than

myself.

WYATT: Oh, it's a bastard. It's such a cesspit,

this industry. People think we live on a higher plane,

we're artists. But we're talking about the mechanisms

whereby we live. It would be so easy to do a straight

deal: 'You make the records, I'll sell them. Percentage

so-and-so of retail well crosscheck accounts regularly.

You get this amount, I get that amount. Deal? Deal. Right,

sign here.' Why work out all these fucking scams?

NELSON: It's not like we're talking about huge

amounts of money, especially with people like me. My ex-manager

knew how much music I put together on a daily basis. It's

been 20 years since my first record, and I've done over

40 albums. The majority of that has been on the Cocteau

label which he's got his hands on. And I've no particular

faith in the system, or that I'll come out with a fair

settlement. I hope so, and the lawyers say so, but they're

bound to say that, and there've been so many miscarriages

of justice in the past, I don't know.

WYATT: Well, at least you've got a solid body of

work, and you know it's yours. There are laws coming to

our rescue. I'm thinking of the European stuff about intellectual

property and moral rights. There are new laws on the horizon.

The last check I got was for what Gramavision picked up

in America on my last LP, and that completely disappeared

into the Rough Trade debt. So I haven't actually yet made

a penny from Gramavision. It discourages you; you think,

'How can I afford to make any more records?' But I must

say I like Gramavision's catalog, they've got a great

bunch of music.

MUSICIAN: If an artist becomes involved with business,

particularly the huge bureaucracy of a major record conglomerate,

doesn't that immediately compromise the art?

NELSON: There has to be some kind of compromise,

because of the nature of the beast. I always had this

dream that you could change things from the inside, and

I don't know if I've completely shaken it off yet.

WYATT: I remember when they said the Clash sold

out. Well, the lads are only trying to earn a living,

you know! Give me a break. [laughter]

NELSON: That's an important point. If you've put

your life on the line for music as a career, then you

have to survive. A big record company can help make things

more successful for you than an independent label. It's

not so easy to say, 'All major companies are automatically

terrible and corrupt.' I've met some people in majors

who don't give a shit about music and all they want is

whatever freebies come with the job and as much cocaine

as they can get through. But there are some genuine music

lovers as well who've got good taste, who really give

a lot of their time for what for you're trying to achieve.

And I've seen ripoffs in the indie scene just the same

as in the majors.

WYATT: It's a romantic illusion that you can extricate

yourself from the system. Systems are a bit tougher than

that, systems are the way are organized. And you can turn

your nose away so the smell doesn't kill you, but really

you're in the shit with everybody else. I don't think

there's any such thing as an independent record label;

there's no such thing as an independent person. Put a

self-sufficient individualist in a desert without water

and he's dead in a day. A thing that worries me is that,

even in the indies, there's tendency for the music to

be a hastily cobbled-together afterthought, once the serious

business of getting the haircut has been sorted out. [laughter]

Obviously, I have personal reasons for feeling threatened

by that. At the moment I've nervous about how to function

in the future. Because apart from these high aspirations

we've been talking about, we are talking about a job and

trying to earn a living. I'm not getting any younger,

and it's not getting any easier. There are some tough

times ahead. And there's nothing I can see on the horizon

that'll help much, we're on our own.

NELSON: Everybody could make their own records.

It doesn't cost an awful lot to print up a few. I had

this dream once that you could release them like you would

a newspaper, on a regular basis and quite cheaply. People

could try them out and throw them away; they weren't precious

so it didn't matter. But the industry has made people

expect to pay money. If you start offering people cheap

records, they'll think that the music on them is cheap;

there's a psychology that goes with it.

WYATT: In my case, I don't think people are saying,

"Well, we've got Diana Ross, I know what we need

now ... Robert Wyatt!' [laughter] But I don't want to

say anything about my decisions which might cast aspersions

on somebody else's. For example, I personally have had

a very hard time with Columbia, but I also know they've

looked after some musicians I admire very much. Maybe

there's an inadequacy in me that I'm dumping on the record

company. Look at the art industry, the film industry,

the way people run supermarkets. There aren't a lot of

virtuous organizations out there, really. Just the way

things are done is pretty hair-raising.

You may have thought, 'If he's struggling, how come he's

got this nice house?' And I'll tell you. My wife knows

a film actress, and after I had the accident, this film

actress, in an amazing act of generosity, gave Alfie the

money that she'd earned off a film so we could buy a flat.

And it was with the money from that that we got this house.

This isn't music money. Ronnie Scott and Pink Floyd and

a few others also helped set us up. So a lot of what I've

got is due to the generosity of particular people, and

I'm just glad to have the opportunity to say thanks again.

This is indulgent of me, but one man was very nice. I'd

only met him once, and at that time I'd had a blazing

alcoholic row with him - I can't remember what side either

of us was on or what the details were, but there was a

lot about Pinochet and Chairman Mao in there. That was

the only time I met him, and I was just a friend of a

friend. When I broke my back, he was in America. He came

to England to see me in the hospital and he said, "I

want to put you in the best hospital money can buy. I'll

take you anywhere and you won't have to worry about the

bill.' Isn't that amazing? It was Warren Beatty. Since

he's the kind of man who often gets unsympathetic press,

I just wanted to say there are some things about him that

he himself would never talk about.

MUSICIAN: If the music world is really so terrible,

why carry on?

NELSON: Musicians do complain about business and

the rest of it, but ... they're so damn lucky. Despite

all the threats of bankruptcy and all the angst, I wouldn't

change any of it, because I love what I'm doing and I

couldn't do it any other way. I've got a life that would

be a dream for some people, so there's very little room

to complain. And I'm bloody useless at anything else.

[laughs]

WYATT: My maths teacher at school told me once,

Look, if you don't pass maths 0-level, you'll be coming

back here, 'cause you won't get any work, you know.' And

I haven't had to go back to him yet. I've gone a long

way without any exam results - I must be well over halfway

by now. And I'm proud of that; it's pure vanity.

NELSON: That's like the day I left my day job.

The boss said, "Now, about this pop business, Bill...

[Laughter] it's rather flaky, you know. I don't want to

put you off or anything, I'm wishing you all the best,

but your job's always here for you if you have to come

back." I got outside that door and I went: ' Yeah!"

And I've never gone back. Not even to give them any autographs.

How to make a ROBERT WYATT record: Riviera portable keyboard

and make sure the vibrato's set real slow. "It matches

my voice," says Wyatt of the instrument that he found

in a Venice toyshop back In '73. Also in Wyatt's Louth

abode are a Yamaha baby grand piano and PSS-780 keyboard,

and two AKG D1200 E microphones. Percussives Include some

no-name timbales, Paiste crash, Black Rock Ride and an

old Gretsch snare which hasn't been used for a while.

"I never liked snares because of their martial overtones,

so I've gotten rid of them for my solo records."

He also favors brushes and mallets over sticks. Wyatt

gets it all down on a Tascam 244 four-track recorder,

hidden underneath the Kampuchean Flag.

And here's all you need to duplicate BILL NELSON's Studio

Rose-Croix in your very own home: a Fostex B16 tape machine,

A.H.B. Systems 8 32-channel mixing console, Sony PCM-Fl

mastering deck, Quad amp driving Tannoy Little Red Monitors,

and for outboard, a Yamaha SPX90, Fostex compressor/limiter,

and MXR 0/1 reverb. Keyboards include an E-max Series

1, Yamaha DX7 and CS70M, while the drum machine's an Akai

MPC 60. For guitars, Bill's got three Yamaha SG2000s,

Ovation 6 and 12 string acoustics, a Rickenbacker stereo

electric 12-string guitars, a Guild D50, and a custom-made

Viellette-Citron. A devoted E-Bow user, Nelson has one

of the original silver models.

Mac Randall

|