| |

|

|

Epiphanies - Wire N° 206 - April 2001 Epiphanies - Wire N° 206 - April 2001

EPIPHANIES

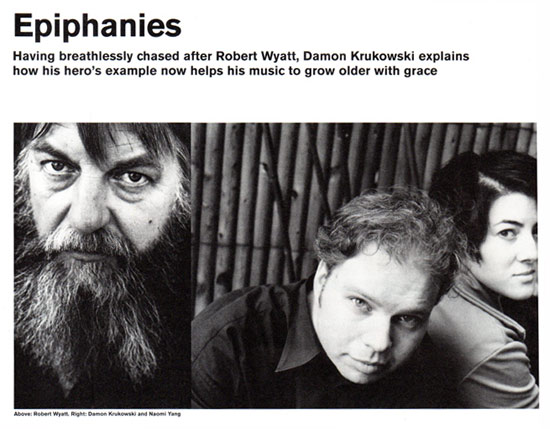

Having breathlessly chased after Robert Wyatt, Damon Krukowski explains how his hero's example now helps his music to grow older with grace

I think I officially crossed the boundary into obsessive fandom when I chased Robert Wyatt's wife Alfreda Benge down the street. This was in 1991, and my partner Naomi and I had been listening to Wyatt's 1974 record Rock Bottom in an endless loop - it was the only album that spoke to the simultaneous grief and joy we felt from music at the time. Robert Wyatt's voice entered my consciousness then in a way that made me feel I was hearing it internally, as if it would sound funny were I to hear it simply tape recorded. I had already been listening obsessively to his drumming for a few years, and similarly, as it were, from the wrong side of the kit: Soft Machine 1, 2, and Third; plus, a live bootleg I had found while on tour in Holland, Soft Machine Turns On (since released officially as Live At The Paradiso), had changed the way I saw the drums in front of me each day. What I heard initially in Robert Wyatt's drumming is similar in many ways to what I heard later in his melodies: a phrasing that flexes the boundaries of the bar without abandoning it. He is the 'free-est' drummer in rock because he finds freedom within its simple constraints. Like the great jazz musicians I know he admires, Robert Wyatt stretches and contracts time seemingly at will - and that, to my ears, communicates freedom more powerfully than even the wildest anarchic flailing.

No wonder, then, that Robert Wyatt has such a strong commitment to leftist politics: freedom, in music as in society, is a glorious gift that should be shared by all. His generosity fuels his playing, his politics and, as I have since learned, his dealings with obsessive fans. The incident when I chased Alfie down the street took place in London, outside the offices of the Rough Trade label, to which our former group Galaxie 500 had been signed.

Wyatt was also involved with the label at the time, and Naomi and I had arrived for a meeting just after Alfie had left hers. No sooner was her retreating form pointed out, than I raced out of the building after her. I didn't think first what I would say, and when I reached her I discovered I hadn't anything better to offer than, "Are you Alfie? l'm a huge fan of yours and Robert's!" - this delivered out of breath from my chase, no less. Her startled look brought me back to fan reality: the situation I had created for her was undoubtedly not a delightful one. I retreated hastily.

Years later, Naomi and I would meet both Alfie and Robert under better circumstances, though my heart was beating no less fast than during that encounter on the street. We had become labelmates once more, at Rykodisc UK (not a coincidence, exactly, since our music had each found a home there largely through the efforts of Andy Childs, who had previously worked at Rough Trade). But this time the folks at Ryko, knowing my obsession, deliberately arranged for me and Naomi to show up at the office just as Robert was taking a break from a round of press interviews. He and Alfie invited us to sit with them while they ate their Indian takeaway lunch, and they were so gracious, funny and warm - just the way I had imagined - that I once again had the strange sensation of experiencing the encounter as if it were a happy internal memory rather than an event in the external world. Later Naomi and I even tried to write a song about the experience, but it came out an awful maudlin mess. The feeling generated by meeting Robert and Alfie — joy — is one we don't seem to be able to translate successfully into a tune. We seem doomed to write songs only about much darker emotions.

Robert, on the other hand, has the facility to sing about

anything and everything and make it beautiful. His and Alfie lyrics can be deceptively mundane, describing a trip to Spain or the life cycle of a salmon, yet they can contain the germ of all feelings at once, like they say white contains all colours. The openness of their lyrics is not the blank generation's emptiness; it's a fullness of feeling expressed through details. Robert Wyatt may be the Chekhov of pop music.

He may also be our Billie Holiday. No one else in English language pop incorporates the expressiveness of jazz like Robert Wyatt. He sings a line as if it were unfolding before him, a landscape just coming into view. The surprise he generates in his melodies, an his phrasing of existing melodies, is something you can never get used to. I know Rock Bottom by heart, but that doesn't eliminate the jump it always has on me, the unexpected rhythmic and melodic turns that keep it surprising every time I hear it.

In my first age in music, Robert Wyatt taught me to look at my drum kit as an instrument rather than just something to hit; in my second age, he showed me what it might be to sing a meaningful tune; and I hope to learn from his example how to have a third age in music. Because Robert Wyatt, of all rock musicians, seems to know how to live with knowledge, and how to use it to improve his music. His latest album, 1997's Shleep, made a lot of people wake up and take notice, but they have all been great.

Uncompromised, and uncompromisingly lovely.

Damon & Naomi begin a UK tour in May with Ghost/White Heaven guitarist Kurihara, marking the release of their album Damon & Naon With Ghost. Their publishing imprint Exact Change has just published Give My Regards To Eighth Street: The Collected Writings Of Morton Feldman.

For info, see www.exactchange.com

|