| |

|

|

Captain Bob - The Word Issue 79 - September 2009 Captain Bob - The Word Issue 79 - September 2009

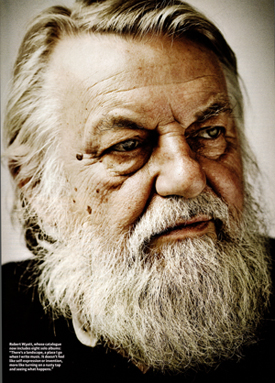

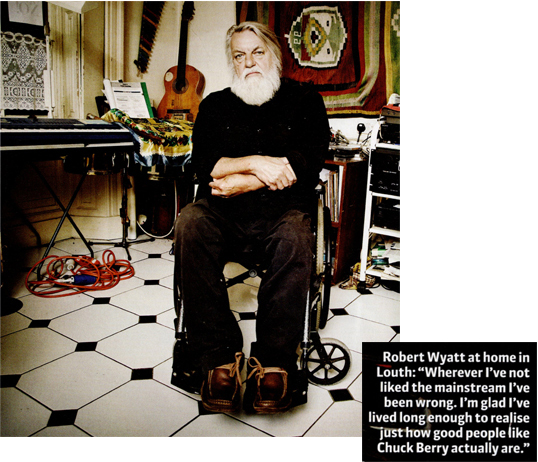

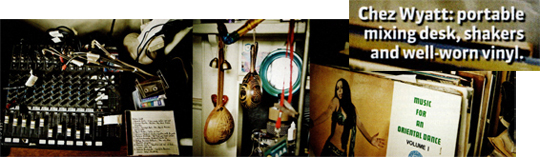

OBERT WYATT’S HOUSE IS RIGHT IN the middle of the Lincolnshire town of Louth, yet it's protected enough by its thick walls and beautifully tended garden to feel like it's in the middle of nowhere. It's only when I spot the tiny ceramic head - complete with a pair of glasses and a badge (Robin - The Boy Wonder!) - that sits almost unnoticed by the front door that I know for sure I have the right place. I can't imagine many other residents displaying a similar sense of the absurd. Inside the front door, just to the left, is Wyatt's studio. There's a crisply melodic jazz record playing, keyboards dotted around and a grand piano in the corner. A soft breeze rolls in from the road, rustling the curtains. Wyatt rolls down the corridor dressed all in black, his hair long and swept back, his beard trimmed and white as snow. Around him, every wall is covered with paintings - his wife Alfie is an artist and lyricist - and drawings and artworks. A cushion embroidered with the cover of his 1984 EP collection sits by the telephone. In the breakfast room there's a stack of vinyl under the CD player that I'm powerfully drawn to but never get to flick through as we move swiftly on to the garden where we sit around a big table under a cherry tree. Alfie's mother, Irena, who lived here too, died suddenly a few days ago and a huge bunch of white lilies has been placed on her favourite chair. OBERT WYATT’S HOUSE IS RIGHT IN the middle of the Lincolnshire town of Louth, yet it's protected enough by its thick walls and beautifully tended garden to feel like it's in the middle of nowhere. It's only when I spot the tiny ceramic head - complete with a pair of glasses and a badge (Robin - The Boy Wonder!) - that sits almost unnoticed by the front door that I know for sure I have the right place. I can't imagine many other residents displaying a similar sense of the absurd. Inside the front door, just to the left, is Wyatt's studio. There's a crisply melodic jazz record playing, keyboards dotted around and a grand piano in the corner. A soft breeze rolls in from the road, rustling the curtains. Wyatt rolls down the corridor dressed all in black, his hair long and swept back, his beard trimmed and white as snow. Around him, every wall is covered with paintings - his wife Alfie is an artist and lyricist - and drawings and artworks. A cushion embroidered with the cover of his 1984 EP collection sits by the telephone. In the breakfast room there's a stack of vinyl under the CD player that I'm powerfully drawn to but never get to flick through as we move swiftly on to the garden where we sit around a big table under a cherry tree. Alfie's mother, Irena, who lived here too, died suddenly a few days ago and a huge bunch of white lilies has been placed on her favourite chair.

"There's some of me that absolutely wishes I'd either had a lobotomy or not gone to bloody grammar school," Wyatt says, a cup of tea at his elbow. "Those schools are meant to be such great institutions, but I hated the whole experience. Provincial grammar-school boys are absurdly pretentious creatures. I've always tried to match up to the art that I loved, to get that into my music. Had it not been for that desire I would have very, very happily picked up from Eddie Cochran and Neil Sedaka and just done the very best, simplest pop songs I could. I love Ray Davies and Pete Townshend and I think if I could have not thought about it all so much I would have had a very happy life."

Wyatt loves a well-crafted popular song, so I ask if he can't write them or simply doesn't want to.

"Oh, I do try to make normal records," he says. "I get very crestfallen when people say, 'That's a lovely song, Robert, it's just not pop as we know it...'"

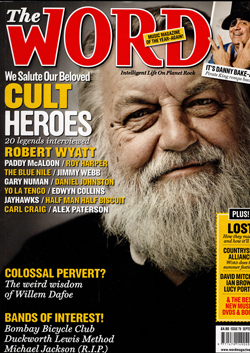

NOW 64, WYATT IS A TRUE CULT FIGURE, SOMEONE who stands for more than just the music he makes. His parents were interested in art and politics and music - "They had garlic and pasta and olive oil years before it was popular!" - and he grew up with the idea that art was something that would repay the time you invested in understanding it.

"I didn't understand modern jazz or modern art," he says, "but I was open to it all." The first music he loved was on his parents'78s of Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears ("He had a lovely light vibrato"); later he bunked off school to listen to Indian classical music and bebop. Music was always pointing the way forward.

"Ornette Coleman said there was no such thing as a wrong note," he laughs. "That really excited me! What was a wrong note? What would it sound like?"

Wyatt has been making his own music for the past 46 years, ever since he joined the Daevid Allen Trio in 1963. A year later he formed The Wilde Flowers with Kevin Ayers. In 1966 the two went on to form that most delicately prog of all prog legends, Soft Machine. Eighteen months later they were touring America with Jimi Hendrix.

"Oh God, that ridiculous late-'60s idea that there was 'progressive' music," he says now, half grinning, half frowning. "How stupid to think you could be better, more progressive than Haydn or Charlie Parker or John Lee Hooker. What twats these people were. There is no progression in music or art. There's change and different people being happy in different ways, but that's it."

In June 1973, aged 28, Wyatt fell from a third-floor window during a party for Gong's Gilli Smyth. He broke his back, meaning his career as a drummer was over (when he finds out the WORD photographer Sham is the same age, Wyatt immediately counsels him on staying on the ground floor at drunken parties), but a year later he recorded a performance of his hit version of The Monkees' I'm A Believer in his wheelchair and wearing what appears to be a denim dashiki for Top Of The Pops. Before it could be broadcast the footage was "lost" by the BBC and only found 30 years later.

"I wanted that record to make it plain that I wasn't part of any movement that thought it had grown out of pop music," he says.

Touring was over - his last major live appearance in London was recorded and finally released as Theatre Royal Drury Lane 8 September 1974 a full 31 years after it happened. The years in between have seen seven albums - and as many compilations - of Wyatt's songs, each one endlessly inventive and full of incredible, individual ideas about how rock and pop and jazz might have sounded if history had only worked out differently, been kinder or crueller. Though the records feature friends like Brian Eno, Phil Manzanera and Paul Weller, he works primarily at home, on his own.

"I find being in any specialist group a bit claustrophobic," he says. "But sitting around with musicians is better than sitting around with other people in wheelchairs talking about urinary problems. What's really happened is as I've physically retreated I've mentally gone out into the world, but I'm not broadminded musically, I plough a furrow the same as anybody does. Making the music is a lonely place, but even more so in a group than on your own. In a group you have to negotiate the traffic otherwise you'll crash, but if it's an empty road then you don't need to worry."

Do you know where this music comes from, I ask.

"Not really," he says, turning the now empty cup over in his hands. "It's doesn't feel like self-expression or invention. It's more like turning on a rusty tap and seeing what happens. But then you have to monitor it, editing what comes out until you don't wince when you hear it. You are on your own just as you are when you dream - you might meet people in your dreams but you can't get to them when you wake up. There is a landscape, a place I go, it's an aural landscape. There are harmonic skies of different hues, violet and green and blue. I hear harmonies like that and I see melodic lines as little sort of Giacometti, wiry things, drawings, but it's a living place, the whole place is alive and specific to me."

IT HAS BEEN 26 YEARS SINCE WYATT LAST TROUBLED the pop charts. Shipbuilding - later described by Elvis Costello as "the best lyrics I've ever written" - was a brilliant choice of song, a political folk piece given a jazz treatment, with this beautiful waver of a voice, this tremulous tenor, floating over the top. An Old Grey Whistle Test clip from 1983 shows Wyatt looking like Fidel Castro, his eyes pulled tight shut as he sings this "piece of completely escapist light entertainment". He has never rubbed up as close to the mainstream again.

"

"No!" he laughs. "But as a democrat I accept that people like stuff I don't like. I always used to think you can like what you like, but if you like Cliff Richard you're wrong - but not any more. I was completely wrong about that; I think he's a very nice man, a good guy and he's managed his career immaculately. I saw him at the Royal Command show with The Shadows [in December 2008] doing Move It and they were just terrific. I'm glad I've lived long enough to realise how good that stuff is. Same with Chuck Berry - I never liked him at all, but he's wonderful. Wherever I've not liked mainstream culture I've been wrong. I've learned that, on the whole, people are right - if they like something it's because it's good".

In 2001 Wyatt curated the Meltdown season at the Royal Festival Hall. Brett Anderson, Elvis Costello, The Residents and Gorky's Zygotic Mynci all appeared. This summer he was back on stage at his hero Ornette Coleman's own event. "Jazz is a magical idiom," he says. "It has

the visceral physicality of dance music, but it features people from other cultures let loose on European instruments - pianos, trumpets, trombones, saxophones - doing things with them they weren't designed to do. Fats Waller reinvented the piano. Louis Armstrong reinvented the trumpet. Jazz has this incredible richness..."

Meltdown is the perfect platform for someone like Wyatt, somewhere that every interest can be pursued. In the garden I mention how much I enjoyed the clip of him on stage with David Gilmour, reading Roger Waters' part from Comfortably Numb from a sheet of paper, like he'd never heard the song before. Gilmour looked delighted. "Ha! Well, David's free" Wyatt says. "He can do all the old hits, just not as we know them, but he does them. That works for him, he sees his history as a good thing, it gives him a secure base to go wherever he wants."

Would you have liked to have been in a huge band like his?

"I don't know," he says. "I'm glad the way things have worked out. I'm not on the road, so I can concentrate on new songs. I have time to work and I enjoy the freedom I have now, unencumbered by entourage and career structure."

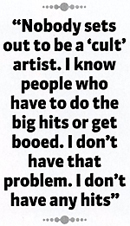

"Whatever it is they want," he says, "I'm very careful to try to thwart them at every step of the way. I don't want to be cornered. People say they can always tell my voice, so one day I'll release a record called something like The Lost Tapes Of East Van Solihull and I'll do a series of songs in other people's voices. I'll start with PJ Proby and move out from there. But nobody sets out to be a 'cult' artist - I certainly didn't. I know people who go on the road and if they don't do the big hits they get booed, and that must be terrible. I don't have that problem as I don't have any big hits, but that's OK. That's freed me up."

THE SUN HAS DROPPED AND THE TAXI TAKING US back to Market Rasen station sits idling outside. What is it that keeps you going, I ask as I pack up my bag.

"I suppose I always want another try at getting it right," he says, pulling on his white beard. "There are all these ideas left in the head - that's what keeps me going. I was brought up to think artists should behave badly because they were artists, but that's crap. Coltrane and Eric Dolphy behaved impeccably. I thought that behaving badly, getting drunk and being appalling and embarrassing was part of the licence that went with the musician's gig. Well, I was wrong and in my life I have had to learn first, then live. Even now there is lots of stuff I regret about how I am as a person, but, y'know, I'm not dead yet. There's still time to get it right."

A box-set of all nine Robert Wyatt albums plus his EPs is available now on Domino.

Story by Rob Fitzpatrick - Portrait by Shamil Tanna.

|