| |

|

|

The

Primer : Soft Machine - The Wire N° 232 - June 2003 The

Primer : Soft Machine - The Wire N° 232 - June 2003

THE PRIMER : SOFT MACHINE

|

Pre-Soft Machine incarnation

The Wilde Flowers on

stage in Canterbury, 1966

|

Common criticism of jazz-rock

argues that it pursued the worst excesses of each genre,

and caused irrevocable damage to both. Peter Schulze, who

produced many jazz-rock concerts for Radio Bremen in the

1970s, recalls that during this time many jazz groups incorporated

rock sensibilities, but far fewer rockers repaid the compliment.

The outstanding exception was Soft Machine. At the height

of their powers, this polymorphous British outfit achieved

a complete synthesis of rock and jazz by drawing not on

the excesses, but the strengths of both: raw energy, high

volume, intricate time signatures, exemplary musicianship,

expressive improvisation, gravitas and whimsy. To arrive

at such a successful amalgam required a rare mix of alchemy

and serendipity.

The journey starts in the early 1960s,

in Canterbury, Kent, where grammar school friends Robert

Wyatt, Hugh Hopper and Mike Ratledge bonded over a shared

passion for the bop and free jazz of Charles Mingus, Thelonious

Monk and Ornette Coleman. In early 1962 Wyatt befriended

Daevid Allen, an itinerant Australian guitarist and Beat

poetry aficionado. Allen became a mentor to the three friends,

inviting them to join him in London for an event at the

ICA performing free jazz and poetry in the company of Brion

Gysin and William S Burroughs. Soon after, Allen moved to

Paris to conduct tape experiments with Burroughs and the

then relatively unknown Terry Riley, among others. Back

in Canterbury, meanwhile, Ratledge left for Oxford to study

philosophy; and Wyatt and Hopper formed The Wilde Flowers

with Hopper's brother Brian, Pye Hastings, Richard and David

Sinclair, Richard Coughlan and Kevin Ayers. A few Voiceprint

compilations documenting the so-called Canterbury scene

quickly scotch the legend about it being the UK's Haight-Ashbury,

but they usefully reveal The Wilde Flowers as a not untypical

local group - bar the odd jolt of free jazz - playing R&B

and soul covers and originals. Allen eventually returned

to Canterbury with unknown American guitarist Larry Nolan

to rehearse with Ayers. The trio invited Ratledge, back

from Oxford, and Wyatt to join them, leaving the rest of

The Wilde Flowers to form Canterbury's other great mainstays,

Caravan.

When Nolan left as quickly as he came, they went out as

a quartet with Allen taking over on guitar, Wyatt on drums

and vocals, Ratledge on organ, and Ayers on bass and vocals.

After a mercifully brief spell playing out as Mr Head, in

mid-1966 they renamed themselves The Soft Machine, after

the Burroughs novel, with author's blessing. Although in

the beginning Soft Machine worked from a song base, it was

fed by two highly idiosyncratic writers in Ayers and Wyatt,

while their penchant for improvisation meant they were soon

taking their songs beyond the standard three minute pop

barrier. About the only place the group felt any sense of

belonging was in London's burgeoning psychedelic underground,

which in its pre-"Itchycoo Park" period was a

loose amalgam of heads open to all shades of weirdness.

Residencies at the UFO and Zebra clubs and extensive touring

in the UK followed until July 1966. Outside London's head

set, however, the group quickly ran into hostile, uncomprehending

audiences with little sympathy for the Soft Machine brand

of psychedelic revolution, which was founded on porous medleys

of songs and jams at excessive volume. In the summer of

1967, they temporarily quit the UK for dates in France,

only to lose guitarist Allen on their way back, when he

was refused UK entry as an undesirable alien.

Gong, pictured in 1971 in Hérouville, France,

with Kevin Ayers (2nd left) and Daevid Allen (centre)

|

|

Soft Machine touch down at the UFO Club, London, 1967 |

For the remainder of 1967, Soft Machine carried on as a

trio. In January 1968, they departed for San Francisco to

join Jimi Hendrix's US tour as support group. Before returning

home, Soft Machine recorded their first album at the Record

Plant Studios, New York. It was eventually released the

following year, but only in the USA. Before it came out,

Soft Machine had rejoined Hendrix for the winter leg of

his US tour. The punishing schedule left the group exhausted,

causing them to split up as soon as it was over. But with

a two-LP contract to honour, Wyatt and Ratledge were persuaded

to reform, recruiting Hugh Hopper on bass in place of Ayers,

who had disappeared somewhere in Spain. In 1969, they fulfilled

their contractual requirements by recording Soft Machine

Volume 2.

The chemistry of this Soft Machine trio, experimenting with

song segues and ever extending instrumental bridges at deafening

volume, triggered the chain reaction that caused the tectonic

plates of rock and jazz to shift, grate and collide. In

an incredibly fertile three year span between 1969-71, Soft

Machine concertina'd between three and seven members, as

the core trio experimented with a horn section involving

trumpeter Marc Charig, Elton Dean on alto sax and saxello,

Lyn Dobson on soprano and tenor and Nick Evans on trombone.

The horn section, minus Dobson, had been lifted piecemeal

from another pioneering jazz-rock outfit: Keith Tippett's

Sextet. Tippett was a jazz pianist who was already integrating

rock sensibilities seamlessly into his music. His sextet

had a fixed horn section, but employed the rhythm players

best suited to his music's fast-changing demands. Tippett's

bass pool included Jeff Clyne, Roy Babbington and Harry

Miller, and the drum seat was filled by Phil Howard, John

Marshall, Bryan Spring or Alan Jackson. Both Howard and

Marshall were destined to replace Wyatt in Soft Machine,

when the drumming vocalist was finally squeezed out of the

group he founded by an instrumental faction which thought

they were above or beyond mere songwriting. Babbington also

collaborated with The Softs, eventually replacing Hopper.

In the meantime, the impact of Miles Davis's Bitches Brew period on the rock world was sending ripples to British

shores, which was echoed in the electric jazz of lan Carr's

Nucleus, the third indispensable group of UK's great jazz-rock

experiment, featuring a rhythm section of Jeff Clyne and

John Marshall.

The music exploding out of this Soft Machine/Keith Tippett/Nucleus

triangle was a powerful, often astonishing rock-driven fusion

fired up on free impulses as it enthusiastically negotiated

jazz's trickier time signatures. Between them, they opened

up a space where the likes of Henry Cow crossfertilised

with their oppositional rock Improv; where Soft Machine

founder Daevid Allen located an audience for Gong's loopy

synths, busking saxes an space rock silliness; where The

Softs' Canterbury colleagues Caravan timidly raised the

hemline of their post-psychedelic Prog whimsy, if only for

a tantalising moment; where Hatfield And The North forged

a thrilling, if shortlived, fusion-tempered rock just before

the deluge of thrill-seeking second-string jazzers washed

the excitement out of the jazz-rock adventure. But these

are bit players of varying importance in this particular

story. Besides, most of its principal players managed to

engineer their own downfalls without any outside help. After

six albums Soft Machine had shaken out the last of its experimental

elements with the loss of bassist Hopper and reedsman Elton

Dean, whose playing kept the free flame burning through

The Softs' Third, Fourth and Fifth releases.

Ratledge, meanwhile, sulked his way through Seven and Bundles (1978), Soft Machine's first record for their new label

Harvest, and then quit the spotlight for a career in library

music, apparently. By the time Karl Jenkins took the helm,

Soft Machine had completely frittere away their earlier

phenomenal ability to orchestrate monumental blocks of fuzz

bass, organ and brass noise with wit and grace.

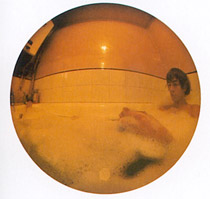

Soft

Machine (Kevin Ayers, Robert Wyatt, Mike Ratledge

and Daevid Allen) in Dulwich Park

|

With Jenkins doggedly running the franchise until 1981,

Soft Machine accelerated the erosion of the group's reputation

that had set in for real when Hopper left after Six.

But in truth, the damage had begun earlier. Indeed, some

argue it was seeded in the same impulses that drove them

to become one of the heaviest, most powerful and at times

pitiless innovative forces in any field at the dawn of the

70s. These peaks were attained at the great cost of Robert

Wyatt's vocals and humane Iyrics, not to mention his inspired

drumming. Fortunately, labels like Cuneiform, Voiceprint

and, latterly, Hux have unearthed a rich vein of archive

releases that attest to the group's astonishing power and

capacity for change between 1967-71.

It is no coincidence that all Soft Machine's early absconders

- Daevid Allen, Hugh Hopper, Elton Dean and Wyatt, both

with Matching Mole and solo - went on creating absorbing

music, while Jenkins made his mark on the charts in the

1990s with the execrable chill-out/Gregorian chant project

Adiemus (which, incidentally, credited Ratledge).

THE SOFT MACHINE

JET PROPELLED PHOTOGRAPHS

CHARLY SNAP133 CD 1967/1989

SOFT MACHINE TURNS ON VOL 1

VOICEPRINT VP231 CD 1967/2001

SOFT MACHINE TURNS ON VOL 2

VOICEPRINT VP234 CD 1967/2001

In April 1967, Soft Machine - here, Daevid Allen

on guitar, Kevin Ayers on bass and vocals, Mike Ratledge

on keyboards, and Robert Wyatt on drums and vocals - spent

three days in De Lane Lea Studios recording with producer,

impresario and entrepreneur Giorgio Gomelsky. Rumour has

it the group thought they were making music publishers'

demos, but Gomelsky insists they were there to record an

album and took the tapes away with him. Years after the

fact, these have disseminated under various different titles

and compilations, and here as Jet Propelled Photographs.

Its raw playing and sound quality argue that these were

indeed intended as demos, but there's no mistaking the potential

latent in the material, a good portion of it written when

Ayers and Wyatt were still in The Wilde Flowers. Whatever,

the group's unique approach to song stirs itself in early

versions of Ayers's "Shooting At The Moon" and

Hugh Hopper's "Memories" (later covered by Allen

on 1971's Banana Moon and Wyatt on the B side of his surprise

1974 hit "I'm A Believer"). Though he's basically

comping keyboard accompaniment, Ratledge's ear is finely

tuned to the nuances of Wyatt's falsetto, tracking mood

shifts as the vocal slithers between melancholy, heartbreak

and slapstick punning. But Allen's playing ranges from rudimentary

to just about competent. He has not yet evolved the shimmering

glissando - an echoing, spacey bottleneck technique he devised

after watching Syd Barrett - that distinguishes early Gong.

Complementing his own thin, resilient vocals, Wyatt's careering

drumming consolidates early Soft Machine's swinging proto-psychedelia.

The bootleg quality live recordings and studio demos constituting

the two volumes of Turns On confirm the early potential

of early Softs with and without Allen, but you have to listen

hard to hear it. You have to weigh the significance of their

handful of recordings from the Middle Earth club and elsewhere,

documenting the group's participation in London's psychedelic

underground, against the cruddy sound that renders it nigh

impossible to divine the ways they were expanding the psychedelic

bubble. Sadly, none of these sets include Soft Machine's

only single, "Love Makes Sweet Music" (by Kevin

Ayers), backed with "Reelin', Squealin', Dealin'"

and released on Polydor in 1967.

THE SOFT MACHINE

THE SOFT MACHINE

ONE WAY RECORDS MCAD22064 CD 1968

VOLUME 2

PROBE SPB1 002 CD 1969

To all intents and purposes, Soft

Machine's debut album was recorded live in the studio, with

'non-interfering' producers Chas Chandler and Tom Wilson.

But they weren't being jazz-purist about it, and when they

did indulge the odd studio intervention, such as a 'phased'

drum solo zapping between speakers like a stereo demonstration

record, they did so to glorious effect. Though they're still

song-orientated here, their tunes are as much vehicles for

the trio's dazzling instrumental interplay as vessels for

the lyrics.

Ratledge's organ is bursting with ebullient energy, while

Ayers has developed a keener balance of rebounding rhythm

and bass-led melodies in the absence of a guitarist. Wyatt,

meanwhile, is already incorporating 'found' lyrics and everyday

speech patterns in songs like "Why Am I So Short?".

But the highlights are "We Did it Again", an awesome

exercise in numbskull minimalism hobbled to a riff every

bit as compelling as The Kinks' "You Really Got Me"

and Velvet Underground's "What Goes On"; and Ayers's

mental wake-up call, "Why Are We Sleeping?"

With Ayers retired hurt after their two 1968 American tours,

Wyatt and Ratledge recruited bassplaying roadie Hugh Hopper

to make Volume 2. Now their sole vocalist, Wyatt is in fine

form throughout, scatting through " A Concise British

Alphabet" and his more complex wordgames. Ironically

plummy sleevenotes claim, "in general everybody's heads

are more together" and that the music "may impose

cerebral responsibilities on the listener".Too true.

The early Soft Machine sound is a minefield of contradictory

elements. Wyatt's drumming is magnificent from the outset:

confident, strident, polyrhythmically complex and refreshingly

unpredictable. And he's already a wonderfully enigmatic

singer, his expressive falsetto negotiating Iyrical passages

of intellectual realism, elegiac frailty and absurdist improvisation.

At this stage, Ratledge is the most technically advanced

player and his organ work is as concise as it is magisterial.

The departure of both Allen and Ayers had precipitated the

group's move into extended improvisation. Upon Hopper's

arrival this direction was sealed. With additional saxophone

input of Brian Hopper, Soft Machine were steadily moving

away from song qua song.

SOFT MACHINE

SPACED

CUNEIFORM RUNE90 CD 1969/1996

A fascinating digression more

than their next move, Spaced occupies a unique position

within The Softs' output. Resulting from an invitation to

produce music for artist Peter Dockley's 'living art installation'

at London's Roundhouse in early 1969, the group declined

to perform live (although they had famously accompanied

a Picasso play in the south of France a year or so earlier).

Instead they duly set about amassing prerecorded material

to cover for their non-happening at the happening, so to

speak. Brian Hopper was again drafted in to add a horn voice.

Rehearsed and recorded in an East London warehouse, the

finished soundtrack was constructed around loops and effects,

and cut together with engineer Bob Woolford using distinctly

Heath Robinson methods like looping tapes around milk bottles.

The ad hoc methodology produces a distinctive musique concrète

feel, with the resulting tonescapes anticipating the textures

of Ambient.

SOFT MACHINE

BBC RADIO 1967-1971

HUX HUX037 2XCD 2003

BACKWARDS

CUNEIFORM RUNE170 CD 1969/2002

Both these live compilations illuminate how Soft Machine

were far better live than in the recording studio, even

if the only audience actually present was a radio engineer.

Covering the eight sessions the group recorded for John

Peel's BBC Top Gear show, the Hux set spans every significant

incarnation of the group after Daevid Allen's departure,

including their septet experiments with an expanded brass

frontline borrowed from Keith Tippett. On Hux's evidence,

Peel and his producers had a knack for catching the group

on the cusp of change, and happily gave The Softs free rein.

Even though Wyatt ironically comments on the necessity of

shortening tracks to standard pop length in his amazing

stream of consciousness rendition of "Moon In June",

their song medleys mostly break the ten minute mark. Even

so, the group exercise remarkable economy in their Peel

contributions, making the Hux set a wonderful summary of

Soft Machine's growth from their 1967 summer of love to

the colder mausoleum monumentalism that prefigured Wyatt's

departure in 1971. Wyatt has commented how he got interested

in the idea of writing songs where the melody line followed

the pattern of everyday speech. Thus, in this legendary

version of "Moon In June, "I can still remember/The

last time we played on Top Gear/And though each little song/Was

less than three minutes long/Mike squeezed a solo in somehow/And

although we like our longer tunes/lt seems polite to cut

them down/To little bits/They might be hits/Who gives a...

after all. "

Backwards collates live material from various UK

and European dates, including some septet tracks from Paris

in November 1969, and a demo recording of "Moon In

June" by Wyatt solo. Its solitary nature evidences

Wyatt's increasing sense of alienation, as The Softs' power

base shifted.

THE KEITH

TIPPETT GROUP

YOU ARE HERE... I AM THERE

DISCONFORME DISC1963 CD 1969

DEDICATED TO YOU, BUT YOU WEREN'T

LlSTENING

AKARMA AK227 CD 1971

Pianist Keith Tippett's first

album unequivocally laid the ground rules for his particular

jazz-rock agenda. With all the material written by him,

the album has a satisfying continuity. More importantly,

this is composition of the highest order: measured and balanced

in his positioning of instruments to give maximum dynamic

effect. The pieces unravel slowly, with Tippett gradually

introducing rock-flavoured influences, while the playing

throughout is forthright and sometimes openly aggressive.

E Even at this early stage in Tippett's development, the

integrity of his thought process makes any reference to

specific forms superfluous, be they jazz or rock. The second

track "I Wish There Was A Nowhere" introduces a repeated

vamp over which Elton Dean weaves an accomplished alto solo,

while trumpeter Charig and trombonist Evans supply swelling

chordal overlays. Bassist Clyne and drummer Jackson build

a mesmeric pulse over the 14 minute duration of the composition.

If Tippett's debut album is impressive, ranging from fractured

avant gardism to pulsating repetition, Dedicated To You

is, quite simply, indispensable. The compositional credits

are more evenly dispersed here, with Evans, Dean, Hopper

and Charig aIl contributing. From the outset the album is

a rhythmic maelstrom, utilising drummers Wyatt, Phil Howard

and Bryan Spring as well as conga player Tony Uta. Spontaneous

joy is the result, with Charig and Evans in particularly

raucous mood, melding free jazz and rock sensibilities even

as they boil to the surface in a fierce bid for independence

from each other. Tippett's writing is so integrated, however,

that these competing elements are never allowed to rip the

piece apart. Instead, they generate a terrific and continuous

tension. "Thoughts To Geoff" illustrates this perfectly,

with Evans contributing explosive trombone, while Dean's

saxello solo on "Green And Orange Night Park" is worthy

of Roland Kirk. Tippett, meanwhile, ranges aIl over acoustic

and electric pianos to great effect.

SOFT MACHINE

THIRD

COLUMBIA 4714072 CD 1970

The third studio album is The Softs'

most complete statement of intent. It was originally released

in 1970 as a double LP, with a side each given over to Hopper's

"Facelift", Ratledge's "Slightly AIl The Time", Wyatt's

"Moon In June" and Ratledge's "Out-BloodyRageous". "Moon

In June" is pretty much a solo Wyatt recording, except for

Ratledge's fuzzily scrawled organ signature towards the

end. Wonderful as it is, it suffers in comparison with the

full group's inspired response to the same piece on the

Hux BBC Radio set. On Third, the absurdist element that

once defined Soft Machine's group character has been all

but ousted by the Ratledge-Hopper axis's heavily pedalled

emphasis on fuzzed-up jazz-rock with horn charts, with new

recruit Elton Dean's alto and saxello mostly displacing

Wyatt's vocalising. The sacrifice of his voice does not

preclude Wyatt bringing the relentless swinging energy and

invention of his drumming to Ratledge's and Hopper's splendid

side-Iong compositions. Recorded live at Birmingham's legendary

Mothers club and Croydon's Fairfield Hall, Hopper's "Facelift"

rises out of a circling electric piano rondo, until it's

abruptly halted by Ratledge's heavily fuzzed organ squalls.

Gradually Dean works up the courage to begin a conversation

for the whole quartet. The core of Ratledge's loveliest

composition, "Slightly AIl The Time", is Hopper's fabulous

walking bass part. The organist's other track, "Out-Bloody-Rageous",

bursts into being out of endlessly circling keyboards and

swooping sax squeals, with an augmented brass section pitching

precarious choruses between Dean's and Ratledge's grandstanding.

ROBERT WYATT

THE END OF AN EAR

COLUMBIA 4933422 CD 1970

Describing himself on the

sleeve as an "out of work pop singer", Wyatt was still Soft

Machine's drummer when he recorded this first solo statement

in 1970. Though it's a predominantly vocal album, with Wyatt

playing "drums, mouth, piano, organ", he's got anything

but pop on his mind. The album's two takes of Gil Evans's

"Las Vegas Tango Part One" are the closest he gets to actual

song. Otherwise the music centres on Wyatt's astonishing

montages of his multitracked vocal scatting. Mark Charig

and Elton Dean provide multitracked horn and sax treatments,

Mark Ellidge and Caravan's David Sinclair contribute piano

and organ, but the fascination here is the way Wyatt overdubs

his many discrete parts into an uneasy and frequently heartbreaking

interrogation of his role as a singer in a group that claims

to have outgrown the song.

SOFT MACHINE

NOISETTE

CUNEIFORM RUNE130 CD 1970/2000

FACELIFT

VOICEPRINT VP233 2XCD 1970/2001

Noisette is sourced from the same recording

of The Softs' January 1970 concert at Croydon Fairfield

Hall from which "Facelift" was partially lifted

for Third. Here they went out as a quintet, featuring

Lyn Dobson's soprano, fIute and vocals. At this stage, The

Softs were restlessly seeking new elements to keep themselves

fresh, and here the trio respond well to the evident empathy

already existing between Dobson and Dean.

When they returned to Croydon just three months later on

the Facelift double, they had already reverted to

their standard 1970 quartet. Captured on an audience recording

made by Hugh's brother Brian on a failing portable cassette

player, Facelift nevertheless offers today's listeners

an accurate impression of how the group must have sounded

from 'out front'. The music's so monstrously good, it's

almost terrifying. The quartet throw up stock repertoire

props, only with all the supports removed. The way they

race around shoring up these towering and teetering compositional

blocks with improvised bridges is astonishing. Soft Machine's

rehabilitated reputation is largely founded on this pair

of releases.

KEVIN AVERS

JOY OF A TOY

EMI 5827762 CD 1969

DAEVID ALLEN

BANANA MOON

CAROLINE C1512 CD 1971

These early solo albums by

two founder members underline how a long and happy life

in Soft Machine wasn't really on the cards for either of

them. On Ayers's irrepressible debut Joy Of A Toy,

the first of a great trilogy that included Shooting At

The Moon and Whatevershebringswesing, Wyatt drums

on most tracks and both Hugh Hopper and Mike Ratledge contribute;

but it's in no way a cloned Soft Machine album. Ayers's

songs are beautifully arranged throughout by pianist/composer

David Bedford, with Paul Buckminster on cello, Paul Minns

on oboe and Jeff Clyne on double bass. The album's hazily

surreal pastoralism veils Ayers's deeper interest in articulating

his Gurdjieff-inspired attempts to awaken humankind from

its slumber. Well, this was 1970 and Ayers wasn't the type

to take umbrage if everyone snoozed through the message.

For Shooting At The Moon, Ayers put together a ramshackle

improvising group to rattle the symmetry of the earlier

album's arrangements. His group The Whole World turned around

Bedford, Lol Coxhill on saxes and 'zoblophone', Mike Oldfield

on bass and guitar and Mick Fincher on drums. His earlier

jazz influence rears up in crudely effective see-sawing

rock improvisations to terrorise fans of his sweeter songs,

like the charming opener, "May I?".

Daevid Allen's solo debut Banana Moon is simpler

but no less inspired. Wyatt is again present on drums, and

by now Allen's lead guitar is a little more accomplished.

You can tell how far he's come by contrasting this album's

version of Hugh Hopper's of "Memories", also featuring

a poignant Wyatt vocal, with the same song on Jet Propelled

Photographs.

Now taking it at a slower pace, Allen brings out an

elegiac quality beyond the young, blushing Soft Machine's

reach. All the other songs are Allen's own.

SOFT MACHINE

FOURTH/FIFTH

COLUMBIA 4933412 CD 1971 & 1972

VIRTUALLY

CUNEIFORM RUNE100 CD 1971/1997

Fourth is Wyatt's last

outing with the group he founded and squired through their

difficult years. It's no coincidence that it is The Softs'

most overtly jazz album. You can put this down to Elton

Dean's growing influence, and it's his exuberant playing

that largely determines the character of the album, even

though he, like Ratledge, only contributes one composition,

compared with Hopper's pair: the side-Iong "Virtually"

suite and "Kings And Queens". Again, Charig, Evans and Hastings

fill in brass ensemble interjections, and this time they're

joined by the tenor sax of Alan Skidmore. If Fourth's

overall balance represents a step forward from Third,

with Ratledge's electric piano much in evidence, it's not

immediately clear exactly what they gained with that advance.

For all the brass frontline's free bluster, it's Hopper's

compositional Iyricism that shines through this album. Wyatt

might have been muted, but his drumming is simply sublime

throughout. Even so, the album's momentum is all but severed

from the group's psychedelic rock roots. For the first time,

The Softs sound less themselves and more like Keith Tippett's

group. Jazz now prevails.

Fifth is hinged around the two drummers who were

auditioned for Wyatt's vacant chair. Phil Howard and John

Marshall got a side each on the original vinyl LP, and the

music correspondingly vacillates between their opposing

styles. Roy Babbington is once again in evidence on double

bass. Howard is an incredibly exciting drummer with free

music propensities, who promised much in his shortlived

tenure. Sadly, he wastes his energies driving the group

into a free Improv corner that no one else particularly

wishes to inhabit. John Marshall, on the other hand, is

a more precise timekeeper. His side of Fifth is altogether

more disciplined and less spirited.

Virtually is a pristine recording from the vaults

of Radio Bremen that captures the classic Wyatt-Ratledge-Hopper-Dean

quartet in its final stages. It offers live renditions of

"Teeth", "Kings And Queens" and a truncated "Virtually".

More intriguing are the early versions of "All White" and

"Pigling Bland" (from Fifth), which suggest how that album

might have turned out had Wyatt stayed on. But by this point

the group's internal power struggles have resolved themselves

in Ratledge's favour, and though Wyatt sings, the set is

curiously introverted, as if the group are playing it as

a private rite of passage sounding an elegy for their own

doomed youth. Under the shadow of such composerly sobriety,

Dean's freeblowing tendency has also been brought in for

questioning.

ELTON DEAN

JUST US

CUNEIFORM RUNE103 CD 1971

He was ousted soon enough.

Dean's recently reissued solo debut provides clear evidence

of his indomitable free spirit. Here, the emphasis is on

fiery improvisation over Phil Howard's flailing polyrhythms

of a kind that no longer fitted Soft Machine's masterplan.

Dean augments his core trio of trumpeter Charig, bassist

Neville Whitehead and Howard with contributions from Mike

Ratledge and future Softs bassist Roy Babbington on two

tracks. Further, Just Us reprises Soft Machine's

"Neo-Caliban Grides" in a set otherwise spontaneously

'composed' in the studio. Relishing such spontaneity, his

playing throughout is exemplary.

NUCLEUS

ELASTIC ROCK/WE'LL TALK ABOUT IT LATER

BGO BGOCD47 CD 1970

THE PRETTY REDHEAD BBC SESSIONS

HUX HUX036 CD 1971-82/2003

LlVE IN BREMEN

CUNEIFORM RUNE173/174 CD 1971/2003

Trumpeter and Miles Davis

biographer lan Carr formed Nucleus with the intention of

electrifying jazz-rock, and Elastic Rock more than

fulfils his sonic vision. Carr's cool, muted trumpet and

mellow flugelhorn combine with the meandering soprano of

Karl Jenkins, who also plays electric piano to great effect,

and Brian Smith's tenor. Their unison playing is dramatically

offset by the tension created by guitarist Chris Spedding.

Driven by the outstanding rhythm section of Marshall and

Clyne, their impact is as immediate as rock.

Spedding's 'slack' style of elongating chords and phrases

made him a much sought-after session player, but he still

constituted part of the stable lineup that recorded its

successor the following year. We'll Talk About It Later

consolidates the group's pole position in jazz-rock. Nucleus's

approach to fusion is cooler than Soft Machine's, and their

more sophisticated arrangements are directed towards ensemble

unity. At this stage, that ambition doesn't inhibit their

ability to rock, however, and Spedding even adds a certain

funkiness. But it's Carr's clarion brass that directs Nucleus's

forward momentum, leaving Jenkins and Spedding to alternate

spiky interjections of guitar and electric piano behind

his and Smith's precision soloing.

Recorded in 1971 for BBC's Jazz London, Hux's radio

set reveals Nucleus weren't the kind of guys to let it all

hang out live. On the double Live In Bremen, Spedding

is replaced by guitarist Ray Russell for a set drawn from

their first three albums.

MATCHING MOLE

MATCHING MOLE

COLUMBIA 5054782 CD 1972

MATCHING MOLE'S LITTLE

RED RECORD

COLUMBIA COLM4714882 CD 1972

SMOKE SIGNALS

CUNEIFORM RUNE150 CD 2001

MARCH

CUNEIFORM RUNE172 CD 1972/2001

Matching Mole was a Robert Wyatt solo project until CBS

pressured him to form a group to promote it. Named by distorting

the French for 'Soft Machine' ('Machine Molle'), and made

up of old Canterbury mates David Sinclair (keyboards) and

Phil Miller (guitar), plus Bill MacCormick (bass), Matching

Mole weren't about to interfere with Wyatts original intention

to record "an album of love songs". Much of it

largely features his melancholy musings at the mellotron

he found in the studio. He stretches that instrument's lumbering

tonalities over skeletal piano to utterly disarming effect

on the poignant "O Caroline", where he steps out

of the frame to describe his new group in the act of recording

the broken love song he's now singing. Hemmed in with his

multitracked harmonies, the piano song "Signed Curtain"

finds him intoning "This is the first verse",

etc, as he slowly works his way through the template of

a pop song to the devastating last line, when he admits

to the futility of attempting to communicate his feelings

in words. Thereafter, Matching Mole quickly developed into

an erratically effective improvising group headed by guitarist

Phil Miller's relatively mood-sensitive "Part Of The

Dance".

Unhappy with Mole's change of direction, Sinclair jumped

ship, and was replaced by former Nucleus electric pianist

Dave MacRae on their second album, Little Red Record.

What with its daft skits and gooning satire framing tracks

as great as "God Song" and their increasingly

assured rock Improv, the album is as funny and inspired

as early Soft Machine.

Somewhat ironically, the two live CDs compiled from the

group's 1972 and 73 US and European tours reveal Wyatt's

increasing reluctance to sing. Now shaping up around McRae's

jamming vehicles, Matching Mole's rock Improv orientation

might well corroborate Wyatt's statement. "I was happiest

in Soft Machine when it was an all electric trio - after

that it wasn't quite my dream band anymore." Though

they strike a few sparks, whatever energy they muster is

sunk into the group's losing struggle with its growing sense

of entropy. Unsurprisingly, Wyatt

dissolved the group and was in the act of forming a third

line-up when he fell out of a window at a party, a tragedy

which left him permanently confined to a wheelchair. The

accident prompted Wyatt to embark on his ongoing quest to

construct one of contemporary music's most affecting and

idiosyncratic songbooks, on a string of releases which has

continued up to 1997's Shleep.

SOFT MACHINE

SIX

COLUMBIA 4949812 CD 1973

In keeping with their by now established ratio of

a major line-up change per album, on Six Elton Dean

has been replaced by Nucleus's Karl Jenkins. Originally

a double LP, Six has some very fine moments, but it's a

long way from the original group's sensibilities. A virtuoso

oboe player, Jenkins also plays baritone and soprano saxes

and electric piano. The first half of the album was recorded

live in Brighton and Guildford, with Ratledge and Jenkins

sharing composing honours with John Marshall's "5 From 13

(For Phil Seaman With Love & Thanks)". Unsurprisingly, given

the presence of Jenkins and Marshall, some tracks bear Nucleus's

hallmark accentuated rock riffing. On its original release, Six drew criticism that the group were now prone

to rambling, and that they had lost their essential spark.

Such remarks evidence a partial deafness to the careful

pattern building of the Marshall/Hopper rhythm section.

They consolidate these new compositions' reliance on overlapping

structures, which recall the systems musics of Philip Glass

and Steve Reich. Yet this quartet haven't entirely lost

their urge to improvise. They may no longer appeal to the

rock-biased contingent of Soft Machine's fanbase, but its

jazz aficionados go home satisfied. By this time, the numbers

were running out for Ratledge, The Softs' last surviving

original member. He shuffled and sulked through the desultory

Seven and Bundles and then quit.

KEITH TIPPETT'S

CENTIPEDE

SEPTOBER ENERGY

DISCONFORME DISC1965 CD 1971

The inspired insanity of Tippett's

Septober Energy is arguably the peak of the jazz-rock

collisions Soft Machine set in motion back in the mid-60s.

To realise the work, Tippett created the 50 piece organism

Centipede, whose sections move independently yet attain

unstoppable momentum and keen direction. Lord knows what

possessed him to assemble such a beast; it took a musician/producer

with the marshalling skills of Robert Fripp to help him

tame it on record. "When I formed Centipede," wrote Tippett,

"I wanted to enfold all the friends that I knew as much

as possible, from the classical world, to the jazz world,

the jazz-rock world, and the rock-rock world." Naturally,

it embraces all and none of these genres simultaneously.

HUGH HOPPER

1984

CUNEIFORM RUNE104 CD 1973

Hopper's first solo album

is a musical realisation of the visionary George Orwell

novel from which it takes its name. Partly responding to

The Softs becoming "a rather ordinary British jazz-rock

outfit", Hopper revisited his early 1960s tapeloop experiments

with Daevid Allen in Paris to recover his creative curiosity.

In the event, he adapted the tapeloop method itself as the

shaping metaphor of his musical realisation of the totalitarian

condition Orwell describes, interspersing darkly brilliant

loop pieces with short funk rock interludes that conjure

the exhilarating taste of freedom attained in the act of

resistance. These passages are delivered by a group including

John Marshall, Lol Coxhill and Nick Evans. Having tasted

freedom, Hopper soon made his escape from a group that now

frowned on uninhibited creativity.

|