| |

|

|

The

Wyatt Life - The Face N° 39 - July 1983 The

Wyatt Life - The Face N° 39 - July 1983

THE WYATT LIFE

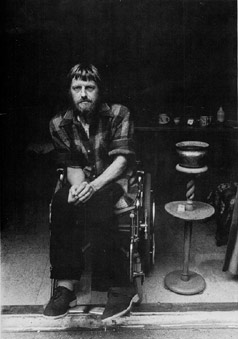

After many years

of critical neglect and seven months sunny exile on a Spanish

beach, Robert Wyatt is back in favour. With the Costellopenned

"Shipbuilding" firmly established in the charts

and the hearts of the nation, Anthony Denselow drew Wyatt

out of his introspective mood for some quiet thoughts on

global music, PLU's and the new life of a former "classic

Sixties drop-out figure"

Photo by Mike Laye

Robert Wyatt has tried many

different approaches

to his life and work. He has experimented with drink and

melancholic brooding, he has tried periods of relative working

normality when he has chatted openly to the press. He has

even tried tackling England from abroad. His most recent

approach seems to be a healthy combination of early introspection

and later career awareness.

He and his wife Alfie have now decided on the curious policy

of non recognition of PLU (people like us) which seems to

effectively mean that while he continues to seriously consider

his musical development he can hide out in Spain having

nothing whatsoever to do with the obscene worlds of media

and music business.

"It's not an act of hostility, in fact I'm quite grateful

to the music scene," says Wyatt. "It's more against

the kind of dreadful cultural narcissism that can occur

when like-minded people get together in a scene. I'm scared

of all the windows misting up and turning into mirrors."

In fact Wyatt's life has changed dramatically since he packed

up and headed for the Mediterranean seven months ago. He

had a single - "Shipbuilding" - bubbling so close

to the top 30 that only the FA cup replay postponed a Wyatt

airing on Top Of The Pops. He has suddenly become aware

of the growing following he's been attracting in recent

months and he has one of the year's finest albums as proof

of his importance in a music scene constantly drifting towards

the shallow end.

Wyatt sees himself as a "looker, watcher, selector

and editor" rather than as a live performer. The singles

that have been dribbling out on Rough Trade since the late

Seventies (collected on the new Wyatt album "Nothing

Can Stop Us" released recently for the second time)

are a truly oddball set of songs from staggeringly diverse

cultural contexts. The album is perhaps best described as

the first edition of Robert Wyatt's world view displaying

a total lack of concern with ego and fashion, rather a fascination

with world politics and the sort of universally powerful

music that can only lamely be described as folk.

There's a version of the Cuban national anthem updated to

talk about the presence American bases in Cuba that few

in the West know about. There's a song from Violetta Parra,

the Chilean responsible for getting that country's youth

song movement off the ground. "Her songs are straightforward,

unpolished, fragile and extraordinary," says Wyatt.

"This one's a helpless cry for Chileans to rise from

the grave and stand up for themselves."

There's Wyatt's heart-trembling version of Chic's "At

Last I Am Free", the typically child-like Ivor Cutler

song "Grass" ("Cutler says I sing it alright

except that I sing it as though it has meaning," reports

a surprised Wyatt); "Born Again Cretin" is inspired

by Nelson Mandela's imprisonment in South Africa; Billie

Holiday's "Strange Fruit" is about a racial lynching

in the American deep South while Wyatt's rendition of the

Red Flag speaks eloquently enough for itself.

"I suppose that I'm attracted to certain places but

it's more often just the tunes that get me first,"

says Wyatt about his material. "There are many musical

areas that I'm really into that I couldn't handle within

my technical range, things like Middle Eastern Arab music

and Oriental classical music. So this album doesn't reflect

all the styles that I'm interested in, just those that I

think I can add to."

|

|

Wyatt has also included work from

other people on the album. Along with Peter Blackman's rather

plodding poem about the battle of Stalingrad (revolutionary

in content, epic in style) is an excellent piece of music

from a British based Bengali troupe called Disharhi. Wyatt

heard them singing at an art against racism and fascism

concert and liked them so much he just asked them onto the

album. They sing (in Bengali) a trade union rallying song.

"I was accused of being elitist for not translating

the lyrics for the Parra and Disharhi songs," says

Wyatt. "It's not elitist if you're a Bengali is it?"

"Nothing Can Stop Us" is a generous album; a collection

of fine tunes, stimulating ideas and powerful emotions that

says much about the function and inspiration of music (as

it leaps between different cultural standpoints). Wyatt

himself is weary of giving the album too much significance.

"What we think of as global politics, global visions

and global cultures are in fact so conditioned by our Eurocentric

myopia that we still, despite our power and our increased

dealings with other people from around the world, haven't

come to terms with other cultures. I even make fun of attempting

to make a comprehensive world view with the title of the

album - which sounds quite revolutionary. It's a quote from

an American government official of the Thirties who reckoned

that America shouldn't make the same mistake as Britain

by trying to govern the world. He said America should simply

own it, nothing can stop us."

For its second outing to the record shops "Nothing

Can Stop Us" includes the Langer/Costello/Wyatt collaboration

"Shipbuilding", an intriguing partnership that

will hopefully bear more fruit in the future. Clive Langer,

apparently inspired by the way in which Wyatt sings the

Billie Holiday song "Strange Fruit", wrote the

music. Elvis Costello supplied the bleak lyrics and Wyatt

received the demo tape through the post one morning.

"It's been the happiest experience I've had as a producer/songwriter,"

says an unusually enthusiastic Elvis Costello of his encounter

with Wyatt. "The song has been realised perfectly.

It sounds completely like the intent of the lyric and melody,

Wyatt has an amazing voice. I'd always wanted to hear Dusty

Springfield record one of my songs and when she did 'Just

A Memory' it was a great bland disappointment. I think that

people have been so overwhelmed by the melancholy of Robert's

singing that the political comment in 'Shipbuilding' hasn't

been immediately spotted. The lyric seems to filter through

afterwards; the BBC probably wouldn't like it otherwise."

Wyatt seems to invest everything he sings with this

haunting sadness (it will be interesting to hear Costello's

version of "Shipbuilding" on his forthcoming album)

but he shies away from any boasts on his role as a singer.

"Maybe it's melancholic because I don't consciously

emote," he offers. "I'm aware that there are people

- musicians - who say that I'm an influence on them but

I really don't know enough about the current music scene.

In fact there's no one idiom available to me that I feel

comfortable with. Rock I find too musically dogmatic. I

was brought up on the sort of jazz with fluid, ambiguous,

drumming and walking bass lines and I guess it's that kind

of breezy fluidity that I'm trying to put into singing songs.

I still get infuriated with rigid blocks of verses and instrument

breaks, but I'm working on it."

Wyatt is sitting in his Twickenham flat (a quiet backwater

by the river that he still maintains despite the move to

Spain) surrounded by objects reflecting his preoccupations

in life. The walls of his brightly painted breakfast room

are covered with Alfie's equally bright paintings and with

ethnic art objects; the bookshelves are full of political,

mainly Communist, literature. He has a music room where

he can play piano (his toy organ has recently broken) and

bits of percussion. He has a specially built ramp so he

can run his wheelchair into the neat bird-haven garden.

The flat was bought for them partly by their friend Julie

Christie and from money raised by a charity concert given

by the Pink Floyd after Wyatt's tragic accident ten-years-ago

when he broke his spine falling from a house window. "I

didn't have to use all the money," recalls Wyatt, "because

the album 'Rock Bottom', which I still think is great, was

actually making me some money."

Given Wyatt's current popularity after years in the wilderness

it's incredible to consider that his first musical tangles

were back in the Sixties. As the drummer with Soft Machine

(he was then only a closet singer) he toured the US supporting

Jimi Hendrix, and built up quite a following in this country

("among the wrong sort of people") for his bare-backed

drumming enthusiasm.

The son of a psychologist father and journalist mother,

Wyatt was the perfect Sixties drop-out figure, the untrained

and illeducated intellectual member of a jazz-rock fusion

band. After Soft Machine disbanded in 1971 Wyatt started

to sing, first on the "End Of An Ear" album, then

with the band Matching Mole (recording that classic Wyatt

song "Caroline") and on the other solo albums

"Rock Bottom" and "Ruth Is Stranger Than

Richard". All these records are now difficult to obtain.

While the early albums often reflected Wyatt's frustration

with the traditional song format (another Matching Mole

song was actually about verses and choruses) he has steadily

developed the political quality of his songwriting and music

choice. Wyatt is a paid-up member of the Communist Party

and he feels that the CP helped him move away from the shock

of his accident and from the narcissism of rock in the mid

Seventies to a more considered philosophy.

|

|

"It helped me focus the jungle

of my thoughts, but it's difficult to talk about politics

and its relationship with music. I think Julie Burchill

is the only person I know of who can articulate that. I

don't think of music as intrinsically political (as some

do) but I think it's quite pretentious to claim that you're

not trying to say anything when you sing. All noise is communication

and reminds you of words. Personally I see the political

role of music in a totally different light. "Memories

Of You" for example (the B-side of 'Shipbuilding')

may sound just like a nostalgia song but it's political

for me because Eubie Blake who wrote it and who was 100

in 1983 was writing before jazz and somehow represents a

much used but amazingly uncredited strand of American popular

music. That he gets some royalties for that song is the

only genuinely quantifiable political act I can make: the

transfer of resources. Beyond that I have no control over

a song and how it affects anybody."

Wyatt's greatest joy in life is to take the phone off the

hook and tune his radio into a variety of exotic stations.

When he hits Radio Moscow, then he's off in dreamland. He

reads and listens to music from all over the world, especially

the early and obscure jazz that he grew up with, and recently

he has been expanding his fascination with all things Spanish.

Robert and Alfie live in "something bigger than

a garage" right on the beach south of Barcelona.

Alfie paints and Wyatt wheels himself around the beach,

writes, reads, attends regular weekend Catalan piss-ups,

and has been getting to hear as much pure Flamenco music

as possible. He is lucky that Barcelona has a good spinal

unit for he cannot stray away too far from medical surveillance.

"Being in a wheelchair has been like a short cut

to feeling old. You are forcibly removed from things like

sexual panic. You worry about getting in and out of places.

You start finding yourself sitting on park benches next

to retired couples. You feel more fixed, less nomadic.

You get tired quicker, and being a paraplegic, my body

is actually aging faster than most people's. You cannot

be spontaneous, you worry about the future and whether

people will buy your records. I never thought that ten

years ago."

Wyatt has again retreated back to Spain to consider his

next form of musical attack. Apart from the singles and

now one album, he has had little commercial output in

years and he says he could never consider performing live.

"I had to get drunk to do it before; it would mean

having things like managers and microphones." He

also made that excellent soundtrack for Victor Schonfeld's

horrifically distressing The Animals Film largely

because Julie Christie, the narrator, asked him to. He

worked furiously for months for £100. Talking Heads

demanded £500 just for the use of their music during

the opening sequence.

At the moment Wyatt is carefully observing the policy

of avoidance of PLU and he has yet to actually write a

song in Spain. Those of us who have been mesmerised by

Wyatt's dolorous singing will just have to wait. But hopefully

another album will not take another decade in coming.

"I can't do anything else in life declares stoically,

"I have to keep doing this somehow."

|