| |

|

|

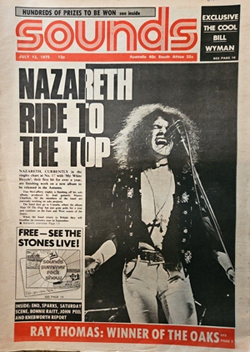

When In Rome... - Sounds - July 12, 1975 When In Rome... - Sounds - July 12, 1975

|

... you have to adjust to Italian politics, especially when you're putting on a free rock concert. Virgin chief Richard Branson found out the hard way when three of his group appeared at a Rome concert last weekend. STEVE PEACOCK is wise the event.

|

|

|

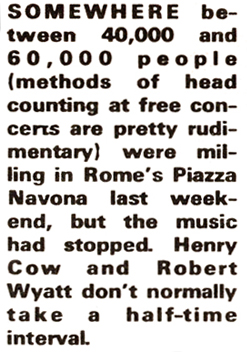

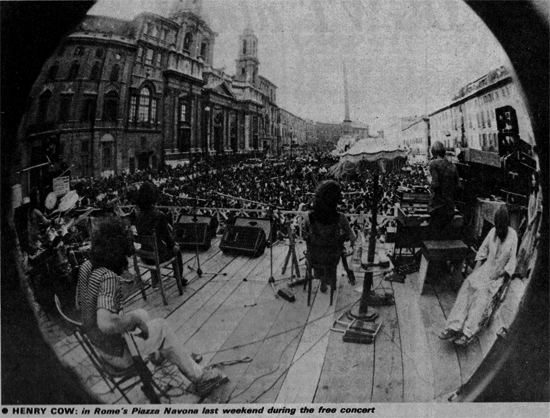

Somebody had trod on the power cable that stretched halfway across the square from the stage and pulled it out of its connection on the wall of a public building. (Methods of supplying electricity at free concerts can be pretty rudimentary as well.)

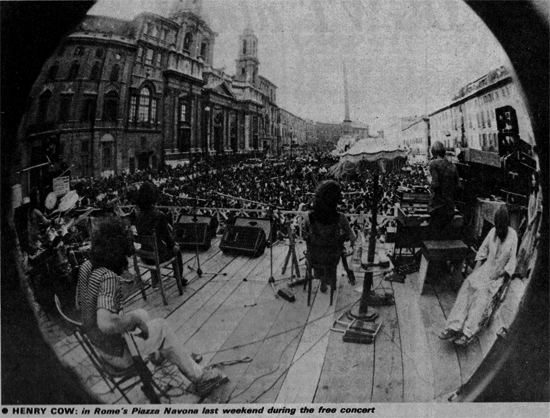

The power was reconnected, and the set was finished. Gong followed, and members of Gong and Henry Cow joined together for a finale. Virgin people, says chief Virgin Richard Branson, have long had a large and enthusiastic following in Italy. The crowd was large and the reception enthusiastic.

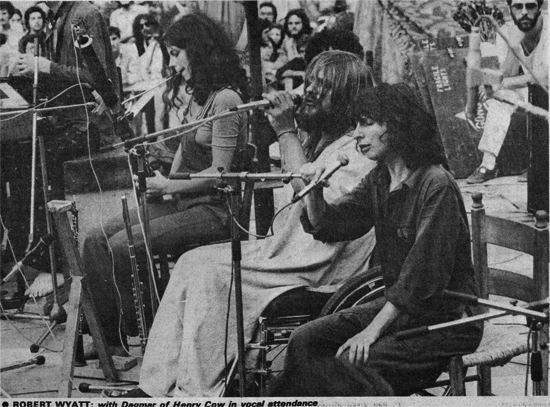

Graspers

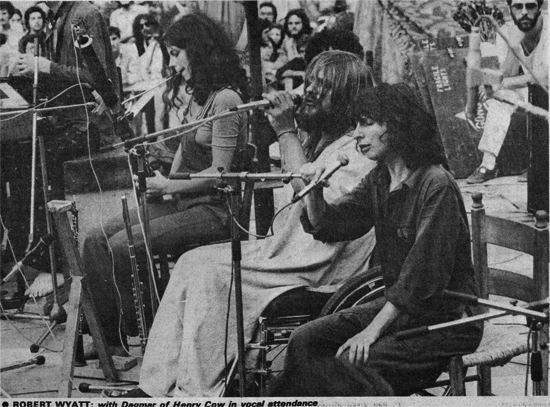

I enjoyed the Cow/Wyatt set, which was much the same as their recent New London Theatre concert but played with a mite less intensity. Robert was less than overjoyed, mainly because he couldn't hear himself sing. He didn't join the finale. I enjoyed Gong less, though more than I usually enjoy them. Since David Allen's retirement they have become more shaped, perhaps more formal. But Steve Hillage looked uncomfortable in the role of front man and they sounded more stylised than stylish. Their ovation was loud and warm. Italy has named one of her main music papers Gong, said Branson proudly. Another is called Muzak. After Mike Oldfield? He sighed - maybe he'd heard it before.

However, the critic in me was off-duty most of the time in Rome. The music played was important, but mostly for the fact that it was played at all. The last time Italy saw non-Italian bands on stage was in March when Lou Reed and String Driven Thing played Milan. Missiles were hurled at the performers, promoters were branded as opportunist graspers, robbing the people to line their own nests, and a fire hose was turned on the riot police.

The notion of music performed for no charge, so prevalent in Germany and France in recent years, resulted in Italian promoters shutting up shop (certainly as

far as international tours went). Rome's first major concert in a year was organised and partly financed by a coalition of the political Left and what it used to be acceptable to call the Underground. There was no charge to the consumers, but Richard Branson didn't exactly get in for nothing.

A COUPLE of months ago, a representative of the Left / Underground organisation Stampa Alternativa asked Virgin if they would be interested in supplying groups for a concert in Rome. In some senses it would be a test case (the Communist Party in Italy had approached Stampa's Ellio Donate to organise a series of concerts for them from September) and it would also be a celebration of Rome's continuing movement towards the left. Last month's gains for the Communists in regional elections all over the country emphasised that movement. Stampa raised about £1,000 towards the costs of the concert: Virgin agreed to provide the groups, and although the concert would be a co-promotion between Stampa and Muzak magazine, it would be underwritten by Virgin and its Italian licensee, Dischi Ricordi, to the tune of £1,500 each. The total cost would therefore be £4,000, which would cover the expenses, and pay what Richard Branson describes as "a small fee" to the musicians.

Idealism

At this point it might be an idea to underline some differences between Britain and Italy - particularly to explain the seemingly incongruous relationship between hippy/left idealism and a capitalist-dominated, often extraordinarily selfish rock business. In Britain, the idealism of the late Sixties appears to have faded into apathy inspired as much by idols with feet of clay and eyes on the tax havens as by direct opposition.

If there was ever any foundation for the idea that stamping your feet to rock bands as you waved a funny cigarette was a political act, it certainly ceases to have that implication when rock music and exotic cheroots are de rigueur at smart Hampstead dinner parties, and record company executives wear denims and keep a stash in the cocktail cabinet while they wheel and deal just like the boys in shiny suits.

Also the very idea of declaring yourself communist in a country run by what is, by European standards, a slightly right of-centre coalition in everything but name, where mild Lefties like Tony Benn are attacked as dangerous Commie firebrands, is enough to get you certified as loony, or merely laughed out of polite society.

|

Italy is different. Since the war, no political party has won a big enough share of the nation's vote to have an overall majority and the country has been governed by a coalition of centre parties, led by the Christian Democrats. The Communist party despite a large share of the vote, have been in opposition all the time. Whatever their share of the vote, they have not had a share in the Government.

That is still the position, but all the signs are that things must change soon. The first serious crack in the centre coalition's grasp on power came last year when the country voted against the Government's strongly-held beliefs and decided in favour of divorce - quite a radical step in a country which houses the Roman Catholic church's chief command post. Then, in last month's regional elections, the Communist party increased their share of the vote to become the strongest party in most of Italy's major cities. National elections aren't due until 1977 but the Left is now trying to force them forward.

The swing to the left has been dramatic: it is partly because of disenchantment with the ruling government and a reaction against its failures (high unemployment and inflation, inefficient social services, and so on), but there is another very important factor. The voting age has recently been lowered to 18. And we're back with rock music again.

A good percentage of the people who took up the jubilant chant "Roma E Rossa" outside the Communist Party headquarters in Rome's Piazza San Giovanni after the elections was probably also present among those who applauded Gong, Robert Wyatt and Henry Cow in the Piazza Navona last weekend. The apathy and cynicism which overtook Britain's underground / left / youth movements as the Sixties ended has not yet taken hold on Italy. Or perhaps radical ideas have taken on a new life. Certainly, it seems that a lot of the people who espouse radical politics in Italy are also those who listen to rock bands. And they are not people - who would take kindly to the British habit of accepting a role as Kids who are out to be Entertained with new Product. Hence the revolt against rock capitalism which stopped rock concerts for a year, and hence the banners under which rock music came back to Rome in the shape of a free concert last weekend.

|

Marijuana

NOW WE'RE doing the funky paradox: we left Richard Branson with a reasonable deal - a free concert, organised by the Left in defiance of capitalist promoters and associated business interests, but subsidised to the tune of £3,000 by capitalist record companies.

Virgin may demonstrate enlightened capitalism at work, but it is capitalism nonetheless. Dischi Ricordi is a large, independent Italian record company, also functioning as part of and in support of a capitalist economy. The irony of the situation seems unimportant as long as the compromise works. Rome gets the music free and presumably the record company gets its promotion and goodwill - or whatever. Just like Hyde Park, right?

Five minutes before Branson left to catch his flight to Rome, and some while after the groups had set out, a message arrives at Virgin from Dischi. It claims that Stampa Alternativa and Muzak are using the event to publicise causes with which Dischi does not wish to be associated - principally, a campaign to legalise marijuana in Italy. Dischi says it will not pay its share of the costs. Branson replies that it's too late to hack out now and boards his flight.

In Rome, he does his best to persuade Dischi Ricordi's executives to reconsider; to keep to their side of the bargain. He threatens to pull the bands out and effectively cancel the concert, but he knows quite well what he'll do if they still refuse. Virgin will pay their share as well, and Branson will return to London £3,000 lighter instead of the anticipated £1,500.

Justification

That's exactly what he had to do. The Italian record company remained adamant in its refusal to support the concert while it embraced the legalise marijuana slogan. Branson was angry, but admitted that Dischi had a point. The drugs thing was only part of it. Branson and Virgin happen to be in sympathy with that anyway, and once planned to organise a similar event in Britain.

What gave Dischi greater justification for pulling out was that the organisers appeared to be trying, to make political capital out of the event by disregarding the financial contribution the record companies were making. Speeches were made and leaflets were distributed in which it was claimed that the event proved that rock could flourish for free, without the help of capitalist businessmen. They implied that the cost of the concert had been covered by what the Left had raised and contributed.

Branson wasn't exactly thrilled with that one either, but he tried to persuade Dischi that, having promised the money in the first place, they should cough up and then hold a press conference to explain their side of it and point out that the concert needed the capitalist money to take place. He failed.

DOING THE funky paradox, part two: "I'll feel a bit silly going up there and singing 'Arise work men and seize the future' - they've already done it," mused Robert Wyatt. Not quite, they haven't.

|