| |

|

|

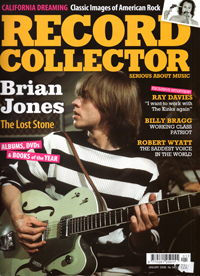

Wyatt City Blues - Record Collector N° 345 - January 2008 Wyatt City Blues - Record Collector N° 345 - January 2008

WYATT CITY BLUES

|

|

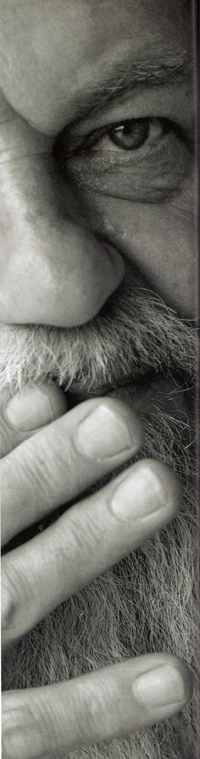

The Japanese musician Ryuichi Sakamoto once said that Robert Wyatt had "the saddest voice in the world". Yet although he has spent most of his career making records that have brought him little commercial success, Wyatt is one of our most fascinating and influential avant-garde artists, a unique innovator who has continued to blur the musical boundaries throughout a career that stretches back over 40 years.

|

|

|

|

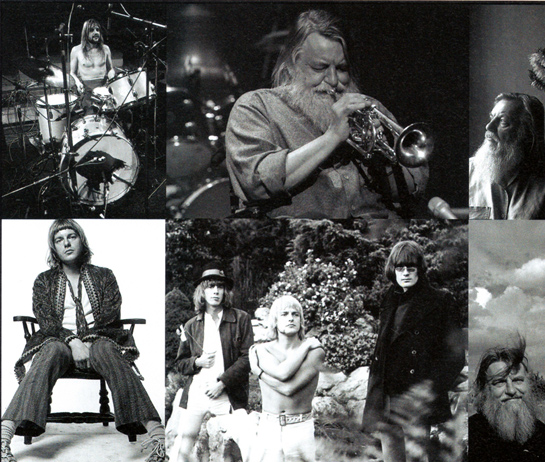

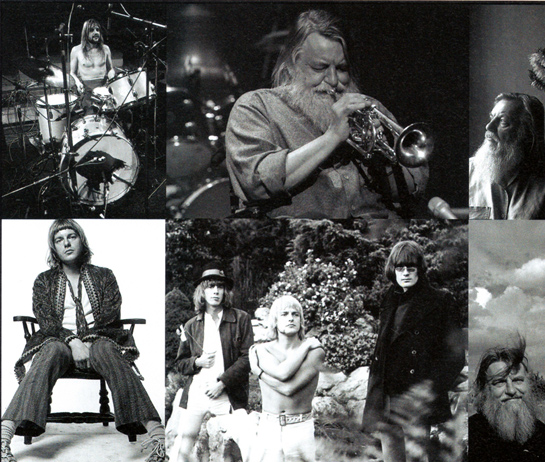

Robert Wyatt emerged as part of the 'Canterbury Scene' and started his career as the drummer and sometime singer with progressive jazzers Soft Machine, who took their name from the William Burroughs novel of the same name. They released their debut album in 1968 and spent most of the year touring with the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

Although he had released his first solo set in 1970, a year before the band's instrumental Fourth album, Wyatt had no intention of leaving the group. Having dominated the first two Soft Machine LPs, he found himself being left on the sidelines by the time it came to making their next two. After five years, Wyatt was fired from the band for reasons he still doesn't understand.

He wasted no time and formed the short-lived outfit Matching Mole, who made two albums before disbanding. While writing what was to become classic Rock Bottom LP, Robert Wyatt's life took a traumatic turn. In June 1973, drunk at a party, Wyatt fell from a fourth floor window and broke his leg and 12 vertebrae. He emerged permanently confined to a wheelchair.

He married poet and artist Alfreda Benge - aka Alfie - on the day Rock Bottom was released; she has provided lyrics and pictures for his album sleeves ever since. A year after the accident, Wyatt enjoyed the first of his two hit singles, an idiosyncratic reading of the Monkees' I'm A Believer. He is probably the only paraplegic singer, drummer, trumpet and keyboard player in the world with a record deal, and he is certainly the only one to have performed in his wheelchair on Top Of The Pops.

In 1975 Wyatt released his third set, Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard, and although he recorded a series of singles for Rough Trade in the early 80s (including his only other hit, an ineffably beautiful cover of Elvis Costello's Shipbuilding), he didn't put out another studio album until 1985's Old Rottenhat. He went on to records a series of groundbreaking records including Dondestan, Shleep and his last L.P, Cukooland, which earned Wyatt more mainstream attention than any of his previous albums and featured illustrious guests such as Paul Weller, Phil Manzanera, David Gilmour and Brian Eno.

Wyatt's new set, Comicopera, is an astonishing 16-song concept album in three acts. Much like most of his work, it is not what you would call a jazz alb that could only have been created by a jazz man.

Recorded at Wyatt's house in Louth and at Manzanera's Gallery Studio, Comicopera again features Weller, Manzanera and Eno alongside a crack horn session that includes Annie Whitehead and Gilad Atzmon.

Although Wyatt has suffered from periodic bouts of depression throughout his life, he is in fine form when we meet in the member's bar on the top floor of the recently refurbished Festival Hall on a muggy autumn morning. Having declined his

publicist's offer of a pre-interview breakfast ("Alfie nicked a couple of croissants from the hotel for me to have on the journey here"), Wyatt is fizzing with so much enthusiasm that he doesn't stop talking for over two hours.

Comicopera sounds very different to your last few albums.

Well, I try not to repeat myself, but although the voice is the same old thing, it gets lower and lower, and as I sink into the abyss, I grab out for other musicians and singers to help me do the high notes. Over the last 30 years, I've probably lost about an octave at the top and added one at the bottom. It's old age...that and the fags.

Can you take us through Comicopera's three sections?

The first third seems to fall into relationship stuff, man and woman losing each other, foggy things that happen between people and attempts at love between people where it's quite hard for one reason or another. The second bit leaves that kind of enclosed space, and it's just me pottering about England, which I see as a kind of rather scrappy, unkempt Methodist chapel. It's not that I sit there deliberating, choosing metaphors; it just seems to come out like that. But there's merriment in there in the second bit. I like comedy myself.

When I was in the studio with Monica Vasconcelos - who sings on Just As You Are — she said "You're so playful in the studio." And that's the nicest thing anybody has ever said about me. I just really like having fun. I hate to say this joke, but deep down, I'm shallow. It sort of sums it up, really. It's a bit like Ivor [Cutler]; deep down he was utterly trivial, just a sort of childish joke thing, but the legacy of being Jewish and the tragedy of his people sat with him very uneasily, and it was almost like carrying a great weight. My great weight is English-speaking people, the Empire.

Does that weigh heavily on you? It really does, and as an artist, I feel un-entertained by it. There are people who are poor and old fashioned, but they always seem to wear fantastic clothes and cook fantastic food. The further Western civilisation has gone, they get Anglicised and they go around wearing horrible sports clothes, eating hamburgers and getting fat watching fucking Britney Spears on telly.

For hundreds of years, I think we have absolutely lowered the tone of every neighbourhood we've gone into, and we think we're elevating. I just feel ashamed and offended at what my tax money is being spent on. For example, we're being told to

watch our carbon footprint. How much carbon footprint does the average bombing raid on Basra use up compared with me and my refuse? Fuck off.

|

There are two particularly moving songs that address the situation, told from the perspective of the person doing the bombing and the person being bombed.

The narrator actually shifts. At the end of the second section I'm both the euphoric bomber (A Beautiful War), and the apoplectic bombed person (Out Of The Blue). It shifts about in a way that I haven't consciously done in the past.

The third section sees a shift from songs in English to Italian and Spanish. Did you decide not to sing in English as a protest against the war in Iraq?

Sort of. After the bombing it's to do with feeling completely alienated from Anglo-American culture, just sort of being silent as an English-speaking person because of this fucking war. Now I'm in my 60s, I know I'm never gonna see a world in which the English-speaking people are not thumping round the world telling Johnny Foreigner what to do, and that did hit me with a sort of thud. The last thing I sing in English is: "You've planted all your everlasting hatred in my heart."

Do you find it difficult articulating these quite complex political issues in your music without feeling a little clumsy?

I do find it difficult, because clumsy and diatribal aren't

things I want to be. In fact, I really don't think what I sing makes any difference anyway, because I know enough about politics to know that politics is just about power, guns and money. I just don't think politics is about artists. I wouldn't trust most of us as far as you could throw us anyway. Artists are like cheerleaders at a football match; you can scream "Arsenal" until your head falls off, but it won't get them another goal. I'm mostly concerned with making a really nice sounding record and how to have a little fun in the studio. I'd be happy not to write about this stuff, it's just these are the things that come to the surface. I'd much rather live in a kinder world or one where I was ignorant to it. Matisse never addressed the issues in the world around him, but Picasso did. They're both great painters, it's just how it worked for them.

Are you still a card-carrying communist?

No, because there is no such thing as a communist. It's like saying are you still Yugoslavian? The thing I probably feel most affectionate about is the old left-wing revolutionary romantic sort of moments which caught my imagination in the 70s and 80s. As anachronistic as that is, it's probably even more deeply imbedded in me than all the art and music stuff. It's stayed with me, and it means a lot to me.

Were you conscious of trying to capture the sound of a band playing together in a room for this album?

Yes, it's like a fantasy band, and even though that band could not exist, it does exist for a couple of weeks when we're making the record. Everything the musicians play is fairly spontaneous. We're not playing together in the studio, because I actually work with musicians individually and then put it all together layer by layer afterwards.

Did you miss being in a band after Soft Machine?

Well, I never missed being in a group after them, I missed being in a group after Matching Mole. That was a very merry little band, although we only made a couple of LPs and then I fell out of a window before the third. It never settled, really, but then to be fair to the others, I don't think any band I was with ever could have settled.

I just can't imagine a group which could do all the different things that there are to do, which is why I prefer the way I work now, which is to get appropriate people for each particular project. On the second track on this record, it's me with Yaron Stavi doing most of it along with Paul Weller on guitar and Monica and me doing the vocals. Well, that particular group isn't appropriate to do any other song on the record.

Would you say you are still learning at this stage in your career?

I think age is nothing but a good thing, because I just keep on learning stuff and working out how to do things. It's just a continuous, bigger, better, brighter world for me in terms of working musically. I can't believe I get to do this stuff, and I've now got the courage to ask these musicians to do things and then they do other stuff beyond it. What I like from the best jazz is the fact that the colours aren't just an instrument, they're the person who plays it. So it's not just a tenor sax or trombone, it's Gilad Atzmon and Annie Whitehead.

Can you take us through your writing process?

It varies. On the whole, I just fiddle around with chords on the keyboard and then if I've got a chord shift that can be quite arresting, I'll just record it and then keep working on it or put it away. I don't even sit down and try to do it, I just have to get things out and write things down. My room is a mess of bits of paper and notebooks with comments and drawings and observations, some of which turn into words for songs. The reason I don't write many songs is because the words don't often match the music, unless you sort of lever it in; I don't like doing that. I like to find a phrase that just sits on to the tune like it was made for it.

In the past, you have compared the way you write to an animal hunting.

That's right, just snuffling about, and if it smells good, I'll go towards it. I do that with chords and with words. I honestly have no idea what it means, I'm just drawn along by my nose. The only trouble with interviews is that it sounds like everything is the result of some kind of intellectual deliberation, whereas the deliberation and analysis comes afterwards and before, but not while I'm doing it. I work entirely by instinct.

Do you spend most of your time thinking about music?

I don't know about that. I don't think about music in terms of me making it, but I am very interested in it, and I listen to acres of music every day. My record collection goes from around the time I was born right through to about Coltrane dying, which is also, funnily enough, about the time I started making money when playing in London in '67, when all us boy-next-door types started to get into pop groups and rock groups. It's all very merry, but it ain't Coltrane.

How do you look back on those times now?

I think of those times as just murky and uncomfortable and lonely, always being the wrong person in the wrong place with the wrong people. It's just a very uncomfortable period for me, the late 60s. I tend not to think about that period very much. I go into the tunnel sort of around then, and I come out around '73 with Alfie, working towards Rock Bottom. Then I can sort of pick up the pieces from there.

Coming out of that live-fast-die-young era of the 60s, did you expect to die before you reached middle age? Oh yeah, absolutely. I actually attempted suicide when I was 16, not out of sadness, but because I'd sort of had enough already. I just watched what grown-ups did and I thought - I'm not sure I could ever be bothered to do any of that. Indeed, I haven't bothered to do much of it. At that very moment, the eternal infantilism of rock music suddenly presented itself to me, and I could be a kid for the rest of my bloody life, and here I still am. It does surprise me that I've lived this long, because I'm very careless really. I'm not interested in health or anything. |

| |

"How much carbon footprint does

the average bombing raid use up

compared with me and my refuse?

F * * * o f f . " |

|

Would you say you have suffered from long bouts of depression throughout your life? Yes, I have done and still do. I don't know what the word means, but if "I really wish I was dead and had never been born" is depressed, then yes. I like life, but I cannot imagine thinking - Oh, it's great to be alive. I just think life is something you've got to get through. I envy the dead, quite honestly. It's not that I'm tragic, I just find it very hard.

Meanwhile, the best substitute for death is sleep, which I love greatly. Nod off and you don't have to respond to anything. I never want to do anything apart from dream, and Alfie makes it pretty easy for me to live like that, so I'm quite happy. In fact, I've never been better than I am now.

Do you see your music as a sort of collage?

Yes, that's exactly how it works. I just keep doing it, add bits and tear bits off. That's one thing that's easier than painting, 'cos if you've painted all the layers of paint on, it's hard to peel them off again; in the studio you can put down layers and layers of instruments and just start stripping them off in different orders to see what's left.

Do you generally prefer the music you're making now to your earlier work?

On the whole, yes, but on the other hand, sometimes I'm taken by surprise if somebody plays me something I did years ago that I'd forgotten. Sometimes I've just been a guest on some little project I've forgotten, and I've had to come up with something that I wouldn't have come up with on my own, and that's really nice.

Would you say Comicopera harks back to your political albums of the 70s and 80s?

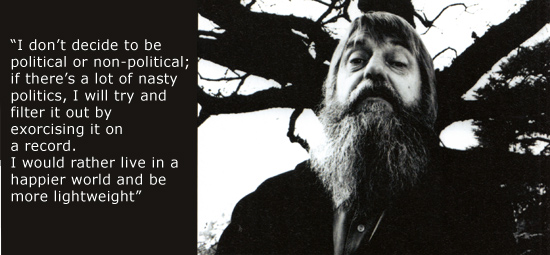

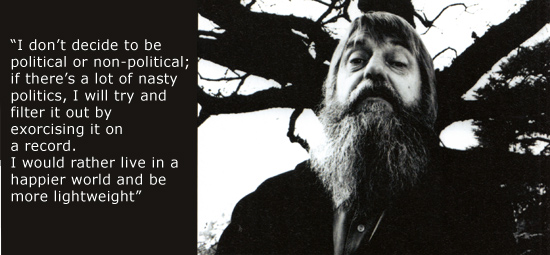

It seems to, but that's simply a response to the times we live in. I don't decide to be political or non-political; if there's a lot of nasty politics, I will try and filter it out by exorcising it on a record. I would rather live in a happier world and be more lightweight in response, but there's still a war on right now, we are part of it, and the tug of that affects everything I do. I live in this world, so that's how it comes out on the record. But it's the old cliché - us blondes just wanna have fun. I'm no different you know. I've always aspired that way, but I've just got to face reality, 'cause it's never gonna happen, is it?

Do you find it harder to write as you get older? It's the same really. It's sporadic. I do write all the time anyway, so it's just a question of whether anything I come up with is appropriate for what I do. There's a lot of stuff that goes on in my life outside music. I've got a son and a daughter, they've got children, I've got Alfie, and we've got her mother living at our house. We're having a life, if shopping and washing potatoes is having a life. I don't just sit there being an artist. I love peeling potatoes and going to the shops. I don't often have long periods where I'm not working on any music at all, but I don't want to give the impression that I'm a particularly useful domestic animal... I'm not that either.

How do you look back on the time you spent with Jimi Hendrix?

I think of him with nothing but love, affection and admiration. I was just very lucky to have been there. Rock musicians can be a terribly arrogant, bolshy lot, but Hendrix was always a grown-up and a real gent who never threw his weight around. He was always riveting on stage, but he wasn't always on top of it and he'd sometimes get a bit lost. We saw him nearly every night for a year throughout 1968, but I was there as another musician playing a concert that evening, so I can't say I was concentrating on Hendrix every night. I don't particularly like rock music, and I always felt most rock bands were a bit bombastic for me, but there was a fluidity about what Hendrix did which I really liked.

What do you think makes Rock Bottom and Ruth is Stranger Than Richard so timeless?

I don't know, maybe it was the fact that I had to invent a whole new way of doing music. Necessity is the mother of invention... I'd worked in a group before, and I had

to work out a new way of making music, the way I made it on those records. I couldn't really use much of what I'd learned before, so I had to come up with something new, so maybe those albums have got some of that fresh angle and that feel.

Most of the music that I like certainly doesn't come and go with the traffic of the day. I mean, the whole point about art really is that it's something that lives beyond the moment that it was created. A caveman makes a mark on a cave wall, something that will be there the next morning. Art is about making a mark.

|

Would you say that music is a less important force than it was?

I really couldn't care less. I've got a job doing it, but in terms of how the business suffers or doesn't suffer in the current climate, it just doesn't matter to me.

But the music business is so fast moving; don't you think you have to ask yourself where the next Charlie Parker is going to come from?

Well, l'm still quite happy with the fîrst one, thank you. l'm more concerned not to lose his memory in an age of novelty, so I don't want the Charlie Parkers of this world to get buried under great heaps and racks full of the latest thing.

Which artists have had the biggest influence on you?

Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus, Ray Charles and Dionne Warwick. Individually, there's nothing I can do that gets anywhere near Charlie Parker in terms of a sequence of notes, but I mention Ellington and Mingus because they're about the organisation of more than one person into a sound picture — how to make a bunch of notes and different colours like an organic whole swirling along together. It's such a valuable thing to me, and I don't think any other form of music has ever quite been able to do that.

How do you look back on the music you made with Soft Machine?

It's difficult to say because when I was thrown out of the band, I threw every single Soft Machine record into the dustbin, and I never listened to them again. If I am forced to think about it, I try and tell myself it wasn't a complete waste of time, and that interesting things happened and that young men can survive anything.

There is some good music there, and I suppose it's all part of an apprenticeship, my equivalent of doing National Service or something like that... it builds your muscles up and teaches you stuff about how to live in the grown-up world if you eventually get there.

Do you still feel bitter about the whole thing?

Well, I do think it's a bit cheeky that I didn't get any money, so we had to struggle with nothing to try and make ends meet. It still makes me very angry how I got treated by the record company, the manager and the group. People say that all musicians get exploited by managers, but musicians can be just as bad. It was interesting music, but I also learned that for a human life, interesting isn't enough in art. When art works best, it's about a moment of human contact on a lonely planet, and it's not just a question of being impressed by cleverness and brilliant ideas.

Everybody feels this stuff. I don't feel any more than anyone else and I'm no deeper than anyone else, so my job is simply to get a craft which channels it and lets it out in a sort of clear way that other people can latch on to. So in that sense, my job is only technical, because people do the emotional stuff themselves when they listen. Everybody's got heart, otherwise it wouldn't work.

Is the idea of your musical legacy important to you?

It's a nice idea, but it's a bit grand. I see it more as constant attempts to get it right from a different angle, just to get an hour of music that I can put on without getting bored and without wincing. It's not a question of trying to make a masterpiece, it's much less than that; it's just a question of damage limitation, endlessly trying to make a record without the mistakes on it.

Having barely paused for breath during our time together, Wyatt is shattered and in desperate need of a cigarette. As he weaves his wheelchair past the hordes of people in the foyer at breakneck speed, nearly knocking over a table or two along the way, he suddenly comes to a halt and points up excitedly at the sign above the Festival Hall doors. "Way Out," exclaims Robert Wyatt with a boyish grin. "Two of my favourite words."

Comicopera is out now on Domino

|