| |

|

|

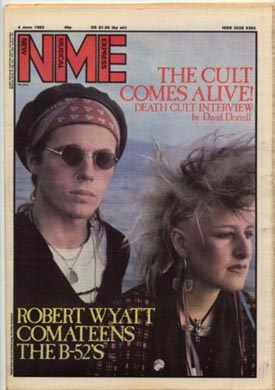

Robert Wyatt - When the Boat comes in - New Musical Express - 4th June,

1983 Robert Wyatt - When the Boat comes in - New Musical Express - 4th June,

1983

|

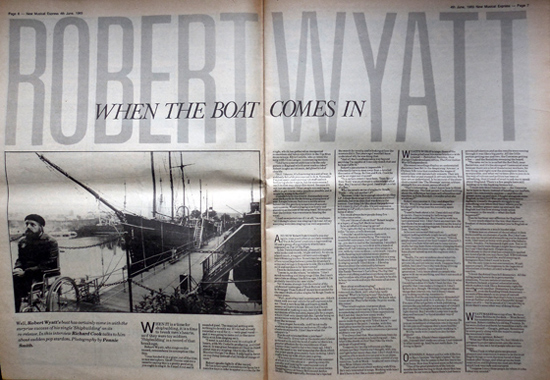

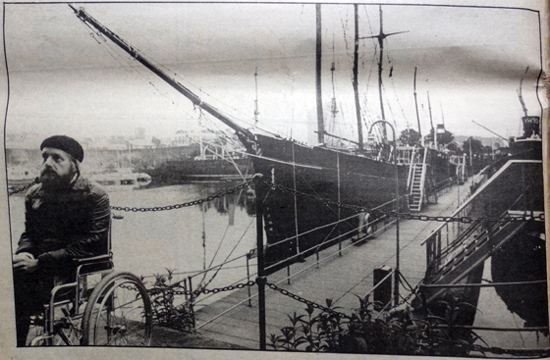

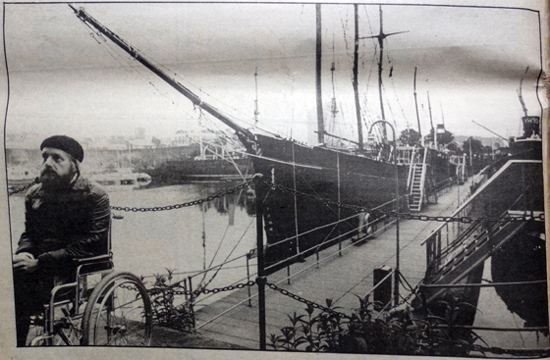

Well, Robert Wyatt's boat has certainly come in with the surprise success of his single 'Shipbuilding' on its re-release. In this interview Richard Cook talks to him about sudden pop stardom.

Photography by Pennie Smith.

WHEN IT is a time for shipbuilding, it is a time to break men's hearts, as if they were toy soldiers. 'Shipbuilding' is a record of that breakage.

Robert Wyatt, who sings on the record, remembers its conception like this.

"I was handed it on a plate, out of the blue, to mix metaphors. Geoff (Travis) sent me a cassette saying this is a pretty good song, you ought to sing it. So I tried it out and it sounded good. The musical setting was nothing to do with me. Elvis had already recorded a vocal for it – very good vocal – and it was going to come out in the same form with him singing on it.

"I went in and did a vocal in a couple of hours, with Mr Costello producing, and that was it. It was great because all I had to think about was my singing, like on the Mike Mantler things I've done. I only had to focus on one thing instead of all kinds of things at once."

Robert speaks lightly of the record. He has interrupted his residence in Spain for a mere few days in order to appear in a video for the single, which has gathered an unexpected momentum and taken a position in the Top 30 on its re-release. Elvis Costello, who co-wrote the song with Clive Langer, is overseeing matters.

"I did have a secret ambition to be the only person in England who'd never made a video!" Robert laughs an intimate, delighted kind of chuckle.

"Still, I dunno, it's disarming in a sort of way. It suddenly felt a bit precious not to do it. Normally I've just spent years putting out stuff and not bothering about it again, but for some reason I can't be that way about this record. Because it's not just my record. Other people are making an effort to get it to as many people as possible and it would be wrong to be aloof."

Costello's lyric is a wintry, disconsolate view over dockyards in the darkening atmosphere of war. Langer's music fashions a subtle minor lament for the gentle syncopations of acoustic instruments. Wyatt's singing is as lonely and plaintive as the core of the Song itself. No surprise that the lyricist was overcome on hearing the vocal.

"I had no expectations of it at all," he confesses. "All I thought about was singing it in tune! All my worrying went into singing it as well as possible."

AND NOW Robert finds himself a pop star again, nine years after an unlikely rendition of 'I'm A Believer' crept into a depressed top 30 and a group of musicians in wheelchairs appeared on Top Of The Pops.

In his Twickenham home, pleasantly cluttered with books and records, bright and airy, he sits on a hard couch, a ragged old beret and a straggly beard framing his face. Sometimes he clasps one of his ruined legs between powerful drummer's arms and swings it from side to side. He is a bit too mild and careless to be 'interviewed'.

Does he deliberately shy away from attention?

"I seem to, on the whole," he admits. "I don't mind recording and doing songs I like. But I can't speculate on things like follow-ups. I doubt it. I'm probably too old to try new tricks."

Yet it seems strange that the creator of the celebrated landscapes of Rock Bottom and Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard should have settled for the small fruits of a few singles for Rough Trade in recent years.

"Well, most of my real interests are, um...I don't think rock is a real vehicle for self-expression for me. I lead a very busy life and I earn as much money as I have to to eat. It's not that I'm not interested in making music, but it's the enforced narcissism of the industry, especially for a singer, which I find very claustrophobic. I prefer being an anonymous watcher. Part of the mob, watching from the terraces.

"I'm a singer, basically, and I'm not really working in pop music as such even if I nudge the charts occasionally. I don't know what the category is."

Has he not retreated from a jazz base?

"Not really. If you look at the musicians I choose to record with and the kind of material there is a greater affection for the mainstream of jazz history than I used to have ten years ago. I don't feel the need to try and transcend the idiom which the avant garde presumably feels its doing. I don't really keep up with where jazz is going.

"I'm more interested in looking at the essences of what it is I like about it – peeling away the novelty and looking for a permanent core of knowledge. It's fairly new core in musical terms. Nagging away at Sonny Rollins and Archie Shepp...Shepp especially, because he's rejected the search for novelty and is looking at how the masters did it. Ten years ago I wouldn't have understood why he was doing that.

"And all that's craftsmanship way beyond anything I'm capable of. I can only watch that and be inspired by it."

Robert's jazz acumen is impeccable. I reluctantly have to steer away from a detailed discussion of Shepp, Rollins and Kirk. Could he not be an organiser of sound?

"To a certain extent I have been. 'Team Spirit' from Ruth was an attempt to acknowledge all of that. But I'm not all that good. I tend to get in a bit of a flap."

Why the erratic series of singles for Rough Trade – why not another LP?

"Because I didn't have enough ideas for another LP. I chose those songs with a consistent political attitude, but even then that was down to the context. One thing I do like about the pop format is it comes in short chunks. It's very expensive making an LP and you have to have a 40-minute lump of ideas."

You could always have people doing five minutes tenor solos...

"Oh yes! I know all about that!" Robert laughs at a legacy of long Soft Machine records.

Is he satisfied with singing per se?

"Um, I get a bit fed up with the sound of my own voice," he says, a trifle downcast.

|

|

"I wouldn't mind doing some duets with Annette Peacock or something. The voice is a wonderful instrument, but I tend to get fed up...you start to realise the limitations. I wouldn't mind listening to my records in with a bunch of other stuff; but listening to ten of my songs in a row, with my voice on them – a bit much. I tend to prefer hearing instrumental music anyway.

"On the whole I don't hear words first in a song. I certainly don't judge by words. I think you listen to singing as such. I don't know – I develop theories about the relationship between songwriting and music and then I hear something like Randy Newman's 'Let's Drop The Big One' where everything matches everything else and I can't analyse why it's so good. You seem to be able to hear the words and enjoy the music all at once there."

How about wordless singing?

"I think that's even harder. You know it's a voice and you think, well, what's he really singing? What's he trying to say? Has he got a disease or something? (Laughter) We know what voices are for. They're for words. Or proto-words, like mmm!

"That would explain your point about instrumental music saying more. It formalises noisemaking and removes it from expectations. But I just don't know how music works."

Wyatt prods and noses at theories, always seems ready to give up with "I don't know" – and then returns to the point. I wonder, with this prodigious interest in cause and effect, in the mystery of music, if he had to overcome a personal snobbery over 'pop'?

"I've always had that. Most musicians from my background see songs as a launching pad – like, what's the chords on this? But I like the whole package of a good song.

"I suppose my two big influences are Mose Allison and Ray Charles cos I thought, well, you can't get better music than that. I don't think it's a question of how much you can put in to an idiom. The quality is due to selectiveness, control of your resources. Look at Monk – he played more simply than Mose Allison ever has.

"That's what's nice about working with Elvis. He's very interested in songs. Working with him I don't have to feel like a closet vocalist!"

WYATT'S WORLD is large. Some of the books piled near his stereo bracket a wide interest – Battlefont Namibia, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, The First Indian War Of Independence.

His recent recordings display an understated discontent best felt in the despairing 'Arauco', a Chilean folk tune that numbers the wages of colonialism with melancholy concern. They are records that sound steeped in private sorrows. But they are so understated. Is he envious of the sheer clout a record like 'The Message' carries, a blunt strength his own music seems afraid of?

"That's interesting...I don't know how to think about that one. The best person I've found writing about the difference between self-alienation and rejection is Julie Burchill. I wonder what she would say?"

Robert worries over it. I try and dispel his frown. Would he rather do something that bludgeoned its way past his normally spare settings?

"I used to bash about a lot. I beat shit out of the drum kit. I learnt to sing by bellowing over feedback and fuzzboxes. But I tend to work in a very piecemeal way. I don't have an overview. On the whole I'm not as much in control as the kind of questions you're asking suggest. I tend to do what I can. That's all, really."

Is he ever concerned that such an inward-looking attitude might be only selfish?

"Yes, I suppose it could be," he says. "I think people expect more of me than I expect of myself. I can't tell you how relieved I am to come out of a studio having done three minutes of singing that's in tune, with the piano roughly right, where the bass player turned up and the engineer didn't erase it.

"Really, I'm very mundane about what I do. Most of my really ambitious ideas go into my private life and not into my work. I suppose that's selfish, but I don't have the rock thing of living and feeling in public. I can't speak for a generation.

I only know about six people who agree with me on anything, and that's not much of a generation!

"I'm not being funny, because I don't know what I would have done if it hadn't been for this. I'm grateful that I can make a living at it. I don't believe in it, though. Obviously songs are about things that interest you, but it doesn't mean you're doing anything, necessarily."

Does he find the pop marketplace distasteful?

"I think people pick on it unfairly. From what I've seen of the art gallery or book publishing circuits the pop industry is a paragon of virtue! I don't see why it's singled out as a cultural red light district. But I wouldn't jump into it at the deep end because I've found another way of operating.

"Someone like Elvis really loves it as music. He puts an investment of attention into it the way I do into jazz and I suppose that's more healthy because it's the area he's actually working in."

Will he work with Costello on any further projects?

"I've no idea. It hasn't been suggested but, um...I myself don't make any plans. I just respond to what comes up. And I'm not really here. I'm living in Spain."

|

OSTENSIBLY, Robert and his wife Alfie live in Spain because "the light's better" for her painting. But he seems to feel few ties to his first home. How does England seem on his return?

"One of the great pleasures of the last six months has been having to think about that less and less. In our town in Spain there's just been a provincial election and as the results were coming through it was like a big party. All the little parties getting one and two, the Commies getting a few – and the Socialists sweeping the board.

"The area we're in is called the Red Belt, near Barcelona, and it's the strongest Communist area because there are a lot of Andalucian workers, for one thing; and right now the atmosphere there is so enjoyable, and what we've been able to join in in the way of culture and politics has been so refreshing, that it's sort of cruel to ask me to speak about England. There's a few people here still holding on to the bucking bronco but...

"I went into this Commie bar – the Commies have bars in Spain instead of handing out leaflets, more like community centres – and this old geezer came up and said, I fought alongside some English in the Civil War and they were brave fighters. Usually the people struggle to say something nice when they hear where you're from. Another geezer came up and said, the English had the first strong trade union movement in the world – what the fuck happened?"

Does he harbour any affection for England?

"I very much object to the way that there's no freedom of choice about whether you're English or not."

His voice takes on a much harder edge.

"If there was an element of choice about it then there could be an element of pride. But I don't see how you can be proud of something you're dumped with. I feel more at home with people who behave nicely, frankly. I'm homesick right now. Ten or 15 years ago there were things I might have enjoyed, but I can't feel that now. People saying Britishness is this or that has completely spoiled any kind of pride you may have had. If Britishness consists of going round the world sneering at foreigners then I don't want to know."

For the only time in our conversation, Wyatt appears angry. If his response to the legacies of colonialism is lowkey, it's still a deeply felt reaction.

"I think the dotted lines kill democracy. All the ruling people have to do is gerrymander situations. You can isolate situations like Northern Ireland, a typical colonialist trick, which makes it look like a democratic right for one side to rule another. Democracy has always been a lie, even the founding Greek democracy – an oasis of free speech in an ocean of coerced misery. I acknowledge that that's how it is and I'll even go further and say a lot of beautiful things come out of it – but be proud of it? I would like to think there's some other way of doing things."

WYATT MAKES me a cup of tea. We have Sonny Rollins on the deck – 'Blue Seven', his masterpiece of spontaneous symmetry and heat. Robert cuddles his old dog Florence. In his worn clothes and beret he resembles a salty old painter himself – Gauguin, perhaps. Sometimes he scats gently along with the massive sweep of the tenorman's voice.

Are you an optimist, Robert?

"What me? How dare you! No, but I think it's arrogant to project pessimism onto the entire universe. I can see a lot of people who are very happy.

"When I look at what gives me greatest pleasure and inspiration it seems to be the most fragile things or even the most hated or least looked-after things; and what gives me least inspiration and frightens me most are things which look very safe and nurtured.

"I suppose I envy those people for whom it's the other way around."

Richard Cook

|