| |

|

|

Pot-Head revisited - Mojo - N°43 - June 1997 Pot-Head revisited - Mojo - N°43 - June 1997

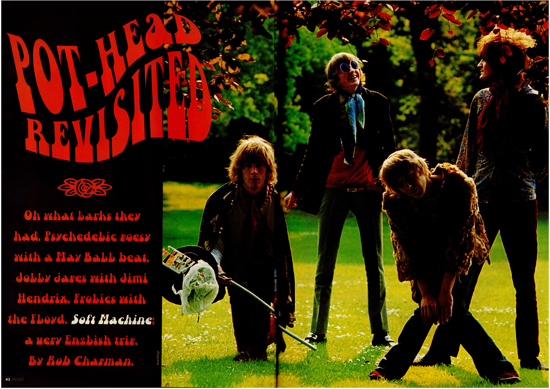

SOFT MACHINE : POT-HEAD REVISITED

Buried beneath Allen’s more publicised associations with cosmic tomfoolery and pot-headed pixies is a richer legacy. The softly spoken, eccentrically attired, gangly old hipster who sits telling me tales in his Glastonbury pad is in fact one of the great lost links between the beats and the hippies. And the band he co-founded, the Soft Machine, named after a Burroughs novel, was the underground before there was an underground.

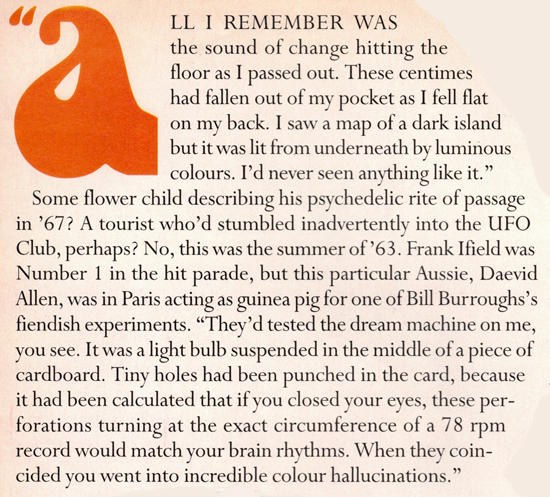

IN THE EARLY '60S, A TIME WHEN Britpop still meant Bert Weedon, Allen was holed up in the Beat Hotel, a six-storey block on the Left Bank run by the redoubtable Madame Rachou, a former employee of French intelligence, now adept at diplomatically keeping the gendarmes at bay while her clientele of exiled poets, painters, and dope dealers did their stuff. The residents included Kerouac, Gysin, Orlovsky, and Ginsberg. "A scene in every room," as Allen puts it. His first collaboration with Burroughs came in 1962 when he provided the music for a dramatisation of The Ticket That Exploded. "I was the friendly straight with those guys," he grins. "Acid used to arrive direct from the Sandoz factory in those days. You took about 18 of these little tablets. There was another one called Romilar that we took in Ibiza, which had some unknown psychedelic agent in it, and put you in the weirdest states. The locals used to call us the Romilar army."

But it wasn't all kaleidoscopic colours and dream machines. Slow dissolve to teenage stowaway on the first ship out of Melbourne harbour... Allen had left his homeland in 1960 vowing never to return. "They were still killing aborigines like kangaroos," he winces. "Those red-neck dudes from the deep north could hardly tell the difference. It was a horrific atmosphere and it's still not much spoken about. I arrive in Paris and next thing I'm sitting at the end of the piano with Bud Powell playing." Allen namechecks the jazz idols he saw in Paris: Mingus, Monk, Dolphy, Rollins. Then he hitched to England and ended up lodging at Wellington House in Canterbury. This haven of creativity was owned by broadcaster Honor Wyatt and her second husband, psychologist George Ellidge. Bohemians of the old school, they had connections with poet Robert Graves and his artistic colony in Deya, Majorca. Allen immediately bonded with their precociously talented 15-year-old son Robert. "We had the same record collection, so instantaneously we were speaking the same language," says Allen of the future Softs drummer. "He was a prodigy then, with his painting, piano playing and everything. Robert was the same intellectual age as me – which doesn't say much for me, of course – but he was in a very advanced headspace for his years."

While others dreamed of skiffle, Wyatt and his schoolchums Hugh and Brian Hopper and Mike Ratledge lived in full experimental mode. Hugh Hopper tentatively learning Charlie Haden bass lines off Ornette Coleman records, recalls a Wyatt household full of eclectic noise, ranging from Bartok to bebop, Stravinsky to Varese. "Let's just say that there was no way that Robert was going to be a bank clerk," he adds. Hugh, Brian and Mike spent the early 1960s making rudimentary tape loops and surfing the ether for obscure jazz on American Forces Network and the BBC Third Programme (since renamed Radio 3), "which carried a much more avant garde output than it does today," he remarks pointedly. "But jazz was made much more accessible by the arrival of Daevid Allen, who turned up with about 500 significant records – Monk, Mingus, Miles, Cecil Taylor, etc – which then circulated to everyone's house."

|

| |

|

|

Already no cultural slouches themselves, all of his future co-collaborators cite Allen as the galvanising force. Tape loops? This man had made tape loops with the loop guru himself, Terry Riley. "They were all 16/17," Allen reflects. "I was already the seasoned traveller, their big brother beatnik, so they saw me as a role model. Of course," he adds ruefully, "that worked against me later on. You always have to kill your role models."

Nights of atonal excess round at Wellington House and at the Hoppers' equally tolerant parents eventually blossomed into a distinctive local sound. A whole mythology has subsequently sprung up around the fact that future Soft Machine and Caravan members once shared the same postal district. "An accident of geography," Mike Ratledge pooh-poohs. "I get these German journalists asking me about the 'Canterbury music school'," says Hugh Hopper, "and with hindsight I'm sure it sounds like a great place. In fact it was a small, quite conservative market town where nothing happened. There wasn't even a university until the late '60s."

|

|

What their social milieu did allow was for the future Softs to pursue their own unique musical agenda with impunity. Isolated without being isolationist, indulgent without being insular, eclecticism was the natural order of things. It's like that Tom Wolfe remark," Ratledge says. "In seeking a personal style you plagiarise so widely from everybody that you end up with an individual style." I then get a very informative treatise on modality and process, thoroughly befitting a man who spent the Merseybeat years reading music at Oxford.

During this period, Allen, Hugh Hopper, Wyatt and Ratledge had a go at being a jazz group. They secured a residency at Pete and Dud's Establishment Club in Soho but, being slightly to the left of Oscar Peterson, they got rumbled as imposters by the supper club clientele and were slung out after four nights. They also played an ICA gig with Burroughs and Gysin, and a jazz and poetry night at the Marquee, the largely unflattering results of which, complete with Allen's delightfully self-deprecating sleevenotes, are available on a Voiceprint CD Live 1963.

Figuring that, despite his hep credentials, he wasn't going to be the next Charlie Christian or Wes Montgomery, Allen decided to become a full-time poet and headed for Robert Graves's place in Deya. He fondly recalls nights spent busking and reciting under the stars and free accommodation courtesy of Graves. It was on one of these frequent sojourns in the islands that some unlikely pop dreams began to formulate. "Kevin Ayers had some Beatles records and 'Still I'm Sad' by The Yardbirds. We did an acid trip and I thought, Bugger it, maybe I can make a living out of what I was doing before and call it pop. But first I had to adapt my guitar playing to the language of rock'n'roll."

|

|

One slight inconvenience – Allen hated rock'n'roll. To this day he wears a T-shirt on-stage with a picture of Elvis captioned "Dead Redneck". "Buddy Holly, Rock Around The Clock, all that stuff– I loathed it," he says matter of factly. Ratledge shared this sentiment. "We began to get interested in it as a cultural excitement rather than a musical one," he notes. "Forming a band was a licence to do whatever you wanted to do and call it something saleable – pop music. Kevin was the only one with a real perspective on pop music when we started."

Brought up in the Far East, the 17-year-old Ayers had moved to Canterbury in 1961. "I'd been sent from London on a drugs bust. A policeman put his hand in my pocket and pulled out a lump of hash which I could never have afforded and said, ‘’Ello ‘ello, what's this then?'. I was sent to the Ashford Remand Centre for two weeks. When the case came to court they threw it out for lack of evidence, and the magistrate said I should leave London because it was obviously a bad influence." So how did the teenage pot fiend fall in with the Canterbury avant garde? "I was a musical ignoramus, still am actually. All I'd ever heard was The Sound Of Music and Chinese pop in Malaya.

"I was drawn to Daevid and Robert and Mike Ratledge and the Hoppers because they had wider interests than anyone else around. Daevid was a complete shock to the system. He had what were for that time outrageous alternative views. He was one of the originals. At that time, though, he was more into poetry readings than songs, and I hated poetry readings."

Already adept at drinking wine and having a good time, Ayers's first serious musical collaboration with the Canterbury set was playing bass and guitar with the semi-legendary Wilde Flowers. "The name had nothing to do with flower power," Robert Wyatt told Jonathon Green for his book Days In The Life: Voices From The English Underground 1961-1971; "We lived in the country and Hugh copper had a book called Wild Flowers, and I think he thought it up." As usual there was no grand design. Future Caravan and Softs members came and went on a whim. Ayers, Wyatt and Hugh Hopper would go off and join Allen in Paris or Majorca or Morocco at the drop of a busker's hat. Ratledge stayed put in Oxford, getting his BA. Brian Hopper's compilation of Wilde Flowers rehearsals and demos, released in 1994, reveal an eclectic blend of soul, jazz, and avant garde pop, the sound of several bands in search of an identity. But early Softs motifs were evident even then: the Hopper brothers' quirky lyrics and angular arrangements, Ayers's own uncluttered songwriting skills, Wyatt's idiosyncratically soulful vocals.

|

"When I listen to those Wilde Flowers tracks now I can hear the Zombies influence," Hopper recalls. "And the English Birds too, with Ron Wood: three raucous guitars, lots of shifting chords. One of the great forgotten bands of all time." From Daevid Allen's detached viewpoint, though, it was all a bit too proper. "The Wilde Flowers suffered from the fraternal approval syndrome – it was de rigueur for any band at that time, in order to be taken seriously, to be able to play 'Papa's Got A Brand New Bag' with the right guitar sound and the right feel. But they could never get it right," he laughs. |

|

|

By the summer of '66 Allen's own plans for a beat combo, honed in the Romilar haze of the Balearics, were turning into something tangible. Three days of acid-fuelled mayhem with a night club owner from Tulsa called Wes Brunson led to Brunson pledging a considerable portion of his worldy goods to Ayers and Allen in return for them spreading the Aquarian love vibe. "Sure," they said. "We'll need musical instruments, amplifiers and somewhere to rehearse." The result was a four-piece called Mr Head, consisting of Ayers, Allen, Wyatt, and guitarist Larry Nolan. The most appropriately named group since The Small Faces entered beat competitions organised by Melody Maker and the pirate Radio London, and got the music biz agents buzzing. Mr Head toyed with the idea of changing their name to Nova Express, before settling for a slightly better known Burroughs novel. Nolan disappeared, Ratledge came down from Oxford, and Soft Machine was born.

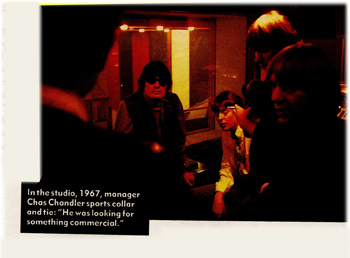

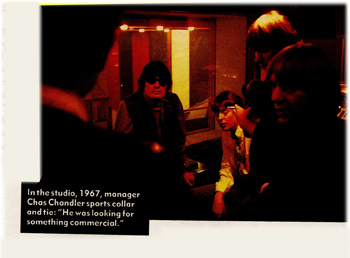

"THE NAME SOFT MACHINE CAME through Mike. He had books like V, that kind of thing. I knew the name was taken from Burroughs but I don't think it intrigued me enough to get a copy," Wyatt recalled. "Wilde Flowers more or less became Soft Machine. We trickled up to London and then regrouped, one by one. When we came up to London there were two connections: Daevid Allen had the connection with people like Hoppy [John Hopkins, underground impresario and co-founder of the magazine IT and UFO Club]. The other connection was Kevin Ayers, who played bass guitar and wrote songs. He was the only other bloke in Kent with long hair. Kevin Ayers knew The Animals' office, where Hilton Valentine and Chas Chandler were already starting to manage, and they signed us up on the basis of Kevin's songs. They were looking for something commercial. Chas was always looking for Slade, and eventually he found them; meanwhile he had to put up with people like us and Jimi Hendrix. Kevin actually got us a deal and turned us into a group that had a manager and so on. He liked bossa nova and calypso. Ray Davies and The Kinks, who started using stuff like that quite early on, were a big influence on him."

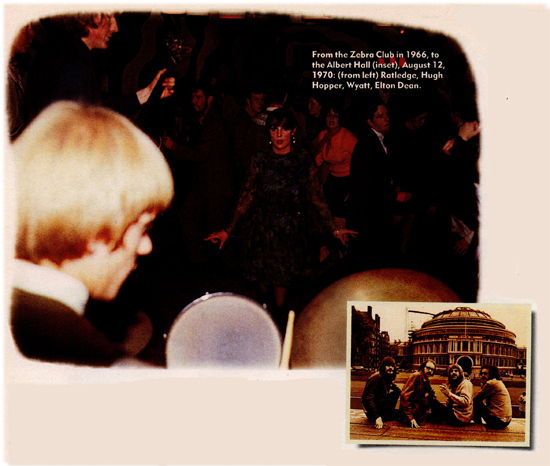

Signed to Chas Chandler's management company, the Softs spent the latter half of 1966 demoing material. Along with Pink Floyd they played seminal London Underground gigs at Notting Hill Free School and the IT launch at the Roundhouse. Like the Floyd, the Softs live favoured free-form innovation, Unlike the Floyd, they lacked a quirky little song about a transvestite to propel them into the pop charts.

|

|

"In the first Soft Machine single ['Love Makes Sweet Music'] you could hear all the peer pressures of the time," Allen says of a debut that could have passed itself off as Simon Dupree And The Big Sound if it hadn't been for Wyatt's imploring high register voice. Apart from a brief visit to the payola-ridden charts of the pirates, the single did nothing.

"I wrote it in a squalid little hotel in Hamburg," remembers Ayers. It was after we'd been fired from the Star Club – I think we lasted a day. I liked and still do like really good pop songs, and I thought I'd hit on that with 'Love Makes Sweet Music'. Had we had a good producer, and brought in a backing band, and got somebody else to sing it too... (he dissolves into laughter) it might have been a hit.

"The Pink Floyd were our rivals at that time," he admits, "and when 'Arnold Layne' came out I thought, Fuck, that's so good, and although I was quite partisan and competitive with our record, I thought there was a lot more fairy dust on theirs. There was a mania with their early stuff, and we were never manic apart from brief bursts when we played live. I think we were all too logical and clever. We could never be spontaneous enough and abandon ourselves."'

"Everyone in the media was so surprised at how intelligent we were," says Allen. "There was this interview with a BBC guy who was astonished that Mike would come down from Oxford to play in a 'pop group'."

"It was like a game at first," admits Ratledge. "It was something tangential to my life. It certainly wasn't a consuming passion." So what did he make of the underground cognoscenti? "It all seemed incredibly normal. I certainly didn't feel any disruption or change. I felt I'd been around people like that for most of my teens."

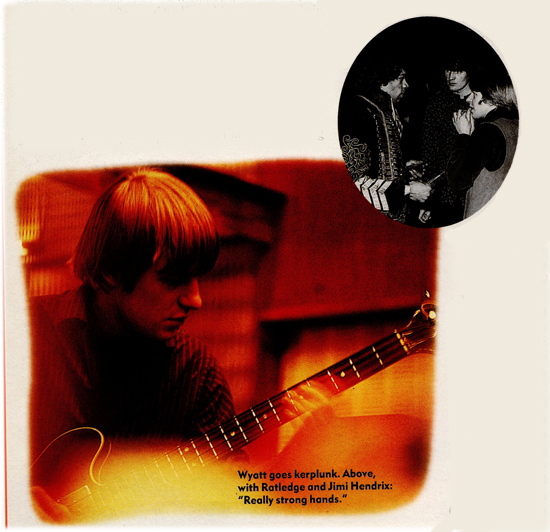

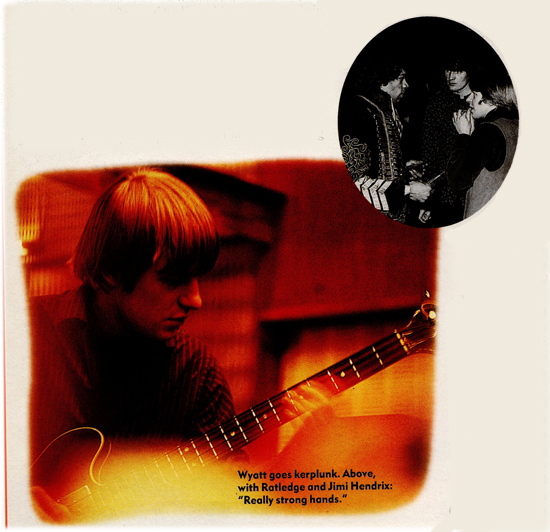

The Softs were soon introduced to another of Chandler's management proteges, Jimi Hendrix. "Kevin came back from Mike Jeffrey's office in Wardour Street," remembers Daevid Allen, "and said, 'Hey, come and catch this amazing guitar player. He's better than Jeff Beck.' Now Jeff Beck was my favourite guitarist, the most unpredictable, the most exciting, and when it really happened he could fly, but at least half the time he kicked up. When we got there Hendrix was playing with no amp yet the room was full of music. Really strong hands." ("Actually," Allen adds with a twinkle. "Jeff Beck was still more exciting than Hendrix precisely because Hendrix didn't fuck up.")

Wyatt: "Hendrix was tremendously important (or lots of people. For me too, if for nothing else than that what he let Mitch Mitchell do on drums gave me space for what I wanted to do on drums. We were using a lot of jazz ideas on drum kits that there hadn't been room for in the constricted time-keeping stuff I'd been doing before. This was the opposite of what Nick Mason was doing with the Floyd: he was kind of a ticking clock there, which is just what they needed. For electronic rock his approach was more suitable – uncluttered. People like me and Mitch were probably too busy, but at the time it seemed exciting."

|

By the spring of '67 the Soft Machine had a mid-week residency at the Speakeasy. Allen recounts fond memories of unlimited drinking on Giorgio Gomelsky's expense account and Hendrix dropping by regularly to jam the night away. "I heard Purple Haze for the first time down there," he marvels, "and it sounded like classical music to me but I couldn't see it being in the charts. I mean, how would the charts accommodate something like this?"

While the Top 10 proved itself capable of accommodating the "wild man of rock" (© Daily Mirror 1967), the UK took less of a shine to the Softs. Like Pink Floyd, they found that when they ventured outside London or the university circuit their ambience was not exactly in accord with the provincial Zeitgeist. Particularly irksome was the Kevin Ayers-penned 'We Did It Again' with its two-note bass figure nestling somewhere between The Kinks' 'You Really Got Me' and Coltrane's 'A Love Supreme'. "I had got into Sufism," Ayers explains, "and I liked the whirling dervish thing, the repetition. I always wanted to do it as a pure drone but the band always got bored with that, and kept adding things. We tried doing it like that at Chelmsford and people threw things. In fact people threw thing all the time when we did that number."

"It only happened in England," confirms Ratledge. "If you appeared with, say, the equivalent of Status Quo in England you would get booed off the stage, whereas in America, even in tiny little clubs in Indiana or wherever, they would listen to both of you. In England the expectation was that you would be a pop band and perform chart material."

"We were pelted with stuff by Move fans at the Cambridge Corn Exchange," remembers Allen. "There was certainly an uneasy truce a lot of the time."

Always impeccably well connected whether jamming at Robert Graves's place or getting mad Okies to buy them equipment, Soft Machine now fell in with the Riviera jet set. In the summer of 1967 they played a series of happenings in the South of France culminating in a gig in St Tropez's town square organised by Eddie Barclay of Barclay Records and attended by the cream of Parisian glitterati – Bardot, Delon, Godard, etc. Soft Machine's entire set consisted of an hour-ion performance of 'We Did It Again'. "It was the moment that elevated Soft Machine to the heights in the Parisians' view and put us next to The Beatles and Rolling Stones for the next couple of years," maintains Allen. For Ayers the St Tropez gig was an unrepeatable moment of musical sartori. "That was the only time 'We Did It Again' really worked," he contends. "Your best ideas happen when you're naïve. There was something magical about that early band and I would challenge Robert or Mike to disagree with that. Later on you become more sophisticated and competent but the content is rarely better." The euphoria of the St Tropez gig was short-lived. On returning to England, Allen was refused re-entry at Dover. The official reason was an expired visa, but Customs knew an undesirable Allen when they saw one. The Aussie pothead was exiled back to France. Suspicions still linger in Allen's mind as to whether he fell or was pushed out of the band. Always more assured as a catalyst than as a musician (his playing on the early Softs demos that have surfaced on record is a little unfocused, to put it charitably), he was in those days a tad self-conscious about his technical limitations. Allen recalls in his book Gong Dreaming that after a particularly fraught gig Wyatt once told him that he was ashamed to be on-stage with him.

|

|

"When somebody tells you something that you already feel, it doubles the effect," reflects Allen now, and although he claims that "being thrown out of the country was exhilarating, liberating, the best thing that could have happened to me," and talks excitedly of being in Paris during May 1968, he leaves you in no doubt that he feels the Customs incident was convenient for the rest of the band.

Ratledge sees things differently. "I was quite shocked to hear that Daevid had indicated that we had kicked him out of the band, which is not my recollection at all. He was deported and was therefore no longer available to us. I don't remember any feeling of 'Daevid must go' at the time." Saying goodbye to their big brother beatnik marked the end of Soft Machine phase one. "I only really started taking it seriously when Daevid left and we were down to a trio," Ratledge admits. "It was then that I started writing for the band."

Still languishing behind Pink Floyd in terms of UK appeal, Soft Machine found audiences more receptive in Europe and America. Live, the three-piece was a tour de force. Wyatt's vocals, all Eastern modality and hop approximations, merged with Ayers's Sufi drone over layers of fuzz from Ratledge's trusty organ. "We couldn't afford a Hammond, which was the authentic article," Ratledge explains, "so I was playing this weedy Lowrey and I wanted to approximate the power that Hendrix had. I got sick of guitarists having all the balls."

It was during a break in their first major US tour in April 1968, a full year after Piper At The Gates Of Dawn, that the three-piece Softs finally got to record their first album. Producer Tom Wilson had worked with Dylan and on the Velvet Underground’s debut. "Which is presumably why he was hired," says Ayers. Despite Wilson's pedigree, and some great material, the resulting mix was clinical and lacking in dynamics. "We started out with some very good ideas," contends Ayers, "but that album was amateurish, sloppy, badly produced – a nightmare, now I look back on it. All he did was phone his girlfriends. I think he thought we were a bunch of little white shits playing this unfunky cerebral caterwauling."

The album, with its distinctive 'pin-wheel' cover pre-dating Led Zeppelin III by two years, finally came out in November 1968 on Probe. Shamefully, to this day it has never received a full UK release. Sleevenotes of colossal ineptitude written in period "hey cats, dig their scene"-style were provided by Arnold Shaw, better known for his showbiz hagiographies. Certain tracks on Soft Machine – Brian Hopper's 'Hope For Happiness', Wyatt's 'Save Yourself' – were adaptations of material from the Wellington House days. The "head is a nightclub" line on Ayers's seminal 'Why Are We Sleeping' was taken from a Daevid Allen jazz poem. Very little from those early days was ever wasted. Perhaps the most beautiful moment on the Softs' inauspicious debut was Ayers's instrumental 'Joy Of A Toy' (the title taken from a Ornette Coleman track), later reactivated for Ayers's solo debut. "I used a Gibson bass with nylon strings on that," he remembers. "Good for playing lead lines but not so good for a traditional bass sound. It sounds so elastic-bandy and plunky on that first album."

Soft Machine had been recorded in one four-day session while on tour with The Jimi Hendrix Experience. In contrast Hendrix recorded his indulgent masterpiece Electric Ladyland over a leisurely six-month period during the same marathon stint. "On the first part of that tour with Hendrix there were moments of sheer magic," says Ayers. "I found Hendrix a very gentle, very sad guy. He was being ripped off emotionally, financially, and he had to strap on an enormous amount of chemical armour before he could become Jimi Hendrix on-stage."

The tour, which took up most of 1968, almost split the Softs for good. "I got heavily into macrobiotics on the second part of the tour," remembers Ayers. "I stopped drinking, stopped smoking, which was totally incompatible with the routine of touring. My energy level went right down and I was falling about all over the place. You can't do a two-hour gig on a green apple, a glass of water and a bowl of rice."

Hugh Hopper was a roadie with the band at this point. "When I look back now I think, Great, I was on tour with Hendrix," he laughs, "but I never not to see much of the music, and even when I did I couldn't appreciate it because I was so knackered. It wasn't 16 articulated lorries like you have now. It was me and Hendrix's roadie with one van praying that we would get to the venue on time. Hendrix was becoming really big during that period, so as soon as there was a gap in the schedule it got filled, and we ended up touring for months without a break. It did Hendrix's roadie's head in completely. He abandoned the van in the streets of New York at the end of it."

It did Ayers's head in too; he fled to Ibiza to regain equilibrium. "Mike and Robert were far more musically literate than I was, and I think my simplicity bored them," he says of his departure. "I met Terry Riley and Gil Evans in New York and I liked all those jazz pieces Daevid and Robert introduced me to, but it was all way beyond my musical comprehension, and I didn't have the interest in playing things in 19/7 just for the sake of it. I never really liked 'fusion music' or whatever it was called, even the slick American stuff. I much preferred the jazz as it was to start with, and rock as it was to start with. Fusion all seemed more fun for the players than the listener. People with virtuoso techniques blasting at each other to see how difficult they could be." He dissolves again into mirthful disdain. "So I took my simplicity elsewhere, and lost this family. Being in a pure spiritual state at that time, clean of body and mind, I wasn't terribly worried. It only hit me later on that I was no longer close to these people."

Ayers gave his bass to Mitch Mitchell ("I still do that, actually: 'Take my house, my car, my wife.' I burn bridges."), and trainspotters might like to note the similarities in plunkiness between Ayers's aforementioned 'Joy Of A Toy' and Noel Redding's playing on '1983 (A Merman I Should Turn To Be) on Electric Ladyland'.

SOFT MACHINE EFFECTIVELY DISBANDED. RATLEDGE, LIKE Ayers, was burned out by the American tour. Wyatt hung out with Hendrix in LA and nurtured vague plans to pursue a solo career. Forced to record a second album as an obligation to Probe records, and with Ayers disinclined to budge from his sunny retreat, Ratledge and Wyatt brought in Hugh Hopper as a permanent replacement.

Kicking off with Wyatt's introduction to "the official orchestra of the college of pataphysics" and a scholarly rendition of the British alphabet, the resulting contract-fulfiller turned into a Canterbury classic. Full of self-mythologising little touches like Ratledge and Wyatt's warm referential nod to Kevin's macrobiotics, 'As Long As He Lies Perfectly Still', Soft Machine Volume 2 takes us back to a time when Pere Ubu was still an Alfred Jarry character and not a group from Cleveland. Daevid Allen described Jarry's notion of pataphysics to me as "creating a spiritual manifesto in an absurd form, casting a serious topic into an absurdist structure," something he turned into a fine art with Gong. Ayers also applied the principle to his post-Soft Machine work, probably to the detriment of his career. When asked to elaborate on the mechanics of pataphysics, Ratledge talks vaguely of "the science of the impossible" and "perverting the premises of scientific certainties." And how did you apply that to music? "We didn't. Not in the least. Are you kidding?" He rocks with suitably absurdist laughter. "Soft Machine 2 was people celebrating enthusiasms for things outside the music, be it French literature or whatever. Often song titles were just adverts for things we liked: Read this, listen to that." Indeed. Like many people my age, I first picked up Burroughs's book The Soft Machine thinking it was a biography of the band. "See, it worked," he says with evident satisfaction.

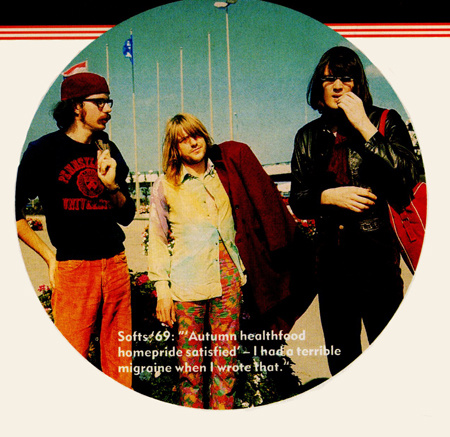

Aside from the toe-tapping tributes to Pierrot Lunaire, and Dada and Jarry it's Hugh Hopper that really comes into his own on Soft Machine Volume 2. How could this bookish-looking bloke with curly receding hair, hornrims and 'tache write such exquisitely English songs? He still looks like he would have been more suitably employed in a professorial capacity at the college of advanced pataphysics rather than playing his debut Softs gig with Hendrix at the Albert Hall. One of the most magnificent moments on Soft Machine Volume 2 is when Wyatt sings Hopper's 'Dedicated To You But You Weren't Listening'. "Don't use magnets geophysics/carry you back/autumn health-food homepride satisfied," he enunciates in tones of utter conviction. "I had a terrible migraine when I wrote that," Hopper offers a tad obliquely.

As Wyatt ruefully recalled, "One record company bloke told us, ‘I don't know whether you're our worst-selling rock group or our best-selling jazz group'."

MOST OF THE TRACKS ON SOFT MACHINE VOLUME 2 SEGUE into each other, a common enough jazz device at the time, although Robert Wyatt later justified the Softs' use of continuity as a defence mechanism against hostile audiences – it's harder to boo when there aren't any pauses. By 1970 such defensiveness was becoming increasingly unnecessary. In the summer of that year, and arguably at the height of their critical acclaim, Soft Machine were invited to perform at the Proms. No longer a bunch of cerebral hairies playing with their backs to the audience, they now had prestige. Radio 3 respectability beckoned. Again Ratledge was characteristically unfazed. "We'd played the Albert Hall twice before. It was just another gig. One was never surprised by anything during that period. I'm much less blase and more surprised by life now than I was then. The organisation though was a nightmare. The equipment was held up in Spain, there was no proper soundcheck." Even worse, the Softs were restricted to a 45-minutc set. "And because it was televised," adds Hopper, "they needed lots of light so we were all blinded on-stage. By our standards, it was a fairly duff gig."

More ominously, the Proms performance masked severe internal divisions within the band. The release of their double album Third, just prior to the Albert Hall gig, revealed a more overtly jazz-influenced direction. Feeling increasingly limited by writing for a trio, the band was now augmented by stalwarts of the burgeoning English jazz-rock scene like Elton Dean, Lyn Dobson, and Nick Evans. The album, in many ways the culmination of many of the Soft Machine's defining impulses, was largely instrumental, featuring lengthy solo and ensemble work-outs.

The exception was Wyatt's classic montage of life as seen from a New York hotel room, 'Moon In June', with which the others refused to have anything other than minimal involvement. The evident hurt this caused Wyatt was a major factor in his eventual departure from the band. Always the most extrovert member of the Softs – on-stage his long hair flailing and exuberant drumming contrasted sharply with Hopper and Ratledge sitting hunched over their instruments – Wyatt found himself increasingly cut adrift in a sea of cerebral noodling. To break out of the confines, Wyatt's extra-curricular musical activity at this time included stints with Keith Tippett's Centipede, Kevin Ayers And The Whole World and the Spontaneous Music Ensemble.

I remind Hugh Hopper of a story where a purist prog fan went backstage circa 1970 to congratulate the Softs on a great gig and to sneer that they'd had to endure Geno Washington And The Ram Jam Band a week earlier. "We'd play like that if we could," Wyatt had allegedly commented. "Oh absolutely," confirms Hopper. "I remember Robert meeting Phil Chen, the bass player with Jimmy James And The Vagabonds, and being knocked out by all these Temptations bass lines he was playing. But Robert always took stances: if everybody in the band was being freaky and avant garde, he'd have a month of championing Steeleye Span just for the effect it would have."

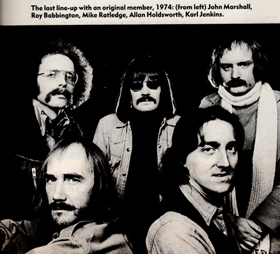

Shortly after the Proms gig Wyatt recorded his own solo album, End Of An Ear. According to the liner notes Wyatt penned for the album's 1992 CD reissue, this venture hastened his own departure from the Softs. "Perhaps – I was never told why – I was expelled soon afterwards from my original group by the very people I had invited to join it," he observed ungrammatically but, it would appear, accurately. "It was much more tricky than Kevin's departure, which was entirely amicable," Ratledge acknowledges. (Indeed, all of the Softs had subsequently reconvened to play on Ayers's first solo album.) "But after that tour with Hendrix things had polarised between Robert and everybody else. Hugh, myself and Elton were pursuing a vaguely jazz related direction. Robert was violently opposed to this, which is strange, looking back on it, because he was passionate about jazz. But he had defined ideas about what pop music was and what jazz was. I think, like Kevin, he'd made conceptual decisions that pop should remain pop and jazz should remain jazz. And although the so-called conspiracy between Hugh, myself and Elton covered a lot of actual differences between us, we had sufficient similarity to define ourselves against Robert.

"The whole situation in the USA got very complicated. Robert used to walk off the stand because he didn't like what we were playing or writing; you can't sustain a situation where your drummer is walking off the stand maybe one in four nights." "There were nights when we would make fun of him behind his back, admits Hopper. "It really had got that bad. Mike and I couldn't stand Robert and he couldn't stand us. We were very cool and calculated whereas Robert was very open and impulsive. During one evening of drunkenness at Ronnie Scott's he said to someone, ‘I wish I could find another band’. The rest of us leapt on it and said, 'Right, go on then'. Robert was definitely pushed out of what he felt was his own group. He'd been one of the instigators, after all. And he seems as bitter about that now as he ever has been."

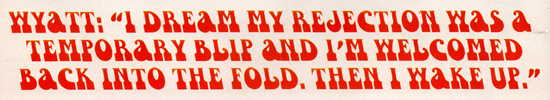

This much is brought home to me when I contact Wyatt for a contribution to this feature. Back comes a postcard with that familiar childlike scrawl and skewed diction. "I still have nightmares or rather daymares," it reads. "I dream my rejection was a temporary blip and I'm welcomed back into the fold. Then I wake up. How bad was I affected by my being deported from SM? Well breaking my back was easier to deal with. That's how bad." Further qualified enquiries to the man whose music I admire more than that of any other living Englishman get a similarly unyielding response. It would seem that even after all this time there is still too much pain.

"We handled it clumsily," concedes Ratledge with considerable understatement. What is so sad is that the Wyatt-Softs split seems to be indicative of the way the whole musical family gradually fell apart. The Canterbury forefathers have minimal, if any contact with each other these days. Some haven't seen each other for 20 years.

"Nobody in the band was trying to do the same thing at all, which is why it was quite original and why, after a couple of years, it fell part," Wyatt recalled 10 years ago. "It was a constant process of disintegration really, getting in new people to fill the gaps. Which in the '60s was rare, because most bands were quite stable. I talked to Nick Mason of Pink Floyd about that once. I said, 'How come you lot have stayed together so long?' and he said, 'We haven't finished with each other yet.' But it kept changing, we kept on tinkering with it and tinkering with it and throwing each other out of it and leaving it until eventually all the kinks were ironed out, and in the end it became a standard British jazz-rock band. I don't know what happened in the end. I stopped listening after a while – I stopped listening before I even left."

The whole sorry situation elicits a cautious summarising from Ratledge. "The very reason why the band was so good – with everyone pulling in different directions – became unsustainable. It reached a point where everyone wanted to do what they wanted to do so strongly that you couldn't have any sort of compromise. Nobody in that band was going to do anyone else's thing any more. It's the price you pay for being committed. You can sustain a band on compromise for years if there's no passion there."

EVEN THE ALLEGIANCE TO THE ENGLISH JAZZ ROCK scene was, it would now appear, something of a mismatch. "I never felt part of that English jazz scene," says Ratledge surprisingly, "and the more we included those kind of players in the band the more difference I felt between me and them, mainly because writing was very important to me and jazz at the time was very improvised and anti-writing. Hugh was much more at ease with that kind of departure than I was."

|

|

But Hopper has equal misgivings about the jazz-prog detour taken the band after the early 1970s: "I was very influenced by Uncle Meat and Hot Rats-period Zappa, but that whole jazz rock territory subsequently became very devalued. For me the best stuff was a mixture of real weirdness and good writing. Zappa was a great writer. But what you ended up with was lots of good technical players who didn't have that weirdness that could lift it." Hopper left after the Softs' sixth album strayed down the creative cul de sac of English jazz-rock. "I've enjoyed playing music much more since leaving Soft Machine," he concludes.

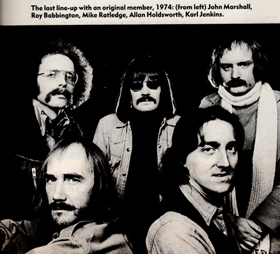

Ratledge was the last of the originals to leave. Conceding that he delayed his departure about a year too long, he left at the end of 1975, after album number eight, by which time Soft Machine had become just another finishing school for English fusionists. "It had stayed static for some time," he admits. "It had become a gig,"

For Ratledge a whole new successful career in TV ad music opened up, far removed from jazz-rock improv in tricky time signatures. "In a curious sort of way, everybody discovered their individuality by being in the band," he concludes. "We all tried to do something cohesive to work out what we had in common but everyone was acting out some idea of what they thought pop music was, and the longer it existed everybody wanted to pull in different directions. That was both the reason for its success and the reason for it falling apart."

Rob Chapman

Photos : Mark Ellidge, Pictorial Press, LFI, Hulton Getti, T. Russell/Redferns

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|