| |

|

|

The

MOJO Interview - Mojo N° 144 - November 2005 The

MOJO Interview - Mojo N° 144 - November 2005

THE MOJO INTERVIEW

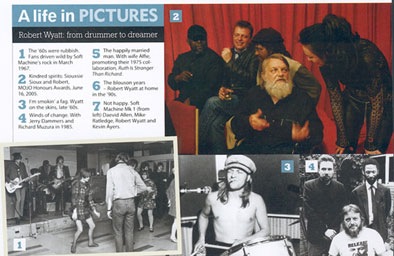

Soft

Machine made him miserable. Falling from a window

in 1973 was "a good career move". Enter

the topsy-turvy world of rock's reluctant Mr Nice Guy,

Robert Wyatt.

Interview by MARK PAYTRESS

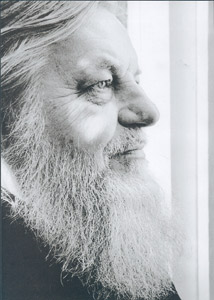

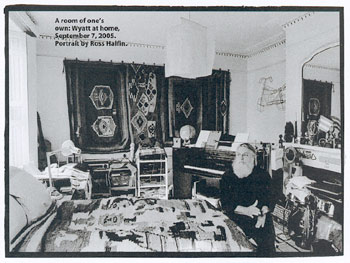

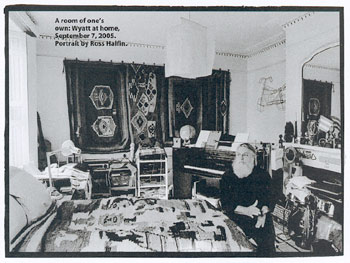

Portrait by ROSS

HALFIN

|

alternative cover

|

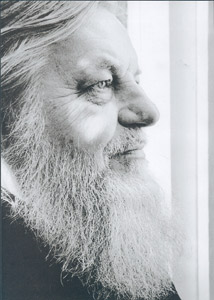

ROBERT WYATT IS MAKING HIS WAY TO THE nearest mirror.

"My wife goes mad if it looks crap," he says,

teasing unruly strands of silvery hair away from his face.

It doesn't seem to make much difference. As he poses affably

in his small front garden, oblivious to the bustle of

the Lincolnshire market town passing by his gate, this

softly-spoken god of small things still sports the unkempt

19th century Russian thinker look he's maintained for

over a decade. He's all facial hair and kind, youthful

eyes, and no 10-second makeover can alter that.

Inside, across a wooden dining table, Wyatt discusses

everything that's thrown at him with generosity and insight.

Moving effortlessly from Richard Dawkins to Don Covay,

from father of anarchism Peter Kropotkin to flamenco siren

La Niña de la Puebla over wine, fags and omelette,

Wyatt is fascinated equally by musicians and ideas. Especially

those, such as Hendrix and Miles Davis as well as innumerable

unnamed fighters

for economic and social justice, who push themselves a

bit beyond what we know.

|

|

Wyatt, too, inhabits the realm of

the unthinkable. Less than two years after the singing sticksman

had been unceremoniously dumped by The Soft Machine, on

June 1,1973 he fell from a fourth-floor window ("I'd

always been a bit reckless," he explains) during a

party, which turned his life round for a second time. Left

paralysed and wheelchair-bound, he insists he simply got

on with the job. But when he leaves the room, his wife Alfie

helpfully suggests that "the trick has been denial".

Ostensibly, MOJO is here to discuss the release of Theatre

Royal Drury Lane. This September 1974 set chronicles

his one and only solo live show, including his masterpiece,

Rock Bottom, in its entirety. Since then, he's become

a cherished institution, thanks to a string of inimitable

and idiosyncratic, keyboard-led solo records. Unafraid to

speak up for the common people, Wyatt won the respect of

punk audiences, who loudly applauded his integrity. But

most cherished of all is his voice, the most plaintive,

deeply affecting in popular music. Refreshingly unassuming,

Robert Wyatt is rock's most reluctant legend.

This latest archive release [Theatre Royal, Drury

Lane] was your coming out a year on from the accident

in 1973. Was it difficult to listen to?

No. It's the sound of freedom compared with my previous

responsibilities as a drummer. What I hear are the technical

things, the purely musical things. The content I have to

take for granted.I don't listen like a listener.I would

have loved to have taken that band on the road, though with

Fred Frith, Mike Oldfield and Nick Mason involved, that

was clearly never gonna happen. And John Peel's intro is

one of the best solos on the record. He sets up an atmosphere

that a good MC would have done opening a 19th century music

hall show - very light and easy.

Privately, it must have been a different matter. How

low did you go?

The truth is I wasn't low after the accident. I may have

had the bends coming up too fast, so I may have been a bit

deranged, but I can't call it sadness. I'd just got together

with Alfie. For the first time I had people helping me do

my own tunes. Being rejected by the burgeoning jazz-rock

community [dismissal from The Soft Machine] was far more

humiliating. That was when I was miserable, before I broke

my back, before I met Alfie, before I started a new year

zero in '74. It's actually quite a celebratory moment for

me.

So, contrary to popular opinion, Rock Bottom wasn't a

direct response to your new state?

My overall view of life, not my circumstances, is that I

am rather sad. I think life is wonderful, but my tendency

is towards great sadness about things. I don't know why.

While that may come out, it's not something I consciously

put in. I operate like an animal - I just go for what feels

right. People say humans have a fantastic ability for selective

memory, that they erase pain because a certain amount can't

be lived with. So it may be possible I was more distressed

than I remember. But when you've fallen down a hole, and

are scrambling out, you're not really sad.

|

|

|

|

One night, you're a well-known party animal. The next

you're sobering up in a hospital bed and have just been

told you've lost the use of your legs. What was your first

thought?

I thought it was interesting, odd. It was a bit like being

lifted up by helicopter off a street and dumped on a beach

in Java. You think, Where am I? Is anybody here? I don't

know the language. The world looks the same, but you're

so different in a wheelchair that you have to re-learn how

to live, the oddness of being in the same place but not

being able to participate in the same way. I must emphasise

that I was very unhappy in the late '60s, deeply uncomfortable.

It's not as if I'd lost something that was very precious

to me.

Did you tell yourself: I'm gonna beat this?

No, l'm too short term for that. I thought, Blimey, I think

I might have enough material here for another record - that'll

be good. But I only had about three or four chords I liked.

I wanted to expand the repertoire... to about six.

Where did you look for inspiration ?

Alfie taught me how to look at films in a more educated

way, and though we had a lot of music in common - Sly Stone,

Mingus - she listened to flamenco, Bulgarian folk music

and so on, which had an enormous effect on me. To discover

that the spirit of soul music is all over the world was

a revelation.

From a young age, you'd cherished outsiders through your

admiration of jazz musicians and bohemian culture. Did this

help?

I hadn't thought of it like that, but the answer is yes.

If you're feeling lonely with the world because it seems

to be made for somebody else but not for you, then to find

other people that it's not made for either, who are uncomfortable

in their own ways, you get a certain fraternal sense of

relief from that.

What did music, especially your early passion for jazz,

first mean to you. Escape? Intoxication? Removal from the

humdrum?

You've nailed it!

There's a childlike sense of wonder to your work, and

hints of Christmas carols and nursery rhymes in your melodies.

The first songs I sang were with my dad round the piano

at Christmas - Away In A Manger and Silent Night. It's folk

music, but like a lot of folklore, it survives as children's

music and stories. It's not a deliberate, 'Life is complicated,

I'm going back to my childhood' thing. It's simply that

when you're a child you experience things for the first

time, and a lot of things are astonishing. And it's that

astonishment that's the basis of the art I like. That's

what I try and release when I turn my [creative] tap on.

But you can be made to feel a bit of a fool. I had an LP

once, and the back cover was just a blank blue piece of

shiny cardboard. And I said to the person I was with at

the time, "Isn't this beautiful?" She said, "Not really,

it's just a bit of blue cardboard." That made me feel a

bit sheepish about it. I don't know if that's right or wrong.

Maybe I'm retarded.

|

|

|

Your parents both knew the writer

Robert Graves, were well travelled and seemed to provide

you with an aestheticised world view.

Yes. The only thing that doesn't ring true is that it's

always described as if there was something luxurious about

my upbringing. But my parents were fairly poor and we

lived a fairly scruffy life, as most people did after

the war. It wasn't as grand or precious as the word 'aesthetic'

makes it sound. As far as my dad was concerned, the world

revolved around wine, women and song. If that's aesthetics,

then I'm an aesthete!

I sense you had a smell under your nose when beat music

arrived in 1963.

Beat music was a bit too boy-next-door to get romantic

about. But it was encouraging to think that there was

something I could do. I'd been interested in Eric Dolphy

and Dada and Picasso, and I didn't want to work in an

idiom that closed that off.

In fact, you have a quite jaundiced view of the entire

'60s decade.

There's this surrealist map of the world where they made

some places very big, like Africa. My surrealist calendar

of the 20th century would go straight from 1959 to 1971.

People say that life was so boring in the '50s, and thank

goodness for the '60s. My life wasn't boring in the '5Os.

As a young teenager, the whole business of beats and beatniks,

and the music, these incomprehensible French films, the

berets and the wines and the strange back alleys of Soho

and Paris that went with it, was so exotic and romantic.

I didn't need the breakthrough the '60s provided for others.

You were a significant part of The Soft Machine, an adventurous

pop group doing something unprecedented. Thrilling, surely?

We were just trying to harness the various things that

came into our heads and make something of it. That's all

remember. Only recently when some labels started digging

up old concerts from the late '60s and early '70s, I'd

listen to them and think, Blimey, we weren't half going

at it. It's a relief that it's not always as embarrassing

as I thought it might be, though some of it is. There's

an awful one that should be burned, destroyed, but you

know how perverse people are, they'll go and buy it! It's

like having a tattoo on your arm that you can't get rid

of.

You were with The Soft Machine musicians in various

guises for the best part of a decade. You must have believed

in what you were doing.

It was important for me to be with musicians that might

not normally play together, rather like putting garlic

on cornflakes. The people I played with wouldn't try to

play like somebody else. I liked the idea that what they

played came out of themselves, and was not prompted by

wanting to make, say, a jazz-rock record. I remember thinking

it was better to be original and get it wrong than be

derivative and get it right. It was an adventure to the

point of recklessness.

You're very open in interviews yet always profess near

total amnesia when discussing Soft Machine. Can the collapse

of relationships in a pop group really have been of more

significance to you than the accident?

I once asked Nick Mason why the Pink Floyd keep going.

He said, 'We haven't finished with each other yet."

But we had, obviously. Well, they'd finished with me.

It's silly to talk about a group. It's not a living thing,

just a word to put on a concert bill or a record cover.

I'd rather work the way they do in cinema, where you get

a bunch of people together for a particular project. But

I'm grateful for the discipline and the training that

being in a young group gave me.

|

"Harmless

is as good as I dare aspire to. Beyond that I'm

totally self-indulgent and hedonistic."

|

Your gorgeous, side-long solo epic,

Moon In June, on [Soft Machine's] Third must have suggested

a possible way out.

The only way to play that was for me to do it virtually

myself. The dominant thing in my head was to take responsibility.

I was doing more and more things that were quite incompatible

with the band I was with, that weren't really rock band

things at all. Moon In June was the second of two things

I'd done myself. The first was taking these fragments

of tunes that Hugh Hopper had written which I stitched

together on the second Soft Machine record. The next was

my stitching my own bits and pieces into a sustained sequence

which became Moon In June.

By calling your next band Matching Mole, which roughly

translates as "Soft Machine" in French, was

that a case of not letting go?

It was me saying I was still in that band in my head.

I could have called it Soft Machine. I can now announce

to the public that in fact we were never allowed to register

the name. Anyone can call themselves Soft Machine if they

want a quick shufti to the top of the bill!

How did you cope now you were the boss?

To my dismay, just as I wasn't very good at being told

what do to, neither could I tell other people what to

do. I now think that everything was leading to me making

my own records. But the musicians I worked with were terrific.

Phil [Miller] wrote the tune for God Song. O Caroline

was basically a duet with David Sinclair. But we didn't

have any money or resources. The others took all that.

It was very hard.

The title and cover of Matching Mole's Little Red

Record clearly suggests you'd become politicised by the

early '70s.

The cover was actually chosen by someone at CBS who'd

heard the lyrics, found this poster of the imaginary liberation

of Taiwan, and put our faces on it. However, the world

drifting to the right took me by surprise. I thought the

era of moustached racist colonels in their mock Tudor

houses in Whitstable was becoming a thing of the past,

but to see whole new generations picking up on those ideologies,

that imperial nostalgia, made my skin prickle. I thought

my parents' generation sorted all this. It was quite clear.

Are we on the side of the rich, trying to stay exclusive,

engineering this endless character assassination against

less lucky people? When the guns are firing, there is

no middle ground. My tendency is always to err on the

side of the exploited.

Did the accident make you more militant?

Not directly. I've disappointed some disabled people by

not using my work as a platform to fight for our rights

of access. But if it hasn't caught your imagination, you

can't pretend it has. Yet having to yield control of the

situation you're in, a dilemma most severely disabled

people know well, I can recognise in a lot of the battles

going on in the world.

|

|

|

|

Do you need to be a good man?

I want to be harmless. That's as good as I dare aspire

to. Beyond that, I'm totally self-indulgent and hedonistic.

You're famous for your postcards, written on the back

of cereal packets, sent to friends and admirers. My sister

still has one from the early '80s where you complain about

your nice guy image and sign off as "Bolshie Bertie".

Are you uncomfortable with the Mr Nice reputation?

Sometimes I have to work at a compassionate view towards

what other people have done. I can get very impatient

and angry as an initial reaction. But ideally the goal

would be, to understand all is to forgive all. It's a

magical phrase.

But when a population votes in a government hellbent

on destroying their livelihoods, as in the case of Thatcher,

you must despair.

Well, I'm quite happy to sing a song like Shipbuilding

by Costello, who felt exactly that, a rage that had to

be exorcised in some way. That kind of rage can give you

energy. But it's different from the cool mantle of wisdom

that judges assume, which is almost inevitably bullshit.

It seems to me that a nice person wouldn't have such a

battle with all this stuff.

Earlier on, you mentioned hedonism. Is intoxication

important to you?

I do have an intense greediness for stimuli. I get bored

quickly. But I'm really scared of breaking the law. Pathetic,

isn't it? Some musicians blast themselves with stimuli

in order to blast their own rockets off to go into outer

space. I wouldn't be alive if I were on my own. Alfie's

kept me alive. My ideal state is to do absolutely nothing

in a complete stupor listening to Charlie Mingus records

very loud in a candle-lit room - with Alfie.

So your fall in 1973 saved you?

Yes, that's the way it looks to me. It was a good career

move.

|

|

Keith Moon apparently taught you how to drink heavily.

What is it with drummers?

I learnt how to get very drunk very quickly with him in

New York. Drummers are hopeless; we don't get our things

together. Maybe because it is extremely physical, it's

possible you get into a certain state, that some chemical

thing happens.

It's obvious that Alfie is your inspiration, your sounding-board,

your collaborator. And, as she says, also "your guarder".

Do you ever yearn to nip out and have a few sneaky beers?

I do. The trouble is it's hurtful for Alfie. If I'm

left to my own devices, I do seem to be amazingly irresponsible,

so I have to be grateful for someone who points these

dangers out in advance. I'm not quite sure how to function

safely in the world. I would be much better for her if

I looked after myself better.

You survived punk. Did you feel a genuine affinity

with it?

Yeah, the working methods, the attitude and the tunings.

It was a very witty movement, an autonomous one that wasn't

invented by fashion stylists. I thought they were very

moral young people. A lot of people were thinking hard

about the rise of the National Front, and the relationship

between young rastas and punks was very ahead of its time.

Some cracking records too.

In the '80s you spent quite a bit of time in Spain

and Italy. Then you moved from west London to Lincolnshire.

Is this indicative of a make-the-world-go-away philosophy?

We had a busy life abroad, recording, doing television

and attending ANC meetings. I didn't need to be part of

the rock world back here. But sometimes a certain distance

is required. If you create a comfortable distance between

yourself and the world you have to deal with, you can

keep control of your own bit of it. But if I'm asked my

ethnic group, I always say "Soho". In my heart I'm still

hanging round Ronnie Scott's foyer. I could spend the

rest of my life there, and I do in my head, just by choosing

the right records.

Over the past 20 years, you've released a record roughly

once every five years. The curse of perfectionism, perhaps?

I'd love to be a perfectionist. I always think I am until

I hear the results, then I realise I'm not.

Cuckooland, the title of your last album is such

a Wyatt word, vaguely archaic, full of echoes.

I'm really amused by words that have some sort of folk

memory, and I love half making up words, because that's

how they came to be in the first place. Cuckooland is

ambiguous. Either the world is really as mad as it looks

to me, or because that's how my brain is, it's me that's

in Cuckooland.

John Peel was a long-time friend. How did his death

affect you?

Terrible. A death in the family. I was asked at the time

to respond in the media and I couldn't. Me and Alfie,

John and Sheila, and John and Helen Walters became friends

over the years quite apart from the professional connection

that brought us together. Sheila is putting together a

CD for the anniversary of his death. I was asked yesterday

if they can have Shipbuilding for it, and as far as I'm

concerned, Sheila can have anything of mine she likes.

The world seems to be filling up with so many friendly

ghosts. As long as you have people in your head, that's

the nearest thing I understand to immortality. People

live on through the people who loved or remember them.

So death is not something you worry about.

Not at all. It is difficult for the people that are left.

The people who are dead are at peace.

|