| |

|

|

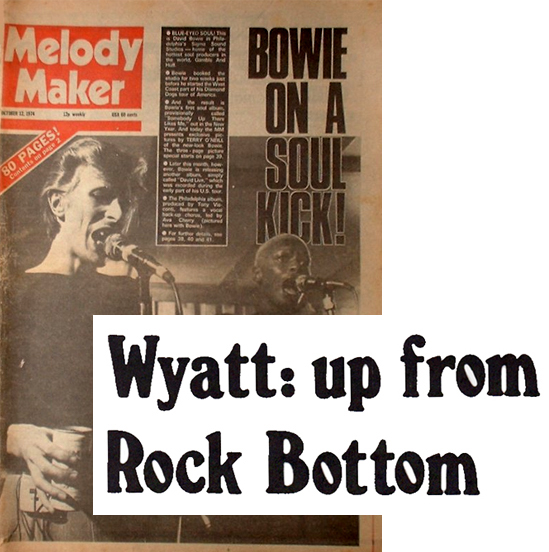

Wyatt: up from Rock Bottom - Melody Maker - October 12, 1974 Wyatt: up from Rock Bottom - Melody Maker - October 12, 1974

| |

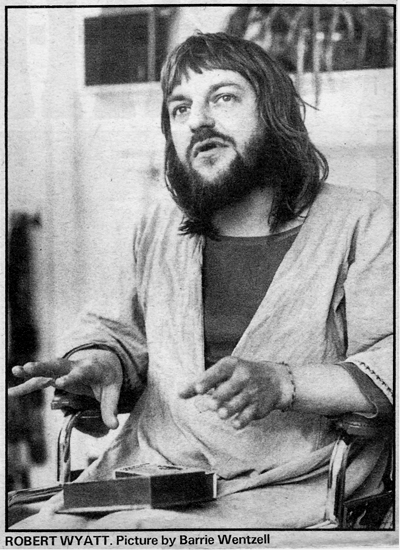

Robert Wyatt, 29, a gentleman never renowned for his dress sense, leans forward in his

chair and hoists the hem of the kaftan/nightshirt affair he's wearing up by two or three inches.

|

|

|

Involuntarily, I gasp. Glitter! Not a profusion, admittedly, but unmistakably there… Robert Wyatt is wearing rhinestoned carpet slippers, folks. Can this be?

Can yesterday's jazzer really have “gone glam”? He nods his head shrewdly.

“You can tell Gary Glitter – he might as well forget it, because by the time I'm finished, he's going to look hopelessly functional and tame.

Come Christmas time, when me beard's a bit longer, I plan to sport a string of fairy lights, from ear to ear. And I'm also considering the possibilities of a flashing neon street-sign for me wheelchair. How can Glitter compete with that?”

How indeed?

Don't you realise, I suggest to him, that the average reader is very probably a mite confused by the sudden change of direction that your career has taken lately? After all, from the heads-down seriousness of the drum chair with the Soft Machine to Top Of The Pops appearances crooning Neil Diamond tunes is hardly the most predictable of paths.

Wyatt thinks deeply for fully four minutes or so, scratching his head, face screwed up in concentration.

“Good,” he says finally, and promptly clams up again, pouring himself a fifth sherry.

“What I would like to say to your readers,” he volunteers, “is ‘Why are you reading about somebody boring like me when there's a history of the Ronnie Scott Club by Max Jones elsewhere in this very same issue?’”

(See what I mean?)

Actually, “boring” is one thing the Robert Wyatt story is not. For despite his own embarrassment about his entire recorded output prior to the Virgin Records' “Rock Bottom” album, his achievements, personally and musically are pretty extraordinary.

Think about it. While Britain, in late '67, was recovering from an overdose of imported Flower Power and every soul band in the land had suddenly become a “head” outfit (viz the changing of Zoot Money's Big Roll Band into Dantalion's Chariot), the Soft Machine, unquestionably the most articulate of all the post-UFO crowd, were elsewhere.

Building up a heavy “cultural” reputation in France, initially, where they played the legendary St. Tropez gig, warming up the audience before Picasso's play, “Le Désir Attrapé Par La Queue.”

The self-deprecating Wyatt finds it inconceivable that anybody should feel nostalgic for the first Softs. “We were just a bunch of posers, who couldn't play as well as Mingus or any of our heroes.”

All the same, the said “posers,” after, admittedly a line-up change or two, became the first (and to date only) rock band to be invited to play the Proms, were accepted by the British jazz scene (toured with the front line of the Keith Tippett Group in the 1969, played a residency at Ronnie’s in '70), and radically changed rock music throughout Europe, being the inspirational source of a zillion Continental jazz-rock outfits. (Wyatt: “I can't say that I feel particularly proud about that.”)

And Robert's extra-Soft Machine activities were mostly the kind of gigs that will constitute rock legends in years to come.

Can you imagine what an astonishing buzz it must have been to play a significant role in Keith Tippett's mammoth Centipede venture, for example…

And Wyatt was featured on Syd Barrett's “The Madcap Laughs,” arguably the most controversial singer-songwriter album yet.

Robert recalls the sessions: “I thought they were rehearsals! We'd say ‘What key is that in Syd?’ and he'd say ‘Yeah.’ Or, ‘That's funny, Syd, there's a bar of two and a half beats, and then it seems to slow up, and then there's five beats there,’ and he'd go ‘Oh, really?’ And we sat there with the tape running, trying to work it out, when he stood up and said ‘Right, thank you very much’.”

Then came Matching Mole, recording a brace of fine albums… in short, a career a lot of musicians would be proud of. Not Wyatt.

|

|

“I regret almost every second of my professional life. There's hardly a minute on any of those old albums that I can listen to without wincing. Y'know, there's so many bright ideas there, but there's more confusion.”

Early last year, Robert Wyatt managed to fall out of the third floor window of a Maida Vale flat during the course of an exceptionally exuberant party. He broke his back, and put himself out of action for 12 months and is now rather more restricted in his mobility, being confined to a wheelchair.

Curiously, the net result of what must have been a very traumatic period of his life is that Robert seems more in control of his artistic situation than before, despite being unable to play drum kit, which was, previously, pretty much his raison-d'être.

Now forced to concentrate more on singing, at which he was always exceptionally adept, Robert's also got further into keyboards which had hitherto been a hobby, and something he wouldn't have considered doing on stage “unless I got very, very drunk” as he once put it.

Now his keyboard playing is improving, rapidly.

“My keyboard playing, I think, is going to improve just in time to take over from my voice. Limb by limb I'm disintegrating. I can't play drums any more, and, as I smoke 60 cigarettes a day, the singing’s obviously going to dry up in a couple of years, and as the alcoholic poisoning takes over I won't be able to write songs any more, and I'll be left a pathetic zombied figure sitting in front of a piano.

Shortly after no doubt, the paralysis will reach my hands, and finally when all my faculties are gone, I'll become a critic and join you on the Melody Maker.”

Still, with the top half of Robert Wyatt currently operating at something close to peak performance, the wide spread of activities in which he's immersed himself this year is singularly impressive. First, there was a contribution to Phil Miller's song “Calyx” on the debut Hatfield and the North album, and later, a series of gigs with an augmented version of that delightful ensemble, in which situation Robert sang some vocals and percussed enthusiastically on timbales, cymbals and conga.

A role, in fact, he was to repeat at the celebrated Kevin Ayers Rainbow gig in June, alongside the likes of Eno, John Cale and Nico.

A nervous solo gig at the Mal Dean benefit at the ICA Cinema followed, since which time Robert's released the “Rock Bottom” album to unanimous critical raves (and some chart success), done some sessions for the new Eno album, got an enthusiastic audience off at a filled-to-capacity Theatre Royal “solo” gig, and, latterly, taken to doing telly shows to promote “I'm A Believer,” this year's best single so far.

Top Of The Pops was apparently a rather harrowing experience, despite stalwart mimed support from Nick Mason, Dave MacRae. Andy Summers, Fred Frith and Richard Sinclair, while a second attempt for Granada's new Forty Five show, incorporating the soundless services of the complete Hatfield plus Frith, fared more comfortably.

So, from all this running around, can one deduce that there's a possibility of a Robert Wyatt Band hitting the M1 in the not-too-distant future?

“No.” (pause). “No, absolutely not. I'm not being responsible any more for half a dozen other people's food and rent, and the constant compromise of having to present whatever I've got simply because roadies haven't had anything to eat for two weeks.

If I stop working now, I can just sit about for a year if I want and have a think, something that you're never free to do with a band. You have to continually present very substandard stuff for purely economic reasons of keeping the band together.”

Live gigs per se, with a band or otherwise, are going to get the chop. There's some he says, that you can't turn down, the Mal Dean benefit being one of them, but outside worthwhile causes, bread alone won't entice Wyatt back on to the boards. Basically, it seems that Robert is keen to eliminate the element of chance almost completely from his music.

He declined the Hyde Park freebie this year, for example, where he was to have performed with Henry Cow and Slapp Happy, because there was insufficient time for rehearsal and he wasn't interested in jamming, and he's reluctant to get into improvised singing duets with Richard Sinclair when he works with Hatfield. “I can work out my bit, you see, if I know what notes and chords the group are playing, but I don't know what Richard's going to sing.

It might be effective, sure, but I think music can be a lot more than just effective. I think they are right notes and wrong ones. I'm not into chance operations at all. In fact, I'm not interested in any kind of procedure for its own sake.

I'm not interested in groups for their own sakes. I think they're all just mechanisms people apply to themselves in the hope that the result will be beautiful music.

"I’m interest in them only if they work.”

Is this a changed viewpoint, though? After all, improvisation played a large part in the music of the Softs and Matching Mole, and all that experimentation with Symbiosis seemed very much a raving exploration of free music for its own sake.

“Ummm… Well, I've always had this problem right from the time I started playing music. Right back to schooldays, actually, and the Wilde Flowers. I've always worked with two kinds of musicians —some that were into improvisation as a process, and some that weren't. And I've always kind of played the devil's advocate to all of them. Y'know, talking about Cecil Taylor to Dave Sinclair and taking the exact opposite stance with some jazz musician.

All I'm saying really is that any kind of procedure can become a prison, and when that happens, watch out. It can happen just as easily in free jazz as in any other kind of music.

Y'know… Learning to play your instrument faster than anybody else in the world might liberate you… It liberated Charlie Parker, for example. But on the other hand, you've got someone like Keith Jarrett, who, for all his virtuosity can't quite reach the heights that Monk used to.”

Strange, really. For all Robert's enthusiasm for contemporary fashion and an all embracing love for music that can take in Steve Harley, Roxy, Boz Scaggs the Pointer Sisters and whole post-Canterbury mob without any apparent discomfort, there's nothing that really gets him going like his old jazz heroes.

“Yeah, that's the truth. Often when I'd just been to a big deal rock concert somewhere I'd wind up down at Ronnie's listening to five middle-aged guys blowing their hearts out and realise that, yes, I actually liked this a lot more.

For all me name dropping, it's the old record collection, Mingus and Miles that's got it all for me. Why don't you turn to the Ronnie Scott feature, readers?”

|