| |

|

|

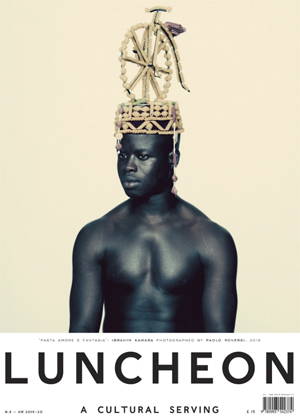

Robert

Wyatt and Alfie Benge - Luncheon - N. 8 - Autumn - Winter 2019-20. Robert

Wyatt and Alfie Benge - Luncheon - N. 8 - Autumn - Winter 2019-20.

ROBERT

WYATT

AND

ALFIE BENGE

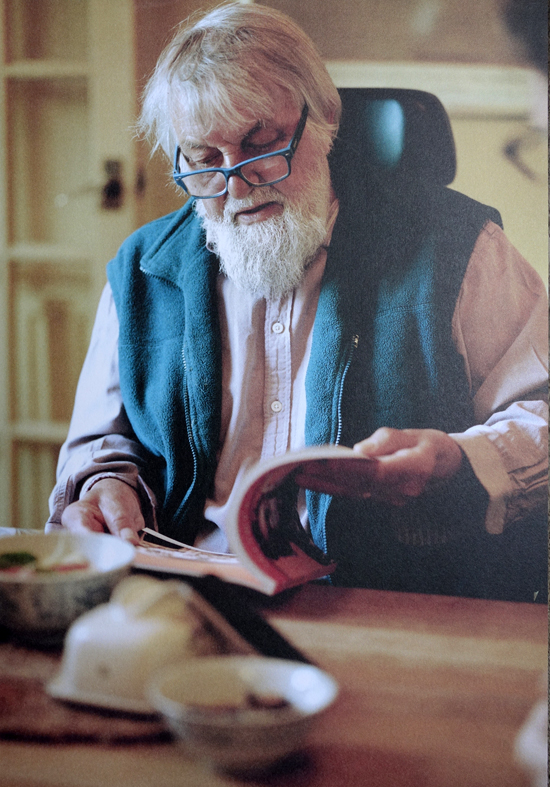

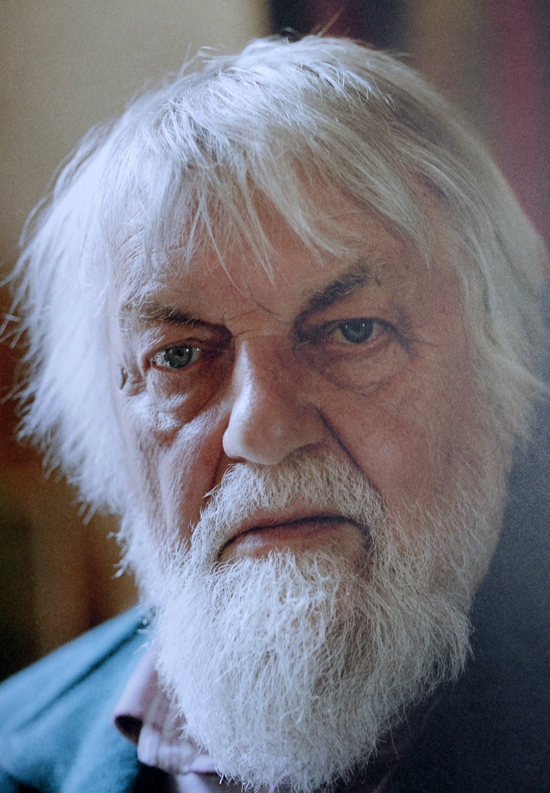

By MARTIN CLARK

Photographs by

KUBA RYNIEWICZ

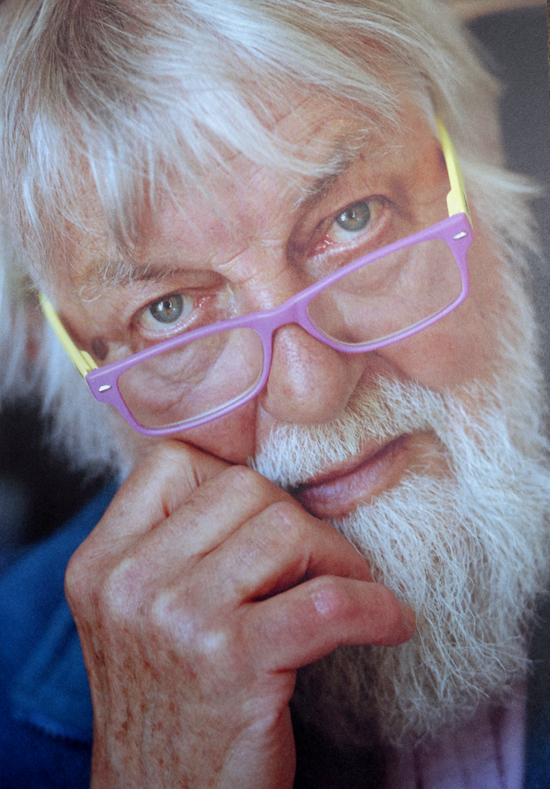

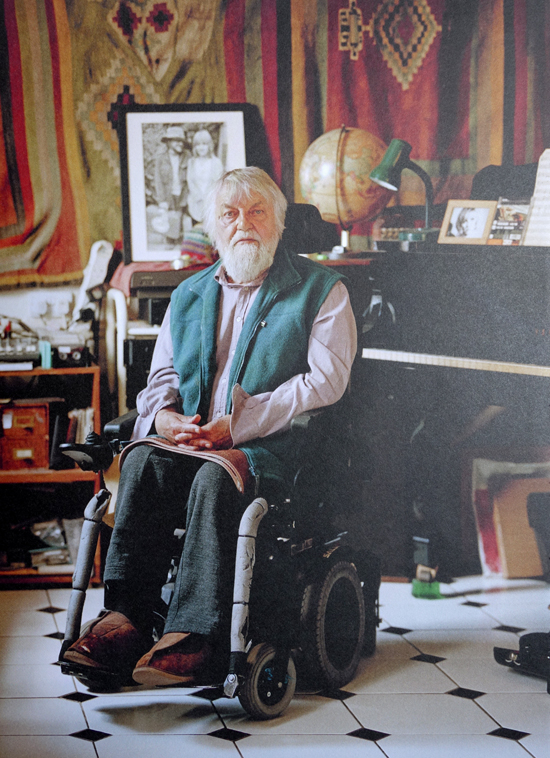

Robert Wyatt is a musician and was a founding member of legendary British rock bands Soft Machine and Matching Mole. Since an accident in 1973 in which he was paralysed from the waist down, he has focused on his solo career, which has now spanned more than 40 years. He has collaborated with artists including Syd Barrett, Brian Eno, Bjork and Hot Chip and has released 13 studio albums and numerous EPs and singles. Martin Clark, Director of Camden Arts Centre, Luncheon's editor Frances von Hofmannsthal and photographer Kuba Ryniewicz took a train to Lincolnshire to have lunch in the home of Robert and his wife, Alfreda (Alfie) Benge, who has produced the artwork for all of his albums since 1974. Over a delicious fish pie cooked by Robert's friend and neighbour Jane Vincent, they discuss Robert's life, music and close working relationship with camera shy Alfie. Martin Clark is Director of Camden Arts Centre, London. Previously he was Director of Bergen Kunsthall, Norway; Artistic Director of Tate St Ives; and Curator of Exhibitions at Arnolfini, Bristol. He is an avid record collector and in a previous life worked in record shops, club promotion and as a DJ in Sheffield. He has been listening to Robert Wyatt for 25 years.

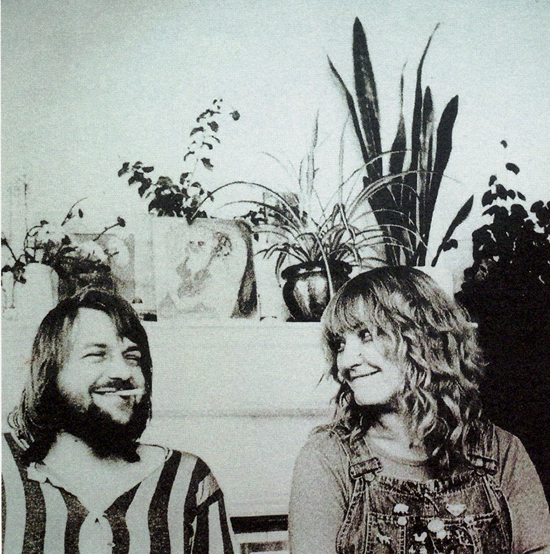

MARTIN CLARK: It's very nice to be here Robert, thank you for having us for lunch. I know Alfie is going to join us later, but I wanted to start by asking about your relationship with her, both personally and creatively. It's a partnership that has spanned more than 40 years now. How did you meet?

ROBERT WYATT: Well, actually, she knew some of my family before I knew her. I'd been married before and had a couple of kids, and she knew them. But when I first really took to her, we were in the Roundhouse, I think; I might have been playing, or in the audience. And I was wandering around in the back, and a lot of people were doing this kind of dance... I can't do it now - a hippy, waving arms about thing. And there was this one girl - not dancing at, or to, anybody -just doing all this little footwork stuff, tch, tch, tch, and I was enchanted by this person. I thought, 'Blimey!' So, that's how we met. I think I said, 'Hello'.

MARTIN: What year was that?

ROBERT: It would have been late... oh, 1970?

MARTIN: Was she at art school then?

ROBERT: No. She was teaching film part-time, had made a film for the BBC about the Royal Academy and worked at IBM helping produce films. She'd also recently worked on dialogue for a Robert Altman film and was doing various freelance jobs too. She'd been to three art schools - painting at Camberwell, typography and graphics at the London College of Printing, and film at the Royal College of Art. Ten years altogether. She'd loved to have stayed on at art school forever.

She switched from painting because at Camberwell in the late 1950s, pure colour, which she always like using, tended to be looked down on. It tended to be browns and greys. She was doing these beautiful paintings and a teacher suggested, 'The colours would be okay if you were Eastern European.' She said, 'Well, I am', which shut him up. But she thought perhaps graphics would suit her better.

MARTIN: Did she know your music at that time? And how interested had she been in music over the years?

ROBERT: Alfie's actually contributed so much to my music since we've been together, I think of it as our music anyway... But even before our work together we were able to talk about everything for hours and hours. I could tell early on that this could be an endless conversation. I was interested in similar things to her - things she read and knew about -politics, music art ..

MARTIN: So you were interested in art as well?

ROBERT: Very. In fact, when I was a teenager I assumed I'd become a painter. That was my thing. We had art books at my home near Dover, in Kent. You know, modern art - all the usual suspects - and I just got lost in that, and I started trying to paint. I think my hero was Paul Klee, but I also liked a lot of the Futurists and De Chirico, that sort of thing. And another book we had, which I haven't seen since: a great, thick, fat book of Van Gogh drawings, just black-and-white things.

MARTIN: His drawings are amazing.

ROBERT: What I find interesting is that, at the time, people thought, 'These paintings are so modern - I can't stand it!' But now they just seem so sweet and old-fashioned, partly because of what they're of, the subject - never mind how it's done. It's very hard to think that those Impressionists were revolutionary at the time.

MARTIN: Its true. And it's become a cliché now of course, but there's a great quote from Wyndham Lewis that I always remember when I'm thinking about this. He said: 'The artist is always engaged in writing a detailed history of the future, because he is the only person aware of the present.'

ROBERT: I've always been interested in the idea of the avant-garde, and there are various words related to that, some of which are pejorative, like 'trendy', 'ephemeral', but also 'cutting edge'. I'd take 'avant-garde' back to the original meaning of the word - it actually means the front end of an army. But the thing I don't like about the connotation, especially in terms of the music I was involved in, rock and roll, is that it fancies itself as rebellious or dangerous.

|

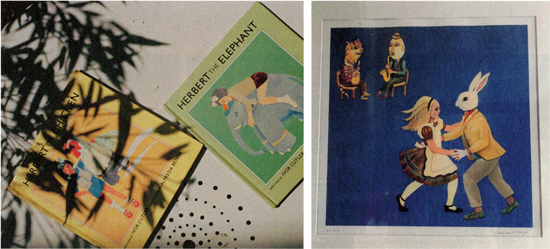

Record covers from left to right: Shleep 1997, Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard 1975,

for Dennis and Ronnie. Courtesy of Domino Recording Co. Ltd.

|

I'm not at all hoping to be either of those things. What avant-garde means to me is seeing the beauty in things that people might not have noticed before. That's all. I'm not trying to get at anybody.

MARTIN: It happens with art as well. People think modern and contemporary art is all about trying to shock, trying to make something outrageous or provocative for the sake of it. But that's not what most artists are trying to do. They are simply trying to say something real and true, but in a way that is free of the received ideas or languages of the past, that somehow avoids disappearing into a kind of familiarity or bourgeois idea of good taste. So it may shock people because it's unfamiliar, but eventually it all gets assimilated - it usually takes a generation.

ROBERT.- I remember, Hendrix, when he did 'The Star-Spangled Banner' and was quizzed on television about it - 'Why did you make this ugly noise out of it?' - he said, 'I thought it was beautiful.'

MARTIN: Did you stop making paintings?

ROBERT: My parents let me draw and paint things on the wall and all that stuff- but I didn't paint on canvases. It was expensive, for a start. I painted on old doors and bits of hardboard, and I thought, 'Blimey. This is it.' But then, when I was 16 or so I went to art college and heard this tutor say to some gloomy students, 'I'm afraid you've got to learn to draw.' Oh fuck, I thought. But the great thing about that time was... I thought, Okay, where don't you have to be able to do anything? Beat music! If you're a drummer or a singer, you really don't have to learn anything. You just sit down and do it, or you open your mouth.

MARTIN: So, your route into music was through beat and rock and roll?

ROBERT: Playing it.

MARTIN: And what about jazz?

ROBERT: I would listen to loads of jazz, simultaneously with painting - but it seemed impossible to play. I just thought they were magicians. I couldn't see how it was possible to do what they were doing - especially between the late 1940s and the late '50s - they were dazzling. So, I traipsed around; saw Charles Mingus live, twice. It was a golden era. The best concert I ever saw in my life was Coltrane playing with Eric Dolphy. It makes me cry to think of it. It was so beautiful.

I always liked playing drums, and I had a couple of drumming lessons. But they don't really apply - if its proper jazz technique no one will hear you in a rock and roll band. It's all crash, bang, wallop.

MARTIN: Did you see that amazing BBC documentary on Ginger Baker?

ROBERT: I did! He's a monster, but he's absolutely right. He's the proper drummer and the others don't really know what they're doing. I have to say that, and I didn't even like rock music. I saw him when he was playing with The Graham Bond Organisation at LSE - he was stonking.

MARTIN: He was playing in these massive rock bands with Eric Clapton and Steve Winwood and Jack Bruce, but all he really cared about was being taken seriously by the jazz drummers and African musicians like Fela Kuti...

ROBERT: That's right. Art Blakey ducted with him eventually. He may have been a frightening geezer, but he was a master, he had a feel.

MARTIN: Getting back to you and Alfie - she made the artwork for all of your solo albums, from Rock Bottom (1974) onwards. And those sleeves feel so intimately connected to my experience of your music over the years. I guess it's something we're losing now, with streaming and Spotify and whatnot, that thing of holding the sleeve in your hand while you listened to the record, almost living inside it for days and days. Were those paintings Alfie used for the artwork things she had made already, were they around the house or in the studio?

ROBERT: No.

MARTIN: So she made them specifically for the record sleeves?

ROBERT: She did. I wouldn't call them collaborations, but she knows the music backwards because she's had to hear it being done. She was with me all the time during recording, so she could pick up on images in the songs that someone at a record company, someone in the art department, might not have had the time to do.

MARTIN: Was she making her own work outside of that?

|

|

Herbert the Elephant and Herbert the Chicken, written by Ivor Cutler,

illustrated by Alfreda Benge (both Walker Books, 1984) |

ROBERT: She'd studied art, but when we met her trajectory was going to be in film. But she didn't like the way the film industry worked and she didn't like being censored. She was doing a thing for IBM about the Sixties and they took [the parts about] the Black Power movement out - not suitable for showing to IMB South Africa. And then, fortunately, I came along and broke my back, so she said, 'I'm not made for the real world, I'll retire and look after you instead.' Anyway, after that she thought she could use her skills in painting and drawing - that this was something she could do here at home. She didn't really like the psychedelic record covers of the era. I know she thought she would deliberately do the opposite.

MARTIN: They have such a beautiful relationship to the music - a simplicity and depth and naivety and absurdity, and a sort of surreal, childlike charm - but there is an edge to them too. But for me your music has a very visual quality already. You can talk about a lot of music like that of course, but it's not just the images and characters that are conjured up through the lyrics or the song titles; there's also something about the way your songs are constructed. There's a sort of blocky quality to music - these drones in the background, like flat blocks of colour, and then these figures that are the melodies that sit on top of them, set against the ground. And I think Alfie's paintings work a bit like that as well.

ROBERT: I think in pictures. I listen in pictures. And so there does tend to be a landscape, which will be the chord sequence. There do tend to be things on it, which will be instrumentation; and there will be people in it, which is the voice. Composers like Duke Ellington and Charles Mingus are very pictorial, they take you places. I like that.

MARTIN: The other thing about them is the lyrics. Alfie writes as well, doesn't she?

ROBERT: The last half of everything I've done, and all of the things I've done here, she's written at least half my lyrics. Partly because I'm writing more music than I could think of words for.

MARTIN: So, for you it starts with the music?

ROBERT: Yeah, but even then - like, I had a little tune, te de de de te de de duh (sings), and I thought, I don't know what that is. And she said, it's a lullaby. And I said, 'Oh, right!' And she wrote a thing called 'Lullaby'. She was just able to do that. She'd listen to the tune until she heard the words. If the tune is organic, it's often very amenable to speech patterns. They can go together if you allow them to.

MARTIN: Were there any records that you made, perhaps with other collaborators, where you were looking at, or thinking about, other artists?

ROBERT: Visually, you mean?

MARTIN: Yeah.

ROBERT: No, except when I did 'Shipbuilding' [in 1982]. Alfie wasn't particularly connected to the making of that - it was written and produced by Clive Langer and Elvis Costello - but she had just seen Stanley Spencer's Shipbuilding paintings at an exhibition and thought they would be perfect. It turned out they were owned by the Imperial War Museum, who let us see the paintings for free. He was a war artist, and he painted a series in the 1940s called Shipbuilding on the Clyde, all these different panels showing riggers and riveters, all that stuff. So we used that on the single. The song was about the Falklands War.

MARTIN: I'd forgotten you'd used a Stanley Spencer on that sleeve. But it's interesting you mention him, because I was thinking about some of those other neo-Romantic artists in relation to your music, people like Paul Nash, Cecil Collins, John Craxton. I always think your songs have a kind of English pastoral quality. And the lazy interpretation of that is that it's a romantic, backward-looking, sentimental thing; but actually the neo-Romantics used the idea and the image of the English landscape to speak of a much more political, troubled, almost apocalyptic moment - coming out of the First World War with the threat of fascism, the atom bomb, and another war looming. They found a way to collapse the past, the present and the future into their pictures. I think your music is a bit like that - right from your early years with Soft Machine, and your association with the Canterbury Sound. And like their work it's also underpinned by a very radical, working-class socialism and critique.

ROBERT: Well, there are two separate things there: one is that things like Lewis Carroll and Hilaire Belloc and so on are very, very far out. They go a long way - particularly Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. They're pretty fierce looks at how things are run, the absurdity of bureaucrats and the madness of politicians - turning into a pack of cards and all that stuff. There's a lot going on there. But the other thing is about your earlier idea of being ahead or behind. I don't think, really, in chronological time. I think that when you discover a thing, that's when it's new to you. I think it's got something to do with the age you are. In your late teens and early twenties, things hit you; you're ready for them. And that stays with you. You can enjoy and appreciate things after that, but the things that really mean something to you, they hit you at that time - and it can be anything. It can be old English churches, it can be Bach, it can be jazz. So, when I was a schoolboy, in the late 1950s, what I was looking at in those art books was early 2oth-century stuff, but it was revelatory, it was dazzlingly new to me, it was like the paint was still wet.

MARTIN: Your music is like that for me. It somehow speaks really immediately, in the absolute present, as well as drawing on something much more timeless. Some music sounds so much of its time - it can still sound great when we listen to it now, but it's very easy to place it or date it. But your songs aren't like that; they seem to exist in this other sort of time. Frances and I were talking on the train here this morning about just that kind of moment - and the first song of yours that each of us heard.

FRANCES VON HOFMANNSTHAL: The first song that I heard was'Pigs... (In There)'(1986).

ROBERT: (Chuckling) John Peel used to like that one.

FRANCES: I love that song so much! I think I've listened to is 945,000 times.

ROBERT: Funnily enough, it was more or less totally improvised. It just came out exactly as you might

think it did -just thinking about it. What the fuck

was that?

MARTIN: It's like a picture again, isn't it, or a movie.

It's so visual. You can see the whole scene when

you're listening to it, the landscape, the farm...

ROBERT: The music just came out, and then I found

this drum machine device... it's no particular

rhythm, it's actually random, but the beat stays the

same. I thought, that'll do - you know, just three

chords, add a bit of olive oil, a squeeze of lemon...

(Martin laughing)

FRANCES: I thought you couldn't cook!

ROBERT: I cannot cook to save my life! That's why

my friend Jane Vincent has made us this fish pie. I

just had to do the salad! Alfie said, just chop up some

tomatoes and onions and some of those green leafy

things, put olive oil and lemon on it - so I did that.

You don't have to eat it.

FRANCES: Where were the pigs?

ROBERT: A long, low, flat farm in Wiltshire. My older

brother - my half-brother and his wife - lived there,

and she used to take us about. You hardly notice it,

the structure, because it's so low to the ground. And

I thought, what on earth could you keep in there? It's

not like you can store grain in it. So I just asked him

what on earth it was for.

MARTIN: Pigs! In there?!

FRANCES: My children and I, we've listened to it so

many times!

ROBERT: I'm very honoured. I'm very pleased.

FRANCES: And 'Soup Song' (1975). They've made a

little stop-frame animation to that one, about all the

ingredients! I'll have to send it to you.

ROBERT: I'd love that! I was a vegetarian as a child

- but not by principle. It sounds posher than it is. It

basically means bread and butter sandwiches with

sugar poured on top - not healthy, nothing noble.

Cornflakes and bananas and bread; Horlicks, boiled

eggs, things like that. I always think eggs is the

politest way to intervene in an animal's life cycle.

(Laughter)

MARTIN: Did you record those songs here in this

house?

ROBERT: No - I do work here, but I'm not technically proficient; I need a good engineer. I have recorded bits and pieces here, something that's got a feel, that I can take into the studio - but no, I go to a studio.

MARTIN: There is a kind of intimacy to your records; they feel very immediate, very close. Is that a deliberate thing, to take those - almost like sketches - into the studio, and then not overproduce them, not overdo them? To keep that immediacy, that simplicity.

ROBERT: I do overproduce them, but... Dolly Parton said, 'It takes an awful lot of money to look this cheap.' (Laughter) Well, it takes a lot of hard work to make it sound as straightforward. They are actually very, very worked. Somebody said to me once: 'What I like about 'Shipbuilding' is you just sang it from the heart and that was it - in one go.' But it wasn't like that. It was a lot of work.

I've thought a lot about the craft of singing. I listen to other singers and hear what they do. I wanted the songs to be [like] how I talk, because that's going to be the easiest to sing. I wanted it to sound like you almost couldn't tell which came first, the words or the tune. That was the thing I was aiming for. In fact, over the years, working with Alfie, that really became the thing. She started out listening to my tunes and coming up with words, and then eventually she'd come up with the words, and I would add the tunes.

MARTIN: I sometimes think of your songs as a kind of folk music. Not so much the sound but the directness and clarity, and the authenticity of your voice. And there's also the strong political and social aspect of the lyrics.

ROBERT: Well, a lot of folk people have done my songs - The Unthanks... a whole bunch of them. But it's also to do with acting. I really like Robert Mitchum - but he just says the lines; he just says the words. I find that so much acting is over the top; over-emoting, in one way or another - sadness, anger. That happens in songs too. I feel that, sometimes, people acting out songs are interfering in some way between you and the song. The thing is the song. So I thought, I don't want to sing like that. I never try and put anything across - it's got to be in the music.

The music has got to be solid enough. And then the words have got to be solid enough. If you get the music right, and the words right, it should just work. It's really a non-thing that I'm doing.

MARTIN: I talk to painters, and for them, often, the thing is knowing when to stop. How not to do too much. I did a show with a painter recently, and she was talking about the problem of pushing a painting too far, not being able to press a button and go back a couple of stages like you can in Photoshop. In the end, she said that the paintings were finished when the truck pulled up outside the studio to pick them up for a show.

ROBERT: Well, actually, I think I do know, in the end. What I'm looking for is something that, in a parallel universe, would be a living thing. I want a tune to be alive in some way - an organic thing. When I'm writing something, that's what I pursue. You can do a really nice chord pattern or a nice sequence of notes, or a nice rhythm, but on their own they're just ingredients - it's not yet anything, actually.

MARTIN: You've said very publicly that you're retired. And I know Alfie has a problem with her eyes, so she finds it difficult to work...

ROBERT: Yeah. [Hans] Arp said he never finished a painting, he just stopped. I thought, I'm having that! So yes, I've stopped. And Alfie, she's having a rest too, she's Tweeting now. Alfie wasn't able to join us for lunch but we caught up with her later in the afternoon.

MARTIN : I asked Robert about this earlier, but I want to ask you as well: what was your relationship to the music? Would you listen to those records and then think about the artwork, or was it more coming out of your interests and your own work?

ALFIE: I was present at every note of every recording. I mean, obviously, because I was Robert's carer - so, wherever he was, I was. And music was always there. Things would occur to me when it was being recorded; I'd just get an image, I'd do some scribbles. Some were more difficult than others. Some had subjects, like Nothing Can Stop Us (1982); Rock Bottom. But Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard (1975) didn't have a subject - that was me in the studio, and I kept drawing a bird-man and a cow-woman. So they sort of emerged. Old Rottenhat (1985) was very political, it was hard to pick any image, so I just painted while listening to the music, and this abstract thing came out.

MARTIN: That's my favourite sleeve: Old Rottenhat. I think it's fantastic. And I can think of sleeves that I've seen since, and designers, who've clearly been influenced by it.

ALFIE: Cuckooland was also hard to choose an image for, there's so much variety in the subject matter and music. Robert has no normal musical notation. He does diagrams and notes for himself, which get added to during recording. I just watched what he was doing and based the cover on pages from his - ever-changing notebook and added a bit of colour here and there.

MARTIN: And what about Shleep (1997)?

ALFIE: He recorded that just as he came out of a really, really extreme depression and hadn't slept for months. He got over the hump - that bit where he's going to kill himself, into... when it's not plain-sailing, but he was suddenly able to sleep again. So, that's why we called it Shleep. A lot of the titles are mine as well.

MARTIN: He said you wrote a lot of the lyrics. I knew that you wrote lyrics, but I didn't know that you wrote so many of Robert's.

ALFIE: Since he started using them on Dondestan (1991), about half of the lyrics on each record are mine.

MARTIN: And when you were writing, was it because you thought they might end up as lyrics for Robert?

ALFIE: No, he had a thing about the music always coming first. The chords matter; the words don't. He was never going to write things to words - never. And so I wrote things. I wrote a diary, and out of the diary came little poemy things. We made a little book of them and just put them in a drawer - in 1983 or '84. Then, in 1990, he got them out because he couldn't think of any words. I think they really helped him to open up new musical possibilities.

MARTIN: He was able to hear the music in them?

ALFIE: Yes - so, things like 'Sight of the Wind' [from Dondestan]. I think it culminates in 'Cuckoo Madame', which, I think, is musically quite sophisticated. I think it comes from responding to the rhythm of the sentences, which is less predictable because they hadn't been written for music.

MARTIN: I asked him how you two met.

ALFIE: I was 32 or 32, and he'd left Soft Machine. I'd seen Soft Machine, but I didn't know him then. I had a boyfriend. During the rip-roaring Sixties, I spent most of my time with drummers, as an official drummers' moll. One of the drummers was a pick-up in a speakeasy when I was about 27. It was very dark. Anyway, he came for the night and then wouldn't go away. It turned out he was only 17. It was a few months before I could get rid of him - but, in the meantime he'd made friends with a friend of mine, and he eventually hooked up with Robert's wife. So I got to know Robert's wife and his son through... (Laughing)

MARTIN: ...this 17-year-old drummer!

ALFIE: So, I knew them first. [Robert and I] didn't take much notice of each other at first. He had kind of glamorous women at the time. Purple hot-pants, I seem to remember! And usually a bit taller than him. I was still wearing high heels back then. When we met we were the same height; I stopped the high heels! But I didn't assume he was anything to do with me - I mean, my drummers were jazz drummers (apart from the speakeasy guy!), jazz drummers who knew what they were doing.

MARTIN: (Laughing) Proper drummers.

ALFIE: Serious people. Proper people. I'm joking. He was a very serious drummer! But I just kind of got to know him, and I thought, 'He's quite intelligent, I quite like that.' One day, he rang up. I think it

was Pam, his wife, who encouraged him, because

she thought I was probably a good idea. He wasn't

having very much fun... I think his women were

a bit glamorous, but a bit difficult. She thought I

might be better for him. So he rang up, and that

night I already had a ticket to go to the Rainbow

[Theatre] to see The Kinks, so I said, 'Would you like

to come along?' So we went to see The Kinks, and he

stayed the night, and that was it, forever and ever.

His excuse, at first, was that he had to go through

my record collection.

MARTIN: (Laughing) That took some time!

ALFIE: I had a lot of records that girls didn't have at

the time - sort of boys' records.

MARTIN: So that was immediately attractive!

ALFIE: Well, he just wanted to hear them. We had

our ups and downs. We were together a year and a

bit before the accident. After that it was, do I take

this on? For me there was no question - and if so, it

would probably be an idea to get married, so then we

know where we are, and he knows where he is, and

all of that. I've been really lucky.

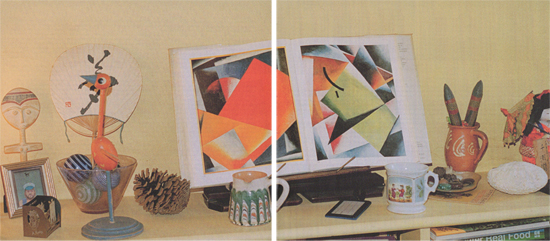

MARTIN: And your studio is upstairs here in the

house, above Robert's.

ALFIE: Yes, but I don't use it anymore. It's complete

and utter ...it's like one of those films on the telly

about hoarders. (Laughter) It's disgraceful, I'm so

ashamed of it.

MARTIN: It's a studio! It's allowed to be. But tell me,

what were the things that you were driven by when you were making your work?

ALFIE: The job in hand. Nothing else. The task. It's the same with everything. It's the same with making anything: What is it, this thing? With a cover you want to represent the person, you the subject. You try to make it a precious object. And you need a certain amount of information. I'm very hot on adding information. All the sleeve notes are by me. I think people want to learn a bit.

MARTIN: Were you asked by any other musicians to do sleeves and artwork?

ALFIE: I've done a couple for Fred Frith. And Annette Peacock; Gorky's Zygotic Mynci. Not a lot; I mean, you couldn't call us 'prolific'. We just about did the job. I find it hard to call myself anything, really. I illustrated a couple of books for Ivor Cutler, like Herbert the Chicken. I think I've got a musical ear - so I loved lyric writing. I loved doing it to the music because of all the little nuances that you have to think about - like, does he want an 'oo' or an 'ee' here, in which case, do I have to change that word, because it really would sound nicer if it was 'oo'. I enjoyed that much more than painting when I started doing it. I've done some lyrics for Bertrand Burgalat as well, a French musician. But in the end, I think Robert and I go well together. His stuff is abstract, and mine generally always has pictures - so, without the pictures, this might be a bit... I mean he's very good; I really like his stuff- but I think both of us together, it works, just by accident.

|