| |

|

|

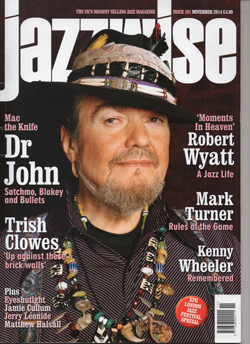

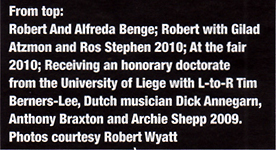

I'm A Believer - Jazzwise - Issue 191 - November 2014 I'm A Believer - Jazzwise - Issue 191 - November 2014

|

|

|

|

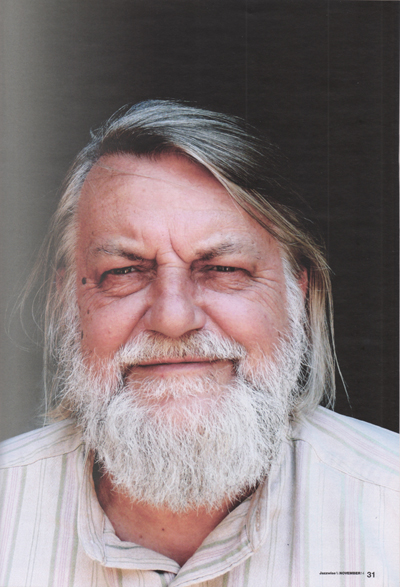

Throughout Robert Wyatt's prolific, often profound, musical life, a deep love of jazz has been the conduit between his own celebrated jazz-rock legacy with Soft Machine and Matching Mole, his individualistic, highly imaginative solo career and the deep world of jazz music and musicians he has become involved with along the way. Inspired by its inherently rebellious, left-leaning nature, jazz has also fuelled his political beliefs as well as his music's magpie-like eclecticism, while his distinctly melancholic, engagingly forlorn vocal style has won him a legion of die-hard fans outside the mainstream. Marcus O'Dair's newly published book - Different Every Time: the Authorised Biography of Robert Wyatt - explores his jazz inspirations and continues here as Wyatt reveals how jazz has been with him from childhood onwards

I first interviewed Robert Wyatt for a national newspaper podcast in 2008. When I later contacted him to ask whether he would let me write his biography, he left a voicemail in response. He agreed to the proposal, he said, for two reasons. I hadn't asked whether Syd Barrett was mad. And I had asked about jazz. Wyatt is not a jazz musician in any strict sense of the term, and his influences stretch from pop (sometimes mischievously mainstream) to South American folk. Yet jazz, in particular, has been fundamental to his half-century of making music.

Born in Bristol in 1945, Wyatt was introduced to the music of Fats Waller and Duke Ellington by his dad, George; an interest in more contemporary, avant-garde artists, meanwhile, came via his older half-brother, Mark. He was soon bashing away on pots and pans, before moving onto a full trap kit. Through the poet Robert Graves, a family friend, Wyatt met Ronnie Scott in the early 1960s, and was soon visiting the saxophonist's eponymous club in Soho to watch the likes of Charles Mingus and Sonny Rollins. "As an atheist," he declares, of Mingus, Rollins and their ilk, "they're the nearest to Gods I've ever had."

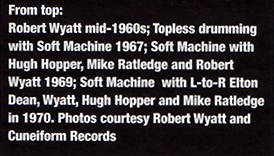

This secular reverence has informed almost Wyatt's entire output, even as far back as 1963. That was the year he emerged, playing Beatnik-style jazz with the Daevid Allen Trio (fronted by Allen, who had previously lodged with Wyatt's family in Kent, and featuring former schoolmate Hugh Hopper on bass). The Wilde Flowers, with whom Wyatt played during the mid-1960s alongside the likes of singer-songwriter Kevin Ayers, were a very different act, aimed more squarely at the dancefloor. But even then, Nat Adderley and Herbie Hancock numbers began to creep in alongside the Small Faces and Kinks covers.

It was from 1966 that Wyatt began to achieve prominence, as drummer and sometimes vocalist with Soft Machine -alongside Allen, Ayers, and keyboard virtuoso Mike Ratledge (another former schoolmate). The band originally played soul-infused psychedelia but, during gigs, their 'freak-out' sections drew on jazz. As Soft Machine's line-up evolved, as it did at an unusually fast pace, the jazz element increased: there was a power trio era, featuring Hugh Hopper and reminiscent of Tony Williams, John McLaughlin and Larry Young in Lifetime. Then the band borrowed Keith Tippett's horn section, including alto saxophone and saxello player Elton Dean, and moved further towards jazz-rock fusion. Soon Soft Machine became entirely instrumental. Wyatt - odd one out due to his continuing interest in song, as well as in alcohol - departed in 1971, but not before the group had supported the likes of Roland Kirk, Thelonious Monk and Miles Davis.

|

|

Wyatt's next band, Matching Mole, began with a definite move towards song, but jazz arrived with the recruitment of New Zealander Dave MacRae, whose rippling electric piano was reminiscent of Joe Zawinul. In his various extracurricular

projects, meanwhile, Wyatt was already playing with a number of other jazz musicians, including Lol Coxhill, Keith Tippett and South African exiles including Mongezi Feza.

Paraplegic from 1973, when he fell from a fourth-floor window, Wyatt was obliged to musically reinvent himself. No longer able operate hi-hat or bass drum, he morphed from singing drummer into a singer who also played keyboards, percussion and, more recently, trumpet and cornet too. Rock Bottom, released in 1974 and regularly cited as one of the finest albums of all time, showcased this new mix of jazz - Gary Windo on tenor sax and bass clarinet, Mongezi Feza on trumpet - with the dour surrealism of Scottish poet Ivor Cutler.

A similar mix has been evident on Wyatt's subsequent releases: 1975's Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard featured Mongezi Feza and saxophonist George Khan, and a Charlie Haden number appeared in the track list. Nothing Can Stop Us, released in 1982, featured bassists Peter Ind and Ernest Mothle and trumpeter Harry Beckett - and featured a version of 'Strange Fruit'. Cukooland, which was shortlisted for the Mercury prize in 2004, found Robert namechecking Parisian jazz haunts Le Chat qui Peche and Rue St Benoit (home of Club St Germain) and covering Antônio Carlos Jobim. Comicopera, released in 2007, featured bossa nova vocalist Monica Vasconcelos and steelpan/vibraphone player Orphy Robinson. And so on.

'Shipbuilding', a top 40 hit in the wake of the Falklands War, drew on jazz too. Clive Langer, who co-wrote the tune with Elvis Costello, had been inspired by Wyatt's version of 'Strange Fruit'. "'Shipbuilding' is an odd song in that sense," explains the producer. "Pop people think it's jazz, and jazz people think it's pop."

A number of jazz musicians have been particularly important to Wyatt over the years: players of the calibre of Evan Parker, Annie Whitehead and Gilad Atzmon appear more than once in his discography. As a guest musician, meanwhile, Wyatt has worked on several occasions with composer/pianist Carla Bley and composer/trumpeter Mike Mantler. Along the way, he has worked with everyone from Steve Beresford to Larry Stabbins. As recently as 2012, to the enduring delight of drummer Clive Deamer, Wyatt popped up on the Get The Blessing track 'American Meccano'.

Much of Wyatt's favourite jazz is as old as he is. "In 1945, the year I was born, Miles Davis made his first record with Charlie Parker," he reflects. "As much as I love everything beforehand in jazz, from Duke Ellington back to Louis Armstrong, I feel that these are my people; this is where I come in. And it is, actually, where I come in. Almost to the month, from the moment I'm born, stuff happens. I can trace my life through it, and I still do."

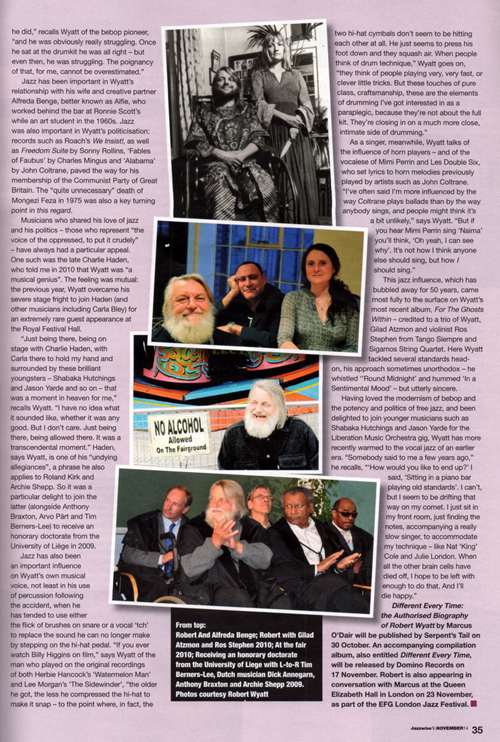

As a fan, however, Wyatt's tastes extend both forwards and backwards from that point. He is currently going through "a period of almost weepy nostalgia" for British trad: Acker Bilk, Ken Colyer, even Temperance Seven. Yet he also keeps up with newer artists. When he curated the Southbank Centre's prestigious Meltdown festival, back in 2001, Wyatt's line-up included Orphy Robinson and Matthew Shipp as well as John Surman, Jack DeJohnette, Keith Tippett and the veteran Max Roach. "That was virtually one of the last gigs he did," recalls Wyatt of the bebop pioneer, "and he was obviously really struggling. Once he sat at the drumkit he was all right - but even then, he was struggling. The poignancy of that, for me, cannot be overestimated."

Jazz has been important in Wyatt's relationship with his wife and creative partner Alfreda Benge, better known as Alfie, who worked behind the bar at Ronnie Scott's while an art student in the 1960s. Jazz was also important in Wyatt's politicisation: records such as Roach's We Insist!, as well as Freedom Suite by Sonny Rollins, 'Fables of Faubus' by Charles Mingus and 'Alabama' by John Coltrane, paved the way for his membership of the Communist Party of Great Britain. The "quite unnecessary" death of Mongezi Feza in 1975 was also a key turning point in this regard.

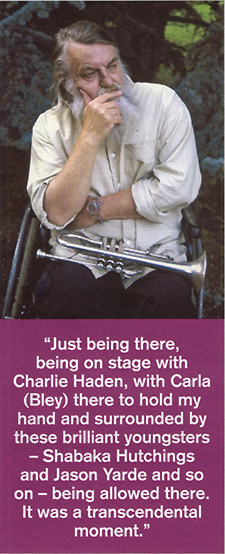

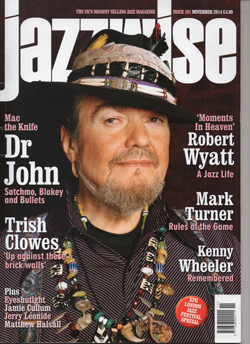

Musicians who shared his love of jazz and his politics - those who represent "the voice of the oppressed, to put it crudely" - have always had a particular appeal. One such was the late Charlie Haden, who told me in 2010 that Wyatt was "a musical genius". The feeling was mutual: the previous year, Wyatt overcame his severe stage fright to join Haden (and other musicians including Carla Bley) for an extremely rare guest appearance at the Royal Festival Hall.

|

|

"Just being there, being on stage with Charlie Haden, with Carla there to hold my hand and surrounded by these brilliant youngsters - Shabaka Hutchings and Jason Yarde and so on - that was a moment in heaven for me," recalls Wyatt. "I have no idea what it sounded like, whether it was any good. But I don't care. Just being there, being allowed there. It was a transcendental moment." Haden, says Wyatt, is one of his "undying allegiances", a phrase he also applies to Roland Kirk and Archie Shepp. So it was a particular delight to join the latter (alongside Anthony Braxton, Arvo Part and Tim Berners-Lee) to receive an honorary doctorate from the University of Liege in 2009.

Jazz has also been an important influence on Wyatt's own musical voice, not least in his use of percussion following the accident, when he has tended to use either the flick of brushes on snare or a vocal 'tch' to replace the sound he can no longer make by stepping on the hi-hat pedal. "If you ever watch Billy Higgins on film," says Wyatt of the man who played on the original recordings of both Herbie Hancock's 'Watermelon Man' and Lee Morgan's The Sidewinder', "the older he got, the less he compressed the hi-hat to make it snap - to the point where, in fact, the

two hi-hat cymbals don't seem to be hitting each other at all. He just seems to press his foot down and they squash air. When people think of drum technique," Wyatt goes on, "they think of people playing very, very fast, or clever little tricks. But these touches of pure class, craftsmanship, these are the elements of drumming I've got interested in as a paraplegic, because they're not about the full kit. They're closing in on a much more close, intimate side of drumming."

As a singer, meanwhile, Wyatt talks of the influence of horn players - and of the vocalese of Mimi Perrin and Les Double Six, who set lyrics to horn melodies previously played by artists such as John Coltrane. "I've often said I'm more influenced by the way Coltrane plays ballads than by the way anybody sings, and people might think it's a bit unlikely," says Wyatt. "But if you hear Mimi Perrin sing 'Naima' you'll think, 'Oh yeah, I can see why'. It's not how I think anyone else should sing, but how / should sing."

|

|

|

This jazz influence, which has bubbled away for 50 years, came most fully to the surface on Wyatt's - most recent album, For The Ghosts Within - credited to a trio of Wyatt, Gilad Atzmon and violinist Ros Stephen from Tango Siempre and Sigamos String Quartet. Here Wyatt tackled several standards head-on, his approach sometimes unorthodox - he whistled "Round Midnight' and hummed 'In a Sentimental Mood' - but utterly sincere.

Having loved the modernism of bebop and the potency and politics of free jazz, and been delighted to join younger musicians such as Shabaka Hutchings and Jason Yarde for the Liberation Music Orchestra gig, Wyatt has more recently warmed to the vocal jazz of an earlier era. "Somebody said to me a few years ago," he recalls, '"How would you like to end up?' I said, 'Sitting in a piano bar playing old standards'. I can't, but I seem to be drifting that way on my cornet. I just sit in my front room, just finding the notes, accompanying a really slow singer, to accommodate my technique - like Nat 'King' Cole and Julie London. When all the other brain cells have died off, I hope to be left with enough to do that. And I'Il die happy."

Different Every Time: the Authorised Biography of Robert Wyatt by Marcus O'Dair will be published by Serpent's Tail on 30 October. An accompanying compilation album, also entitled Different Every Time, will be released by Domino Records on 17 November. Robert is also appearing in conversation with Marcus at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London on 23 November, as part of the EFG London Jazz Festival.

|

|