| |

|

|

Robert

Wyatt - Bomb N° 115 - Spring 2011 Robert

Wyatt - Bomb N° 115 - Spring 2011

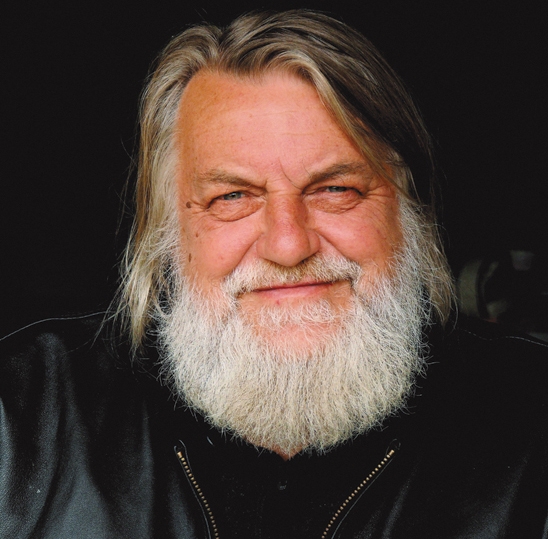

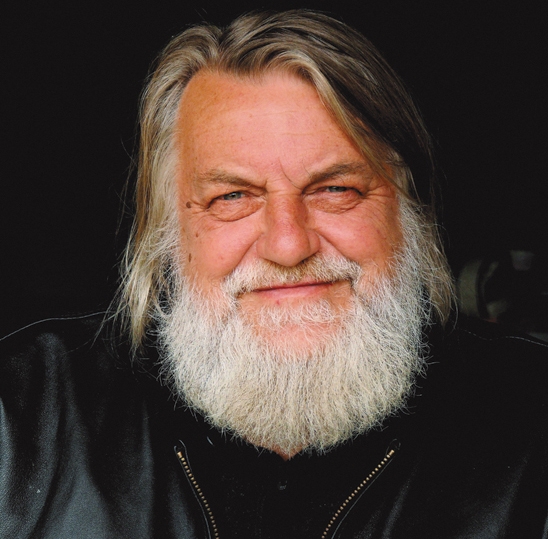

ROBERT WYATT by Shadia Mansour

| |

Robert Wyatt’s story is as compelling as the endlessly imaginative music that it yielded. Like that of the best songwriters, his work is a world unto itself, instantly recognizable, not least of all due to his high, quavering vocals and almost cubist approach to lyrics. Involved in every avant-garde of British music since the ’60s—from prog rock to punk and postrock—Wyatt began his career as the drummer and vocalist for the Canterbury band Soft Machine, a seminal prog-rock outfit heavily into jazz time-signatures and modal drift. In 1973, Wyatt fell from the fourth-floor window of a friend’s home, becoming paralyzed from the waist down. While recuperating, he began work on what would become Rock Bottom, a haunting album that relied heavily on keyboards and multitracked vocals as opposed to the full-band workouts of his earlier music. This is a sound that Wyatt has cultivated to this day, one composed of complex blends of pop, jazz, and world music in miniature, a la Brian Wilson’s “pocket symphonies” even, though more immediate and British in their foregrounding of Wyatt’s sophisticated and eccentric sensibility.

|

|

A better comparison might be to the concise, wildly surreal work of arty punk bands like the Swell Maps or The Homosexuals, groups with an obvious debt to Wyatt. By the early ’80s, Wyatt had begun recording for the underground label Rough Trade, releasing a series of beautiful singles that reflected a newly found, fervent political awareness. In the ’90s, he became something of a hero of underground musicians with the albums Shleep (1997) and Dondestan (Revisited) (1998) receiving rave reviews in publications like The Wire magazine and the sadly now-defunct Popwatch. His work since that time has been clever, restless, and typically brilliant. His latest record, For the Ghosts Within, a collaboration with Ros Stephen and Gilad Atzmon, is his first since 2007’s politically charged Comicopera. Wyatt is an international treasure whose work, though highly political, never ceases to function as musical art of the highest order. His wit, both sonic and lyrical, is boundless.

Recently, Domino Records reissued Wyatt’s entire catalog, introducing his work, which sounds as current as it did the day it was recorded, to a new generation of ears. Wyatt and British-Palestinian rapper Shadia Mansour, who guests on For the Ghosts Within, communicated over email about the development of political consciousness, the song-writing process, and how an understanding of history informs one’s creative practice.

—————Clinton Krute

|

|

Robert Wyatt Good morning, Shadia. First, thank you for taking time out from what is probably a pretty active time in New York. I hope talking by email isn’t going to make it too difficult.

Shadia Mansour Salam, Robert! Thank you for making this happen. Congratulations on your latest masterpiece For the Ghosts Within. It’s an honor for me to be a part of it—it’s inspirational to listen to. I want to apologize for my delayed response; I just got back from Detroit and did not want to answer your email in between shows.

You have been a loyal supporter of the Palestinian people and have expressed (metaphorically) your solid and principled stance against anything apartheid through your music for years. What has been more effective: music or activism?

RW I came to politics via my love of an earlier Black American idiom, jazz, which led me to the antiapartheid movement. I was born in 1945, when the relieved assumption was, I think, that Fascism, experienced as institutionalized racism, and the colonialist assumptions that depended on such hubristic delusions were totally discredited. But by the 1970s it became apparent to me—thanks, in part, to meeting Alfie, now my wife, who was much more politically inquisitive than I had been—that the victors of World War II, having neutered the competition, were at it again, inventing more devious rhetoric to cover their (our) traces. But I was always steeped in my parents’ quasireligion: art. The rising tide of racism in England was simply ugly: racial pride in itself is natural enough, but the racist mindset promotes racially exclusive elites, and that’s what gives me cultural claustrophobia. The art I loved most—jazz—was the fruit of the feverishly fertile cross-pollination of extremely diverse communities interacting in the United States. Racism was clearly a serious threat to the regenerating nourishment that the art I loved fed on. Not just jazz, of course. By then, there was no “either/or” about it: music and politics merged into one stream running through my life.

To me, a musician can be a witness, a more subjective one than a political activist. It’s not for us to say what use we are to anybody, really. We can hope to encourage the wind behind the sails, but we are not the sailing ship. There are musicians and artists who generally feel disengaged from the human conflicts around them—some great ones, too. And there are those of us who feel impelled to participate in some way. Among painters, for example, Matisse worked his way through the rise of Fascism like a distant monk, his focus on living entirely through painting as an end in itself. By contrast, his friend Picasso got engaged publicly in the resistance, most famously with his painting commemorating the victims of the Fascist bombing of Guernica. I do think that Picasso’s aesthetic activism was a valuable contribution to the war effort. But he had to live in exile from his beloved Spain to do it.

As for us musicians, it varies so much too, doesn’t it? What we’re trying to do in the first place… In my case, my exasperation about the cowardly evasiveness of our mainstream press drives me to think that if people in general knew more about history they’d be more likely to demand more honorable governments. I don’t have any illusions about the effect of my making simple references to under-reported events and the people involved in them in my songs. For example, the sabotage of the democratically elected, secular government of Iran by the US and British governments in the early ’50s, or the collusion by France, Britain, and the US in helping establish Israel’s nuclear-weapons industry. If mainstream political writers aren’t bothering to mention these things, who will? But I’m more convinced about your value in this respect than I am of my own.

I was raised in an “art is the fruit; the rest is the tree” sort of home. My father had been a pianist—he played Mozart, Debussy, adaptations of folk music, and 20th-century music, including Thomas Waller and Duke Ellington. But, professionally, he was what was called an industrial psychologist. My mother was a journalist and BBC producer/broadcaster. Most appealing to me as a boy were their art books: from Cézanne and Manet to Braque, Picasso, Chagall, and Paul Klee. And, crucially, I was stunned by what I saw at museums and art galleries bringing us non-European artifacts from Mexico, the Pacific, Near-and-Far-Eastern Asia—the world beyond.

|

Photo by Alfie Wyatt.

There’s a nice quote from Auden, something like “We are all recruits of our time,” and although in a decent world, I think I could happily live my life like a pleasure-seeking child, I find that the ugliness of so much reality puts my personal search for pure beauty in a rather inadequate light. So I reach out to others not because I think I can change reality but simply to find comfort out there, the warmth of fellowship in adversity. It sounds a bit pretentious, perhaps, but it’s very simple, really: I do what I do because that’s all I can do.

I’m interested in the bridges you cross, not only by being bilingual, but also, for example, between rap culture, Black Roots, and your Arabic-British life, the inspiration of Lauryn Hill [a former member of the Fugees] and Palestinian survivors. Was it the sound or the political implications that hit you first?

SM If I’m totally honest, I’d have to say I was primarily driven by politics, especially with what had gone on and was going on in Palestine and the rest of the Arab world. I got into music at an early age, singing at the peaceful rallies I attended, protesting against the daily abuse of the Palestinian population. And I got into Arabic hip-hop around the same time that 9/11 happened. That event changed the face of what “Arab identity” represented and gave birth to what I describe as a newly dignified Arab. A new form of resistance and determination was blossoming in the West, and I was part of the early days of that change. I found discipline in Public Enemy’s music, their form of resistance was intellectual, and they managed to speak in a universal language. Hip-hop was a shelter that became a community and which has now become almost a religion in its own right.

RW BBC Four did an open-university documentary series about schools in Syria, a country with communities of Palestinian refugees. In one of two episodes focusing on Palestinian schoolchildren, a couple of girls were fighting for the right to rap to cautious older Palestinians. How easy is it for you to reassure more traditional Arabs of your relevance?

SM I would want them to be reassured of the importance of equality and respect between males and females, first and foremost. How can we ask for a free Palestine if we are not free from each other? Having said that, Arabic hip-hop is still young and is a lot to digest for the more conservative figures in our community. With reason and patience we can get to that point in which we can give each other a chance to use our voices in a productive and effective way without holding ourselves back.

RW Rap liberated the language used in songs—there’s been Black American song for years, but rap allowed street vernacular, as well as the real concerns of “the street,” a big new space. Do you find that by extending song into “speaksong” your Arab vocabulary is somehow liberated?

SM Two of the most crucial elements in hip-hop, in my opinion, are what you are saying and how are you saying it. Arabic hip-hop has played a huge role in bringing the Arab vocabulary down from its high horse and more level with ordinary people who want certain things to be “told how it is.” I think we have also liberated ourselves in the process.

RW Is there any tradition within Arab poetry or song/music that connects with rap? Rap in Arabic sounds so natural.

SM Absolutely, I learned about the beauty of our culture mostly through song and poetry. If you take a look back at sixth-century pre-Islamic poetry, you will notice many familiar elements which hip-hop shares today: resistance, pride, passion, knowledge. Our roots are a part of who we are, even though we are not always aware of it.

What is your approach to writing lyrics, Robert?

RW Two ways: if the tune comes first, I try to imagine words that seem to belong to it. Occasionally, I have some words that seem to need music. I have no reliable approaches or methods for this. It just has to come to me; I work on the assumption that if I do what feels right instinctively, there’ll be an organic coherence to it. I don’t work from plans, theories, manifestos. They’re retrospective. There is no explanatory equivalent to making what I do.

You have achieved something rather rare, a joined-up working life; your vocal talent matches your message organically. Many artists struggle with this: the (apparently contradictory?) pursuits of trying to be a true witness of real life “out there” and the impulse to make magic through the freedom of the imagination to invent. Do you consciously struggle to reconcile the truth (which can be ugly) and beauty?

SM Anyone who is not actually living under the circumstances they preach about will be taken less seriously than if they were. I have borne witness to the truth and have tasted the realities of the Palestinian struggle for self-determination. You only need to cross an Israeli checkpoint to know what sheer humiliation feels like, or wake up to house demolitions in Arab neighborhoods in Jerusalem, or visit children in youth centers in camps without electricity or clean water. But more importantly, truth is truth, no matter who spreads it. The bottom line is, it’s not about us artists, it’s not about where we are from, it’s bigger than all of us…It’s the message and the impact.

RW Tell me about your performance with Lowkey for the Norman Finkelstein events. How did the writer and activist find you?

SM Norman Finkelstein’s support of my and Lowkey’s work has only motivated us more. We were invited to perform alongside him for the launch of his book This Time We Went Too Far in New York last May. It was a very diverse crowd, but nonetheless, very welcoming. I have to be honest: I never thought for one minute that I’d ever see Mr. Finkelstein waving his hands side to side and rocking out to Arabic hip-hop.

How did you discover Arabic hip-hop and what inspired you to add it to the song “Where Are They Now”?

RW It was Gilad Atzmon [an Israeli-born reed-playing musician; antiracist and anti-Zionist, now a Londoner], who for a while had been working on the little ditty “Dondestan” (an imaginary state whose name comes from the Spanish for “where are they/you”) that I’d done on an eponymous solo record.

His inspired idea to ask you to bring it to life gives For the Ghosts Within an extra dimension, especially following Tali Atzmon’s [Gilad’s wife] title track. We talk about rap, but what terrific singing you both come up with. Not for the first time, I have a lot to thank Gilad for, including his work on my previous couple of records.

SM How was it to work with Gilad?

RW Lovely. For the Ghosts Within is an extension of a project that Ros Stephen and Gilad had worked on before, based on an old Charlie Parker with strings record. They wanted to extend the format with voices. It’s their project and I’m simply a guest. I’m very happy to have been asked! Gilad keeps me on my toes—he’s a fast worker and doesn’t sit around wondering what’s next. It’s great for me because, not doing live work, I miss that sense of urgency. He seems to live every second to the hilt, but unlike some action men, he’s constantly updating his philosophical take on things.

SM How do you feel about the current state of the music industry today (dating back to when you began)? Do you think artists and musicians are starting to speak out more? Which direction do you see it going?

RW I don’t know enough about the state of the music industry to speak much about it. There’ll always be music, and people listening to it, so I don’t fret too much about it! I’ve only remained connected to the “industry” via a few specific individuals who work in the independant part of it, who for some reason empathize with what I’m up to and try and make it possible for me to operate. (Without them I’d be sunk.) My lack of academic refinement means I’m not really eligible for most arts funding, so I’ve had to make a living via the music marketplace; but my dealings have been with these few sympathetic people—the “industry” itself has always seemed some distant, foreign thing.

Inevitably I get to hear recent music, but I don’t search for it. My record collection hasn’t changed a lot in 50 years. It’s more a museum than a fashion display. I’m basically fueled by the ghosts within… I really admire a young Palestinian couple known as Tashweesh: Ruanne Abou-Rahme (film) and Basel Abbas (soundscapes). I witnessed them not long ago; Ruanne’s shifting, semiabstract images work perfectly with Basel’s multilayered sound effects. And I like the American guitarist Mary Halvorson. There’s a wittiness in her approach that reminds me of my jazz hero, Thelonious Monk.

SM The birth of hip-hop was hugely inspired by jazz. Do you think there is still that bond between the two?

RW My missus, Alfie, suggested to me that the blues and such folk idioms are closer ancestors of rap than jazz, although you could say jazz liberated notes like rap liberates words—the way they can tumble free of their formal structures. My favorite art usually has that tension between geometry and chaos.

>> L'interview sur le site de Bomb

|