| |

|

|

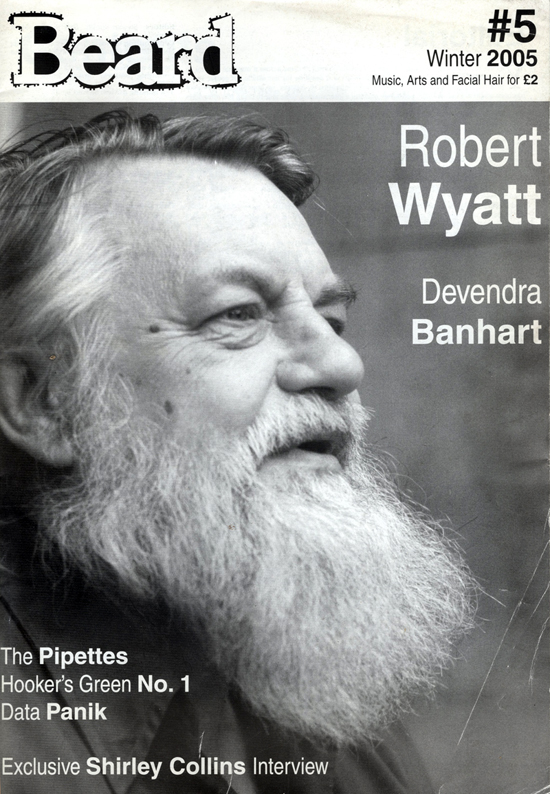

Robert Wyatt - Beard - #5 - Winter 2005 Robert Wyatt - Beard - #5 - Winter 2005

Robert

Wyatt

Words : Neil Jaques

Photos : Mark Connelly

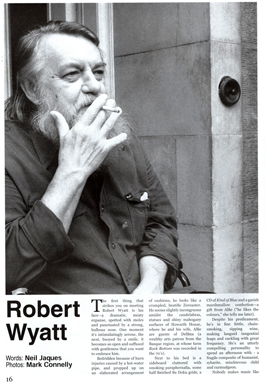

The first thing that strikes you on meeting Robert Wyatt is his face - a dramatic, meaty expanse, spotted with moles and punctuated by a strong, bulbous nose. One moment it's intimidatingly serene, the next, buoyed by a smile, it becomes so open and suffused with gentleness that you want to embrace him.

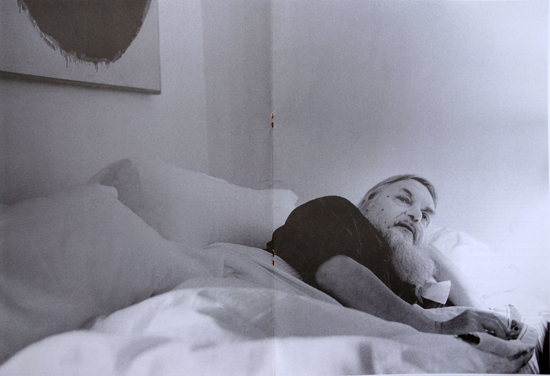

Bedridden because of burn injuries caused by a hot-water pipe, and propped up on an elaborated arrangement of cushions, he looks like a crumpled, beatific Zoroaster. He seems slightly incongruous amidst the candelabras, statues and shiny mahogany surfaces of Howarth House, where he and his wife, Alfie are guests of Delfina (a wealthy arts patron from the Basque region, at whose farm Rock Bottom was recorded in the 70's).

Next to his bed is a sideboard cluttered with smoking paraphernalia, some half finished Su Doku grids, a CD of Kind of Blue and a garish marshmallow confection - a gift from Alfie ("he likes the colours," she tells me later).

Despite his predicament, he's in fine fettle, chain-smoking, sipping wine, making languid tangential leaps and cackling with great frequency. He's an utterly compelling personality to spend an afternoon with - a fragile composite of humanist, sybarite, mischievous child and curmudgeon.

Nobody makes music like Robert Wyatt. Since he became a paraplegic in 1973 the former drummer with the effeminate singing voice has hewn a musical vision that defies the parameters of musical logic. With a dizzying amalgam of jazz, soulful ascetic prog, the avant-garde, melody and unpretentious poetry, he always threatens to make no sense. But somehow, and with a disarming directness, always does. He's never released a bad album (some of his best have come in what most would consider the twilight years of an artist's life), and he has never sounded anything less than startlingly relevant. You would have a hard time convincing him of this though.

"I'm not particularly tuned into my times," he says, eventually, following a lengthy attempt at positioning himself in the contemporary musical landscape.

"Except you always know what the latest sylph-like black ladies are up to," interjects Alfie.

"One of the joys of music is that it is beyond pinned-down sex.

I feel that in music I have the right to be any fucking sex I like!"

|

"Yeah, I do like black ladies," he retorts, flashing her a seraphic smile. "Sylph-like. Preferably in very short skirts - I think they're terribly good!"

"In fact, the only LP I really sang along with all the way through was a Dionne Warwick record. And Dionne Warwick had a very long skirt so I'm y'know, very broad-minded about skirt lengths!"

I'm half-way through asking him if that could account for the femininity of his own vocals, when he stops me short:

"One of the joys of music is that it is beyond pinned-down sex. I feel that in music I have the right to be any fucking sex I like!"

As an adolescent, Robert Wyatt Ellidge's mindset was, in his own words, "unreconstructed 1940's Harlem". A jazz obsessive, he was able to hum labyrinthine solos verbatim, and spent hours beating out Jimmy Cobb rhythms on a drum kit constructed from a typewriter, clothes rail and an old ammunition box. He even gave illustrated jazz lectures for anyone who would listen during school lunch breaks.

He's wary of calling his upbringing bohemian, but his home - a 14 room Georgian home (known as Wellington House), populated by a cavalcade of lodgers - was at least somewhat anomalous against the staid backdrop of 1950'$ Canterbury.

One of the Wellington House lodgers was an Australian beatnik called Daevid Allen (briefly a member of Soft Machine, and later, Gong). Allen had hung out with William Burroughs, smoked a lot of pot and owned a sizable collection of jazz records. He influenced Robert immensely, turning him on to the Beats, and, crucially, introduced him to George Niedorf, an American jazz drummer, who offered drumming lessons in lieu of rent.

Predictably, school paled by comparison.

"I just hated it, provincial English grammar school life. I really hated it. It was absolutely dismal," he says angrily.

"I should have been sent to a secondary modern and learned carpentry and would have been happy as you like. My big mistake was to pass my 11 plus. I should have just failed it and I think I would have been a happy adolescent."

"I just thought I don't want to be in this world. I just don't want to do any of the things they're teaching me."

It was an existential crisis that led to a suicide attempt at the age of 16, using Allen's stash of sleeping pills. He left school with no qualifications. Instead, he followed George Niedorf drifting around Europe, at one point staying with his mother's friend Robert Graves in Majorca. On his return to England he became involved in some brief, though inspired, tomfoolery with Canterbury band The Wilde Flowers (alongside Hugh Hopper and Kevin Avers) and by 1966, he was Soft Machine's singing drummer.

Soft Machine's lunatic blend of jazz, homegrown British whimsy and Wyatt's propensity for a good tune had them pegged as the ultimate cult band, earned them a place on tours with Hendrix ("Courteous, considerate and witty") and opening stints for Miles Davis ("I think rock n' roll made him really cross. He felt, y'know, 'who are these kids?'"). Nevertheless, it's not a time he recalls fondly.

"I found that, to me, the 6o's thing was a bit ostentatious. I mean, I got drunk and did it but I could see why people didn't like it," he says flatly.

"People are surprised about that, they always think I'm a sort of classic 60's person. I'm not: I was a so's person and then I became a 7o's person. The 60's were just the thing in the middle between childhood and adulthood. To me it's just excruciating adolescence, that's how I'd sum it up. Deeply embarrassing. "

Objectively he's got nothing to be embarrassed about—he'd become one of the most imaginative drummers around (a single listen to Why Are We Sleeping dispels any doubts), an accomplished songwriter and an integral part of two indisputably essential recordings (Soft Machine Vols. I & II).

Towards the end of the decade, however, Wyatt's idiosyncratic vocals and pop sensibilities were being marginalised in favour of a purer jazz sound, and his heavy drinking habit had begun to annoy the stoic Ratledge and Hopper. He recorded his first album, the much overlooked End of an Ear (1971), as an outlet for his suppressed creative urges, emblazoning the sleeve with the legend "Out of Work Pop Singer Currently on Drums with Soft Machine." After four albums he walked out. Any conversation about those final days is met with uncharacteristic reticence.

"I don't like bands; I think they're too bloke-ish for me. I can't give orders, I can't take orders, so it doesn't leave you much option in a group—you've got to be able to do one or the other and I could never do either," he says, by way of summation.

It was somewhat surprising then that his next move was to form another group, Matching Mole (a cheeky French pun on Soft Machine), who produced two, equally overlooked, albums in their short lifespan. They were about to reform in 1973 when, drunk out of his mind at a party, Wyatt fell from a third storey window, paralyzing himself from the waist down. "This was how the accident went: in order, wine, whiskey, Southern Comfort then the window," he remarked in Michael King's biography, Wrong Movements. His doctor informed him that if he hadn't been so drunk and had fallen more rigidly, he would have been dead.

I feel apprehensive discussing the circumstances surrounding the accident, but Robert is comfortable and candid.

"I'm missing the moderate gene. I don't understand moderation," he says simply.

"My dad, wicked chap, lovely man, used to come out with sayings like 'if a thing's worth doing, it's worth overdoing!' Lovely saying. And I've always thought that. I've never understood this thing about drinking in moderation. I thought, what's the fucking point of that?"

Was alcohol always your vice?

"I stick to the legal drugs. I found a wonderful thing—which is don't worry about breaking the law. You can get completely smashed out of your brain on legal drugs. Just don't worry about it. Believe me, the right combination of serious amounts of wine and brandy and vodka and then a bit of Tia Maria and lots of fags...believe me, you're sailing. You're out there."

He gives a raucous laugh and adds solemnly:

"You have to know where to draw the line. There's this thing called a line, which we have to draw apparently. You just have to know where it is - and I'm crap at that."

Following a lengthy, painful recuperation he recorded arguably his finest work, Rock Bottom (1974). Through a precarious morass of hypnotic drones, Wyatt's uninhibited singing, which at times is reduced to high-pitched yelps and percussive, rhythmic breathing patterns, becomes the sound of expiation, of coping with the aftershocks of paraplegia, and a tear-inducing expression of his love for Alfie (whom he married that year).

There's a dense, dreamlike quality to the sound, lyrics and imagery—a common theme in much of his later work.

"Partly it's a negative thing because my dreams are much more physically active and varied than my waking life can possibly be," he explains.

"I think they're extraordinary little journeys— the stories that happen and all the things you can do....

He pauses, dragging heavily on his cigarette.

"...and find yourself doing and if it's a nightmare, that's alright 'cause you wake up and think, well that's not true! Fantastic! And if it's a nice dream, it's a nice dream. Gravity has gone. Being awake is like you're being anchored and when you're asleep it's like 'anchor's away!' Off you go, just let the wind blow you wherever," he says, making wave-like movements with his hand.

Outside of music, Robert Wyatt is probably best known for his politics. After a fallow period in the late 70's and early 80's, he began explicitly fusing his political beliefs—an ideological strain of communism—with music, releasing the musical call to arms Nothing Can Stop Us (a compilation of overtly politicised covers). He also had his biggest hit with the intensely moving anti-Falklands song Shipbuilding, which was penned especially for him by Elvis Costello and Clive Langer.

These days you're not likely to see Wyatt - still a communist cardholder - handing out copies of The Morning Star in the rain. He's aware of the flaws of socialism but still clings to it as distant, symbolic hope. Talking to him about politics, he doesn't seem as trenchant as before. For instance, he doesn't follow current affairs that closely.

"I don't get my sense of the world from journalism," he says. "I always come up with these crap analogies, but I wouldn't get my knowledge of the oceans from surfers and speedboat drivers.

"I'd get my knowledge of the ocean from deep-sea oceanographers, not from people just endlessly zooming around the waves at the top, which is what I think news journalism is. I am actually interested in the undercurrents, the stream of history. My reference points tend to be more cultural and how people treat each other."

The calmness in his voice comes to an abrupt halt when I mention Blair et al.

"I find that our government is a completely alien collection of horrible monsters," he spits building up a vituperative momentum:

"I scarcely recognise them as being members of the same species - let alone the same country! I just think that we haven't got the hang of this leadership business at all. We keep clinging on to a kind of 'Boy's Own' mentally retarded leadership, like boy scouts charging off into the wilderness to sort out Johnny Foreigner, I think 'Oh, for fuck's sake! I thought we finished all of that in the 19* century.

"My dad, wicked chap, lovely man, used to come out with sayings like 'if a thing's worth doing, it's worth overdoing!' Lovely saying."

|

"I'm just too vain, intellectually vain, to even take much interest really. I think fuck it, there's nothing I can do about it."

What about the responsibility of art?

"I don't think art should have any more responsibility than anything else," he replies, sounding irritated.

"I think it's quite vain of artists to think that they are the engine of anything. There is a relationship between art and politics, but it's a response to politics. I'm not in the business of making people feel bad about being apolitical and I think it's none of my business to tell people what to do at all!"

He stops himself and sighs wearily:

"I say things and read them in interviews and it looks so sort of bleak and I think 'I was only fucking joking!'. I think if you make certain commitments like joining the communist party the automatic assumption is that I must be incapable of levity and there must be some kind of utter solemn groove but it just happens to be...I mean, I looked at all the various analyses of the world and it seemed to me about right, y'know. I read the Marxist analysis and thought yeah, that's the world I recognise. Well, that must be what I am."

What he is when he's back home in semi-rural Louth, Lincolnshire, is a fairly unassuming man. He fills his time with music, ephemeral entertainments such as TV - he's a huge comedy fan, effusively praising everyone from Chris Morris, Victoria Wood, Spaced and "that amazing guy off Green Wing" (Mark Heap) - the occasional drink, and quiet domesticity. He'll

trundle around anonymously, pop into Woollies for Janet Jackson albums ("Some people feel guilty about liking Janet Jackson, not me mate. I think she's terrific"), and socialise with neighbours. Generally, within Alfie's limits, he does what he likes, when he likes.

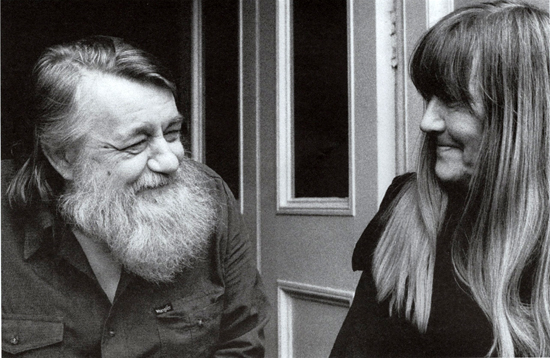

Alfie's influence is inestimable. She designs his album covers, writes some of his lyrics (they've written 20 songs together) and looks after him, loves him and protects him. Without her a combination of procrastination, perfectionism and fear would prevent him from achieving anything. He'd rather listen to jazz all day.

When he first met her she came across like a "Mongolian princess", who didn't throw herself at him like the usual groupies, instead remaining coolly aloof.

"She had a very stately way of going about things. I was dead impressed. She had all these books on politics and stuff and, y'know, she was much better educated than me, reading all sorts of philosophers I hadn't heard of. We'd go a see long foreign films with subtitles. It was a great adventure for me. It's just the best company I've ever had really."

When I ask him to identify the point at which he is happiest, he begins mumbling something vague about finishing a record before he pinpoints the exact moment:

"Drunken evenings with Alfie," he says assertively.

"She doesn't really do it as a habit as I would, but occasionally she does and she remembers all these old songs and gets out her singles starts dancing around to Motown classics or whatever and old jazz records and the brandy keeps flowing and then it gets heavier and heavier and she starts getting out the flamenco and then she gets back to her people and it'll be Polish things [Alfie is of Polish descent] and Neapolitan songs and the candles are burning and I love that. That's the most fun I can think of."

|