| |

|

|

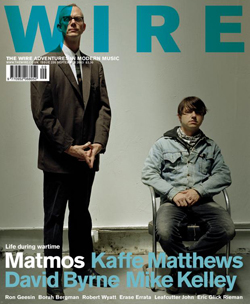

Epiphanies - Wire N° 235 - September 2003 Epiphanies - Wire N° 235 - September 2003

EPIPHANIES

Robert Wyatt learns the value of cheap music from a Ray Charles ballad.

Rabble Rouser : Robert Wyatt

Photo : Keiko Yoshida

Before I can start, there's a caveat... well, two really. One, the conductor Sir Thomas Beecham said that the English don't know much about music but they like the noise it makes. The other is, Gunther Schuller, writing about jazz listeners, talks about the kind of cloth-eared lefties who think that "Strange Fruit" is a good song [Wyatt famously recorded the Billie Holiday song on a Rough Trade single in the 1980s]. I don't feel I'm an authority on music outside of what I know, there's all kinds of stuff about music I don't understand.

I'd been brought up to believe in serious music. For my Dad, most serious was Bartok and Hindemith. He had liked Fats Waller and Duke Ellington before the war, even though he didn't think they were serious music. I did, but my Dad knew they were real music at least, and as I was young, they were allowed. By then I was getting as much out of Gil Evans as I was out of Hindemith, and as far as I was concerned it was just as serious. But at that stage I still accepted the idea that there were intrinsically serious and shallow idioms, and my Dad's thing was that pop music was intrinsically shallow. I'd heard quite a lot of it because my sister had records, and they didn't interest me a lot. So I didn't have a problem with Dad's idea.

Until I came across an LP called The Genius Of Ray Charles. I thought, Genius? How could he be a genius if he's only a popular singer? Clearly a misuse of the word. I was like that. I didn't really have any argument with my Dad. I really liked my parents and I liked what they liked, the art of the 20th century, the surrealists, the dadaists and all that stuff. But with Ray Charles, it was a difficult moment because as far as I can hear, bearing in mind my caveats, Ray Charles singing a ballad, even a soppy one like "Don't Let The Sun Catch You Crying", is as good as Bartok's Violin Concerto or Miles Davis. I knew it was a slushy pop song, just a tune with tinkly cocktail piano, and because it had violins on it, it didn't have any jazz cred. I couldn't even work out what the words were half the time, but I thought, it's an astonishing record, absolutely beautiful. Suddenly any idea of a hierarchy of art crumbled away in my mind, and as far as I was concerned, there was no intrinsically superior idiom.

It was only a small crack in the music listening in the house, but it opened the way for absolutely anything. I could now enjoy Buddy Holly or Beethoven or whatever. After that. I found out I was constantly going against the grain in the sense that every new idiom sets up a hierarchy: good versus naff, quality versus crap, and so on. and on my new trajectory I always seemed to be finding serious, solemn beauty in what was considered naff. Later, when I was making music myself, it was bit embarrassing because we [Soft Machine] weren't playing regular pop music. People said, "This is better than pop music, it is superior." Once again. I could see incipient hierarchies reemerging. like there was this need to have them.

On The Genius Of, one side was big band Ray Charles, "Let The Good Times Roll", things like that, and the other side was strings. Well, the jazz hierarchy at that time had it that the respectable side was the big band lot, the other side was the girls' stuff, and I always liked the girls' stuff. I went to absurd lengths, it now seems, to break this hierarchy. I was into The Bee Gees. Lynsey De Paul, The Monkees, anything. Gary Glitter? Let it roll. Fantastic. I wasn't just asserting something against an old guard but the very new guard as well, which was very busily constructing an intellectual hierarchy, of which we [Soft Machine] were petty princes. It was completely mad and I thought, I have got to deal with this. So I did a Monkees song [in 1974, several years after leaving Soft Machine, Wyatt released "I'm A Believer" as a solo single.]

"Don't Let The Sun Catch You Crying" interested me as well politically. My parents and a lot of their friends on the Left, not revolutionaries, were egalitarian when it came to economic political issues. But in their minds an intellectual aristocracy had replaced the cultural aristocracy that they had relinquished and abandoned. Similarly, as much as the Socialist countries abandoned economic hierarchies in the Western sense, they vociferously embraced bourgeois cultural values and had an almost hysterical fear of popular culture. They were taken with a thing called improving music, improving culture, which is good for you, and naff culture, which is bad for you, and children must be guided away from all these bad things. The more I read about it, I realised that this tendency had been going on for centuries. The church, for example, used to have a problem with rabble music. Organised church music was elevating, and the music of the rabble, when they got pissed, caught sexual diseases and that sort of thing, was the bad kind. The church monitored the rabble with totalitarian verve, intervening constantly to break down the power of mob culture and mob music. Following on from that, you couldn't shock my parents' communist or egalitarian friends by saying. "I don't believe in God", but you could by saying, "I don't believe in Mozart".

Well, I really disagreed with that. The Left missed a trick there, because the idea that serious music was morally elevating took a bit of a battering after the Second World War. What they talked about as serious music, basically, was the music of the Austro-Hungarian empire. Opera, symphony and all the great structures of music gave us the Axis powers, and how morally elevating was that? There wasn't anything wrong with the music, but the claims made for it were ersatz religious claims made out of fear of the mob.

All this came out of listening to Ray Charles, who made it perfectly all right to be a genius and I have clung on to that key assertion nervously ever since. Even so, I hadn't yet finished with hierarchies myself. Before buying a record, which wasn't very often in those days, I went on and on subdividing jazz into participants and innovators and geniuses and not-geniuses. All right, we got the geniuses here: Thelonious Monk, yes; Charlie Mingus, yeah; Charlie Parker, yeah; Duke Ellington, John Coltrane, yes... Ornette Coleman, can I buy Ornette Coleman? Well, OK, for the tunes, yeah?

Of course, I was missing the main event, which was hundreds and hundreds of people playing music and having a fantastic time doing it, out of which come some people with a few diamonds. But genius is in the whole culture, fermenting away in hundreds of different ways and every participant is part of it.

Interview by Biba Kopf. Cuckooland is out this month on Hannibal

|