| |

|

|

Robert Wyatt - Q N°343 - February 2015 Robert Wyatt - Q N°343 - February 2015

|

|

No sooner has Robert Wyatt welcomed Q into his home than he's apologising for the long journey. Since he and his wife Alfie moved to the Lincolnshire market town of Louth more than 20 years ago, he's felt like he's a world away from the heart of the music industry so he greets visitors with a mixture of gratitude and surprise.

"I can't believe Björk was sat where you are," he says, marvelling across his dining table, cup of tea in hand. "We sat and played Sun Ra records. I was truly starstruck. She has magic to me."

The house is as welcoming and characterful as its inhabitants. The walls are decorated with Alfie's designs for Wyatt's album covers and a picture of Che Guevara with a sticker reading "Smoking cures stress". On the mantelpiece near the table there's a ruby wedding anniversary card and a Russian doll of sour-faced former Soviet premier Leonid Brezhnev.

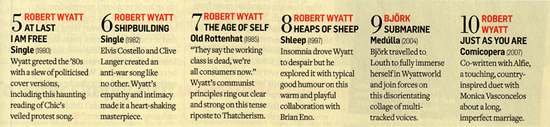

Wyatt's song with Björk, Submarine, is one of several collaborations that he's collated on the second disc of a new compilation called Different Every Time. "I like the sense of being employable," he says cheerfully. "It's reassuring."

A companion to Marcus O'Dair's new authorised biography of Wyatt ("big and thick, like me," says the singer). Different Every Time winds a typically unorthodox path through Wyatt's unique career but still can't do it justice. In the 40 years since an accident confined him to a wheelchair, the former drummer has created a soundworld where surrealist whimsy coexists with fierce political conviction, English eccentricity with globetrotting curiosity, good humour with fathomless sadness, audacious experimentation with pop clarity, a big brain with a warm heart. His friend Brian Eno has compared Wyatt's unmistakable voice to "a poor innocent cast into a complicated world".

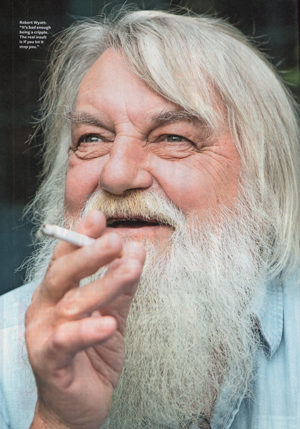

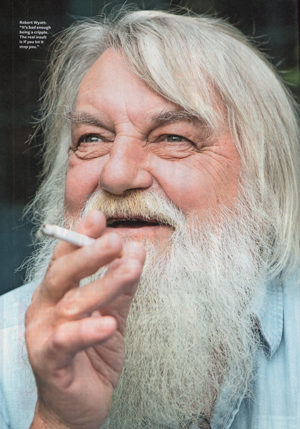

In person, the 69-year-old is as intriguingly paradoxical as his music. Despite his accomplishments, he's modest to the point of masochism. He's effortlessly erudite about anything from Picasso to Palestine, but merrily describes himself as "thick as shit". He projects wisdom and optimism, with a jovial chuckle that convinces you all's right with the world, yet he's suffered from depression and anxiety. You can tell some subjects are still painful from the way he chain-smokes Chesterfields and tugs at a fleecy white beard, which suggests both Karl Marx and Santa Claus. His life has been fascinating but not easy.

"When people say they like my records," he says, "I think, 'If you knew how hard it was to make those records you'd be even more impressed than you are!'"

Robert Wyatt-Ellidge's childhood was both blessed and cursed. His parents, a music-loving industrial psychologist and a freelance journalist, were unusually cosmopolitan for post-war Britain. They took young Robert to continental Europe, schooled him in modernism and jazz, and ran a nurturing, bohemian household: one of Robert's four half-siblings, Julian Glover, is an actor who currently plays Grand Maester Pycelle in Game Of Thrones. "I was never a rebel against my parents," says Wyatt. "I liked them very much."

When Wyatt was 10, however, his father developed multiple sclerosis (he died eight years later), and his enforced retirement meant they needed lodgers to keep their ramshackle Kent house going. Life at a rural grammar school didn't suit him at all. "I know people where education was their introduction to the outside world," he says, thoughtfully puffing away. "Perhaps

for me it was a narrowing down. I got cultural claustrophobia."

He dropped out at 16, the same year his parents emigrated, leaving him to fend for himself with various menial jobs, a failed attempt at painting and "dossing" around Europe, where he got "a real sense of what it's like being a nobody, an alien, and how you're treated." He found his calling playing drums in what he quaintly calls "beat groups". "There was no great weight of historical precedent saying what it should be like," he says. "To that extent I think all British rock music is punk music: fools rushing in where angels fear to tread."

In 1966, after a short spell fronting The Wilde Flowers, Wyatt formed Soft Machine, who became popular with the "heads" thanks to their endless jazz-rock odysseys. Alfie once described them as "too much happening all at once for too long."

"Yeah," Wyatt laughs. "Well, it's a phase to go through. I did get carried away on drums. Every time I had an idea I would play it. I’ve regretted that since. The drummers I listen to now are the ones that leave space."

Soft Machine toured America with The Jimi Hendrix Experience in 1968. Wyatt was drinking with Hendrix when the news broke that Martin Luther King had been assassinated. "We were playing in Newark and Hendrix dedicated a song to 'a friend of mine who just died,'" he says, his voice trembling. "I'm getting tearful now. It was just... fucking hell. They were such a kind bunch. What I liked about Hendrix was he was almost embarrassed by his apparently effortless superiority."

Wyatt, for his part, was embarrassed by the term "progressive rock". His journey as a music fan, from the avant-garde to pop, was the reverse of most prog-rockers'. "My discovery wasn't the obscure or the esoteric. It was the joy of playing for dancers and the idea of music as a service, like a restaurant or a caff. So I always found the [progressive] idea presumptuous. And also there was something vaguely racist in the idea that what Little Richard and Chuck Berry did was rock'n'roll but then it progresses. Well, actually, fuck you! "

Soft Machine burned through members fast and in 1971 it was Wyatt's turn to get ousted by bandmates who hated both his singing and his drinking. He admits he was "getting right out of order" but at the time he was traumatised. "It's amazing how it recurs in nightmares," he says heavily. "It was that sense of having given my youth to developing this thing and then being rejected by it. It was emotionally shattering."

|

|

|

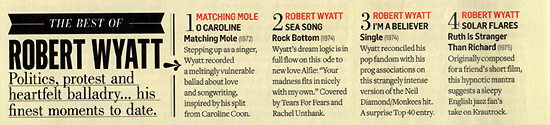

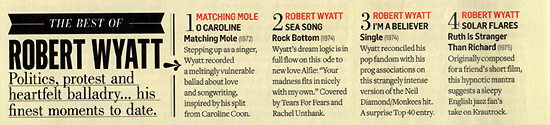

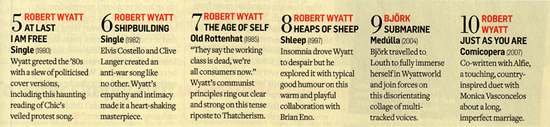

Wyatt formed a new band, Matching Mole, whose name was a barbed pun on the French translation of Soft Machine, and his love life was looking up. After breaking up with Caroline Coon, the artist and activist who inspired Matching Mole's beautiful O Caroline, he met Alfie. Born Alfreda Benge in Nazi-occupied Poland in 1940, she was an artist and aspiring film-maker. Wyatt soon realised she was "the one".

In 1972, the film director Nic Roeg invited Alfie to Venice to work on the thriller Don't Look Now, which co-starred her old friend Julie Christie. Alfie bought Wyatt a toyshop keyboard so that he could compose while she was on set. He thought the Venice songs, inspired by his new love, would comprise the third Matching Mole album but Robert Wyatt has led a life of two halves and the first half was about to come to a violent end.

On 1 June, 1973, Robert and Alfie went to a party at a West London flat. Wyatt proceeded to get drunk and fall four storeys while trying to climb down

a drainpipe. He can remember hearing a distant scream after he hit the ground.

Later, a friend told him, "That was you." Submerged by painkillers for six weeks, Wyatt awoke to learn that he'd broken his 12th vertebra, paralysing him from the waist down, at the age of 28. After three months, he was finally allowed out of bed and began playing the piano in the visitors' room, fleshing out the Venice songs to match the visions in his head. "It's a landscape," he says. "There are rivers spreading out into deltas, there's mountainous bits, there's rough terrain. It's embarrassingly literal."

Wyatt agrees that it's strange that this injury set him back less than being fired from Soft Machine. "Alfie says, 'Robert lives in denial and who'd be so cruel as to knock him out of it?'" he laughs. "There was a pride element. It's bad enough being a cripple. The real insult is if you let it stop you." (Later, Alfie tells me, "I think the one thing missing from the book is the incredible aggravation of being paraplegic. Because he doesn't make a fuss about it, nobody notices.")

On a pragmatic level, Wyatt needed to earn a living and he couldn't drum any more so he became a reluctant singer-songwriter. His Rock Bottom album was released in 1974, on Robert and Alfie's wedding day. Produced by Pink Floyd's Nick Mason, it's an extraordinary piece of work: dreamlike, playful and deeply moving. Mason also produced Wyatt's first detour into the Top 40, a strangely intense version of the Monkees hit I'm A Believer.

Wyatt is a passionate pop fan who watches The Voice and tried to book Hear'Say for his 2001 Meltdown festival. He wanted to make a point with I'm A Believer.

"I was very uncomfortable with having fans who said, Tour music is so much better than all that banal pop music.' It sounds like a socialist thing to say but pop music is the music of the people. It's the folk music of the industrial age. If you don't respect popular culture you don't respect people, in which case your political opinion is of no great value."

Wyatt has always been well-loved.

Friends such as Pink Floyd, Christie and her boyfriend Warren Beatty all offered financial support after the accident, and many more have collaborated with him over the years, including Brian Eno. "Old male elephants who get rejected after a tussle can sometimes form little gangs of their own," says Wyatt. "That's what rogue elephant means. I think me and Brian became rogue elephants. I love him, I really do. He's all heart."

Never a prog-rocker in spirit, Wyatt immediately loved punk ("funny and terrific") and 2-Tone ("much more interestingly politically than anything in the "60s"), and found a new generation of people to work with, including The Raincoats and Scritti Politti. In 1982, Madness producer Clive Langer asked Elvis Costello to help him out on a song with Wyatt in mind and Costello came up with Shipbuilding, a heartbreaking vignette of a working-class community affected by the Falklands War.

When the demo tape landed on Wyatt's doormat, he responded with his usual humility. "I thought, 'What is it they think I do that makes them think I could do this?'" His low-key vocal, which made Langer burst into tears, made Shipbuilding one of the most tender protest songs ever recorded.

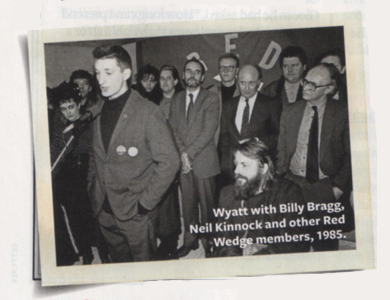

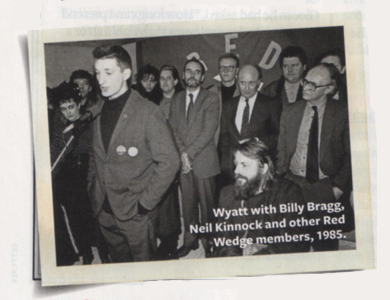

Politics consumed Wyatt during the '80s. He guested on benefit singles such as Working Week's Venceremos (We Will Win) and the SWAPO Singers' The Wind Of Change, composed the soundtrack for an animal rights documentary, joined Labour-supporting musicians collective Red Wedge, and recorded an LP of protest songs, Nothing Can Stop Us. On Matching Mole's Gloria Gloom he had asked, "How long can I pretend that music's more relevant than fighting for a socialist world?" Now he had his answer.

"I had been a leftist musician but I became a singing leftie," he says. Having once believed that art was "the point of life", he now fretted that it was a decadent luxury. "I think I'm going to be worrying about this for the rest of my life," he says. "At worst, I think it's decorative and the more of a sewer society is, the more gloriously distracting the art has to be. That's part of what human inventiveness is - trying to make something lovely out of shit. The world as compost."

He also joined the Communist Party of Great Britain when it was at its lowest ebb. He takes time to explain his complicated reasons for signing up to a lost cause. "It's partly nostalgic affection for the loser," he says. "I couldn't have joined it when they thought they were winning. I wanted to give these ideas a decent burial at least." When

the young modernisers drifted towards what became New Labour, Wyatt stuck with the old guard. "I thought, I’d rather sink in your ship than stay afloat in theirs."'

This period ended with 1991's Dondestan, whose title track called for a Palestinian state. It's a subject about which he is still fiercely passionate, at the cost of some "desolately sad" rifts with Jewish friends. "Nobody's called me anti-Jewish that I know of but there is a sense that you cannot support these people." Years later, a music snob ruined a night in his local pub by playing Dondestan on the digital jukebox and christened this sonic trolling "Wyatting". The staunchly anti-elitist Wyatt was dismayed. "I would never do that. It would be so rude! How could you enjoy it? It would cut you off from the communal thing."

After Dondestan and his move from London to Louth, Wyatt was floored by the most devastating depression of his life. "I had something of a nervous breakdown," he says quietly. "And for once Alfie said, 'Look, I can't deal with this. I’ve done everything I can for you.' It was really bad. I went quite mad from sleep deprivation."

With help from an NHS counsellor, he threw himself into a

new album, 1997's Shleep, like it was a life raft. It was the first of a remarkable trilogy, followed by 2003's Mercury-nominated Cuckooland and 2007's Comicopera. With the help of Alfie and friends such as Eno, David Gilmour, Paul Weller, Roxy Music's Phil Manzanera and saxophonist Gilad Atzmon, he created the most wondrous music of his life. Then he gave up the alcohol that had given him the courage to make it.

"I think the recklessness that had fired me in the past began to dwindle," he explains. "Alcohol took me back to my reckless youth and the further away I was from real reckless youth, the more alcohol I needed just to get that level of chutzpah." So he quit. He hasn't made a record since.

While Wyatt poses for Q's photographer, I talk with Alfie. She discusses his new compilation ("If I did a Robert collection, it would be all the things that irritated everybody"), his politics ("He's a good communist; he doesn't underestimate people's intelligence") and his creative lull since Comicopera. "It's strange because I've never known him not to be fussing over a tune in his head. It's as if he's got it all out."

|

|

Does Wyatt think he'll ever make another album?

"No," he says. "I'm just amazed that at last I got records made that I can really live with, that don't make me wince."

Having played just one solo concert, 40 years ago, he thinks stage fright and logistics would make a Kate Bush-like concert resurrection even more unlikely. "It would be undoable," he shudders. "It's appalling, just the thought of it."

So Wyatt's career, apart from his occasional guest appearances, seems to be over. This is very sad for his fans, but less so for the man who never expected to achieve as much as he has.

"I can't believe my luck that with my attitude problem I nevertheless got all that done," he says, tugging his beard. "The extraordinary thing is that at the age where rock musicians are meant to die of a drug overdose I almost died." That was a trajectory he could've imagined. What he could not imagine was the life that he ended up living, wheelchair-bound. It was a "marathon" he couldn't think of enduring. "I'm a sprinter."

Dorian Lynskey

Portraits : Michael Clement

|