| |

|

|

No thing can stop him - Option #39 - July-August 1991 No thing can stop him - Option #39 - July-August 1991

fter three albums with the group, Wyatt departed because of their increasing seriousness. The formation of Matching Mole (a pun on the French for "soft machine," a name itself lifted from the book by William Burroughs) in 1971 revealed him to be a truly gifted lyricist and singer, as on "O Caroline," from their debut offering on CBS. Following a second Matching Mole LP, tragedy came in June of 1973. Wyatt found himself in critical condition in Stoke Mandeville Hospital, suffering from a broken spine after falling from a third floor window at a London party. LSD became the apocryphal culprit, but the truth was more mundane. Wyatt was trying to exit the party via a drainpipe when he fell because "of good old alcohol, the legal one." He would never walk again.

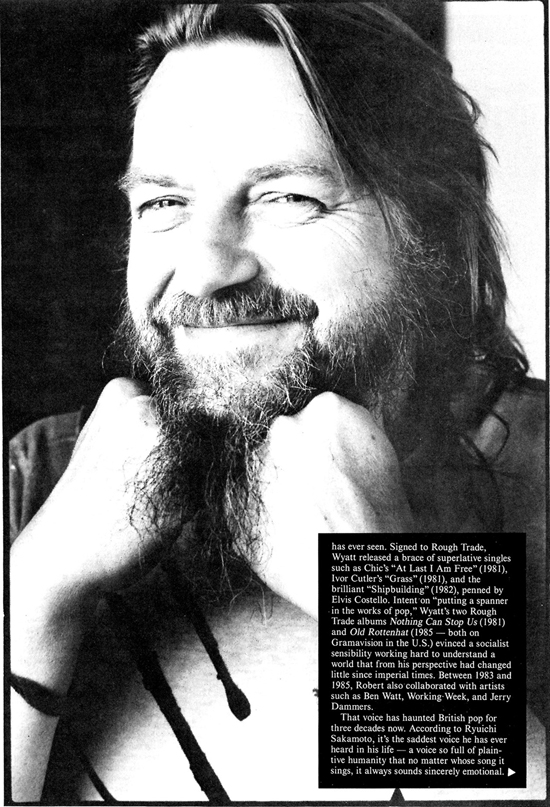

Six months in the hospital led Wyatt to produce his classic second solo LP Rock Bottom (1974), and with help from Pink Floyd his career was rejuvenated. His cover of the Monkees' "I'm a Believer" became a hit single that same year, and he later returned to live work with Henry Cow. If the late 70s saw Wyatt become more politically oriented, the early '80s saw him produce some of the finest independent pop Britain

So on Sakamoto's new album Beauty, Wyatt injects the Stones' "We Love You" with that trademark twist of melancholy. But it is a sound that also revels in celebration, in the sheer audacity of things.

|

These days Robert lives with his wife Alfie in the Lincoln village of Louth. His spacious 19th century home houses a grand piano, a drum kit, a home recording studio, a definitive jazz record collection, and a lot of books of the politically philosophical kind. In fact, his reading desk is as much a focal point as his beloved piano. Asked about the use of Music For Airports, on which he soloed with Brian Eno, for some of the steamy sex scenes in the film 9 1/2 Weeks, he chuckles. With no new album since Old Rottenhat, the appearance of "We Love You" with Sakamoto points to a low-key Wyatt, industriously working away in the background as others push themselves forward.

"I don't really use the word collaboration," he says. "I call it alternating dictatorships! Really, I work for other people or other people work for me. Specifically, the last thing I did was sing a song for a big band called Happy End. They brought the tape up from London and we recorded it in Sheffield. It was called 'World Upside Down' and I was very pleased to be asked. They are a big big band, around 20 people - bigger than the Count Basie Orchestra. I saw them a few years ago in London, probably at a miners' benefit," he recalls,before moving on to other works.

"Ryuichi Sakamoto is a really interesting composer. I like Beauty and I'm really into what he's doing next in New York with some hip-hop people. He's moved there now, you see. I really like the Youssou N'Dour track 'Diabaram,' and it's funny that, because it's more like the kind of track you'd expect to hear me on. 'We Love You' was sent to me with his guide vocal on it, and he just said replace it with my own. It was that simple."

|

ther recent work has been with Kip Hanrahan in the States and Chris & Cosey in Britain. "I did some music for a poem by Paul Haines which was put together by Kip Hanrahan. He does all kinds of projects and works on things simultaneously, so this hasn't seen the light of day yet. I chose the poem and put the music to it. Also Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti, who used to be in Throbbing Gristle. They now live in Norfolk and were just putting together some tapes and asked me to collaborate. It was the first time I heard my own voice being used with a sampler. I actually had a tape of me singing 'Autumn Leaves' and some other words, and Cosey shuffled them about into little fragments. Though it's basically her singing and. their music, it comes out feeling like me. They've got their own studio, are self-sufficient and do stuff. It was a true collaboration in that they did the work. I did the 'co,' they did the 'laboration,'" he laughs.

Wyatt self-effacingly admits to being able to do all his bits and pieces at home, where he can sing at his leisure and record at his pleasure. "I can go to a studio if I have to do more." For Old Rottenhat, his last proper album, the ten tracks were finalized in Acton and Brixton. He has been working up material for a new album for quite some time now. When ready this will be delivered to Rough Trade, a record company he's still loyal to because "they haven't got reams of paper saying you've got to do this, you've got to do that. They're absolutely straight and honest you know, which is such a nice feeling."

Working with Rough Trade is an intriguing juxtaposition of the old with the new, a post-punk enterprise which has only been around roughly half the length of time that Wyatt has been a professional artist. Wyatt contends that his musical taste had really been formed in the 1950s, but that his own abilities to make good music weren't developed until the 70s. "To me that was a strange, weird period. All sorts of things happened, but what I remember is hangin' around Victoria Station wondering if I missed the 10:50 back to West Dulwich and looking in the fridge and thinking sod, nothing in it again!"

Given the present fascination for all things 1960s, Wyatt's recollections of the era in which he first made his mark make for insightful comment. "For most of the '60s I was very hard-up. I spent the first half of it just struggling desperately, working in a forest, washing up, anything really. Then the music gradually evolved into various groups, and towards the end of it I was able to make a living. Eventually I became a drummer, but it wasn't by all means certain that that's what I'd become."

But there were flashes of rare experience, even if outside London the Soft Machine were booed off the stage on a regular basis. "What pulled us together musically was not audiences as such, but being on the road with the Hendrix trio in 1968. They were so nice to us. At the end of the tour Mitch Mitchell gave me this custom-built Maplewood drum kit. They knew we hadn't much money, but without being condescending they kind of just helped us along. They never tried to pull rank on you, they just wanted to encourage us by not saying anything about the duff bits in our set and helping us with the good bits. All three of them, Jimi, Noel, and Mitch."

The Soft Machine lineup of Kevin Ayers, Mike Ratledge, and Wyatt were matched up with the Jimi Hendrix Experience simply because they had the same management team of Chas Chandler and Mike Jeffries. Advised to get Donovan hitmaker Mickie Most to choose some commercial material for a debut single, the Softs responded with "we're only doin' our own stuff," so that was that. Their debut single "Love Makes Sweet Music," produced by Chandler, really didn't cut the mustard in an era of great pop tunes.

|

s to the years spent being the driving force behind one of England's classic psychedelic rock bands, Wyatt recalls Soft Machine's artistic development from an interesting perspective. "In terms of how we amplified our music we were a rock group, but what we heard in our heads wasn't pop music. We never looked to other groups for inspiration, in fact we were listening to Coltrane records. We got booed a lot in England at these dances where people were waiting for Jimmy James & the Vagabonds and instead got us - not a tune they recognized, just a row of stony faces; I thought the worst part of it was the break between numbers when there'd be this silence. So I suggested we link all our tunes up together so that the end of one was the beginning of the next. So the only time we stopped was when we left the stage, and that was how we developed the Soft Machine style of sustained continuous sets. Because of this brilliant compositional device, I never really had a clue what the audiences really thought of us.

"But we did get to make our debut album in New York at the end of the six-month tour of the States in '68. Now what was incredible about Jimi Hendrix was that he never got boring. You'd think seeing something each and every night after you played would make you want to go home, but not Hendrix. He was that good - all you wanted was more, even if it was the same. Another thing about him was that he was very professional and audience-conscious, if he was in front of a sophisticated bunch of New Yorkers, he would go every which way and try out all kinds of stuff - pure electronic music, even white noise. If he was in an aircraft hangar with a group of 14-year-old Texans, he would play the hits. Doing anything else would be going over their heads, and he saw there was nothing basically clever in doing that. In a sense he was a very old-fashioned entertainer who knew that people had paid money to see something, and he wanted to make sure they got it."

Working with Hendrix obviously sharpened Wyatt's perspectives on the so-called '60s revolution. What happened in America is viewed by him thusly: "During the '60s the black American civil rights thing had come to a head. And this had its roots in the Harlem renaissance of the 70s and the jazz scene of the late 1950s. That was taken up by radical whites who went forward with their anti-Vietnam War protests, but for me the central alternative thrust had already been there in the black American cultural thing. Charlie Mingus, Dizzy Gillespie, Max Roach were part of the central explosion. The rest was an offshoot of a cultural revolution I'd already experienced.

|

"With regard to drugs, straight dope/hash had always been part of black American culture. The difference between white hippie culture and black jazz culture was not there, but in the fact that hippie culture was a deliberate, we 're-not-having-anything-to-do thing, a deliberate drop-out. The black American experience was fall-out. They didn't have an establishment to drop out of. They weren't allowed in anyway."

Wyatt is aware that you can't generalize and that a lot of people don't qualify, but what he's saying makes sense. "What we are really talking about here is a cultural celebration amongst people who were already living in two or three of the richest countries in the world anyway. It was really about the young and relatively affluent exploring new cultural ideas. And that was very nice, but what would be silly would be to think that changed the fundamental structures. The notion was that we won't even try anymore, we'll have a good time in our own way and somehow we'll change the fabric of society. But that completely underestimated the plasticity and intelligence of the political, military and banking establishment of our economies and countries and how they're run. It was just children playing on the lawn while the grown-ups make the big decisions in their kitchen."

Conversing with Robert Wyatt, it is not long before the subject turns to politics, a force that seems to drive his very being. "I would say that almost by the mid-1970s I could hardly be called a musician. I felt like I've turned into one of those sandwich board nutters who go around saying the end is nigh. But as I happen to be a musician, it comes out through music. It's really what I think about, music happens, it's what I do. But the core of what I'm thinking is political."

|

mere mention of any social or political phenomenon will launch Wyatt into a broadside which has all the incisive quality of distilled truth. "I haven't got a great knowledge of all the world, but there are particular things I think about which are as frightening now as they've ever been. It's funny to hear people talking about, it's post-cold war this and post-history that - post-ideology and post-every-bloody-thing. Most people in the world don't have access to free running water, most people don't have access to proper literacy. So what's that supposed to be. And it doesn't get sorted out.

"I have to admit I'm very narrow-minded, blinkered like a horse. I'm not a broad liberal thinker, but pursue certain things endlessly. And the people who put it articulately are writers like Susan George and Noam Chomsky. She talks about the problem, he talks about how the problem is maintained. She basically says that rich countries have developed purely at the expense of the poorer ones. And I know a lot of people know this, but the facts have been sort of marginalized.

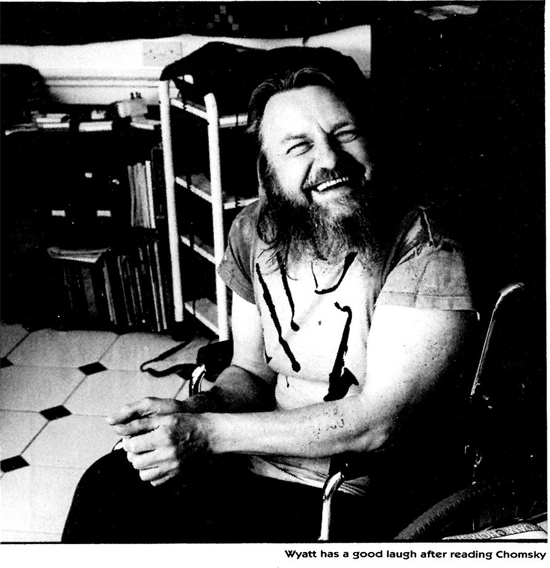

"Chomsky is a hero of mine, he saved my life. He's an American linguistics scholar who writes about the complete moral collapse of the western intellectual world. Now I get emotionally heated and I'm what you call a half-wit (laughs) - I've got half of a wit which functions very well, and another half which is not so good. But he's got a whole wit." Chomsky's thinking and his views about distorted language are written all over Old Rottenhat, particularly such songs as "The United States of Amnesia" and "Speechless." To his way of thinking, what Wyatt sees on television and in the newspapers is only a version of the truth, wrapped up in a language that is acceptable to the west.

Wyatt tries to keep abreast of musical developments almost as fervently as he follows politics. Though he doesn't see the recent New Age or acid house movements as being significant agents for change, he's interested in the rap situation in America. "This is how a lot of black Americans have found or come to terms with the fact that their revolution to be in control of their lives is a permanently put off fantasy! And that's because they're outnumbered. So rap is how to develop a kind of sense of 'we're gonna have a life,' 'we're gonna have a culture,' 'we're gonna do what we can,' but in a permanent state of siege."

Once Wyatt gets his teeth into a topic he finds it hard to let go, so a good 40 minutes is passed by his delving into the shortcomings of British politics, the Liberal/Tory power axis, and the ebb and flow that characterizes the unchanging face of the British power elite. He even has his doubts about the Labour Party, which holds views most closely associated with his own. "Still, I think the Labour movement is full of heroism and a tremendous energy. I admire Jerry Dammers, who was in the end responsible for the Mandela concert, Billy Bragg, the Communards, and all those who were involved in Red Wedge. If I vote Labour it will be out of loyalty to them and the local people here who may not know anything about access to power but are loyal to their party."

So Wyatt is not all doom and gloom. Though he sees world music and third world film as something functioning at the behest of first world technology, he's still inspired by exotic musical mixtures. "A lot of my musical inspiration comes from people whose ancestors come from other parts of the world. It means that there's a built-in possible future in our culture that hasn't yet reached the political establishment."

Gramavision, 260 W. Broadway, NY, NY 10013

|