| |

|

|

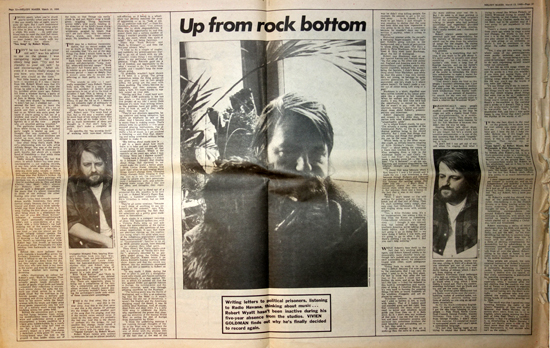

Up from rock bottom - Melody Maker - March 15,

1980 Up from rock bottom - Melody Maker - March 15,

1980

JOKING apart, when you're drunk you're terrific; when you're drunk I like you mostly late at night, you're quite all right. But I can't understand the different you in the morning when it's time to play at being human for a while. We smile... So until your blood runs to meet the next full moon, your madness fits nicely with my own — your lunacy fits neatly with my own. We're not alone." —

"Sea Song" by Robert Wyatt.

« Don’t be too hard on your old self », was his advice to me on the phone. I was castigating myself for some idiocy long past. « Try and be friendly to your old self, » he said encouragingly. « After all, even if it seems really stupid to you now, you were doing the best you could at the time. »

This little homily could well have been – sounded as if it was – learnt from life. Robert Wyatt says that it’s only recently he’s begun to miss the things he used to be able to do before his accident seven years ago. Robert fell from a window during a party at Lady June’s flat in a mansion block of flats in Maida Vale.

« I was very drunk, » he remembers. « I didn’t fall out, I climbed out… it seems the best way to leave the party at the time. Yes, I did a lot of punch and then a bottle of whisky and so on. Which was quite good, because if you’re going to fall out of a window and you’re drunk, it doesn’t hurt quite so much. Soldiers and bullfighters do it all the time… people who are smashed getting smashed. »

The particular window Robert fell from while trying to evade a typical party tangle is sealed up now. I thought that was symbolic, until I found out that all those windows are sealed up now ; some painter’s mistake. Perhaps is still symbolic.

One other thing that’s stuck : Robert’s relationship with his wife, artist Alfreda Benge. She was at the party, and it’s a sticky web of emotions – guilt, loyalty, but above all, a simple bond of friendship – that welds them together as a creative unit.

Oddly enough, during the past five years, in which robert has been passive/receptive – not making records, at any rate, while absorbing information from all over the place like a deep-sea diver gulps oxygen – Alfie’s own visual output has been declining. Perhaps now that Robert’s broken the five-years silence, Alfie’s paintings will increase, too.

|

As a music/visuals team, they're matched only by Don and Moki Cherry; like Moki, Alfie's sleeves for Robert's two solo albums provide such a deep-pile context for the music that it's almost impossible to think of one without the other floating into your mind.

Robert's lyrics tend towards surreal dream worlds. Sometimes they seem surreal simply because they're so colloquial and direct you'd think nobody would sing those kinds of words in a song. Calling the first album you make after being stuck in a wheelchair for the rest of your life "Rock Bottom" indicates a surreal/straightforward wit that's awesomely matched by Alfie's eye: a cross-section of a seascape, with a little Robert's top half popping out of the water's surface, waving a big bunch of balloons in one hand — you can almost see the bright lollipop colours speckle the sky, though it's a grey and white pencil drawing — but beneath the water line, there's no matching pair of little Robert legs. Just fronds, or tentacles of passing octopi. Presumably it's Alfie bending over backwards on that tiny island.

Behind her, more balloons float gaily towards a boatpuffing across the horizon. Someone standing on the deck is bound to see the balloons and want to grab one down from the sky, but they might never know that the little man who held them is out there in the water; and even he doesn't seem to know whether he's waving or drowning.

Alfie's illustrations go colour for Robert's next, "Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard". Two curious animals — actually people, heads shrouded m masks of gaudy ritual birds and beasts — examine their reflections in mirrors. Each mirror shows the same red sun, each sun sliced across by a razor-blade cloud. But the bird-man in the fairisle jumper sees a solitary gull swooping and diving across the green field in his mirror, while the beast-woman with the beads and hippy print dress gazes impassively into her mirror, at a solitary small woman figure trudging across her green field.

Behind the uncommon pair, a washing-line hangs between trees, stringing miscellaneous items of household ware and underwear across a gypsy encampment: a brown cauldron on a tripod goes hubble-bubble by a comfy armchair, a book lying half read on the flat earth beside it. A green gnome's teapot on a grey tree-stump, a deckchair, a little green TV, even an ironing-board near the hole in the ground. A blue ladder sticks out of the hole, so that Things can easily climb in and out; there's even a small green wiggling Thing squirming across Alfie's wild world, heading in the direction of the bird's house slung from another tree. Ideal Home in the wilderness, peopled by beasts that can't see each other, only themselves. What's worse, only their inmost souls. No breathers for commercials.

THIS may be a dubious recommendation, but no record makes me cry as much as "Rock Bottom". Robert concedes that "it's one of the only things I've done I would listen to myself. It's one of the only records of mine I've got, I think."

Each track reminds me of Robert's musical self-description: "Long, doleful, when-will-this-end songs." "Rock Bottom's" full frontal pain — at least as intense as any Lennon in his Primal Scream period - sears so deeply that it doesn't seem idle to assume he's referring at least partly to his accident.

"This sounds so silly - I can't really remember," says Robert. "Somebody said, 'Oh, this is a cry of pain from the accident.' It doesn't sound appropriate to me at all to the kind of accident I had. This is taking it too far. You make records instead of saying things. It's up to anybody who listens to put the lid on it. I reserve the old romantic right of ambiguity in art, 19th century though it may sound."

About "Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard", Robert says: "I'm more fond of that, but in the way a mother might be more fond of her mongol child than the one with all its limbs intact. It's got so much investment of ideas and thought in it that don't hang together, don't make a complete record..."

He specifies the "fan worship thrill" of working with now-dead African trumpeter Mongezi Feza, hearing Mongezi's rhythms hook into Gary Windo's horns, "jazz, not jazz-influenced." Bill McCormick and Laurie Allan were the bass-and-drums-respectively rhythm slice, and Robert was on piano - "I got a vague inkling of how enjoyable it must be to be a pianist in a jazz group."

Both "Rock Bottom" and "Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard" are deleted by Virgin Records, heaven only knows why. There are, apparently, plans to bring out a compilation of the two; why a compilation and not a double album re-issue I equally cannot imagine. I certainly wouldn't fancy wielding the anthologist's knife over either of these immaculate assemblages.

"THIS is the first verse, this is the first verse... and this is the first verse. And this is the first verse — and this is the chorus. Or perhaps it's the bridge. Or just another part of the song that I'm singing. And this is the second verse, second verse. It could be the last verse. It's probably the last one. And this is the chorus or perhaps it's the bridge. Or just another key change. Never mind; it just means I've lost faith in this song, 'cos it won't help me reach you... — "Signed Curtain", by Robert Wyatt.

Robert Wyatt listens with interest to everyone ; he can be almost painfully self-effacing, as if being in a wheel-chair had entirely removed the onus of aggression — as in, "look at me, I'm an assertive rock star" — from his shoulders. Robert says: "I've always been one to shirk responsibilities if there was the opportunity to, and this meant there was a certain number of things I couldn't possibly be expected to do any more, which was quite a relief." He's not being facetious.

There was "Rock Bottom" and "Ruth Is Stranger" - and then the five-year silence. Why?

"I tried to do a couple of singles, and suddenly my preoccupations started to go out of synch with my job. I couldn't relate things I was thinking about to my particular mode of expression. Virgin Records gave me a lot of freedom and opportunity to do what I wanted to do. I've never been prolific, and I couldn't keep the momentum going.

"It probably wouldn't have shown if I'd been in a group. The group momentum keeps the thing going—at any given point, one or two people within the group are the ones with ideas, pushing. The others become interpreters, and then someone else takes a turn. It's much harder to sustain output on your own.

"Having said that, I must have written about 2,000 postcards in the last four years — the most exciting creative project of my life! I wrote them because it's nicer than writing letters. so the postmen have got pretty pictures to look at, and if they really want, they can read it.

"They're not absolute opposites, being creative and being receptive, but there's an emphasis on one or the other. And I became more interested in music than in making music. That's always been my problem - I've never enjoyed playing instruments, I've always enjoyed listening to records. I'm really a fan of music, so I get involved in listening — and, from that, observing and being interested without being obliged to make it.

"My feeling about music now is... I get in a panic about how much there is to hear and not enough time, so it's going to get wasted, all that unappreciated beauty. Which is the opposite of ten years ago, when I was thinking: "How can I express myself?'

"Going back in the studio — I didn't do it because I thought that singing about things that mattered to me would make the world a better place. I think Linton Kwesi Johnson was quite right when he said singing about things doesn't change them. Changing things changes them. Singing is singing. Just as in art, I'm interested in songs by people who have preoccupations I sympathise with, and acknowledging some songs that I like and the ideas and thoughts they represent."

The result so far is three out of a projected five 45s, possibly to be sold in a set — Robert Wyatt's Paper Bag, perhaps, a humbler collection than PiL's 12-inches in metal, but no less cogent.

They're all cover versions, "because I can't think of anything to say coherently at the moment," says Robert, modestly ignoring the fact that his selections are a pretty good statement in themselves.

Each single is a compact two-step of ideas. The Spanish-spoken one, with a Violetta Parra song on one side about the extermination of the native Chilean Indians, askks questions of American imperialism. It says that there are elections coming up, the implication being: what's the point when most of the indigenous population's already been exterminated? The flip's a version of "Guantanamera", familiar to us all as MOR elevator muzak, here restored to its original, fiery rebel spirit.

Then there's the Stalin single-one side is a version of "Stalin Isn't Stallin'", originally recorded by an acapella gospel group, the Golden Gate Jubilee Quartet. Robert heard it on Alexis Korner's Sunday morning radio show. Alexis said that the record was deleted, like the sentiments expressed in it, and sent a cassette to Robert on request.

"It was made, I think, during the war or after it, and it's a straightforward rally-round, anti-fascist solidarity internationally in a war against Hitler, in which it's pointed out that the war against Hitler and against fascism in Europe, the turning-point and the major victories, were won through amazing sacrifices by the Russians.

"The turning-point was the Battle of Stalingrad, and — this is an embarrasing fact for the West — it wasn't bombing the shit out of Hiroshima, it wasn't the English and the Americans charging round the desert, it was 20 million dead Russians. And, of course, dead Poles and dead Jews. It's a jolly little song to celebrate Joe Stalin, who represented the power that changed the direction of the Second World War, so saving the rest of Europe from domination by Hitler...

"I think the underlying exercise I see running through thoughts of Stalin in the West now is to replace the idea of the all-time 20th century monster of Hitler with the all-time 20th century monster of Stalin. On account of the fact that at the end of the

|

|

war he didn't stop killing people, for example. He seemed to get a bit carried away... to be honest, I don't want to get heavy. I just thought it was amusing to realise that the song had been done and how impossible it was going to be to find a composer, because he wouldn't dare say he'd written it anyway, when it comes to royalties."

Historical interest aside, the record's swinging finger-snapper, with fourpart Roberts going ooh-ooh in the background, and a touch of percussion to spank along the pace. The flip's a poem by Peter Blackman, father of the Steel & Skin steel band Blackman, about the fall of Stalingrad.

Robert saw Blackman read at an Art Against Racism and Fascism show. "As that song on the other side points out, England and America were for five extraordinary and unlikely years anti-fascist countries, because they weren't being the fascists. I didn't know anything about Peter Blackman, and when he read this poem I was very moved. He's not young, he belongs to quite another generation, the Thirties Left movement, and he's stuck to it where others haven't. He hasn't made a career out of either being Left wing or a poet."

Blackman is a short, dignified man who carries himself in his casual polo-neck like a general in full honours. When he walked into the recording studio, it was the first time he'd had the opportunity to record his work. But he wasn't in any rush. He was cautious, wanting to know and under-stand more about Robert's preoccupations and intentions.

Robert displayed great deference and respect to the older man, who recites with what Robert describes as "unapologetic pride".

As to where Robert stands, he says: "I'm actually a caring member of the Communist Party, so I'm in a paradoxical position being in the record industry. But I think that things that are serious and things that people enjoy can be the same thing ."

Which leads on to the other recorded single, an initially bizarre coupling of Billie Holiday's classic, "Strange Fruit" — about seeing the corpse of a black man lynched by the Ku Klux Klan swinging from a tree in the American South — and Chic's "At Last I Am Free". As when Robert made a parallel cover hit — the Monkees' "I'm A Believer" — all the ambiguities and tensions disguised by the original straight pop format stand naked.

I chose that song because when I

first heard it I was a bit pissed and it made me cry. I was interested in that, because though Rodgers and Edwards are acknowledged songwriters, they're not famous for writing songs that make you cry... I don't think it necessarily moves me the way it moved them when they were writing it. But anyway, there was a bonus in Ihc fact that it was in my range."

Which is... ?

"Well, I don't know — I'm still waiting for puberty and my voice to break and all that sort of thing. Then I'll start covering men's songs, that men sing. Just technically, I find myself singing along more with women singers.

"Yes, a Billie Holiday song. It's a bit inappropriate, like asking a Jew to sing from the Koran or something. Cross-cultural references, it's not my song... I thought it was relevant now, but instead of talking about Southern America, we're talking about South Africa. And I thought, we're just going to go on doing this — we were doing it before I was born, and it's going to go on after I die, and there's nothing I can do about it. But you can't help noticing."

While Robert's fans thrill to the fact that he's working publicly again, and Robert himself seems to be measurably more cheerful lately (although he's racked with nerves about each succeeding move), his pleasure's tinged with other, more ambiguous emotions.

"Going back to work is in some ways a defeat. Because I've now come to the conclusion that I can only do what I used to do in the first place. I'd like to think that after the last four or five years I could now see further, do more, and so on. But this isn't the case — I find I'm reduced to this built-in introspection and narcissism of being A Creative Person, and it's very hard to harness the amazing things I've seen or heard. Suddenly all the Windows disappear and are replaced by mirrors.

"Everyone believes in something, and I used to believe in Art, in truth with beauty. That if it looked good and sounded good and felt right, then that contained the main truth you need to know and intuition would guide you from then on. If it feels good, do it. I don't seen any evidence of that now. I can see that the cruellest and most repressive peoples and societies can sometimes produce the most beautiful and astounding art — in fact, they need to.

"If another analogy is that art is make-up then the more of it you need the more dubious your real life is. But I do need to at least pretend to believe in something. And religion's out of the question. I've found that talking to people who had political knowledge and experience provided the stimulus that I'd been missing, that I really needed, and I clutched on to that."

Robert always seems to assume Personal guilt and responsibility for the history of Western Colonialism, which can be seen from his selection of songs for the singles. He claims that the aesthetic — is it a nice tune? — comes before the moral in his selection process.

"Art to me is everything that isn't true, if you want to be glib about it. It's quite useful to actually care about something... but I do come, on my mother's side, from a long line of Kentish fascists, and on my father's side I come from a long Une of missionaries going out to various parts of the world to intimidate the locals into submission to make it easier for Western European colonial expansion. Although they'd deny it.

"That doesn't make me kind or like people I wouldn't otherwise like. I just feel angry that I was born a receiver of stolen goods. My immediate parents were breakaways from family tradition... but no amount of masochistic search for my own evil cultural roots would make me actually want to have a relative like Woodrow Wyatt."

PARADOXICALLY, many people think one of Robert's greatest musical contributions is the way he sings; not with a classic Good Voice, just straightforwardly, in a middle-class English accent. This, despite the fact that one of the main reasons he left the Soft Machine is because they didn't like the way he sang.

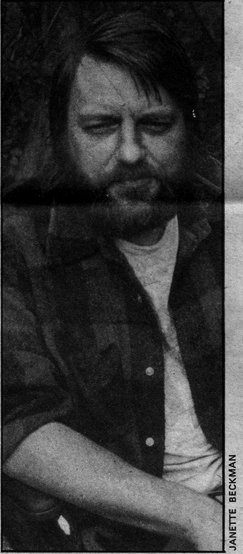

Hearing Robert talk about drumming — obviously, he can't use a full kit any longer, but he's a sturdy and sensitive percussionist — is one of the few moments that the word "tragedy" pops into your head while you're talking to him.

"I don't feel I can get out of myself when I'm singing. And what I remember about playing music was the way, sitting in front of a drum kit, you somehow got out of your mad skin into the outside world — a wonderful feeling of release which I don't get from singing at all."

Robert's Everyman vocal technique — I'm just an ordinary bloke, why am I so sad? — he puts down to this: "I go blank when I sing, which I think makes it sound sad. That's my sincere-sounding technique. Just go blank and try and get the notes right."

He has evolved some flamboyant but not flashy vocal styles over the years — babbling rushes of overlaid noise, colloquial speech patterns eliding over lines of melody so you sing an up-and-down incantation.

As for the much-celebrated Englishness: "It wasn't patriotic in any way. I got the idea from listening to other people — Pink Floyd, Kevin Coyne, Noel Coward, George Formby, Stanley Holloway, Vera Lynn — but, apart from George Formby, I didn't relate to their material. I'd committed myself to syncopated music, and I don't speak a syncopated language.

"It's just that hearing tapes of me trying to sound like Steve Marriott trying to sound like Wilson Pickett, or Stevie Winwood trying to sound like Ray Charles, or Joe Cocker trying to sound like Ray Charles, made me realise there had to be another way if I was going to get anywhere in this business."

There's a classic John Peel session from years ago where he sings a song and Changes the words to say how nice it is at the BBC, where they let you play almost as long and as loud as a jazz group or an orchestra on Radio 3, and he continues to sing about the coffee machine in the hall...

"Yes, I also got into writing words where some of my preoccupations were purely technical, and they'd come out as human-being-not-interested-in-technique things, and others to do with expressing myself would come out calculated.

"I got fed up with songs where the main accents would make you emphasise the words in a way you wouldn't if you were just saying them, and I got interested in the technique of writing songs where the melody line fits the way you'd say the words if you were just talking.

"I'd say things you'd say in conversation, not even serious conversation, just things you'd say to make a noise. And that meant singing about things that were true as far as I understood it. And if you're muddled, the only things you're certain are true are that there's a tea-machine in the corridor and it works or it doesn't. This is true, it's not wishy-washy bullshit. It may be low-profile, but it's true. Then I abandoned that, and later I was quite happy to sing things that didn't match the rhythm of the words at all."

"I'M the one face down in the mud on the ground, I'll be stuck here for ever unless you come over and kick me... I'm the best of all you have got. I beat the lot. I take the cake. Believe me, if it's tough you want, then it's tough you've got. I mean, if this is only a question of toughness. Then survive me, or deflate me, pronto..."

"Team Spirit", by Robert Wyatt, Bill McCormick & Phil Manzanera.

The house, bought for the Wyatts by friends after Robert's fall, is in a finely-preserved street in a residential, riverside area of West London. The Wyatts live on the ground floor. It's a circumscribed world for Robert in his wheelchair, and so it has to be a complete world.

|

|

The flat's full of rich, glowing colours, the layout and design catering for the fact that Robert needs effortless access to as much information as possible.

I once suggested that Robert should get himself an invalid car, and up his independence and mobility a hundred fold. Robert laughed and said No — he'd just go off in a daydream, and be bound to crash. Alfie merely commented: "No, not Robert, he's a born passenger..."

So Robert's world has shrunk from that of the globe-trotting rock'n'roller, free-forming it on the French Riviera or in Ibiza, touring across the States supporting Jimi Hendrix ("I thought he was a real gentleman").

Interesting correspondence lies around Robert's desk. Letters from Africans in detention, with whom he's carried on lengthy correspondences which started out as sending a Christmas card and blossomed.

Robert maintains a series of letter exchanges from his desk, and spends a great deal of time listening to the radio; not just the BBC, for his dialtwiddling has led him to uncover long-range frequencies that keep him in touch with far global corners. It's a form of obvious compensation for immobility, but by subscribing to an enormous amount of magazines and literature and listening to people talk from all over the planet, Robert, sitting in his chair at home, is probably more in touch than he ever was in his mobile existence.

When people are around, the only external indication of Robert's frustration is the way the former drummer is constantly drumming — cigarette packs, lighters, anything that's lying around is fiddled with and tapped, so that every conversation is punctuated by non-stop syncopation.

"I wanted to get out of this place, especially when I realised after the last election that the country was just full of Tories — I wanted to separate myself, and I couldn't do it physically, so I started tuning into the short wave radio... to anyone who was considered the enemy, with immediate strong bonds of sympathy pouring out to them.

"The result was that I spend my time hovering between the radio of the Islamic Republic of Iran and Radio Moscow. And Radio Havana, on 41 metres short wave, from ten to 11 in English, which means missing the first part of John Peel. That's a sacrifice, seriously — but I'm prepared to make it, so entertaining is Radio Havana. I found out there's more to life on the short wave than the enemy, and it's very Eurocentric to call anyone who isn't us the enemy."

Vivien Goldman

Photos: Janette Belkman

|